Canceled!

A new traveling exhibition of 5,000 years of Georgian art is already ancient history

042

043

Look at this crucifix,” said Gary Vikan, the director of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore. He pushed a book across the table and pointed to a photograph of a silver sculpture of Jesus nailed to the cross. The statuette was made in tenth-century A.D. Georgia, on the east coast of the Black Sea. Jesus’ face, hair and waistcloth, as well as the cross itself, are covered with gold; Jesus’ head tilts softly to his right, while his body is taut and angular, as if stretched on a rack.

“There’s no Byzantine equivalent for that,” Vikan continued. “No Greek or Russian would have made an icon in relief. The theology of the sacred image put a premium on transparency, a layer of paint on a piece of wood, for example. The Georgians acknowledged the weight of the body; they wanted it to come out from the surface—the comfort of a three-dimensional image sculpted in precious metal. It’s absolutely astounding.”

The silver crucifix, one of 150 objects in an exhibition of Georgian art, called Land of Myth and Fire: Art of Ancient and Medieval Georgia, was scheduled to travel from Georgia to the Walters last October, and to San Diego and Houston next year. But today the crucifix remains in an art museum in the Georgian capital, Tbilisi. Nearby lie packing crates, still empty, specially designed to transport fragile works of ancient art.

On August 4, 1999, after two years of preparations and outlays of about a million dollars, the Walters issued an official statement calling off the show. Georgian president Eduard A. Shevardnadze, facing protests from opposition members, the Georgian Orthodox Church, university students and some scholars, was unwilling to let the ancient silver and gold sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, textiles and religious icons out of the country.

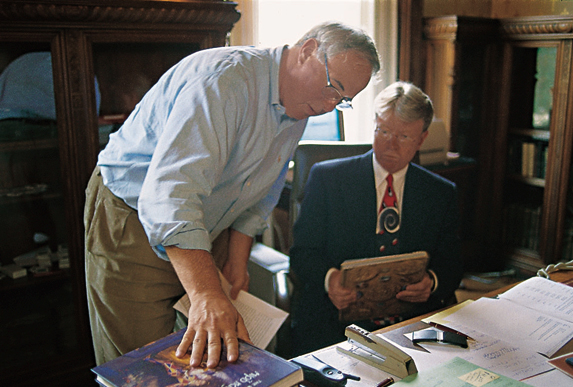

A week later, Vikan was anxious to discuss the exhibition that wasn’t to be. An expert in Byzantine art, the director of the Walters is a dapper, nervous 044man with a shock of silvering blond hair. He darts about his high-ceilinged office—dominated by a large, stern portrait of gallery founder Henry Walters—checking his e-mail, rustling through papers, conferring with staff members. Then, in a flash, he is back on subject, talking animatedly about his “almost mythical sense of the significance of medieval art,” his blue eyes intensely focused behind steel-rimmed glasses.

“I’ve never seen anything like this before,” Vikan said, staring at the crucifix. “Around 1200, Georgia was the preeminent creative force in [Christian] Orthodoxy.”

The Georgian national exhibition, as it is called, was the brainchild of Gregory Guroff, president of the Foundation for International Arts and Education in Bethesda, Maryland. Guroff, a fluent Russian-speaker, has worked at the U.S. embassy in Moscow and made, since the 1960s, numerous trips to Soviet Georgia and the Republic of Georgia. In late 1997 he was approached by the Georgian ambassador in Washington, Tedo Japaridze, who suggested that the foundation arrange a traveling exhibition of Georgian art. Japaridze indicated that such an exhibit would have the backing of President Shevardnadze.

Intrigued, Guroff went to Helen C. Evans, curator of the 1997 exhibition Glory of Byzantium at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Guroff explained that he wanted to organize a show on Georgian Byzantine art to tour the United States. 045Evans knew that there might be difficulties: The Met had originally intended to include about a dozen Georgian objects in Glory of Byzantium, but after much haggling, it had to settle for just five pieces. Evans sent Guroff to the obvious candidate, her close friend Gary Vikan, a prominent Byzantine scholar who also headed a major museum.

Vikan didn’t need much convincing. In 1981, while attending the International Byzantine Congress in Vienna, he had seen an exhibition of Byzantine art that included the lovely gilded silver crucifix and other objects on loan from Georgia. He told Guroff: “Let’s do this exhibition.”

The following spring, in May 1998, Vikan and Guroff flew to Tbilisi. The next morning, Vikan entered the archaeology museum—one of three museums, along with the state art museum and a manuscript institute, that were to furnish the objects in Land of Myth and Fire. The first thing he saw, in an illuminated vitrine near the museum’s entrance, was a tiny golden lion, dating to the late third millennium B.C.; near the lion was a delicate, 18th-century B.C. gold cup, studded with semi-precious stones. “The vice-director of the museum was with us,” Vikan said. “He was very gleeful and kept saying, ‘Why don’t you take this and this and this?’ The exhibition, I realized, would not only be exciting; it would go far beyond the Middle Ages.” The show had suddenly expanded: It would cover 5,000 years of Georgian art.

Even at this early stage, however, there were signs of trouble to come. The curator of the state art museum, which houses all of the religious objects, was willing to part with textiles such as Eucharist cloths and shrouds, many decorated with gold and silver thread and encrusted with pearls. But he drew the line at metal objects—the gilded silver cross, embossed gold and silver relief scenes of gospel stories and the saints, cloisonné enamels and golden Eucharist cups. He was worried that these pieces were too fragile. In the past, he said, objects had been sent to France and come back badly damaged.

A similar sentiment was expressed by a Georgian Byzantine scholar with whom Vikan had maintained a correspondence for 15 years. During the May 1998 visit, Vikan asked her what she thought about the possibility of sending Georgian treasures to be displayed in the West. She answered metaphorically, according to Vikan, “I’d rather have my child die of starvation at my side than send the child away with the prospect of our never meeting again.”

Vikan summarized these fears as “the endgame of a bad dream,” that is, the fatalism of a people who for centuries have not controlled their destiny. Georgia’s proud ancient traditions—particularly her famed metalsmiths, who forged delicate gold goblets and inlaid them with glowing turquoise or flashing garnet—may have inspired two legends known throughout the Western world. In Greek myth, Zeus chained Prometheus to a rocky promontory in the Caucasus Mountains, which form Georgia’s northern border, as punishment for giving man fire. Another Greek myth has Jason and the Argonauts visiting western Georgia, called Colchis by the Greeks, in search of the Golden Fleece; it is said that the rivers of Colchis flowed so profusely with gold that the natives simply strained it out with sheep’s wool. (The title of the national exhibition, Land of Myth and Fire, is a direct reference to these stories and the penchant of ancient Georgian goldsmiths to inlay their creations with brilliant gemstones.)

For much of the last 2,000 years, however, the Georgians have been ruled by Persians, Byzantine Greeks, Arab caliphates, Turks and the Soviet Union. During a brief period from the early 11th century to the late 12th century, Georgia was united under a 046series of kings, the most famous being David the Builder (1089–1125). This was the period in which Georgia, in Vikan’s words, became the principal creative force in Christian Orthodoxy—producing its most magnificent icons, its illuminated manuscripts, and its national epic, The Knight in the Panther’s Skin by the 12th-century poet Shota Rustaveli.

“They were telling me something simply but eloquently,” Vikan said of those who expressed doubts about allowing Georgia’s ancient artwork to leave the country. “These people understand who they are by virtue of two things: shared language and shared religion. The physical manifestation of the two is the stuff in those vaults. It is for them the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Magna Carta and the Mona Lisa.”

During that visit of May 1998, Vikan and Guroff were summoned to what they thought was a meeting with President Shevardnadze. Instead, they were met by Georgia’s vice president, who presented them with a protocol signed by Shevardnadze. It contained five or six bullet points enumerating the steps the Americans would have to take as their part of the bargain. Among the steps, the Americans were to train Georgian conservators, perform conservation work on deteriorating objects and help arrange an exhibit on 2,600 years of Georgian Jewish history. The Americans agreed. (The Jewish exhibit, it was later determined, would accompany the national exhibit on its tour—to be displayed at the Meridian International Center in Washington, D.C., in October 1999 and then traveling to San Diego and Houston in 2000. It, too, has been canceled. See the second sidebar to this article.) In an interview in Vikan’s office last August, Guroff said that the protocol’s unstated, though fundamental, message was, “If the president chooses to do something, it will be done.”

With the national exhibition underway, the Walters seemed the perfect venue. The main appeal of the show would lie in the Byzantine works crafted during the floruit of Georgian culture in the 11th and 12th centuries—Vikan’s area of expertise. The marriage was also a happy one for another reason: The specialties of two of the Walters conservators, Terry Drayman-Weisser, an authority on metals, and Abigail Quandt, who works on manuscripts (such as the recently discovered tenth-century A.D. palimpsest with works by Archimedes),a exactly matched the needs of the Georgians.

Many of the Georgian works, including the silver crucifix, had corroded badly since Vikan’s 1981 visit to Vienna. Walking through the state art museum, he noticed that the display cases were unsealed, allowing dust to settle on the objects. In the manuscript institute, a smell of turpentine lingered in the air, the electricity didn’t work and damp drafts could be felt flowing through the air-conditioning ducts. A number 047of manuscripts—Psalters, illuminated gospels, astronomical treatises, illustrated editions of Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin—could not be opened for fear that the pages would crumble and the gold paint from the illuminations would flake off. Another text, the Lailashi Pentateuch, an 11th-century Hebrew Torah probably copied in Greece, is also desperately in need of repair.

Conservators Weisser and Quandt made a preliminary trip in June 1998 to determine whether the materials chosen for the exhibition were fit to travel. Their answer was yes, with a caveat: Without significant restoration, many objects risked severe, permanent damage—whether they traveled or not. As Georgia’s museum personnel lacked the technical expertise to repair the items, Guroff’s foundation arranged for Georgian conservators to visit Baltimore, to see what could be done and receive training.

The Georgians were dazzled by what they saw in one of the Walters’ conservation labs. “They were watching Abigail [Quandt],” Guroff recalled, “who happened to be working on a manuscript. She was restoring the ink and gold and securing the manuscript by using staples. Their eyes nearly popped out of their sockets; they were even dancing. This didn’t involve high-powered equipment, only simple techniques and the correct materials. So they became very excited.”

The Walters conservators made two other trips to Tbilisi, where they met with curators and scientists and advised museum officials on how to store, preserve and display fragile works of ancient art. But wherever they turned, it seemed, someone was expressing the painful fear that Georgia’s cultural heritage would be lost forever. On her last visit, in early July 1999, Weisser met with an expert in metals from Georgia’s metallurgical institute in Tbilisi:

“We went to the art museum and stood in front of the objects. We were having this fairly scientific conversation about ions and atoms and corrosion products and gasses, using formulas and all that. The art museum treasury is built right over a sulfur spring. It’s a closed-in room with no ventilation, and the walls and display cases are lined with a dark blue wool felt, which gives off corrosive, sulfurous gasses. That’s why the objects are so black; they are black as shoe polish. And he [the Georgian metallurgist] understood the science. ‘Why leave them here,’ I asked him, ‘where they’ll get worse?’ He said: ‘It’s God’s plan that these objects stay here and die here’.”

For Weisser, in retrospect, the conversation with the Georgian scientist presaged the end of the exhibition.

Shevardnadze officially announced the exhibition during his visit to Washington for the NATO conference in late April 1999. Then he and ambassador Tedo Japaridze visited the White House and invited President Clinton to the opening.

By this time, Guroff had gone to major corporations to fund the show: Chevron, Metro Media, the Rockefeller Foundation. Arrangements had been made for the Georgian national exhibition, after leaving the Walters, to travel (with the accompanying Jewish exhibition) to San Diego and Houston. A catalogue, written by a group of scholars and full of color pictures of the 048objects, was to be printed in London. Scholarly conferences on Georgian art, training sessions for conservators, a film on life in Georgia had been organized.

The day after Shevardnadze’s announcement, he was denounced in the Georgian parliament. Rumors floated in the Georgian media that the Americans were planning to copy the originals and send back duplicates. A number of museum officials and scientists expressed the opinion that the objects were too fragile to travel. In front of one of the museums, university students organized hunger strikes, which were forcefully disbanded by the police. The police action against the students was witnessed by Dodona Kiziria, a native Georgian who is a professor of Slavic literature at the University of Indiana. “It was brutal, cynical and humiliating—the beating of those young people,” Kiziria, who publicly opposed the Georgian national exhibition, said in a telephone interview. “And they [the students] were accused of being Zviadists [followers of the first president of the Republic of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, who was deposed in January 1992 in an armed coup and who died two years later under mysterious circumstances]. But they were only eight or nine during Zviad’s presidency; they’re anything but Zviadists.” In Kiziria’s view, the behavior of the police brought deep-seated resentments to the surface; the Shevardnadze government, many people believed, was as haughty and autocratic as its Russian predecessors.

The patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox Church, an independent church that traces its roots back to the fourth century A.D., was traveling in the Netherlands. Patriarch Ilia II issued a statement that holy objects should not leave Georgia. If they did, they would lose their holiness. Soon afterwards, the patriarch “restated”—Guroff prefers to use the word “changed”—his position: No sacred objects should leave Georgia in the millennial year 2000, because many Christians would be making pilgrimages to Georgia to see its ancient icons.

In early May, about a week after Shevardnadze publicly announced the Georgian national exhibition, Guroff and Vikan dove into the hornet’s nest. “We arrived in Tbilisi and were treated to incredible media attention,” Guroff said. “Gary [Vikan] and I became television stars.” The American embassy in Tbilisi arranged a press conference the first night, and over the next few days the director of the Walters and the head of the American foundation appeared frequently on television and radio, trying to squelch rapidly growing fears that the objects in the exhibition would be damaged in transit or sold off—either by the Americans or by the Shevardnadze government to finance the national debt.

“It was not a rational debate,” Guroff lamented, a week after the exhibit was canceled. “So it didn’t matter what we said.”

The coup de grace, for Vikan, came during a visit to the patriarch. The meeting started about 8:15 p.m. and was attended by Patriarch Ilia II, various church 049officials, a representative from the American embassy and some members of the Georgian Academy of Sciences.

The guests were assembled in a large room in the patriarch’s residence. A row of high-backed medieval chairs fanned out, in a V-pattern, from a large gold box with a glass panel containing a sacred shroud with an image of Jesus Christ. A full-bearded, smiling Patriarch Ilia II entered the room, wearing flowing black robes and a burgundy hat with a diamond cross. He took a seat near the shroud, and the guests were seated, more or less in order of rank, outwards along the prongs of the V. Then everyone gave speeches.

“Maybe an hour and 45 minutes have gone by,” Vikan recalled. “I was looking at the patriarch, who has a very kind, full face. He is robust, and when he smiles, his teeth glisten. Then people come in and put little tables in front of us: one table for two, one table for two. I knew we were in for the long haul. There was magnificent espresso, a shot of cognac, white raisins, walnuts and a plate with cinnamon cake.”

Then the patriarch began to speak, Vikan related: “The Christian art belongs to the church, he said; it shouldn’t go anywhere. It shouldn’t leave because of the millennium. And he said there’s a lot of Georgian art out there in the world, why don’t you get that? He’s wrong. There’s not a lot of Georgian stuff. We have one little piece. The Met has a few enamels.”

When the patriarch finished, he summoned two men into the room. “They were wearing typical East European gray suits, the ones that stand up by themselves,” said Guroff. Out of a briefcase the men pulled a plastic hologram of Jesus and held it out under the room’s enormous chandelier, so that the image danced and sparkled. The patriarch was offering the Americans a compromise; they could have the hologram and Georgian art from foreign museums, which, according to Vikan, doesn’t exist.

“I’d dragged three of the staff over there,” said Vikan, “and I’m thinking, Jesus, we’re going home tomorrow. It’s time to quit.”

What kept them from quitting were repeated assurances, during that May 1999 visit, and then in June and July, that the government backed the exhibition. The president wanted the show to go on, and go on it would.

The national exhibition was to open at the Walters on October 26. Several of the badly damaged items were to arrive in August, allowing the conservators time to prepare them for the show. Prior to shipping, each 051item was to be placed in a custom-made box, which was to be placed in a larger crate. On July 1, the special shipping crates were flown to Tbilisi, but Georgian customs delayed and delayed, unwilling to let them out of the airport. Then the Georgian courier who had been selected to accompany the objects was denied permission by the government to apply for a U.S. visa. “What was becoming clear,” said Guroff, “was that the government was petrified of the opposition and was trying to get out of the deal.”

By late July, the empty crates had cleared customs and were in place in the museums, waiting to be packed. But then Shevardnadze pulled the plug. Facing stiff resistance from his political opposition, the church, the media and the general public, Shevardnadze joined Patriarch Ilia II in a statement that, as leaders of Georgia, they did not wish to divide the nation. The traveling exhibition of 5,000 years of Georgian art was canceled.

Everyone agrees, those who support the show and those who are against it, that Shevardnadze withdrew his support for political reasons. National elections were to be held in November 1999, and Shevardnadze calculated that the growing contention was a political liability. So he cut his losses.

Guroff goes further: Westward-looking Georgians, who welcome the influx of ideas, hoped that the show would bring Georgia into the community of nations; they were opposed by the insular Old Guard, which is mired in the past and fearful of change. On one side stood Shevardnadze; on the other, Patriarch Ilia II. The opposition to the show, says Guroff, had nothing to do with whether the objects were too fragile or too holy to travel. It was simply disguised opposition to Shevardnadze himself.

So who loses?

Clearly, the objects that would have been restored by American conservators will suffer. As it is, no one in Georgia dares even to open many medieval manuscripts, for fear that they will fall apart. The Walters conservator for objects, Terry Weisser, cites an early iron sculpture of a male figure; some years ago, the Georgians had tried to restore the piece by using a solution that ate away at the metal. They then immersed it in shellac, creating an ugly, plastic-looking object. Weisser could have fixed the statuette. Now the damage to the appliqué medallions, silver and gold chalices, cloisonné enamels, wooden icons and colorful woven tapestries illustrating acts of the saints will only accumulate.

And the world suffers for being denied access to Georgian art—a synthesis of Persian, Byzantine and Arabic styles disciplined and inspired by something uniquely Georgian.

“The secret to Georgian art lies there,” said Vikan, pointing across the table to two photographs. One shows a 16th-century A.D. icon of Jesus painted on wood; the image is framed with gold leaf inlaid with turquoise, rubies, lapis lazuli and garnets. The other photograph shows a beautifully crafted golden bowl, from the early second millennium B.C., also inlaid with gemstones. “They are separated by 3,500 years, but they are united by a common thread: the affinity of precious metals and semi-precious stones,” Vikan said. “It’s not the image of Jesus at the center that characterizes Georgian art, but rather how the gems are laid on top of the gold, as if dripped across the surface.” Whether Bronze Age or Byzantine, Vikan said, “it’s Georgian from beginning to end.”

Look at this crucifix,” said Gary Vikan, the director of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore. He pushed a book across the table and pointed to a photograph of a silver sculpture of Jesus nailed to the cross. The statuette was made in tenth-century A.D. Georgia, on the east coast of the Black Sea. Jesus’ face, hair and waistcloth, as well as the cross itself, are covered with gold; Jesus’ head tilts softly to his right, while his body is taut and angular, as if stretched on a rack. “There’s no Byzantine equivalent for that,” Vikan continued. “No […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “Archimedes Takes Center Stage,” Field Notes, AO 02:04.