Out of Egypt: The Big Six

Sidebar to: Egypt’s Chief Archaeologist Defends His Rights (and Wrongs)042

One of Zahi Hawass’s biggest campaigns as Egypt’s head of antiquities has been to secure the return of many of Egypt’s most prized objects from museums throughout the world—sometimes as a loan but more often as a full return to Egyptian ownership. As Hawass explained to BAR “I’m not against every [Egyptian] artifact in every museum. But anything that I do have evidence that they are stolen from Egypt should be back.” By his count he has had more than 5,000 such artifacts returned to Egypt. Six high-profile objects were still at the center of his efforts when this interview was taped. These antiquities were discovered in Egypt long ago and removed, and Hawass believes they should be returned. The institutions that currently hold them, however, are defending their claims of rightful ownership in the face of mounting media attention.

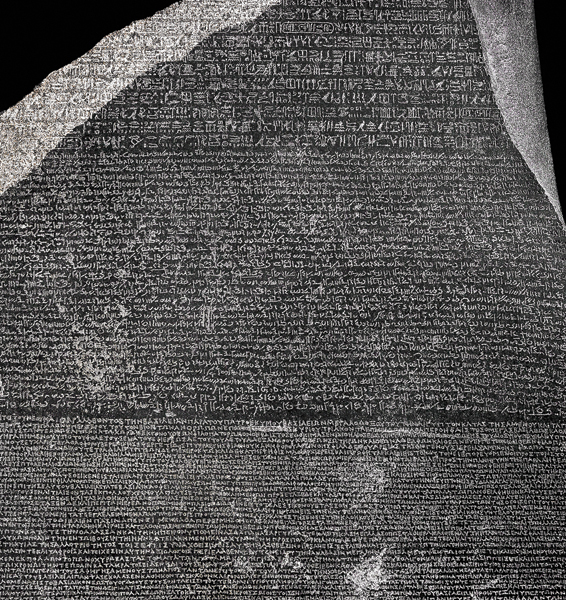

The Rosetta Stone

British Museum, London, England

In 1799, during Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, the Rosetta Stone was unearthed by workmen constructing a fort near the town of Rashid (Rosetta), and the French officer in charge of the project realized the stone’s potential importance because it was part of a stela inscribed in three different scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic (Egyptian cursive) and Greek. After the British defeated the French in Egypt in 1801, the almost 4-foot-tall stone came into British possession and was transported to London, where it has been on display at the British Museum since 1802. It was not until 20 years later, however, that the text was fully understood, when Jean-Francois Champollion became the first to crack the code of hieroglyphic by comparing the royal names in the oval hieroglyphic cartouches to the known names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra in the Greek portion. Once deciphered, the stone’s inscriptions revealed a decree from Memphis in 196 B.C.E. to commemorate the first anniversary of Ptolemy V’s coronation.

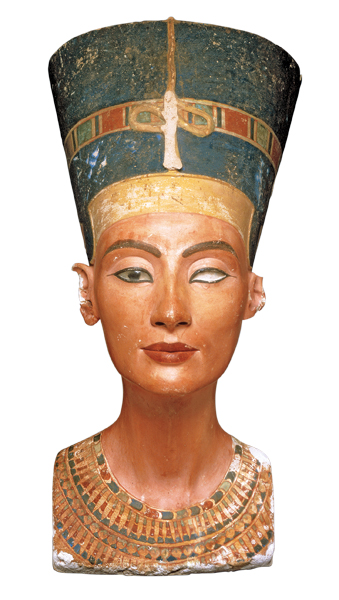

The Bust of Nefertiti

Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany

One of the world’s most recognizable ancient Egyptian artifacts, the bust of Queen Nefertiti was discovered in 1912 by a German-led excavation at el-Amarna in Middle Egypt. The beautifully carved and painted 20-inch limestone and plaster head of Pharaoh Akhenaten’s principal wife was uncovered in the workshop of the 14th-century B.C.E. sculptor Thutmose. Recent CT scans of the sculpture, which scholars date to 1345 B.C.E., revealed a more aged, wrinkled face carved into the limestone core beneath the smooth layers of painted stucco on the surface. The bust was shipped to Berlin in 1913 after the German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt and Egyptian officials divided up the excavation’s finds between the two countries. Despite the signed documents from the agreement, Hawass claims that Borchardt misled Egyptian officials about the bust’s beauty and importance, so he is entitled to claim it back.

The Zodiac of Dendera

Musèe du Louvre, Paris, France

This bas-relief of a zodiac that maps the stars was carved for the ceiling of the pronaos (portico) of a chapel dedicated to Osiris in the Hathor temple at Dendera, located on the west bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt, just a few miles north of ancient Thebes. The circular shape is unique in ancient Egypt, where rectangular zodiacs were typical. Now dated to 50 C.E., the relief was correctly identified by Jean-Francois Champollion as a product of the Greco-Roman period, while many of his contemporaries believed it to be much older. The disc is supported at four 043corners by female figures with anthropomorphic falcon-headed figures kneeling between them. Thirty-six spirits form an outer ring to represent the 360 days of the Egyptian year. On the inside of the circle, constellations and signs of the zodiac (Taurus, Scorpio, Aquarius, etc.) are represented in a mix of Egyptian iconography and more-familiar Greek symbols. An engraving of the zodiac was published in 1802 by Vivant Denon, based on drawings he did during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. The removal of the zodiac was begun in 1820 by a commissioned mason and in 1822 it was installed at the Royal Library in Paris.

Statue of Hemiunu

Roemer-und Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim, Germany

The Great Pyramid at Giza is one of ancient Egypt’s longest-enduring symbols, and now the man who oversaw its construction is getting a lot of attention—or at least his statue is. This 26th-century B.C.E. limestone sculpture of a seated Hemiunu, nephew and vizier of Pharaoh Khufu, was once painted. An inscription on the base identifies him by several titles, including member of the elite and Overseer of All Construction Projects of the King—the most famous of which was the Great Pyramid. The fleshy architect is depicted in great detail, wearing only a loincloth, with the face largely reconstructed. In April 2010 the German museum announced that it would loan the sculpture to Egypt for the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, then scheduled for 2013. The loan agreement provides for the statue’s return to Germany.

Bust of Ankhhaf

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts

Much like his predecessor Hemiunu, the architect Ankhhaf was a member of Egypt’s royal family and vizier to the pharaoh (Khafre, 26th century B.C.E.). Ankhhaf may have been involved in the construction of the second pyramid at Giza or possibly of the Sphinx. This limestone and painted plaster bust—considered one of ancient Egypt’s most realistic, unidealized portraits—was discovered in a small chapel inside Ankhhaf’s tomb. Votive pottery vessels lay nearby, suggesting that the sculpture, which sat on a pedestal, was the focus of a funerary cult in antiquity. The 1920s tomb expedition that discovered the bust was funded jointly by the Museum of Fine Arts and Harvard University, and the piece was assigned to the museum’s collection as a sign of Egypt’s thanks for the expedition’s work.

Statue of Ramesses II

Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy

This seated sculpture of Pharaoh Ramesses II is one of the highlights of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, which houses the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities outside of Egypt. The diorite portrait of Egypt’s most famous pharaoh, often thought to be the pharaoh during Israel’s slavery in Egypt, dates to the 13th century B.C.E., the time of the 19th Dynasty. Breaking from royal tradition, the king is portrayed in his war helmet, a long draped robe and sandals, grasping a scepter. His nose is unusually large, especially compared to his small mouth and recessive chin. Next to the king’s legs are smaller figures of Queen Nefertari and Ramesses’s beloved son Amunherkhepeshef, while nine bows inscribed beneath the king’s feet symbolize enemy tribes. Depictions of an Asiatic and a Nubian on the sculpture’s base represent Ramesses’s dominion over Egypt and all its possessions.