For the ancient Berbers who traveled across the parched desert on camels, the fertile oasis of Amun Siwa was a paradise; for modern travelers, it’s a trip back in time.

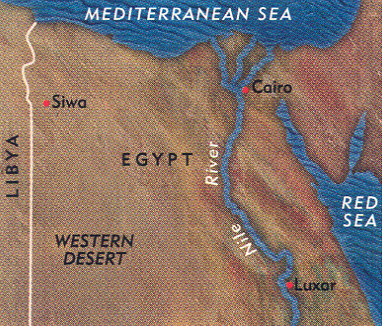

Sixty-five miles from the Libyan border, in Egypt’s barren Sahara desert, Siwa lies in a fertile depression about 60 feet below sea level. It is surrounded by enormous dunes, shaped like pyramids or flat-topped plateaus, that seem to stretch into the sky. Approaching the Siwa oasis on the road from Cairo, we see trees and shrubs begin to dot the landscape; then, suddenly, Gebel el-Mawta, the Mountain of Death, appears like an ominous stony guardian over the desert sand.

For centuries, Gebel el-Mawta was ancient Siwa’s necropolis. The mountain’s broad slopes and terraces are pockmarked with tombs—including the Tomb of Amun, which dates to Egypt’s 26th Dynasty (664–525 B.C.)a and is named for the chief god in the Egyptian pantheon, with whom the oasis was long associated. Gebel el-Mawta’s largest tomb, the Tomb of Niper-pathot, a prophet of Osiris, also dates to the 26th Dynasty. The Mountain of Death continued to serve as a burial ground for another millennium, through the Ptolemaic period (305–30 B.C.) and the Roman period (30 B.C.–395 A.D.). The third-century A.D. Tomb of Si-Amun, for example, is a well-preserved Roman crypt, consisting of a courtyard that leads to a narrow burial chamber decorated with funeral scenes: images of Si-Amun with his son, the god Osiris in his shrine, falcons, vultures, stars, birds and the Egyptian goddess Nut standing in front of a sycamore tree. Although many of Gebel el-Mawta’s tombs have been excavated, most can only be glimpsed through tiny, narrow entryways, but the bone shards and skeletal remains that are scattered across the mountain offer grisly hints of what lies within.

The most famous site in Siwa (even in antiquity) is the sixth-century B.C. Temple of Amun. The temple’s mudbrick ruins lie within a medieval Arabic village named Agormi, meaning “High Walls.” The village was abandoned in the 13th century A.D. and never reoccupied. A minaret from one of Agormi’s ancient mosques still pierces the horizon.

According to ancient sources, the Temple of Amun was the home of an oracle, visited by kings and emperors in search of wisdom. Herodotus (c. 484–425 B.C.) writes that the founder of the oracle was a princess from Thebes who was abducted by Phoenicians and sold to Libya. When the Persians occupied Egypt in the sixth century B.C., their emperor, Cambyses II (529–522 B.C.), sent an army to destroy the temple and its oracle, but his troops never arrived. Herodotus tells us that the Ammonians—Siwa’s ancient inhabitants, devotees of the god Amun—reported that Cambyses’s army perished when a terrible south wind buried his soldiers under “heaps of sand.”

Alexander the Great visited the temple in 331 B.C. to confirm his divinity as the son of Amun (whom the Greeks identified with Zeus). Although no one knows what the oracle said, Alexander indicated in a letter to his mother that he was pleased with its message.

In the sixth century A.D. the Byzantine emperor Justinian closed the temple as part of his effort to end paganism, and much of the building was later destroyed by Berber invaders. But the temple has now been partially restored; visitors can wander through the crumbling chambers, view scraps of ancient writing on the walls and peer into the narrow passageway through which the oracle spoke.

Ancient Siwa was also the site of several luxurious hot springs. Cleopatra is said to have bathed in the Spring of the Sun when she traveled to the oasis in first century A.D., and ancient brides would frequently visit the spring at Fantas (commonly known as Fantasy Island) on the eve of their weddings.

In the Medieval period (c. 1000–1500 A.D.), Siwa served as an important stopover on the caravan route from northwest Africa to the Islamic holy city of Mecca. In 1203 A.D. the area’s Berber population founded its own mountaintop settlement at the oasis, called Shali. The Berber settlement’s strange, arresting ruins still overlook the fertile oasis today.

Shali was originally a dense maze of buildings winding around the natural curve of the mountain. To conserve space, most of the city’s structures were built upward and outward from the mountainside. Each building was constructed out of local mudbrick and reinforced with palm tree trunks. The Siwan mudbricks, unfortunately, contain a high percentage of salt that dissolves away, crumbling the mudbricks during rain storms. In 1926, an unusually heavy three-day rain seriously damaged the town. Other storms in this century have continued to “melt” the medieval city’s walls. Many buildings have collapsed entirely, while others—reduced to the surreal formations seen today—are still inhabited. Locally, the ruins are often referred to as the “Melted City.”

Modern Siwa shelters a small but thriving Berber population of about 18,000 people, who speak their own Arabic dialect (Siwa). Many dress in traditional Berber costumes and cling to ancient Berber customs, including the strict separation of the sexes. Most residents of the oasis support themselves by cultivating olive trees and date palms. Since 1986, however, when a new road was built connecting Siwa with the Nile Valley, tourism has become an important source of the inhabitants’ income.

For the adventurous traveler, Siwa is captivating. Dark-eyed, berobed, veiled women. Young brides in wedding dresses elaborately decorated with pharaonic images. Colorful markets arranged with fruits, hand-woven baskets, wool rugs and fired pottery. Small, wooden carts pulled by white donkeys along unpaved roads. Wherever you look, relics of the past stand in full view, giving you a visual sweep of Siwa’s long history.