Digging in the City of David

Jerusalem’s new archaeological project yields first season’s results

036

037

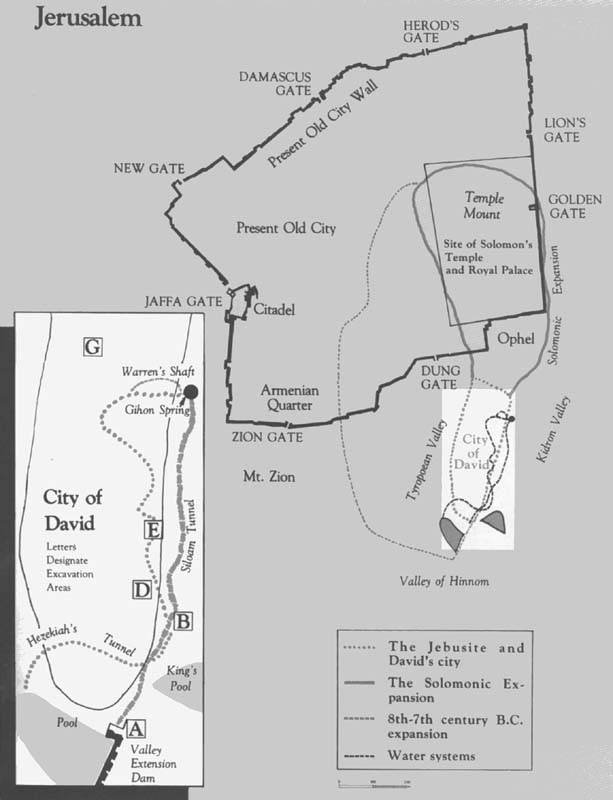

Our first season of excavations in the City of David—the site of Biblical Jerusalem—ended with rich rewards and high expectations. The City of David, in geographical terms, is only a very small part of modern Jerusalem—a little spur which, to the surprise of many tourists, is located outside the walls of the Old City. To the archaeologist and historian, the City of David is the area occupied by Jerusalem in the Canaanite and Israelite periods, including the time of David (c. 1000 B.C.) 038Projecting from the eastern half of the southern wall of the Old City, the City of David stretches south of the Temple Mount, east of Mt. Zion and west of the Kidron Valley.

The City of David lies at the core of ancient Jerusalem because it is adjacent to the main water source, the Gihon Spring. The first settlement goes back to the beginning of the Early Bronze Age (about 3000 B.C.). Only in the City of David is it possible—depending, of course, on the state of underground preservation—to unearth occupational remains of the Canaanite and early Israelite cities of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages.

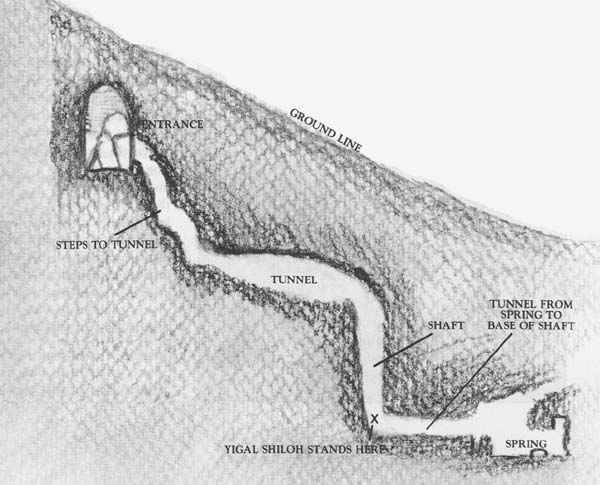

Ancient Jerusalem has been a target of exploration and excavation for over one hundred years. In 1838, for the first time in modern days, the American orientalist Edward Robinson traversed Hezekiah’s Tunnel which runs underneath the City of David. In 1865 Charles Wilson began his landmark survey of old Jerusalem on behalf of England’s Palestine Exploration Fund. Charles Warren joined Wilson between 1867–70 and investigated many sites in and around the Old City, including—in the City of David—the oldest underground water system, known today as “Warren’s Shaft.”. This water system was reexamined by Montague Parker (1909–1911). In the years that followed, other more respectable scholars explored and excavated the site of David’s City. The Englishmen Frederick J. Bliss and Archibald C. Dickie investigated the course of southern Jerusalem’s walls between 1894 and 1897. The French diplomat and scholar Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1873), the German Hermann Guthe (1881), the Frenchman Raymond Weill (financed by the Rothschilds) (1913–14 and 1923–24), the Irishman R. A. S. Macalister (1923–25), and the Englishmen John W. Crowfoot and Gerald M. Fitzgerald (1927–28) all excavated and examined various segments of ancient Jerusalem’s fortification-wall system during different periods of the city’s long history.

A new chapter in City of David research began in 1961–67 with the excavations of Kathleen Kenyon. For the first time, this area of Jerusalem was the subject of a controlled excavation employing up-to-date archaeological methods—many years after other Biblical sites throughout Israel had been excavated by modern methods. The Kenyon excavations yielded a wealth of information from the Bronze and Iron Ages, third to first millennium B.C. Dame Kathleen’s death last August may, unfortunately, seriously delay the publication of her results.

One of the most important conclusions of her work is that the fortification wall-lines of the Bronze and Iron Ages (Canaanite and Israelite Jerusalem) lay much further down the eastern slope of the ridge than previous investigators had thought. Between this lower line and the crest of the hill (where Hellenistic-Roman fortification walls have been found) is an area whose pre-Second Temple buildings may have been untouched by later building operations. This area between the lower and higher defense lines was obviously tempting to excavate.

Although ancient Jerusalem became available to Israeli archaeologists in 1967, The City of David waited more than a decade to receive archaeological attention. It was no accident that this was the last site in Jerusalem to be investigated, for many scholars 039seriously doubted whether there were any significant remains yet to be uncovered. Dame Kathleen put the matter succinctly after her own excavations in the City of David. “I believe that our excavations have produced a plan of earliest Jerusalem that can only be disproved if further excavations produce more factual (by which I mean stratigraphical) evidence. I do not believe that opportunities for such excavations survive, mainly because of ancient quarryings, but also modern building activities. If they do, I wish the excavators luck.” (We appreciated Dame Kathleen’s good wishes, but we also confess to having been a bit frightened by her skepticism. We had no choice, however, but to be optimistic.)

After the Six-Day War in June 1967, widespread reconstruction and development projects were undertaken in various parts of both the Old City and modern Jerusalem. The reconstruction project in the Old City compelled immediate archaeological excavations there in order to plan the reconstruction of the Old City’s destroyed buildings. Another high priority project was the creation of an archaeological garden surrounding the Old City walls. Eventually, this archaeological garden will encompass additional areas in the Jewish Quarter, Mt. Zion, and the City of David itself. These post-1967 excavations have given us a wealth of new information about the history of Jerusalem from the late First Temple, Second Temple, late Roman, Byzantine, Islamic, Crusader, and Turkish periods. Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology was the major partner in two large-scale excavations, one around the Temple Mount led by Professor Benjamin Mazar, and the other in the Jewish Quarter led by Professor Nachman Avigad. Other excavations were conducted in the Armenian Quarter, on Mount Zion, and at the Jaffa Gate citadel.

In 1977, after ten years of constant work, the Temple Mount Excavations began to wind down, and the Institute of Archaeology began to plan the last and most difficult campaign in Jerusalem—renewed excavation in the City of David. Large-scale excavations were clearly required, yet whether the results would be worth the effort required was very doubtful, because the City of David had already been explored and excavated more than any other Biblical site. Moreover, for a time it seemed as though there was neither staff nor money to undertake the work.

With the help of Teddy Kollek, Mayor of Jerusalem and a master matchmaker, a meeting was arranged in the offices of the Jerusalem Foundation, at which we agreed to organize “The City of David Society for the Excavation, Preservation and Restoration of the City of David, Jerusalem.” The president of the Society is the mayor of Jerusalem. Its members include the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Israel Exploration Society, the Jerusalem Foundation, and the group of South African sponsors headed by Mendel Kaplan. Yigal Shiloh was formally appointed director of the archaeological project.

Despite one hundred years of exploration, much remains unknown about Jerusalem’s early history. As we made plans for our excavations, we formulated historical archaeological questions which we hoped our excavation would answer.

What can be learned about Jebusite Jerusalem before it was conquered by the Israelites?

How was the city culturally transformed when it was captured from the Canaanites and made the capital of the united kingdom of Judah and Israel?

What will we learn about the massive construction in Jerusalem which occurred during the reigns of King Solomon and King Hezekiah?

How were the underground water systems of the First Temple period related to one another and to the plan of the city?

What were the borders of the city during the various sub-periods of the Iron Age?

What happened when the City of David was reconstructed during the Persian period?

Will we find new evidence from the Hellenistic period in our excavation?

Will we learn something about Jerusalem when it became the capital of the Hasmonean Kingdom?

Can we document that the City of David was a springboard for the extension of the city northward and westward beginning in King Solomon’s time, continuing during King Hezekiah’s reign, and reaching its peak in the period just before the First Jewish Revolt against Rome in 66 A.D.?

We also contended with the practical difficulties of putting together the expedition. Unlike an abandoned tell in the Judean hills or the Negev, the City of David is an integral part of the city of Jerusalem. People still live there. How could we find open land to excavate? How could we excavate in such a confined and often steeply sloped area? How would we assemble an expedition staff?

Pre-excavation planning took a full year, before the first spade struck the ground in the summer of 1978. 040We identified on a map possible areas for excavation—incorporating the suggestions of many people. We knew that not all of the areas could be excavated, mainly because most of the land in the City of David is privately owned. Just finding out what was and wasn’t privately owned turned out to be a project in itself. We undertook inquiries at a host of government agencies and had to examine the land registries not only from the Israeli period but also from the Jordanian, the British Mandate, and the Turkish periods as well.

The effort was worthwhile. We found that about four acres on the eastern slope at the southern extremity of the City of David had been purchased by Baron Edmond de Rothschild at the beginning of the century for the express purpose of conducting archaeological excavations in the City of David. This land was excavated in 1913–14 and 1923–24 by a French expedition under the leadership of Captain Raymond Weill. Known to this day to the local residents as “Rothschild’s land,” it belongs today to the state of Israel. When Baron de Rothschild bought this land for archaeological investigation at the beginning of the century, he could hardly have realized that he would be making a substantial contribution to the archaeological investigation of the City of David in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

A second plot in the City of David had been purchased by the government during the British Mandate. This gave us access to an area near the crest of the hill on the eastern slope, above the Gihon Spring. This area had been excavated by Macalister, Duncan, and again by Kenyon, but some space remained. The new excavations focus on these two areas; after the dig the areas will be preserved and restored as an archaeological garden.

To plan the excavation it was essential to consider physical conditions in the field: steepness of the slope, patterns of erosion, and location of previous excavations and their “dumps.” We also had to consider, as always, budget limitations. Finally, we had to consider everything learned by previous investigators in the City of David and by those excavating other areas of Jerusalem, so that we would integrate our discoveries into the historical mosaic of Jerusalem.

Months before the excavation season, we assembled the expedition staff. We wanted—and found—young archaeologists with no prior commitments. We wanted to be able to “harness” all their energies. The staff we put together is wide-ranging, young, serious at work, but light-spirited afterward. Giora Solar serves as architect, Rivkah Gonen as finds’ registrar, and Sari Gillon as administrator. A. de Grot, D. Terler, Karen Seger, D. Cohen and S. Lender were our field supervisors, and were assisted by many archaeology students. We also have a technical staff including photographer H. Shafir, pottery restorers, artists and surveyors. The field staff of 25 supervises approximately 90 expedition participants, mainly volunteers from around the world who came to uncover the City of David.

We began the excavation on July 2, 1978, near the crest of the eastern hill, above the Gihon Spring, in an area we called Area G.1 It was adjacent to the so-called “First Wall,” a fortification line excavated by Macalister and Duncan (1923–25), and reinvestigated by Kenyon in the 1960’s. Contrary to earlier suggestions, Kenyon demonstrated quite definitively that this wall dates to the period of the Second Temple (516 B.C.–70 A.D.). Under it, Kenyon found that ruins of the Israelite city destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.; we hoped to uncover the residential quarter of that same Israelite city. To our surprise, however, in the remaining unexcavated area (north of Kenyon’s large-trench), we encountered everywhere, the remains of a glacis which was between 15 and 20 feet thick! This glacis, or terre pisee (beaten earth) was composed of lenses or layers of alternating pebbles and earth, and was covered with a hard-packed soil layer and a facing of large stones. It had been partially excavated by Macalister when he dug next to the wall line, but he had failed to notice it. The glacis thickened and covered the face of a stepped stone glacis which had strengthened the city’s fortifications in the Second Temple period. This new and impressive defensive glacis helped to protect Jerusalem during the end of the second century and the first century B.C., the Hasmonean period.

The glacis not only covered the base of the city’s defensive fortifications, but also sealed beneath itself the remains of earlier periods when the city extended further down the slope. Thus the glacis had protected the remains from erosion which has badly disturbed similar remains elsewhere along the eastern slope of the City of David. During our second season this summer, we hope to remove the glacis; beneath it we 045expect to find building remains from the end of the Iron Age.

We found an occupation layer between the glacis base and the top of the Israelite buildings. This occupation layer, although visually unimpressive, contained Persian period pottery (6th–4th centuries B.C.). Similar pottery has been found in other Jerusalem excavations, but not within a stratified context. This is the first time that evidence for the period of the Return of the Exiles from Babylonia to Jerusalem has been excavated stratigraphically.

We continued our investigation of the fortification wall of the Second Temple period in another excavation area at the crest of the eastern slope, further south, along the old Weill excavation area (Area D). Before we could do this, however, we had to reexcavate and clean the remains that Weill had uncovered but which had over the decades been buried under earth and rubbish. In doing so we uncovered a stretch of wall about 55 feet long and over 10 feet wide. Beneath it we found the remains of earlier stone quarrying, predating the construction of this wall during the Second Temple period.

On the bare rock east of the wall—lower down the slope—we found a number of walls from the end of the Iron Age, and a pit full of whole and broken vessels from the 8th century B.C. This is one of the earliest assemblages of pottery from Israelite Jerusalem. Incised on a number of sherds were letters in the paleo-Hebrew script used at the time.

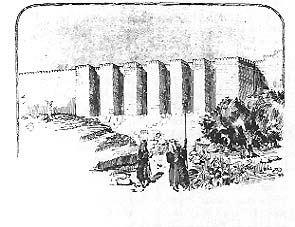

The two valleys which border the Biblical city on the east and west join together just below the southern tip of the City of David. The Central Valley (or Tyropoean Valley) separating the City of David from Mt. Zion on the west meets the eastern Kidron Valley. The southern end of the city was one of its more important and vulnerable areas. In 1897, Bliss and Dickie discovered a thick “buttress wall” that defended the entrance to the Central Valley from the Kidron Valley (see drawing). This buttress wall also served as a dam, creating a rich agricultural area behind it to the northwest. This wall is still preserved below the surface to a height of over 35 feet!

Today, the Jerusalem Municipality is planning to build a new drainage system just south of the City of David to collect rainwater flowing south out of the Old City. The modern drainage system, like the ancient ones, will be built under and around the City of David. Since the city will be digging up the road to install the new drainage system, we seized the opportunity to remove a stretch of asphalt road just east of the rock scarp that forms the southern tip of the City of David (Area A).

Despite the difficulties of excavation in a very confined area, we were able to reach bedrock in a number of squares. Beneath the remains of a Middle Age Mameluke stone pavement we found a clutter of massive walls often more than 12 feet thick. When we were able to sort out what we had found, it turned out we had struck an extension of the “buttress wall” at the Central Valley entrance, which extended northward into the Kidron Valley. We also found an ancient tower at the northern end of the wall which was part of this fortification system for the southern end of the City of David. Contrary to the relatively late date which Bliss and Dickie previously proposed for this wall system, we were able to securely date it to the Second Temple period. During that time (c. 515 B.C.–70 A.D.), and especially during the 1st century A.D. until the First Jewish Revolt (66 A.D.), this area served as a rubbish dump. We found thousands of jars, cooking pots, and stone and glass vessels which had been thrown outside the wall. We have been able to restore some of them.

The most unusual discovery from this area was a piece of a bone flute containing six holes for different notes. It was found in the wall collapse from the end of the Second Temple period—at the time of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. This rare flute is one of the few musical instruments ever discovered in ancient Israel by a stratigraphically-controlled excavation. Dr. Joseph Heller, a zoologist at Hebrew University, has 047determined that the flute was made from the foreleg of a cow. It is, of course, of great interest to musicologists and is being studied for publication by Dr. Bathja Bayer, also of Hebrew University.

Beneath the wall system from the second Temple period, we reexcavated an impressive corner which Bliss and Dickie had originally excavated. The corner, built of large, roughly dressed ashlar blocks, was probably once part of a tower. Its stratigraphic position, beneath walls of the Second Temple period, the kind of stones which were used, and the nature of the construction, suggest that the corner is a remnant from the Iron Age. Next to this corner, but beneath the foundation level of the later wall, we found a flimsy, stone wall fragment and a large cup mark in the rock. The pottery sherds associated with it enabled us to date it to the Iron II period.

At the foot of the eastern slope, mid-way between the southern tip and the Gihon Spring, we reexcavated to bedrock an area initially dug by Weill in 1913–14 (Area B). After Weill had partially excavated the area, he used it as a dump so that it was buried under a small mound of its own. It took tremendous effort in money and manpower to remove the dump. We then re-cleaned the rock face, and this year we hope to excavate a long section at this point from the crest of the hill down to the Kidron Valley.

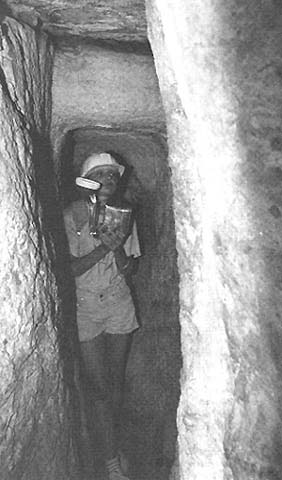

The Gihon Spring feeds one of the best known ancient water systems, Hezekiah’s Tunnel, under the City of David. The tunnel winds its way underground from the Gihon Spring to the Siloam Pool on the west side of the City of David; it was dug by King Hezekiah at the end of the eighth century B.C. Nearby is a much less well known earlier channel, which also carries the waters of the Gihon Spring, and which dates, perhaps, from the time of King Solomon (tenth century B.C.). This channel, known as the Siloam Tunnel, runs south along the eastern valley, sometimes underground, sometimes above ground. When in use, it emptied its waters into pools and fields at the southern end of the city.

The Siloam Tunnel differs from Hezekiah’s Tunnel in several respects; it is a much rougher and simpler construction and served only as a kind of aqueduct to carry the water from the spring. In cleaning the rock face under Weill’s dump, we uncovered three openings into the Siloam Tunnel. Along the course of the tunnel are openings, some of them natural fissures, others especially quarried out as windows facing the Kidron Valley. Water could be directed through 048these windows to agricultural plots along the Kidron, as well as into pools at the southern end of the city. Additional openings drained the runoff rainwater from the exposed rock of the eastern slope and carried it to the pools at the southern end of the city.

Although we were especially interested in exploring the Israelite and Canaanite occupation of the City of David, this is as difficult to do as it is interesting to search for. We would have liked to have dug on the crest of the hill, but the entire crest of the City of David is covered with houses. Moreover, in the areas excavated by Macalister and Crowfoot, and in many of the areas excavated by Kenyon, these archaeologists had found Roman and Byzantine remains resting directly on bedrock and obliterating all earlier Israelite and Canaanite remains. This same situation has been found in other areas of Jerusalem. Hoping to find some Iron Age strata, we decided to excavate an area below the Second Temple period wall line and above the wall line of the Iron Age city which Kenyon had discovered.

We focused our efforts on an unexplored terrace of the eastern slope which we were able to locate on an air photo survey and which we confirmed on a topographical survey. This terrace runs along the eastern slope, the result of an accumulation of earth and debris atop ancient walls and structures. We planned our excavations in this area (E) in a series of sections and squares covering 264 square yards and reaching a depth in some places of over 24 feet! This excavation was difficult both technically and archaeologically. After removing the debris which had accumulated from the end of the Second Temple period to the present day, we finally reached a thick layer of collapsed structures including a wall which was at least nine feet thick. We followed this wall for more than 75 feet of its length. It was constructed of large stones, and was built directly on bedrock. It had apparently functioned as a retaining wall for a terrace on which buildings were built. The wall probably also served as a fortification wall for the city itself.

After excavating the wall’s outer face, we opened a five by five meter square along its inner face, hoping to find structural remains related to the wall inside the city. Such remains would enable us to date the wall. After six weeks of intensive work, and the removal of 2000 years of debris, we uncovered three occupational phases from the eighth to the sixth centuries B.C.—remains from the end of Israelite Jerusalem. The latest phase was destroyed by the Babylonians in 049586 B.C. We believe that this thick wall served the city during most, if not all, of the Iron Age. The precise date of its construction is still unknown, but it is possible that it was originally built in the Bronze Age.

Just outside the wall, we found several natural pits in the rock which contained pottery sherds from the Early Bronze Age, at the end of the fourth millennium B.C., and even a few earlier pieces from the Chalcolithic Age. Thus, completely unexpectedly, we uncovered the remains of the earliest settlement in Jerusalem, dating to the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Undoubtedly, the earliest inhabitants settled on this ridge because it was close to the Gihon Spring.

An especially exciting surprise was the discovery of part of a monumental stone plaque bearing an eighth or seventh century B.C. Hebrew inscription. The inscription was found just outside the Iron Age wall. The fragment of red limestone measures about four inches square. Its face had been carefully smoothed, the three surviving lines had been painstakingly incised with a fine chisel, and the letters—all 15 of which are clearly readable—were carved in a beautiful, neat paleo-Hebrew script. Unfortunately, because only a fragment of the original inscription has been found, its interpretation is difficult. The inscription apparently makes mention of numbers: sb‘ “seven”; ‘sr “ten”; rb‘y “fourth.” For the present, any interpretation must be based on the first word, sbr (meaning to accumulate or to store). It seems to commemorate an important act of heaping or accumulating, perhaps for a royal building which bore the plaque.

This precious inscription is the outstanding find to date. But there were many other finds as well—from the Iron Age as well as from the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. These include pottery, glass vessels, weights, coins, and seal impressions. Outstanding among the seal impressions are those stamped on jar handles from the Iron Age II period. These stamped jar handles are known as L’Melech handles because they contain the letters lmlk, pronounced “l’melech” and meaning “belonging to the king.” We also found seal impressions from the Persian Period stamped yhd, which is to be read “Yehud,” the name of the sub-satrapy of Judea at the time of the Return of the Exiles. We found dozens of handles belonging to wine amphorae from Rhodes bearing seal impressions from this Greek island, evidence of fourth to second century B.C. wine imports to Judea.

The first excavation season has ended. The ancient hill of Jerusalem has provided answers exceeding all our expectations. The tremendous effort—by the expedition staff as well as by the volunteers (many of whom came originally for two weeks and ended up staying much longer)—has been well repaid. At present we are preparing the material for publication, and planning for this summer’s second season of work.

The City of David Society is also planning to preserve and restore the archaeological remains, both those which others have excavated in the past and those which we excavate during the current expedition. Eventually this area will be integrated into the archaeological garden surrounding the Old City. We have already cleared and cleaned part of the remains previously excavated in the City of David. In the near future we intend to create an overall plan for preservation and restoration.

If you would like to come and help us in our work, please contact the City of David Archaeological Expedition directly, at the Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel. We need and welcome your help.

Our first season of excavations in the City of David—the site of Biblical Jerusalem—ended with rich rewards and high expectations. The City of David, in geographical terms, is only a very small part of modern Jerusalem—a little spur which, to the surprise of many tourists, is located outside the walls of the Old City. To the archaeologist and historian, the City of David is the area occupied by Jerusalem in the Canaanite and Israelite periods, including the time of David (c. 1000 B.C.) 038Projecting from the eastern half of the southern wall of the Old City, the City […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username