Past Perfect: Finding Akhenaten’s Daughter

The British author Mary Chubb uncovers an ancient Egyptian statue

Mary Chubb (1903–2003) attended art school and taught Latin before joining London’s Egypt Exploration Society as a secretary. In the 1930s she participated in the society’s dig at Tell el-Amarna, Egypt, where the “heretic” pharaoh Akhenaten (1353–1336 B.C.) established a short-lived capital called Akhetaten. Chubb had the good fortune to unearth an exquisite 2-inch-high head, which dig director John Pendlebury identified as a likeness of Ankhesenpaaten, one of Akhenaten’s daughters and the wife of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1332–1322 B.C.). Chubb’s 1954 book Nefertiti Lived Here recounts her experiences on the Amarna dig; the excerpt on the following pages tells of her thrill in discovering Ankhesenpaaten’s face amid “the yielding rubble.” In later years, Chubb described her experiences excavating the Mesopotamian city of Eshnunna, and she wrote a series of children’s books about ancient Rome, Greece, Egypt and the Holy Land. In her obituary, the Times of London praised Chubb’s gift for combining “scholarship and fun, the personal and the intelligently treated distance.”

The afternoon wore on and the heap had been reduced to a foot or so above ground level, when my brush moved over something curved and hardy, perhaps a big stone. I blew away the sand, and saw a grey-white ridged surface, with flecks of black paint; certainly not a stone. Hilda [dig director John Pendlebury’s wife, and a trained archaeologist in her own right] and an excavator leaned over and looked. “Try getting the stuff away from the front,” she said. “We ought to get a look at it from another angle, before it’s moved.” I came round and began brushing and blowing at the vertical side of the heap. Down trickled the sand between the harder bits of mud brick, like tiny yellow waterfalls, and nearer and nearer I came to the side of the buried object. A final gentle stroke with a brush tip, and the whispering sand slid away from the surface—and we could see more of the grey and white ridges, and beneath it a smooth curve of reddish-brown paint. The sand had poured away below it and left a cavity. “Can you see inside the hollow?” Hilda asked. I lay down flat and got one eye as close as I could to the rubble.

And then I suddenly saw what the brownish paint was—part of a small face. I could just see the curved chin and the corner of a darker painted mouth. Hilda knelt up and beckoned to John [Pendlebury], who was not far away.

“It’s the head of a statue, I think,” she said quietly as he joined us. He took a long look, and then sat back on his heels. His face was very compressed and tense.

“I’ll wait while you get it out,” was all he said.

Infinitely slowly we cut back the caked rubble in which it was embedded. The hardest thing on earth is to go slow when you are excited. But we had to—we could never tell how strong or how fragile a find was until it was finally detached from its hiding-place. For all we knew there might be a crack right across the unseen face, so that the whole thing might crumble into powder at a clumsy movement.

We widened the cavity just beneath it, so that John could get his fingers into it in case the head dropped suddenly. He held them there unmoving for at least five minutes, while we worked round the top. “It’s coming,” he said suddenly.

Hilda blew once more at the surface, and the head sank onto John’s hand. He drew it slowly away from the debris. Then very gently he turned the head over on his palm.

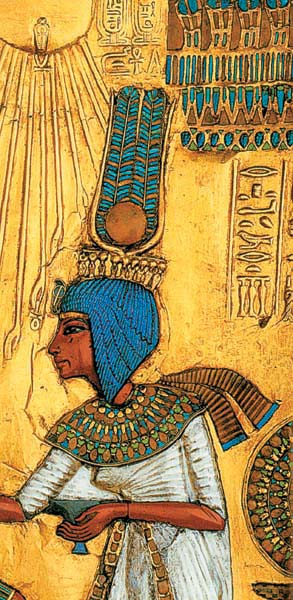

Framed by a dark ceremonial wig, the face of a young girl gazed up at us with long, beautifully modeled eyes beneath winging dark eyebrows. The corners of the sweet, full mouth drooped a little. The childish fullness of the brown cheeks contrasted oddly with the tiny determined pointed chin. Somehow the sculptor had caught the pathetic dignity of youth burdened with royalty. The little head was another exquisite example of the genius of the sculptors of Akhenaten’s day for perceiving more than the surface truth, and expressing to perfection what they had seen.

I looked up from the head to John’s face. In those few moments it had completely lost its gaunt grey look of the past few weeks. He knelt there in the dust, brown and radiant, looking down at the beautiful thing on his hand.

“Now,” he said slowly, “our season has been crowned.”

That evening the sky beyond the motionless trees flamed rose and gold with the promise of more calm days to come; and the Nile was marvelously quiet again.

The lamp was already lit when Hilda and I came into the living-room after locking up the medicine cupboard. John had the little head on the table alongside a book open at a photograph of one of the chairs found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The others were round him, and we joined them. On the leather back of the chair there is a very beautiful scene wrought in sheet gold and silver and costly stones and coloured glass, showing the young Pharaoh seated, leaning casually back, one bent arm hitched over the back of his chair. He is looking gently at his little Royal wife, Ankhensenpaaten, third daughter of Akhenaten. She stands before him, leaning a little forward, rather confidingly, with her right hand gently touching, perhaps patting, his shoulder. John turned the limestone head so that it showed exactly the same view as that in the picture—the left profile.

The likeness was astonishing: the same long eye and dark eyebrow; the same delicate nose; the full mouth, with the little droop where the young cheek curved over towards the small pointed chin. The wigs too were identical in shape.

“I think she must be Ankhesenpaaten,” John said finally …

It was only now that I knew the true exhilaration that comes from literally unearthing a treasure which in one flash eliminates time; when the ancient artist speaks direct through his creation to all those coming after, who understand his language …

The wonder of touching something that had lain buried and unmoving for so long came over me again, just as I’d felt when I was new to all this, four months ago. But I’d found that to say: “This was made three thousand years ago” now hardly stirred my sense of time at all. But I thought of it this way: The little head, wedged in that rubble, up against a ruined wall in this silent, sunny place in Egypt, had been lying there, face downwards, while Troy was burning; while Sennacherib was ransacking the cities beyond his borders, on through the slow centuries, while the greatness of Athens came and went, and while Christ lived out his days on earth. It was still lying there when the Romans first marched on London, when Harold fell at Hastings, and the last Plantagenet at Bosworth Field. On and on through the years, until this hot afternoon when the brush and knife came nearer and nearer to it through the yielding rubble, until it stirred, dropped, and lay once again in a warm human hand. From Mary Chubb’s Nefertiti Lived Here (London: Geoffrey Bles Ltd, 1954).

Mary Chubb (1903–2003) attended art school and taught Latin before joining London’s Egypt Exploration Society as a secretary. In the 1930s she participated in the society’s dig at Tell el-Amarna, Egypt, where the “heretic” pharaoh Akhenaten (1353–1336 B.C.) established a short-lived capital called Akhetaten. Chubb had the good fortune to unearth an exquisite 2-inch-high head, which dig director John Pendlebury identified as a likeness of Ankhesenpaaten, one of Akhenaten’s daughters and the wife of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1332–1322 B.C.). Chubb’s 1954 book Nefertiti Lived Here recounts her experiences on the Amarna dig; the excerpt on the following pages tells of her […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.