040

Ancient texts are different from modern books. Today copyright laws not only assure the author his or her fair share of royalties, but also that the text printed is the text the author wanted to print. Before the introduction of copyright laws, many diverse texts for a single work circulated. Some publishers copied their base text exactly, others shortened it, while others expanded upon it. In addition, different copyists used different manuscripts as the basis for their editions. All of these things happened to the text of the Bible. Since the most important manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible are hundreds of years old, it is not surprising that they do not all agree. Studying the different manuscripts is important, both to understand how one text relates to another and to decide which version or text is closest to the original.

The texts of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament have very different histories. The Hebrew Bible reflects material written in the course of a millennium, while the entire New Testament was composed within a century. The transmission of the Hebrew Bible began long before the New Testament was written. It is therefore not surprising that the history of manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible is not parallel to those of the New Testament, which was described in a recent Glossary.a

The major distinction among texts of the Hebrew Bible is whether they are vocalized or unvocalized. This distinction is based on certain peculiarities of the Hebrew writing system. In its earliest written stage only the consonants of any Hebrew word were written down; there were no signs for the vowels. For example, the word for “word” would be written

Starting probably in the eighth century happened B.C.E.b, certain consonants (

In the second half of the first millennium C.E., a tradition developed of adding separate vowel signs to biblical texts. For example, the ambiguity of the written word

These vocalized texts are typically called Masoretic texts, after the Masoretes, a group of scholars who introduced the vowel system and other innovations in order to safeguard the traditional reading of the text. The term derives from the Hebrew root MSR (to hand over or transmit, or to count); the Masoretes tried to ensure proper transmission of the Hebrew text through the precise counting of its letters. When a manuscript was copied, the number of letters in it was compared to the original; if the numbers did not match, an error in copying must have crept in. Unvocalized manuscripts preceding the rise of the Masoretic schools are called pre-Masoretic texts. Most pre-Masoretic texts have been found within the last half-century in the caves at Khirbet Qumran, near the Dead Sea. Some of the Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran and elsewhere rather closely resemble the consonantal skeleton of the later Masoretic versions. These are called Masoretic-type texts or proto-Masoretic texts.

The Qumran manuscripts are the oldest substantial biblical texts. They include at least portions of every book in the Hebrew Bible except the Book of Esther. Most of the scrolls, however, are either very fragmentary or contain only a few sections of a few chapters. One exception is the manuscript called 1QIsaa,1 which is 54 columns long, an almost completely preserved manuscript of the entire Book of Isaiah. Even though some scrolls from Qumran are a full millennium older than the oldest fully vocalized Masoretic texts, printed texts of the Bible are still based on the later Masoretic text because the manuscripts from Qumran are so fragmentary.

Because the pre-Masoretic manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible are for the most fragmentary and the Masoretic manuscripts are comparatively recent, ancient translations of the Hebrew Bible play a major role in reconstructing the biblical text. These translations, collectively called “the (ancient) versions,” are translations of the text of the Hebrew Bible into Greek (the Septuagint and others), Latin (the Vulgate and others), Aramaic (the Targumim), Syriac (the Peshitta) and other languages. Translation began in the latter portion of the first millennium B.C.E., as Jews in certain communities began to become more familiar with Greek and Aramaic than with Hebrew.

041

The earliest written translation that we know of was into Greek, for the sake of the Jewish Hellenistic community living in Alexandria, Egypt.c This translation, the Septuagint, was probably begun in the third or second century B.C.E. Relatively complete manuscripts of the Septuagint written in the fourth and fifth centuries C.E. still exist. To the extent that these are accurate, literal translations, these Septuagint manuscripts are extremely important, because they may be our earliest evidence for the continuous text of the Hebrew Bible. The Torah text of the Samaritan community, called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is also an important tool for reconstructing an early biblical text. It differs in many places from the Masoretic text; these differences often reflect sectarian bias, but sometimes accurately preserve ancient non-Masoretic readings.

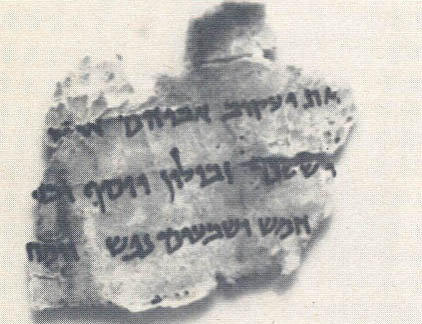

The Dead Sea Scrolls are not only important for the variant readings they preserve, but they have also played an important role in evaluating the ancient translations. Before the scrolls were discovered, people could claim that the Hebrew Masoretic text known from the end of the first millennium C.E. and later was the only text worth interpreting. Some scholars claimed that the places where the ancient translations differ from the Masoretic Hebrew text reflect mistranslations. They denied the possibility that these ancient translations were working from a non-Masoretic text. However, certain Dead Sea Scrolls have been discovered that have a Hebrew text that is very close to the one the Septuagint must have been translated from. One such text is reproduced below, left. It is a copy of Exodus found in Qumran Cave 4 called 4QExb.d This fragment contains a short section of Exodus 1:1–5. In its three fragmentary lines it twice diverges from the Masoretic text in agreement with the Septuagint: In verse 1 it adds the word for “their father,” found in the Septuagint but lacking in the Masoretic text, and in verse 5 it gives the number of Jacob’s descendants as 75, in agreement with the Greek translation but in contrast to the Masoretic text’s 70. The existence of such manuscripts indicates that disagreements between the Septuagint and the Masoretic text are not always the product of errors by the Greek translator. In fact, as 4QExb and other manuscripts make clear, the translators were sometimes working from a Hebrew text which in places differed from what we now call the Masoretic text.

Ancient manuscripts are not always superior to more recent ones. The quality of a manuscript depends on its scribes, especially on how precisely they copy the manuscript before them, preserving its outdated features rather than updating them. At Qumran we see a variety of text types—some of which are nearly identical to the consonantal text that appears later as the Masoretic text, while others are quite divergent from it. For instance, the Great Isaiah Scroll is a text that was modernized by a scribe to conform to contemporaneous grammatical norms.

The evidence from Qumran suggests that up to 68 C.E., the year in which Khirbet Qumran was destroyed, there was no single, unified biblical text. We find diverse readings in equivalent biblical texts at Qumran, as well as in sectarian commentaries, called Pesher texts,2 which sometimes offer comments on two different forms of the same biblical text. This suggests that in this period a text could be considered holy and authoritative even though a definitive version of it did not yet exist.

Exactly when and how the text stabilized is not known. By the second century C.E., a method of close reading of the biblical text which expounded forms of words that were spelled in an unusual way had developed. This method of interpretation, which is one of the characteristics of the rabbinic midrash, seems to presuppose a fixed form for the biblical text. Second-century C.E. biblical manuscripts discovered in Wadi Murabba’at (a site between Jericho and Ein Gedi) and elsewhere also provide evidence of texts that are very close to what we know later as the Masoretic text. Thus, the biblical text had probably stabilized in a form very closely resembling the Masoretic text by the second century C.E.

Some scholars claim that a silver amulet found in Jerusalem, dating from about the seventh century B.C.E., gives an important piece of evidence for the early stages of the biblical text. The tiny, delicate rolled scroll contains a text very similar to the priestly blessing in Numbers 6:24–26: “May the Lord bless you and keep you; may the Lord cause his countenance to shine upon you, and be gracious to you; may the Lord favor you, and grant you peace.” The amulet preserves a text that is somewhat shorter than the Masoretic version. However, the amulet’ text should not be considered a quotation form the Bible; rather it probably quotes a precursor to the priestly blessing that was later preserved in Numbers 6:24–26.

Another source for an early biblical text is the Nash Papyrus, probably a liturgical fragment dating from the second century B.C.E. It contains a version of the Decalogue—the Ten Commandments—and part of the Sh’ma prayer (Deuteronomy 6:4–5). In several places, for example in the ordering of the “Thou shalt not” commandments in the Decalogue, the 042Nash Papyrus differs from the Masoretic text; in some of these, it resembles the Septuagint. Before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, this papyrus was the oldest biblical fragment known.

Many tefillin (phylacteries) and mezuzot (doorpost inscriptions) excavated at Qumran and elsewhere in the Dead Sea area, including Masada, also contain deviations from the biblical text. However, these are not carefully written biblical manuscripts but carelessly written liturgical texts, so they have little value for reconstructing biblical texts.

In the second half of the first millennium C.E. the codex—or book form—was introduced for nonliturgical use. Even more significant than the change from scroll to codex was the development of Masoretic Bibles in this period, that is Bibles with vowels, accents and cantillation marks, namely notes reflecting the chanting of the text in liturgical and academic contexts. Some also had marginal (Masoretic) notes which helped preserve the integrity of the text. Evidence preserved in texts from the Cairo Genizah3 shows that these developments were part of a gradual process, and that different types of notations were developed in different centers of Jewish activity. The main systems of vowel notation are called Babylonian, Palestinian and Tiberian. The system that ultimately prevailed was the Tiberian system, developed in the city of Tiberias in Israel and closely associated with the famous family of scribes, the Ben Ashers. Today, all printed editions of the Bible use the Tiberian system of vocalization, which places most vowel points, or markings, below the consonants and typically places the cantillation marks on the accented syllable.

The finest of all the extant Masoretic Bible manuscripts is the Aleppo Codex, named after the city in Syria where it was housed before it was brought to Jerusalem. It is a beautifully written codex (see below), completed in the late tenth century C.E. in Israel. It was the oldest known manuscript of the entire Hebrew Bible, and it is quite possibly the first vocalized Hebrew manuscript of the complete Hebrew Bible ever written. Unfortunately, it is no longer complete, since much of the Torah (Pentateuch) and some other sections were destroyed during an Arab pogrom against the Jewish community of Aleppo in 1947. The Aleppo Codex had great authority in the medieval period. It was often consulted by scribes to correct other manuscripts. Maimonides, the important medieval Jewish philosopher and jurist (1135–1204), used its paragraph markings as the standard that Torah scrolls must follow. However, since the Aleppo Codex has only recently become available in facsimile edition and because it is now incomplete, the Masoretic manuscript used for most scholarly work is the one in the collection of the Leningrad Public Library, called Leningrad B19A, probably dating from 1008. This manuscript is full of erasures and corrections that indicate that it has been revised in accordance with the Aleppo Codex or some very similar manuscript.

There are a few other extant Masoretic manuscripts of sections of the Bible that antedate Aleppo. The Cairo manuscript of the Prophets written in 896 by Moses ben Asher, housed in the Karaite Synagogue in Cairo, has a slightly different vocalization system than Aleppo. However, compared to the differences among the Dead Sea Scrolls of a millennium earlier, the variances among Masoretic manuscripts are minuscule. Although many other medieval manuscripts contain readings that diverge from Aleppo or Leningrad, in almost all cases these variant readings are the product of errors by medieval scribes rather than accurately preserved, ancient traditions. Thus, for reconstructing the standard Masoretic text, it is sufficient to use the Aleppo Codex and its closely allied manuscripts, such as Leningrad B19A.

The histories of Hebrew Bible and New Testament manuscripts are distinct in several respects. Although the Hebrew Bible was composed before the New Testament, the earliest complete manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible—the Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad B19A—are half a millennium later than those of the New Testament. Since complete manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible are relatively late, the ancient translations of the Bible, which reflect earlier Hebrew texts that are no longer extant, play a much larger role in textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible than of the New Testament. Finally, the early manuscripts of the New Testament give a complete picture of the pronunciation of the Greek text because Greek writing, like English, specifies both vowels and consonants. In contrast, the manuscripts from Qumran only represent the consonantal shell of the Hebrew Bible, with all of its ambiguities, so that the biblical text’s pronunciation and meaning must sometimes depend upon vocalized texts from the end of the first millennium. For these reasons, textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible and of the New Testament have developed, and will continue to develop, as two separate disciplines.

I would like to thank Michael Carasik of Brandeis University for assisting me in writing this article.

Ancient texts are different from modern books. Today copyright laws not only assure the author his or her fair share of royalties, but also that the text printed is the text the author wanted to print. Before the introduction of copyright laws, many diverse texts for a single work circulated. Some publishers copied their base text exactly, others shortened it, while others expanded upon it. In addition, different copyists used different manuscripts as the basis for their editions. All of these things happened to the text of the Bible. Since the most important manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible are […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Footnotes

B.C.E. and C.E. are the scholarly, religiously neutral designations corresponding to B.C. and A.D. They stand for “Before the common Era” and “Common Era.”

If this prophecy could be reinterpreted in this way to refer to later events, phrases like “in the latter days” would be reinterpreted to refer to the “end of days.”

See Mathew Black, “The Strange Visions of Enoch,” BR 03:02.

Endnotes

Y. K. Kim. “Palaeographical Daring of

Bruce Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1968), pp. 40–41.