Sir Flinders Petrie: Father of Palestinian Archaeology

044

Hundreds of years from now when a new generation of archaeologists uncovers a 20th century cemetery on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem, they may come upon the bones of a man buried without his head.

Surely this unusual burial custom, though rarely attested, will be worth a doctor’s dissertation. What strange religious rites could account for the bizarre inhumation? What could a budding young archaeologist learn about the society which practices such a custom? Is it understandable in light of the origin of the deceased? No doubt the expedition’s paleo-osteologist would identify the bones as those of a very old man—perhaps the state of the art will have so advanced that he could say with certainty that the man lived to be almost 90. Would that fact be somehow related to the headless burial?

It is likely that our putative doctoral student will be able from inscriptions to identify the bones as those of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the father of scientific archaeology in Palestine; but it is improbable that he will discover the true reason for the headless burial: Sir Flinders bequeathed his head to the Royal College of Surgeons in London for research purposes.

Petrie died in Jerusalem, however, not London. He was ten months short of his 90th birthday. The year was 1942 and there was a war going on. It was no easy task in the middle of a war to arrange for the shipment of a human head from Jerusalem to London.

At the time of Petrie’s death, his wife was living at the American School of Oriental Research in East Jerusalem. Rabbi Nelson Glueck, author of Rivers in the Desert and The Other Side of the Jordan, was then director of the school. It was he who was awakened at 4:00 a.m. by the nurse at Government Hospital on the day of Petrie’s death. Sir Flinders was breathing poorly, the nurse said; would he have Lady Petrie come to the hospital immediately. The great man died that night.

And it was Glueck who arranged to fulfill Petrie’s bequest of his head to the Royal College. Glueck once told me that he had to store the bequest for almost a year in a jar of formaldehyde in the basement of the school before he could get it transferred to London.

W. F. Albright, the acknowledged dean of Biblical archaeologists, spoke for the profession when he said that Petrie was, without doubt, the greatest archaeological genius of modern times, surpassing all others both in the number of sites he had excavated and the number of books he had published. Petrie had excavated at more than fifty sites and had written 98 books in whole or in part. More importantly, it was he who first put Near Eastern archaeology on a solid scientific foundation.

No one would have predicted Petrie’s success from a survey of his early life. Still-born on June 3, 1853, he was saved only by the quick work of an “experienced old nurse,” as he put it (Petrie 1932:4).a Shortly thereafter, 046another nurse dropped him on his head, and he suffered a blow that left a permanent mark in his skull at the temple. As a child, he was afflicted with chronic asthma so severe that he could not attend formal schools. Consequently, “The greatest archaeological genius of modern times” never went to school. Some may say that this is the best training for an archaeologist.

Petrie’s mother, Anne Flinders Petrie was a gifted linguist who had taught herself Hebrew, Greek, Latin, German, French, and Italian. She began “stuffing” Petrie with Latin and Greek grammar at the age of eight. His frail constitution broke under the pressure, however, and a doctor advised her to leave the boy alone for a couple of years. A new attempt at Latin and Greek grammar, when the boy was 10, also failed. Petrie later confessed that he had made no less than ten starts in Latin and five or six in Greek, but every one ended ignominiously; he forgot the early lessons as soon as he moved beyond them.

Petrie’s father was a strict Presbyterian who was always looking for the ideal tutor for young Flinders, that is, one who would instill the lad with the father’s own literalist religious beliefs. But the right tutor was never found.

As he grew up, young Flinders prowled the halls of the British Museum rather aimlessly and pursued an interest in coin collecting. He also explored and measured some churches and druid ruins in south England. Reportedly, he walked from site to site with his pockets filled with bread and cheese (his only food), and slept at whatever convenient farmstead would open its doors to him.

Apparently the bond between father and son was very strong in Flinders’ adolescent and early adult years; the father encouraged and helped the young man, who had no money or income, in his lonely wanderings and projects. William, the father, also helped his son acquire an old theodoliteb. Together they designed a surveyor’s 100-inch standard steel scale which would measure accurately site contours and building elevations. They remodeled the theodolite, adding efficient microscopes and other items until it was as accurate as the best new models available on the market. The only problem was that the makeshift instrument would yield accurate information only to the Petries.

In 1872, when Flinders was 19, father and son accurately surveyed Stonehenge with their improvised equipment. Hearing that the Society of Antiquaries was going to survey a series of monuments, young Petrie offered the Society his plan of Stonehenge. It was refused on the ground that his scale did not suit the series. Years later, however, Petrie’s plan of Stonehenge was adopted by the Society for its work at the site. Sir John Hope of the Society then remarked to Petrie, “I don’t see why you should not be one of us.” Petrie, still stung by the earlier refusal to accept his survey, replied, “I do not see why I should” (Petrie 1932:171.)

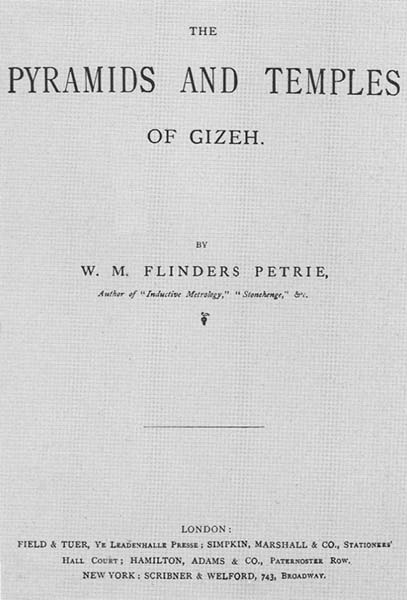

As a 13-year-old boy Flinders had read a book entitled Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid by Piazzi Smythe, a family friend. The book contended that the plans and measurements of the pyramids concealed prophecies of every event that was to befall the Children of Israel and the British Race. Smythe’s book captured the imagination of both young Flinders and his father. Many years later, in 1880 when Flinders was 27 years old, his father urged him to go to Egypt to measure the pyramids, hoping of course that Smythe’s theories would be confirmed. Thus Flinders Petrie was introduced to Egyptological research.

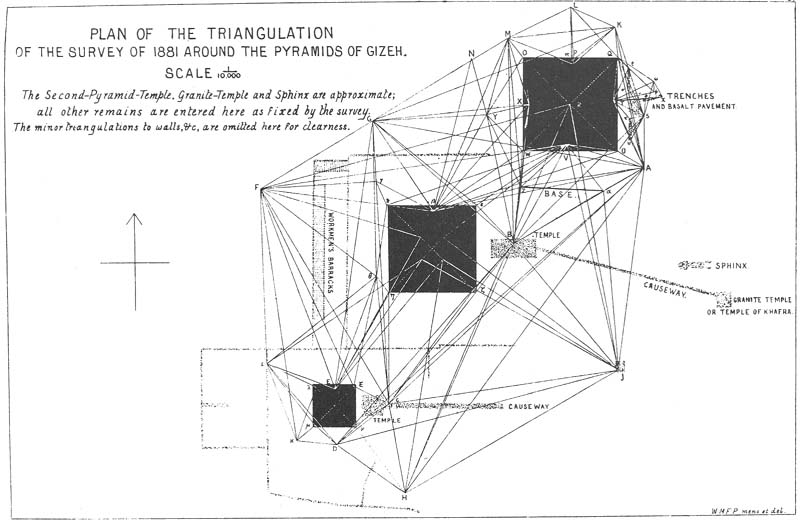

Several aspects of Petrie’s genius emerged in the course of measuring the great pyramid. First, he developed a strategy for accomplishing the task that would yield absolutely reliable results. A triangulation system was laid out to encompass the great pyramid and its two smaller neighbors, and a series of rock-drilled station marks was set up in a system in which observations from each station were interwoven and checked by the results of others.

Second, Petrie went about the task in a painstakingly slow and systematic manner, as though measuring the pyramids was the only task he would ever perform. After setting up his residence in a nearby empty tomb, Petrie organized his daily schedule around the stream of tourists who visited the site daily but were gone by 5:00 p.m. Accordingly, he worked inside the pyramid’s shafts and chambers from 5 o’clock to midnight. Because of the heat and dead air inside the pyramid chambers, Petrie stripped “entirely” during his night work (Petrie 1932:22). In the mornings and afternoons he wrote up his data and did outside survey work. Outside, he wore a “vest and pants” (British terms for undershirt and shorts) and was usually pink with dust and perspiration. This was enough to keep tourists at bay. As he put it, they thought he was “too queer for inspection” (Petrie 1932:22). Two years of work were required to complete the measurements.

Petrie also displayed his scientific bent of mind on this 049project by readily accepting all of the implications of the survey, even though they disproved Smythe’s theories. The base of the pyramid measured 9,069 inches instead of 9,140, which Smythe had postulated. This destroyed Smythe’s theory about the days of the year being represented in the measurement. In fact, none of Smythe’s prophetic theories could be supported by Petrie’s findings. This did not of course deter the theorists, who Petrie decided could “be left with the flat earth believers and other such people to whom a theory is dearer than a fact” (Petrie 1932:37). One theorist even tried to file down a granite boss (a raised area on a dressed stone) in the great pyramid’s antechamber to reduce its measurement to the size required by his theory (Petrie 1932:28).

On this his first project, as well as on subsequent ones, Petrie wrote up the results of his work as soon as it was completed. The pyramid survey manuscript was finished during the summer of 1883. Hearing that the Royal Society of Antiquaries had granted 100 pounds for the Royal Engineers to make such a survey, Petrie wrote that he had already done the work and that he had finished the report. Francis Galton of the Society was delegated to evaluate the survey, and in due time he pronounced it sound. Instead of sending out the Royal Engineers, the Society simply awarded Petrie the 100 pounds and published his report. It was the first grant he ever received.

Petrie, by then 30 years old, was greatly encouraged by the fact that the Royal Society had “discovered” him. Until then he had earned no income and was entirely dependent on his father’s support. Young Petrie was also pleased because his interest had shifted from checking out prophetic theories about the great pyramid to a deep concern for the antiquities of Egypt. In short, he wanted to dig. Needing the support of the professional organizations, he first approached the Egypt Exploration Fund, but the management of the Fund opposed taking on the young archaeologist because he had not attended a 050university. However, Erasmus Wilson, the Fund’s major patron, had seen Petrie’s pyramid book, and insisted that he be given an opportunity, albeit without stipend. As a result, Petrie began working under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Fund in October, 1883, gratis.

Leaving Cairo on November 6, 1883, Petrie made his way toward Tanis, the ancient Delta capital of the Pharaoh of the Exodus, with instructions to examine and draw plans of some late temple ruins in the area. On the way to Tanis he had the kind of beginner’s luck that every archaeologist fantasizes about at some point in his career.

The same insatiable curiosity that caused him as a lad to inspect every byway on his lonely bread and cheese wanderings among the druid ruins in England now compelled Petrie to examine with his intense eyes every ancient site between Cairo and Tanis. In particular he sought the place from which an archaic Greek vase, purchased in Cairo, had come. Tramping systematically over an area in the vicinity of Damanhur and nursing a feverish cold, Petrie came upon a low mound of town ruins and a sight “… almost too strange to believe” (Petrie: Ten Years: 36). Local villagers had dug out the core of the mound to obtain its fertile earth. Their wide, shallow crater bared the lowest level of an ancient town.

Walking into the crater, Petrie felt something crunch under his boots. Looking down he was amazed to see “ … the whole ground thick with early Greek pottery” (Petrie 1932:40). Pieces with fret and honeysuckle patterns, painted figures of animals and gods, and even statuettes, lay all around him in such profusion that he felt he was “ … wandering in the smashings of the Museum vase rooms” (Petrie 1932:40). Petrie had stumbled upon the ancient town of Naukratis, the first known Greek colony in Egypt dating before the time of Alexander the Great who died in 323 B.C.

Flushed with the excitement of easy but dramatic finds at Naukratis, Petrie continued work in the Delta until 1886, excavating in the vicinity of Tanis under the auspices of the Egypt Exploration Fund. During this time 051he began a long series of annual exhibitions in London, each summer displaying objects collected from his excavations of the previous winter in Egypt. The exhibitions attracted public interest in Petrie’s work, to the extent that he “bid goodbye” to the Fund in the fall of 1886 because its “constant mismanagement of affairs in London made the conditions of work … impossible” (Petrie 1932:78). His exhibitions grew from their beginnings in a shed at the back of an antiquities dealer’s garden to a permanent arrangement at University College, where Petrie would be named to a professorship in 1892. Within four years he had an established reputation as an archaeologist and collector.

In the fall of 1886, Petrie set out to explore ancient remains up the Nile River from Cairo. With a small grant from the Royal Society he did a series of “Racial Portraits,” detailed studies and photographs of heads depicted on monuments. This expedition, as one would expect, opened many opportunities; Petrie was able to work at sites between Cairo and Elephantine, and in the Fayum west of the Nile, until the spring of 1890.

During these years Petrie had only 110 pounds of fixed income per year, coming from a great-aunt and a small share in family property in England. About 40 pounds went for living expenses in England during the summers, and 70 pounds was left for work in Egypt the rest of the year. In fact, Petrie had no other fixed income than this pittance until he was near forty years old, when he became a professor at University College in London.

From the outset, the management of the Fund questioned Petrie’s motives. Why would Petrie go to Egypt with little or no support? In a long letter written in late 1893 to his friend Flaxman Spurrell, a young doctor interested in archaeology, Petrie explained:

“You seem to take for granted that as I am not working for money … I must therefore be working for fame,” he said. “But would you be surprised to hear that this is not my mainspring? … I work because I can do what I am doing, better than I can do anything else … And I am aware that such work is what I am best fitted for. If credit of any sort comes from such work, I have no objection of any sort to it; but it is not what stirs me to work at all. I believe that I should do just the same in quantity and quality if all that I did was published in someone else’s name” (Petrie 1932:42).

Another motive gripped him shortly after he began excavating in Egypt and changed the easy-going pace of his work. He was shocked at the pillage he saw masquerading as excavation (Wilson 1964:94). Early excavators in Egypt found such a wealth of museum-quality objects that they carelessly threw aside uninscribed weights, tools, weapons, and undecorated or broken pottery. Many excavators worked in absentia, depending on local foremen to supervise the operation. Petrie felt that Egypt’s past was “on fire,” and he seemed to be the only one concerned about saving it.

While friends in London questioned Petrie’s motives for working without a stipend, others distanced themselves from him because of his Spartan life in the field. “He ignored physical comforts for himself, and, therefore, neglected to provide the ordinary amenities for his staff,” reported John A. Wilson, the noted Egyptian historian (Wilson 1964:93). At one site his table for working and eating was in a dim room lit by apertures in the wall near the ceiling. A double row of tin cans containing various kinds of food stood in a trough down the center of the table. When the hunger pangs became intense, Petrie would open several cans and eat from them at random as he talked or worked. Two volunteers who later became a well-known husband and wife excavation team, Annie and Edward Quibell, became engaged while nursing each other through a bout of ptomaine poisoning contracted on a Petrie dig (Wilson 1964:93).

Extreme frugality also was evident in the inexpensive equipment and gadgets with which Petrie did his work. The ancient theodolite used at Stonehenge apparently continued its service in Egypt. Nevertheless, Petrie’s work was precise enough that he could praise the skill of those 052ancient Egyptians who laid out the base of the great pyramid. “Its errors,” he said “both in length and in angles, could be covered by placing one’s thumb on them … ” (Petrie 1892:19). His camera also became legendary. H. E. Winlock, Egyptologist for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reported that Petrie “took an old camera, put a bit of rubber hose in the frontboard with a good sized lens in it, and had a wire fixed so that he could hold the lens wherever he wanted it … crooked or not in regard to the plate.” He took superb pictures with it, however. (Wilson 1964:97).

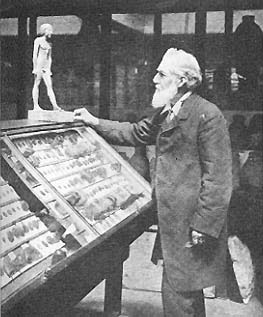

Despite the penurious amenities of his camps, Petrie had the bearing and appearance of genius. His eyes burned. Charles E. Wilbour, an “active tripper” (Petrie’s term for tour leader) visited the excavation camp at Meidum, and reported that the ladies on his boat had commented that Petrie had “eagle’s eyes.” A tourist in Cairo said he had “the eyes of an animal” (Wilson 1964:93). Wilson said he looked like Michelangelo’s Moses, with his patriarchal beard, high brow, and his searching eyes (Wilson 1964:93). Something about his face and eyes seemed incompatible with the dusty sockless feet slipped into down-at-the-heel shoes.

Petrie continued work in Egypt until 1926, except for an interlude in the spring of 1890 to excavate at Tell el-Hesi. Any one of the major sites explored by him could adorn the career of an archaeologist today: Tell el-Amarna, with its sprawling palaces of Akhenaton and priceless artwork in sculpture, reliefs, and frescoes; Abydos, with its rich tombs of the first two Egyptian dynasties; Sinai, and its earliest known alphabetic inscriptions in proto-Canaanite; and numerous pyramids, mastabas, and temples between Cairo and Luxor.

One discovery of special interest was the Merneptah Stele, naming Israel, found in the mortuary temple of Merneptah at Thebes in the spring of 1896. The black granite slab standing more than ten feet high was revealed by a trench running up to the corner of a room in the temple. Impatient to wait for complete clearing of the room and the laborious removal of the heavy stone, Professor Wilhelm Spiegelberg, an Egyptologist, was called in to copy the inscription. Lying on his back in the cramped space at the base of the stele, the professor copied the final few lines and came out saying to Petrie:

“There are names of various Syrian towns, and one which I do not know, Isirar.”

“Why, that is Israel,” Petrie replied.

“So it is,” remarked Spiegelberg, “and won’t the reverends be pleased!”

Petrie remarked at dinner that night: “This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found” (Petrie 1932:172).

But Petrie is best known to Palestine archaeologists for having first perceived two fundamental principles of archaeological research which had escaped everyone prior to him. First, he discovered that bread and butter information for the archaeologist was to be found in the “unconsidered trifles,” as he characterized them: the unspectacular but plentiful artifacts that everyone else at the time discarded on the dump. Pottery fragments especially were recognized as “ … the very key to digging … the alphabet of work” (Petrie, Ten Years: 158)

This insight was firmly established by 1890, seven years after Petrie completed his pyramid surveys. Still disillusioned by bickering among the members of the Egypt Exploration Fund, yet at the same time needing professional support for his research, Petrie “pledged” to go to work for the Palestine Exploration Fund. His orders were to examine Umm Lakis and Khirbet Ajlan in the coastal plain area, because the names of these sites reflected the Biblical names of Lachish and Eglon.

Three days work at Umm Lakis convinced Petrie of its late Roman date, so he set out to explore other sites in the region. Coming upon the imposing mound of Tell el-Hesi, Petrie noted that the Wadi Hesi, flowing close against the steep east side of the ancient ruin, had actually undercut it. Over the centuries a large section of the mound had fallen into the wadi and washed away, leaving a cross-section of stratification from top to bottom visible to Petrie’s perceptive eye.

In the year 1890, that the nature of a tell consisted of a sequence of occupational layers was not generally understood. The German “dilettante banker” turned archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, had first recognized in the 1870’s at Troy that a site may contain the accumulation of successive cities (Albright 1964:114). But nobody had actually drawn a vertical section of natural stratification until Petrie went to Hesi in 1890.

Working at the exposed side of the tell, Petrie recovered enough pottery to show that an evolution in forms corresponded to the succession of strata. This was the second fundamental principle of archaeological research that was established almost casually at Hesi. It was to become a pivotal event in Palestinian archaeology and in the development of the young discipline.

After four months of exploration, six weeks of which were spent digging at Hesi, Petrie decided to return to Egypt because he found the working conditions in Palestine intolerable. On one occasion, he had been robbed and choked by four assailants. The Palestinian laborers were, he said, unreliable, even though a man and a girl could be hired for one shilling per day. And the water was 054the worst. The brackish and stagnant water at Hesi, he said, was, when boiled, three courses in one: soup, fish, and greens. He also felt pressure from England to complete the writing of his Egyptian reports. On June 28, 1890 he was back in London not to return again to work in Palestine until 1926.

In Egypt, Petrie was overwhelmed with sites richer in finds than those in Palestine, but lacking the impressive layer-cake sequences of strata that were evident at Hesi. After digging at Hesi Petrie’s interest seems to have focused mainly upon pottery and collectible objects as keys to strata identification. However, the development of a controlled scientific method for excavating successive layers, like those visible in the mound at Hesi, remained for his successors in the British School of Archaeology to work out a generation later.

Petrie’s system for bringing order into the classification of relatively unstratified pottery was quite original. He called the system “sequence-dating,” and demonstrated it conclusively in the Diospolis Parva report (Albright 1964:115), at a site at Nag Hamadi in Upper Egypt.

What was “sequence-dating”? Suppose we have a huge collection of pottery, weapons, tools, jewelry, etc., from an Egyptian site, but we do not know what levels it came from, nor even which is earlier and which is later. How can some order be brought into the study of such a collection? Petrie’s analytical eye perceived that pottery and other artifacts tended to fall into families of form, ware, and decoration, and that one family of forms seemed gradually to evolve into another. He concluded from observations of strata that these successions of related assemblages had historical correspondences and that links, or synchronisms, could be found.

As a result, Petrie devised a system of “sequence dating,” arbitrarily assigning numbers to the families of related forms beginning with S.D. (sequence dating) 31. Why 31? He left the first 30 numbers open for future discovery, and worked out a scheme for S.D. 31 through S.D. 80, using materials in hand. The sequence dates were not, of course, dates. However, the hypothetical structure, or model, of sequentially related families was the first step toward funding a dated context into which they would fit. Petrie was the first, therefore, to analyze sufficiently the technical aspects of pottery and objects in order to prove a typological development which corresponded to historical phases. It was a breakthrough in critical analysis that laid the foundations for the modern archaeological sciences of typology and stratigraphy.

Because of continuing problems with the Egypt Exploration Fund management, Petrie had set up a publicly-subscribed Egypt Research Account to support his work and that of his students. In 1905 he and some friends organized the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, and subsumed the Research Account in the new organization.

The new arrangement seems to have served him well during the years of World War I, when he spent much of his time writing reports, and during the 1920’s when archaeology in Egypt came under increasingly autocratic control of the French Directors of Antiquities. By 1926, the British School Committee decided it was more desirable to transfer Petrie’s work to the “Egyptian sites in Palestine—Egypt over the Border” (Petrie 1932:275). Taking a half-dozen of his Qufti (Coptic) foremen with him, Petrie made his way to Gaza with his wife whom he had married in 1897, Lankester Harding, and the James L. Starkeys among others.

Under difficult circumstances, Petrie worked the next few years at Gaza, Jemmeh, Ajjul, Tell el-Far’ah (South), and other sites. He recruited Olga Tufnell and Dunscombe Colt, whose contributions to Palestinian archaeology are now well-known. His interest spread beyond excavations in many directions, from the continuing demands of exhibits in London to problems of securing museum space to house his discoveries; from writing up the ever-present reports to preparing general works such as Decorative Patterns of the Ancient World, a Corpus of Palestinian Pottery, Objects of Daily Life, and other spin-off projects that could have gone on forever.

055

Albright noted that during the decade after Petrie moved to Palestine, he continued as indefatigably as ever, but was no longer in the vanguard of progress (Albright 1942:8). The American school of Reisner and Fisher with its detailed excavating and recording techniques had moved beyond Petrie’s pioneering stage, and many of his conclusions about chronology and site identifications came under increasing reexamination. In the summer of 1935, beset by increasing age and bothered by rumblings of another World War, Sir Flinders and Lady Petrie, together with the library and office of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt, moved into the building of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem (now the Albright Institute), where they remained until Petrie’s death in 1942 (Albright 1942:8).

In retrospect, one wonders if Petrie did not reach the apogee of his career at Hesi in 1890. Until then his total absorption was with archaeology. He had reached the pioneering insights that made him the father of modern archaeology. After 1890 he became more and more involved in the accoutrements of success: exhibitions, the lecture circuit, promotional schemes, feuds with the opposition, organizational power struggles, which devolved at last into a feeling that the world had passed him by. In any case his concepts that were to shape archaeological research until World War II were exploited and developed by others, not Petrie. His contributions, however, will always remain a landmark in the progress of archaeology from treasure hunt to science.

Bibliography

W. F. Albright, “Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie, 1853–1942,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 87, October 1942, pp. 7–8.

N. Glueck, “Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie, 1853–1942,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 87, October 1942, pp. 6–7.

W. M. Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology, Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1932.

W. M. Flinders Petrie. Ten Years Digging in Egypt, Fleming H. Revell Co., Chicago, 1892.

J. A. Wilson, Signs and Wonders Upon Pharaoh, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1964.

H. E. Winlock, “Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942)” American Philosophical Society Yearbook, 1942, pp. 358–62.

Hundreds of years from now when a new generation of archaeologists uncovers a 20th century cemetery on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem, they may come upon the bones of a man buried without his head.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username