Parallel Histories of Early Christianity and Judaism

How contemporaneous religions influenced one another

042

Everyone knows that Judaism gave birth to Christianity. But the formative centuries of Christianity also tell us much about the development of Judaism. As formative Christianity demands to be studied in the setting of formative Judaism, so formative Judaism must be studied in the context of formative Christianity.

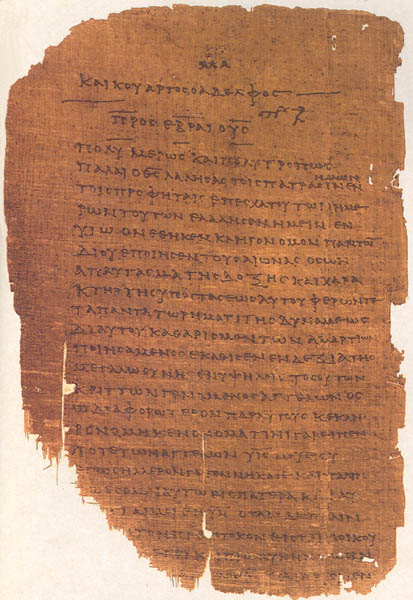

Both Judaism and Christianity rightly claim to be the heirs and products of the Hebrew Scriptures—Tanakha to the Jews, Old Testament to the Christians. Yet both great religious tradition derive not solely or directly from the authority and teachings of those Scriptures. They reach us, rather, from the ways in which that scriptural authority has been mediated, and those biblical teachings interpreted, through other holy books. The New Testament is the prism through which the light of the Old comes to Christianity. For Judaism, the rabbinic corpus serves the same function. The corpus of the New Testament is well known.

The distinctive corpus of rabbinical Judaism, the so-called oral Torah, is less well known, but it is the star that guides Jews to the revelation of Sinai, the Torah.

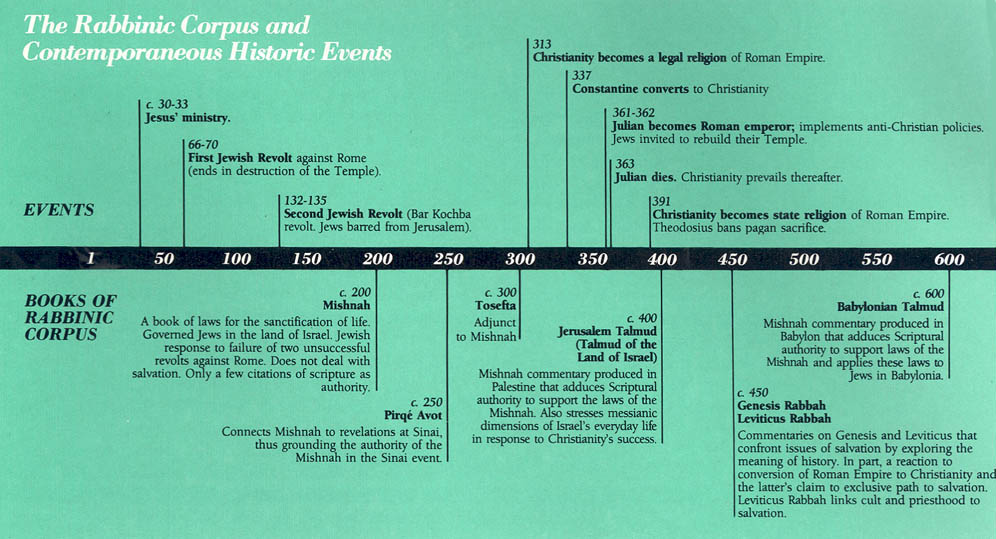

The rabbinic corpus—what we might think of as the historical parallel to the New Testament— consists of the Mishnah, a law code compiled in about 200 A.D. supplemented by the partly contemporaneous Tosefta;b the Talmud of the Land of Israel,c a systematic exegesis of the Mishnah, compiled about 400 A.D.; Midrashim (singular, Midrash), various collections of exe geses of Scriptures, compiled between 400 and 600 A.D.; biblical commentaries of the fourth and fifth centuries, such as Genesis Rabbah, Leviticus Rabbah and the Talmud of Babylonia, also a systematic explanation of the Mishnah, compiled about 500–600 A.D. All together, these writings 044constitute “the oral Torah,” that is, the body of tradition which, although originally oral, is nevertheless in principle assigned to the authority of God’s revelation to Moses at Mt. Sinai.d

The claim of these two great Western religious traditions, in all their rich variety, is the veracity not merely of Scripture, but also of Scripture as interpreted by the New Testament or by the oral Torah.

Thus, the Hebrew Scriptures produced two interrelated, yet quite separate, groups of religious societies that developed along lines established during late antiquity, culminating in the fourth century A.D.

As Christians looked to the figure of Christ, as reflected in the pages. of the New Testament, Jews looked to Torah as understood to include the rabbinic corpus. Torah means revelation: first, the five books of Moses; later, the whole Hebrew Scripture. But still later it referred to both the Written and Oral Revelation of Sinai, embodied in the Mishnah, the Talmuds and other rabbinical writings. Finally, Torah came to stand for, to symbolize, what in modern language is called “Judaism”: the whole body of belief, doctrine, practice, patterns of piety and behavior, and moral and intellectual commitments that constitute the Judaic version of reality.

While the Christ-event stands at the beginning the tradition of Christianity, the rabbinic corpus on the other hand, comes at the end of the formation of the Judaism that is contained within it. The rabbinic corpus is the written record of the constitution of the life of Israel, the Jewish people. The actual writing down of the rabbinic corpus occurred long after the principles and guidelines of that constitution had been worked out and effected in everyday life.

The early years of Christianity were dominated first by the figure of the Master, then his disciples and their followers, bringing the gospel to the nations. The formative years of rabbinic Judaism saw a small group of men who were not dominated by a single leader but who effected an equally far-reaching revolution in the life of the Jewish people.

Both the apostles and the rabbis thus reshaped the antecedent religion of Israel, and each in its own way claimed to be Israel. Initially, Christians sought their adherents from Jews. The Christian Jews proclaimed that the Messiah had come in Jesus. The rabbinic Jews proclaimed that only through the full realization of the imperatives of the Hebrew Scriptures, as interpreted and applied by the rabbis, would the people merit the coming of the Messiah. The rabbis, moreover, claimed that Moses had revealed not only the message now written down in his books, but also an oral Torah, that was formulated and transmitted to his successors, and they to theirs, through Joshua, the prophets, the sages, scribes and other holy men and, finally, to the rabbis of their day. For the Christian, therefore, the issue of the Messiah predominated; for the rabbinic Jew, the issue of Torah; and for both, as we shall see, the question of salvation became crucial.

Behind the immense varieties of Christian life stand the evocative teachings and theological and moral convictions assigned by Christian belief to the figure of Christ. To be a Christian in some measure meant, and means, to seek to be like him, in one of the many ways in which Christians envisaged him.

To be a Jew may similarly be reduced to the single, pervasive symbol of Judaism: Torah. To be a Jew meant to live the life of Torah, in one of the many ways in which the masters of Torah taught.

We now what the figure of Christ has meant to the art, music and literature of the West; the Church to its politics, history and piety; Christian faith to its values and ideals. It is harder to say what Torah would have meant to creative arts, the 045course of relations among nations and people, hopes and aspirations of ordinary folk, if it had come to predominate. For between Christ, universally known and triumphant, and Torah, the spiritual treasure of a tiny, harassed, abused people, seldom fully known and never long victorious, stands the abyss: mastery of the world on the one side, and that same world’s sacrifice on the other.

Perhaps the difference comes at the very start when the Christians, despite horrendous suffering, determined to conquer and save the world and to create the new Israel. The rabbis of Israel, unmolested and unimpeded, set forth to trans form and regenerate the old Israel. For the former, the arena of salvation was all humankind, actor was a single man. For the latter, the course of salvation began with Israel, God’s first love, the stage was that singular but paradigmatic society, the Jewish people.

To save the world the apostle had to suffer and for it, appear before magistrates, subvert empires. To redeem the Jewish people the rabbi had to enter into, share and reshape the life the community, deliberately eschew the politics nations and patiently submit to empires.

The vision of the apostle extended to all nations and peoples; immediate suffering therefore was the welcome penalty to be paid eventual universal dominion. The rabbi’s eye looked upon Israel, and, in his love for Jews, sought not to achieve domination or to risk martyrdom, but rather to labor for social spiritual transformation that was to be accomplished through the complete union of his life with that of the community. The one was prophet to the nations; the other, priest to the people. No wonder then that the apostle earned the crown of martyrdom, but prevailed in history; while rabbi received martyrdom, when it came, only as one of, and wholly within, his people. The rabbi gave up the world and its conversion in favor of his people and its regeneration. In the end people hoped that through its regeneration, need be through its suffering, the world would be redeemed. But the people would be instrument, not the craftsmen, of redemption, which God alone would bring.

That is how things look when we turn backward, from the present. But what do we see when we place ourselves squarely into the formative centuries of Christianity and of Judaism, the first four centuries of the Common Era? Let us look first at the religious world-view before 70 A.D., when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Jewish Temple. This is the world in which Jesus lived, the last common world shared by both traditions, Judaism and Christianity.

At the center of the Jewish world of the first century A.D. was Jerusalem and the Temple. From near and far pilgrims climbed the paths to Jerusalem. Distant lands sent their annual tribute, taxes imposed by a spiritual rather than a worldly sovereignty. Everywhere Jews turned to the Temple Mount when they prayed. Although Jews differed about matters of law and theology, the meaning history and the timing of the Messiah’s arrival, 046most affirmed the holiness of the city Isaiah called Ariel, Jerusalem, the faithful city. It was here that the sacred drama of the day must be enacted. And looking backward, we know they were right. It was indeed the fate of Jerusalem which in the end shaped the faith of Judaism and Christianity for endless generations to come—but not quite in the ways that most people expected before 70 A.D.

For centuries Israel had sung with the psalmist, “Pray for the peace of Jerusalem! May all prosper who seek your welfare!” (Psalm 122:6). Jews long contemplated the lessons of the old destruction of Jerusalem—by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. They were sure that by learning the lessons taught by the great prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel and (Second) Isaiah, they had ensured the city’s eternity.

Even then the Jews were a very old people. Their records, translated into the language of all civilized people (Greek), testified to their antiquity. They could look back upon ancient disasters, the spiritual lessons of which illumined current times.

In the Temple precincts, priests hurried to and fro, important because of their tribe, sacred because of their task, officiating at the sacrifices morning and eventide, busying themselves through the day with the Temple’s needs. In the Temple’s outer courts Jews from all parts of the world, speaking many languages, changed their foreign money for the Temple coin. They brought up their shekel, together with the free will, or peace, or sin, or other offerings they were liable to give. Outside, in the city beyond, artisans 047created the necessary vessels or repaired broken ones. Incense makers mixed spices. Animal dealers selected the most perfect beasts sacrifice. In the schools young priests were taught the ancient law, to which in time they would conform as had their ancestors before them, exactly as did their fathers that very day. All the population either directly or indirectly was engaged in some way in the work of the Temple. The city lived for it, by it and on its revenues. In modern terms, Jerusalem was a center of pilgrimage, and its economy was based upon tourism.

But no one saw things in such a light. Jerusalem had an industry, to be sure, but if a Jew were asked, “What is the business of this city?” he would have replied without guile, “It is a holy city, and its work is the service of God on high.” The Temple was the center of the world. To it, in time, would come the anointed of God. In the meantime, the Temple sacrifice was the way to serve God, a way he himself in remotest times had decreed. True, there were other ways believed to be more important, for the prophets had emphasized that sacrifice alone was not enough to reconcile the sinner to a God made angry by unethical or immoral behavior. Morality, ethics, humility, good faith—these, too, he required. But good faith meant loyalty to the covenant which had specified, among other things, that the priests do just what they were doing. The animal sacrifices, the incense, the oil, wine and bread were to be arrayed in the service of the Most High.

Later, people condemned this generation of the first Christian century. Christians and Jews alike reflected upon the Roman destruction of the great sanctuary in 70 A.D. They looked to the alleged misdeeds of those who lived at the time for reasons to account for the destruction. No generation in the history of Jewry had been so roundly, universally condemned by posterity.

Christians remembered, in the tradition of the Church, that Jesus wept over the city and said a bitter, sorrowing sentence:

“O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not! Behold, your house is forsaken and desolate. For I tell you, you will not see me again, until you say, ‘Blessed is the who comes in the name of the Lord’ ” (Matthew 23:37–39).

“And when the disciples pointed out the Temple buildings from a distance, he said to them, ‘You see all these, do you not? Truly, I say to you, there will not be left here one stone upon another, that will not be thrown down’ ” (Matthew 24:2; cf. Luke 21:6).

So for 20 centuries, Jerusalem was seen through the eye of Christian faith as a faithless city, killing prophets, and therefore desolated by the righteous act of a wrathful God.

But Jews said no less. From the time of Roman destruction, they prayed:

“On account of our sins we have been exiled from our land, and we have been removed far from our country. We cannot go up to appear and bow down before you, to carry out our duties in your chosen Sanctuary, in the great and holy house upon which your name was called” (Siddur, Musaf for the Sabbath that coincides with the new moon).

It is not a great step from “our sins” to “the sins of the generation in whose time the Temple was destroyed.” It is not a difficult conclusion, and more than a few have reached it. The Temple was destroyed mainly because of the sins of the Jews of that time, particularly, according to the tradition, the sin of “causeless hatred.” Whether the sins were those specified by Christians or by talmudic rabbis hardly matters. This was a sinning generation.

In fact, it was not a sinning generation, but one deeply faithful to the covenant and to the Scripture that set forth its terms, perhaps more so than many who have since condemned it. First-century Israelites sinned only by their failure. Had they overcome Rome, even in the circles of the rabbis they would have found high praise, for success reflects the will of Providence. On what grounds are they to be judged sinners? The Temple was destroyed, but it was destroyed because of a brave and courageous, if hopeless, war against the Romans. That war was waged not for the glory a king or for the aggrandizement of a people, but in the hope that at its successful conclusion, pagan rule would be extirpated from the holy land. This was the articulated motive of the Jewish revolt that began in 66 A.D. It was a war fought explicitly for the sake of, and in the name of, God. The struggle called forth prophets and holy men, whom the people courageously followed past all hope of success. The Jews were not demoralized or cowardly, afraid to die because they had no faith in what they were doing. The 048Jerusalemites fought with amazing courage, despite unbelievable odds. Since they lost, later generations looked for their sin, for none could believe that the omnipotent God would permit his Temple to be destroyed for no reason. As after 586 B.C., so after 70 A.D., the alternative was this, we might imagine the words of the time: “Either our fathers greatly sinned, or God is not just.” The choice thus represented no choice at all.

“God is just; we have sinned—we, yes, but mostly our fathers before us. That is why all this has come upon us—the famine, the exile, the slavery to pagans—these are just recompense for our own deeds.”

During the period just before the destruction of the Temple, the period when Jesus lived, there was no such thing as “normative Judaism” from which one or another “heretical” group might diverge. Not only in the great center of the faith, Jerusalem, do we find numerous competing groups, but throughout the country and abroad we may discern a religious tradition in the midst of great flux. It was full of vitality, but in the end without a clear and widely accepted view of what was required of each individual, apart from acceptance of Mosaic revelation. And this could mean whatever you wanted. People would ask one teacher after another, “What must I do to enter the kingdom of heaven?” precisely because no authoritative answer existed.

In the period before the Roman destruction of the Temple, some Jews withdrew completely. The monastic commune at Qumran near the shores of the Dead Sea where the famous scrolls were found was one such group. To the barren heights overlooking the barren Rift Valley came people seeking purity and hoping for eternity. The purity they sought was not from common dirt, but from the uncleanness of this world. In their minds, this age was impure and therefore would soon be coming to an end. Those who wanted to do the Lord’s service should prepare themselves for a holy war at the end of time. Men and women came to Qumran with their property, which they contributed to the common fund. There they prepared for a fateful day, not too long to be postponed, scarcely looking backward at those remaining in the corruption of this world. These Jews would be the last, smallest, “saving remnant” of all. Yet, through them, all humankind would come to know the truth. Strikingly, they held that God himself had revealed to Moses the very laws they now obeyed.

Pharisees, probably meaning Separatists, also believed that all was not in order with the world. But they chose another way, likewise attributed to Mosaic legislation. They remained within the common society in accordance with the teaching of their leading sage Hillel: “Do not separate yourself from the community.” The Pharisaic community therefore sought to rebuild society on its own ruins with its own mortar and brick. The Pharisees actively fostered their opinions on tradition and religion among the whole people. According to the first-century Jewish historian Josephus, the Pharisees “are able greatly to influence the masses of people. Whatever the people do about divine worship, prayers, and sacrifices, they perform according to their direction. The cities give great praise to them on account of their virtuous conduct, both in the actions of their lives and their teachings also” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 13:171–173).

Though Josephus exaggerated the extent of their power, the Pharisees certainly exerted considerable influence in the religious life of Israel before they finally came to power in 70 A.D.

Among those sympathetic to the Pharisaic cause were some who entered into an urban religious communion, a mostly unorganized society known as the fellowship (havurah). The basis of this society was meticulous observance of laws of tithing and other priestly offerings, as well as the rules of ritual purity outside the Temple where the observance of such laws was not mandatory. Even profane foods (not sacred tithes or other offerings) the members undertook to eat in a state of rigorous levitical cleanness. At table, they compared themselves to Temple priests at the altar. These rules tended to segregate the members of the fellowship, for they ate only with those who kept the law as they thought proper. The fellows thus mediated between the obligation to observe religious precepts and the injunction to remain within the common society. By keeping the rules of purity, the fellow separated from the common man, but by remaining within the towns and cities of the land, he preserved the possibility of teaching others by example.

Upper-class opinion was expressed in the viewpoint of still another group, the Sadducees. They stood for strict adherence to the written word in religious matters, conservatism in both ritual and belief. Their name probably derived from the priesthood of Zaddoq, established by King David ten centuries earlier. They acknowledged Scripture as the only authority, themselves 049as its sole arbiters. They denied that its meaning might be elucidated by the Pharisees’ allegedly ancient oral traditions attributed to Moses or by the Pharisaic devices of exegesis and scholarship. The Pharisees claimed that Scripture and the traditional oral interpretation were one. To the Sadducees, such a claim of unity was spurious and masked innovation. The two factions differed also on the eternity of the soul. The Pharisees believed in the survival of the soul, the revival of the body, the day of judgment and life in the world to come. The Sadducees found nothing in Scripture that to their way of thinking supported such doctrines. They ridiculed both these ideas and the exegesis that made them possible. They won over the main body of officiating priests and wealthier men. With the destruction of the Temple their ranks were, however, decimated. Very little literature later remained to preserve their viewpoint. In their day, however, the Sadducees claimed to be the legitimate heirs of Israel’s faith. Holding positions of power and authority, they succeeded in leaving so deep an impression on society that even their Pharisaic, Essenian and Christian opponents did not wholly wipe out their memory.

The Sadducees were most influential among land holders and merchants, the Pharisees among the middle and lower urban classes, the Essenes among the disenchanted of both these classes. These classes and sectarian divisions manifested a vigorous inner life, with politics revolving about peculiarly Jewish issues such as matters of exegesis, law, doctrine and the meaning of history. The vitality of Israel would have astonished the Roman administration, and when it burst forth, it did.

The rich variety of Jewish religious expression in this period ought not to obscure the fact that for much of Jewish Palestine, Judaism was a relatively new phenomenon. Herod, who was of Idumean stock, was the grandson of pagans. Similarly, the entire Galilee had been converted to Judaism only 120 years before the Common Era. In the later expansion of the Hasmonean kingdom that preceded Herod’s rule, outlying regions were forcibly brought within the Jewish fold. The Hasmoneans used Judaism imperially, as a means of winning the loyalty of the pagan Semites in the regions of Palestine they conquered. But in a brief period of three or four generations the deeply rooted pagan practices of the Semitic natives of Galilee, ldumea and other areas could not have been wiped out. They were rather covered over with a veneer of monotheism. Hence the newly converted territories, though vigorously loyal to their new faith, were no more Judaized in so short a time than were the later Russians, Poles, Celts or Saxons Christianized within a century. It took a great effort to transform an act of circumcision of the flesh, joined with a mere verbal affirmation of one God, made under severe duress, into a deepening commitment of faith. Only after many generations was the full implication of conversion realized in the lives of the people in Galilee, and then mainly because great centers of tannaitic lawe and teaching had been established among them.

In the end, two groups emerged—the Christians and the rabbis, the latter the heirs of the Pharisaic sages. Each offered an all-encompassing interpretation of Scripture, explaining what it did and did not mean. Each promised salvation for individuals and for Israel as a whole.

Of the two, the rabbis achieved somewhat greater success among the Jews. Wherever the rabbis’ view of Scripture was propagated, the Christian view of the meaning of biblical, especially prophetic, revelation and its fulfillment, made relatively little progress. This was true, not only in Jewish Palestine itself, but in certain cities in Mesopotamia, and in central Babylonia. Where the rabbis were not to be found, as in Egyptian Alexandria, Syria, Asia Minor, Greece and in the West, Christian biblical interpretation and salvation through Christ risen from the dead found a ready audience among the Jews. It was not without good reason that the gospel tradition of Matthew saw in the “scribes and Pharisees” the chief opponents of Jesus’ ministry. Whatever the historical facts of that ministry, the rabbis proved afterward to be the greatest stumbling block for the Christian mission to the Jews.

Christianity was born in a world of irrepressible conflict. That conflict was between two pieties, two universal conceptions of what the world 050required. On the one hand, the Roman imperialist thought that good government, that is, Roman government, must serve to keep the peace. Rome would bring the blessings of civil order and material progress to many lands. For the Roman, that particular stretch of hills, farmland and desert the Jews called “the Land of Israel” meant little economically, but a great deal strategically. No wealth could be hoped from it, but to lose Palestine would mean to lose the keystone of empire in the East. We see Palestine from the perspective of the West. It appears as a land bridge between Egypt and Asia Minor, the corner of a major trade route. But to the Roman imperial strategist, Palestine loomed as the bulwark of the eastern frontier against Parthia. The Parthians, holding the Tigris-Euphrates frontier, were a mere few hundred miles from Palestine, separated by a desert no one could control. If the Parthians could take Palestine, Egypt would fall into their hands. Parthian armies moreover were pointed like a sword toward Antioch and the seat of empire established there. Less than a century earlier they had actually captured Jerusalem and seated upon its throne a puppet of their own. For a time they thrust Roman rule out of the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

For Rome therefore, Palestine was too close to the most dangerous frontier of all to be given up. Indeed, among all the Roman frontiers only the Oriental one was, now contested by a civilized and dangerous foe. Palestine lay behind the very lines upon which that enemy had to be met Rome could ill afford such a loss. Egypt, moreover, was Rome’s granary, the foundation of her social welfare and wealth. The grain of Egypt sustained the masses of Rome itself. Economic and military considerations thus absolutely required the retention of Palestine. Had Palestine stood in a less strategic locale, matters might have been different. Rome had a second such frontier territory to consider—Armenia. While she fought vigorously to retain predominance over the northern gateway to the Middle East, she generally remained willing to compromise on joint suzerainty with Parthia in Armenia—but not in Palestine.

For the Jews, the Land of Israel meant something of even greater import. They believed that history depended upon what happened in the Land of Israel. They thought that from creation to the end of time, the events that took place in Jerusalem would shape the fate of all humankind. Theirs, no less than Rome’s, was an imperial view of the world, but with this difference: The empire was God’s. If Rome could not lose Palestine, the Jews were likewise unwilling to give up the Land of Israel. Rome scrupulously would do everything possible to please Jewry, permitting the Jews to keep their laws in exchange only for peaceful acquiescence to Roman rule. There was, alas, nothing Rome could actually do to please the Jews but evacuate Palestine. No amiable tolerance of local custom could suffice to win the people’s submission.

These two imperialisms confronted each other in a war known as the First Jewish Revolt, which erupted in 66 A.D. and ended in 70 A.D. with the destruction of Jerusalem and the burning of the Jewish Temple. Sixty years later, in 132 A.D., the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome, led by Bar Kokhba, began. In 135 A.D. that revolt ended, much as the earlier one had. This time, however, Jews were expelled from Jerusalem, and the city was rebuilt by Hadrian as a new Roman town named Aelia Capitolina.

In the mind of many, the destruction that ended the first revolt set in motion the expectations that led to the second. When the Temple was destroyed in 70 A.D., Jews naturally looked to Scripture to find the meaning of what had happened and, more important, to learn what to expect. There they discovered that when the Temple had been previously destroyed (in 586 B.C.), a period of three generations—about 70 years—intervened before its rebuilding began. After three generations, and in the aftermath of atonement and reconciliation with God, Israel was restored to its land, the Temple to Jerusalem and the priests to the service of the altar. Thus, many surmised, in three generations the same pattern would be reenacted after the Roman destruction, now with the Messiah at the head of the restoration. So people waited patiently and hopefully.

But whether Bar Kokhba said he was the Messiah (as some say), or not, he was to disappoint the hopes placed in him. The Jews, possessed of a mighty military tradition then as now, fought courageously, but lost against overwhelming force. In the aftermath, except on special occasions, Jerusalem was closed to the Jews. Jewish settlement in the southern part of the country was to a large extent wiped out. A deep disappointment settled over the people after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome.

51

The Judaism that took shape after the failure of the Second Jewish Revolt was a direct and immediate response to the momentous events of the day. In many ways Judaism, from age to age, forms God’s commentary on the history of the Jewish people; the holy books of Judaism contain, that commentary. So too in the history of Judaism from the first to the fourth century of the Common Era.

Of those books, the first and most important, the foundation for all else, the basis for Judaism from then to now, is the Mishnah.

The Mishnah is a work of philosophy expressed through laws. It is a set of rules, phrased in the present tense: “One does this, one does not do that.” But when we look closely at the issues worked out by those laws, time and again we find profound essays on philosophical questions, like being and becoming, the acorn and the oak, the potential and the actual.

The topical program of the document—as distinct from the deep issues worked out through discussion of the topics—focuses upon the sanctification of the life of Israel, the Jewish people. Four of the six principal parts of the Mishnah deal with the cult and its officers, although the Temple had been destroyed. These are, first, Holy Things, which addresses the everyday conduct of the sacrificial cult; second, Purities, which takes up the protection of the cult from sources of uncleanness specified in the Book of Leviticus (particularly Leviticus 12–15); third, Agriculture, which centers on the designation of portions of the crop for the use of the priesthood (and others in the classification of a holy caste, such as the poor), and so provides for the support of the Temple staff; and, fourth, Appointed Times, the larger part of which concerns the conduct the cult on such special occasions as the Day Atonement, Passover, Tabernacles and the like.

The two remaining divisions of the Mishnah deal with everyday affairs—one, Damages, concerns civil law and government; the other, Women, takes up issues of family, home and personal status. That, sum and substance, is the program of the Mishnah.

The Mishnah was completed in written form around the year 200, approximately two long generations after the defeat of Bar Kokhba’s armies. It lasted and proved influential because it served as the basic law book of the Jewish government in the Land of Israel, of the authority of the Jewish patriarchate and of the minority government of the Jews in Babylonia. Babylonia allowed its many diverse ethnic groups to run their own internal affairs, and the Jewish regime, led by the “head of the exile,” or exilarchate, employed sages who had mastered the Mishnah and imposed the pertinent laws of the Mishnah within its administration and courts. So the 052Mishnah rapidly became not a work of speculative philosophy, in the form of legal propositions or rules, but a law code for the concrete and practical administration of the Jewish people in its autonomous life.

The Mishnah says little, however, about what happened in the century before it was completed. There are a few episodic allusions to the destruction of the Temple and to the repression after the war of 132–135, but not many. If we were to ask the compilers of the Mishnah to give us their comment on that double catastrophe they would direct us not to the bits and pieces, but to the document as a whole; that is Israel’s response. The Mishnah focuses upon the sanctification of Israel, the Jewish people; its message is that the life of the people, like the life of the cult, bears the marks of holiness. That is its response to the failure of the two revolts against the might of Rome.

Let me give an example:

The law of the Mishnah repeatedly uses the language of sanctification when it speaks of the relationship between man and woman, and it regards marriage as a critical dimension of the holiness of Israel, the Jewish people. Building on the scriptural rules, the sages point to the holiness of the marital bed, conducted as it is in accord with the laws of Leviticus 15. The woman is holy to the man, and the man to the woman. The union between the two is sanctified under God’s rule. Their table, where foods are served that accord with the levitical requirements (for example, of Leviticus 11), is holy. The rhythm of time and circumstance is holy, as a holy day comes to the home and transforms the home into the model of the Temple.

In all these ways, the message of the Mishnah comes through: The holy Temple is destroyed, but holy Israel endures, and will endure until, in God’s time, the holy Temple is restored. That focus upon sanctification therefore imparts to the Mishnah remarkable relevance to the question on peoples’ minds: If we have lost the Temple, have we also lost our tie to God? No, the Mishnah’s authors reply, Israel remains God’s holy people. The Mishnah then outlines the many areas of sanctification that endure in agriculture, in appointed times and in the record of the Temple, studied and restudied in the mind’s reenactment of the cult.

But, as we shall see, the Mishnah stressed sanctification, to the near-omission of the other critical dimension of Israel’s existence, salvation. Only later on would Scripture exegetes complete the structure of Judaism, a system resting on the twin foundations of sanctification in this world and salvation in time to come.

The sages eventually came to believe that the Mishnah formed, part of the Torah, God’s will for Israel revealed to Moses at Sinai. Originally not a work of religion in a narrow sense, the Mishnah in the end attained the status of revelation. The first great explanation of the authority of the Mishnah (from the third century) the Sayings of the Fathers (Pirqé Avot) tells us that “Moses received Torah on Sinai and handed it on to Joshua,” and the chain of tradition goes on. The latest in the list turns out to be authorities named in the Mishnah itself. So what these authorities taught, they received in a chain of tradition from Sinai. What they taught was Torah.

Such a claim imparted to the Mishnah and its teachers a position in the heart and mind of Israel, the Jewish people, that would ensure its long-term influence. Between 200 and 400, when the first Talmud the one of the Land of Israel, was redacted, the Mishnah was extensively studied, line by line, word by word. So the sages who were responsible for administering the law also expounded and expanded it. Ultimately, the work of Mishnah commentary developed into the Talmud. In fact there were two large-scale documents, each called a Talmud. One developed in Palestine, called the Talmud of the Land of Israel, completed by about 400 A.D., and the other, the Talmud of Babylonia, completed by about 600 A.D.

In addition to the kind of Mishnah commentary that produced the Talmuds, another process took place side by side with it. This latter process drew attention back to Scripture. The Mishnah only occasionally adduces scriptural texts in support of its rules. In the centuries after the codification of the Mishnah, the question arose as to the relationship between law and Scripture. Could the law be discovered through sheer logic? Or must we tease laws out of Scripture through commentary, through legal exegesis, as it were?

The Mishnah represented one extreme in this debate. Much of the law enunciated in it does not derive from Scripture. Even when there are pertinent scriptural texts, these texts are not cited.

053

In the Sayings of the Fathers (Pirqé Avot—third century) where the chain of authority from Mt. Sinai to the sages is traced, the sages named in the Mishnah do not cite verses of Scripture (except in one or two instances). They teach sayings of their own. So the sages of the Mishnah seem to enjoy an independent standing and authority on their own; they are not subordinate to Scripture, their sayings appear to enjoy equal standing with saying of Scripture.

But side by side with this development, other learned Jews were confirming the relationship between law and Scripture. Important works of biblical commentary emerged in the third and fourth centuries that inferentially addressed this issue. The form these commentaries took is essentially this: From such-and-such statement in Scripture, we may draw the following rule of the Mishnah. In this way, the sages sought to build bridges from the Mishnah to Scripture. In doing so, they vastly articulated the theme of the Mishnah, the sanctification of Israel.

Sanctification, after all, is not salvation. Judaism, like Christianity, offered salvation too. Where, when and how did the sages who were reshaping Judaism address that complementary category of Israel’s existence, salvation?

Complementary to their effort to derive from Scripture the laws of the Mishnah, the sages also sought to derive from Scripture the laws of history, and particularly of Israel’s history. In the context of this effort, they confronted the issues of salvation and of Israel’s relationship to God. These are the issues the sages deal with in Genesis Rabbah (literally the expansion of Genesis) and Leviticus Rabbah, products, as we shall see, of crucial time—the fourth century.

The impetus for works like Genesis Rabbah and Leviticus Rabbah came, I believe, from Christianity. These works reached redacted form in the fifth century but were a product of the fourth century, the century of Christianity’s political triumph. The emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in 313, and his successors declared Christianity the religion of the empire. The historical crisis precipitated by Christianity’s takeover of the Roman empire and its government demanded answers from Israel’s sages: What does it mean? What does history mean? Where are we to find guidance to the meaning of our past—and our future? The sages looked to Genesis, explaining that the story of the creation of the world and the beginning of Israel would light the way toward the meaning of history and Israel’s salvation. In Leviticus Rabbah, the sages linked the sanctification of Israel through cult and its priesthood, which is the theme of the Book of Leviticus, to the salvation of Israel.

The message was complete: Sanctifying the life of Israel now will lead to the salvation of Israel in time to come; sanctification and salvation, the natural world and the supernatural, the rules of society and the rules history all become one in the life of Israel.

Just as the Mishnah was a response to the destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. and the confirmation of that destruction reflected in the suppression of the Second Jewish Revolt in 135 A.D., so Genesis Rabbah and Leviticus Rabbah were responses to historical crises for Judaism just as critical and perplexing as the crises of 70 and 135. When Constantine declared Christianity a legal religion in 313: A.D., then favored the Church, and finally converted to Christianity, when his heirs and successors made Christianity the religion of the Roman empire, the sages of Israel were faced with a new crisis. The crisis was not so much political and legal, though it bore deep consequences in both politics and the Jews’ standing, in law; but its most formidable dimension was spiritual. If the Messiah was yet to come, then why did Jesus, enthroned as Christ, now rule the world? Christians asked Israel that question, but, of greater consequence, Israel asked itself.

One other event of the fourth century deepened the Jewish spiritual crisis. In 361 A.D. Julian, a pagan, ascended the Roman throne and immediately turned the empire away from Christianity. Moreover, he invited the Jews to rebuild their Temple, raising anew Jewish messianic hopes and aspirations. But Julian was killed in 363. The project of rebuilding the Temple died aborning. The succeeding emperors, Christians all, restored the throne to Christ (as they would put it) and secured for the Church and Christianity the control of the State through law. The destruction of the Temple in 70 A.D. now proved definitive, as the fourth-century Church Father John Chrysostom argued, in the aftermath of Julian’s brief reign. According to Jewish tradition, the Temple was supposed to be rebuilt 300 years after its destruction, but God prevented it. What hope for Israel now—or ever? What meaning for Israel in history now—or at the end of time?

054

The Jewish response was to turn back to—and reinterpret—Scripture: First, Genesis, on the creation of the world and of the Children of Israel; second, Leviticus, on the sanctification of Israel. The sages explained history by rereading Scripture. There they found the lesson: What happened to the patriarchs in the beginning tells us what would happen to our children. Jacob then is Israel now, just as Esau becomes a symbolic representation of Rome. What happened to Esau will happen to Rome. And Israel remains: the bearer of the blessing.

It is at this time that we find the first clear reference to the notion that when God revealed the Torah to Moses at Sinai, only part of the Torah was in writing, the other part being given orally. Still later it would be explained that the Mishnah and its progeny enjoyed the status of oral Torah.

Genesis Rabbah and Leviticus Rabbah explain the Messiah-claim of Israel in very simple terms. Israel indeed will receive the Messiah, but salvation at the end of time awaits the sanctification of Israel in the here and now. And that will take place through humble and obedient loyalty to the Torah. These books counter the claim that there is a new Israel in place of the old. Leviticus Rabbah rereads and reinterprets the Book of Leviticus, with its message of sanctification of Israel, and finds in it a typology of the great empires—Babylonia, Media, Greece, Rome. The fifth, and final, sovereign will be Israel’s messiah.

In this way, the fourth-century sages countered the claims implicit in the triumph of Constantine’s Christian empire—and explicit in the teaching of the Church—that history vindicates Christ, that the New Testament explains the Old, that the Messiah has come; that his claim has now been proven truthful; and that the Old Israel is done for and will not have a messiah in the future.

Interestingly enough, the Jewish claim that a dual Torah (one written and one oral) was given at Sinai, and the stress on the messianic dimension of Israel’s everyday life, as well as the permanence of Israel’s position as God’s first love, is not to be found in the Mishnah or the other rabbinical works of the third century. Instead, it finds its first articulate expression in the writings of the fourth century, in the Talmud of the Land of Israel as well as in Genesis Rabbah and Leviticus Rabbah. The reason why all this did not appear until the fourth century is simple: This Jewish system in the fourth century was responding to a competing system—the Christian system. The Jewish system, heir to the ancient Israelite Scriptures was answering another heir to these Scriptures and its claims. The siblings would struggle, like Esau and Jacob, for the common blessing. For the Jewish people, the system of the fourth-century sages would endure for millennia as self-evidently right and persuasive.

Jews and Christians alike believed in the Israelite Scriptures, and therefore understood that major turnings in history carried a message from God. That message bore meaning for questions of salvation and the Messiah, for the identification of God’s will in Scripture, for the determination of who is Israel, and for what it means to be Israel, and for similar, questions of a profoundly historical and social character. So it is no wonder that the enormous turning represented by the advent of a Christian empire should have precipitated deep thought on these issues.

Prior to the time of Constantine, the documents of Judaism that evidently reached closure—the Mishnah, Pirqé Avot, the Tosefta—scarcely took cognizance of Christianity and did not deem the new faith to be much of a challenge. If the scarce and scattered allusions do mean to refer to Christianity (a debated matter), then the sages regarded it only as an irritant, an exasperating heresy among Jews who should have known better. But, then, neither Jews nor pagans took much interest in Christianity during the new faith’s first century and a half. The authors of the Mishnah framed a system to which Christianity bore no relevance whatsoever; theirs were problems presented in an altogether different context. For their part, pagan writers were also indifferent to Christianity, not mentioning it until about 160. Only when Christian evangelism enjoyed some solid success, toward the later part of that century, did pagans compose apologetic works attacking Christianity. Celsus stands at the start, followed by Porphyry in the third century. But by the fourth century, pagans and Jews alike knew that they faced a formidable, powerful enemy. Pagan writings speak explicitly and accessibly. The answers the Jewish sages worked out to respond to the intellectual challenge of the hour do not emerge equally explicitly and accessibly. But they 055are there, and, when we ask the right questions and establish the context of discourse, we hear the answers in the Talmud of the Land of Israel, in Genesis Rabbah and in Leviticus Rabbah, as clearly as we hear pagans’ answers in the writings Porphyry and Julian, not to mention the Christians’ answers in the rich and diverse writings of the fourth-century fathers, such as Eusebius, Jerome, John Chrysostom and Aphrahat, to mention just four. In truth, as Rosemary Radford Reuther pointed out nearly 15 years ago, the fourth century was the first century of both Christianity and Judaism as the West would know them for the next 1, 500 years.f

This is not to suggest that only these topics dominated the sages’ thought and the consequent shape of their writings. I do not claim that all of Genesis Rabbah deals with the meaning of history, though much of it does; that all of the Talmud of the Land of Israel takes up the messianic question, though important components do; or that all of Leviticus Rabbah asks about who is Israel, though the question is there. None, indeed, can assess matters of proportion, importance or, therefore, predominance, in so sizable a corpus as that of the sages before us. Characterizing so large and complex a corpus of writings as theirs poses problems of its own. We cannot readily settle to everyone’s satisfaction the questions of taste and judgment involved in determination of proportion and identification of points of stress. Just as the formative figures of Christianity had more on their minds than the issues I lay out, so the creative and authoritative intellects of Judaism thought about many more things than those I take up.g But that is not the point The point is simple. The topics, dictated by politics, did matter, and both sides did confront them.

For the first time, Judaism and Christianity in the fourth century confronted each other in a way that defined that confrontation for the next 1, 500 years. In the first century, it was different Christians and Jews then did not argue with one another. Christianity and Judaism went their separate ways, each focusing on its own program. In the first century, one important strand of the Christian movement laid stress on issues of salvation, maintaining in the Gospels that Jesus was, and is, Christ, come to save the world and impose radical change on history. At that same time, an important group within Judaism, the Pharisees, emphasized issues of sanctification, maintaining that the task of Israel is to attain that holiness of which the Temple was a singular embodiment When, in the Gospels, we find the Church placing Jesus into opposition with the Pharisees, we witness the confrontation of different people talking about different things to different people.

In the fourth century, by contrast different people addressing different groups really did talk about exactly the same things. That is the point, therefore, at which the Judaic and Christian conflict reached the form in which, for 1, 500 years, it would come to intellectual expression. People really did differ about the same issues. These issues—the meaning of history, the identity of the Messiah and the definition of Israel, or of God’s instrument for embodying in a social group God’s will—would define the foundations of the dispute from the fourth century on.

The ancient rabbis, as we have seen, looked out upon a world destroyed and still smoking in the aftermath of calamity, but they speak of rebirth and renewal. The holy Temple lay in ruins, but they ask about sanctification. The old history was over, but they look forward to future history. Their message is that what is true and real is the opposite of what people perceive. God stands for paradox. Strength comes through weakness; salvation, through acceptance and obedience; sanctification, through the ordinary and profane, which can be made holy.

To informed Christians, this mode of thought must prove remarkably familiar: For the cross that stands for weakness yields salvation; and the crucified criminal is king and savior. That is the “foolishness” to which the apostle Paul makes reference. Yet the greater the “nonsense”—life out of the grave, eternity from death—the deeper the truth, the richer the paradox!

So here we have these two groups of old Jews—one group speaking of the sanctification of Israel the people; the other, of the salvation of Israel and the world. Separately, they are thinking along the same lines, coming to conclusions remarkably congruent to one another—in the rabbinical framework, affirming the paradox of God in this world, and of humanity in God’s image; in the Christian, of God in the flesh.

Everyone knows that Judaism gave birth to Christianity. But the formative centuries of Christianity also tell us much about the development of Judaism. As formative Christianity demands to be studied in the setting of formative Judaism, so formative Judaism must be studied in the context of formative Christianity. Both Judaism and Christianity rightly claim to be the heirs and products of the Hebrew Scriptures—Tanakha to the Jews, Old Testament to the Christians. Yet both great religious tradition derive not solely or directly from the authority and teachings of those Scriptures. They reach us, rather, from the ways in which […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

The Tosefta was redacted around 400 A.D. (we have no exact knowledge). The document encompassed three types of teachings. First, it contained direct citations of statements in the Mishnah, which were then glossed or expanded. Second, it included statements that related to, but did not cite verbatim, statements in the Mishnah. These versions of rules cannot be fully understood without referring to their counterparts in the Mishnah. Finally, it presented statements that are entirely autonomous, in theme or in principle or in detail, of anything in the Mishnah. The first two types of materials depend upon, therefore are later than, the Mishnah itself. The third type can derive from the same period as the Mishnah. That type is quite small in proportion to the whole, certainly not more than 20 percent overall.

Also known as the Yerushalmi or Jerusalem Talmud. It is also referred to as the Palestinian Talmud.

There are a number of other books in the rabbinic corpus—for example, Sifrei to Deuteronomy, Sifrei to Numbers, Sifra to Leviticus, Pesikta de-Rav Kahana—but I limit myself in this article to those books which are most relevant to my thesis relating to the parallel development of Judaism and Christianity. Other books of the rabbinic corpus responded to other issues and agendas relating for the most part to concerns internal to Judaism.

The Tanna was a sage who memorized and repeated a teaching of the Mishnah. The word tny corresponds to the Hebrew word for repeat, sny. Tannaim, therefore, preserved Mishnah teachings both before the editing of the Mishnah in about 200 A.D. and afterward.