The Israelite Occupation of Canaan: An Account of the Archaeological Evidence

014

The archaeological time period known as the Iron Age—or the Israelite period, as I shall call it here—began in about 1,200 B.C. and lasted for about 600 years. In the Land of Israel, it ended with the destruction of the First Temple in 587 B.C. Scholars generally agree that the penetration and settlement by the Israelites into the various regions of the country began, at the latest, in the 13th century B.C. As I shall show, it quite probably began, in fact, in the 14th century. Thus the period of the “conquest” began in the Late Canaanite period, that is, in the Late Bronze Age (1,550 B.C.–1,200 B.C.), according to standard archaeological terminology.

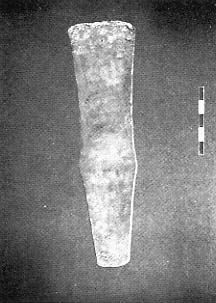

Although the so-called Iron Age began in about 1,200 B.C., iron came into widespread use in Canaan only in about 1,000 B.C. Although iron first appeared during the 14th–13th centuries, this was only in the Hittite kingdom, where it was protected as a monopoly. With the fall of the Hittite empire at the end of the 13th century, the use of iron gradually spread. Nevertheless, during the Israelite I period (or Iron I, as it is commonly called, 1,200–B.C. 1,000 B.C.), bronze was still the common metal; the use of iron was quite rare. At Megiddo all the metal implements in the Israelite I strata were made of bronze, except for one iron knife. This was also true in the Megiddo tombs; iron objects were extremely rare—only two rings and two knife blades were found associated with pottery from the 12th–11th centuries, in contrast to the abundance of bronze implements. At the Israelite settlement of Tel Masos, which existed from the end of the 13th century to approximately the end of the 10th century, all the metal implements were made of bronze, except for a sickle and a knife blade. At Beersheba there were two iron sickles in Stratum VI from the early 10th century B.C. An iron plow blade was found at Gibeah of Saul (Tell el Ful) in the fortress from the reign of Saul (late 11th century B.C.). Thus, it is clear that the appearance of iron in Israelite I was rare and sporadic and that iron had no significance in the technology of that time. Its widespread use in the Land of Israel began only with the Israelite monarchy (1,000 B.C.) when it became the dominant metal in tools and weapons.

It is generally assumed that the Philistines brought the knowledge of ironworking to the Land of Israel and that they kept it as a monopoly until King David broke their power. This assumption is based on 1 Samuel 13:19–20:

“There was no smith to be found throughout all the land of Israel; for the Philistines said, ‘Lest the Hebrews make themselves swords or spears’; but every one of the Israelites went down to the Philistines to sharpen his plowshare, his mattock, his axe, or his sickle.”

Note, however, that the verse does not specifically mention ironworking. Since the tools found in the Israelite sites of this period were made of bronze, metalworking in general was probably referred to in this passage.

It is true that the widespread use of iron occurred at the time when Philistine hegemony was broken. At first glance this appears to give support to the assumption that iron making had previously been a Philistine monopoly. But thus far no substantial archaeological evidence indicates that iron had been widely used in Philistia before it was widely used at Israelite sites. In the only Philistine capital that was extensively excavated—Ashdod—iron implements were not found in the early Philistine strata. At Tel Qasile, a city founded by the Philistines on the bank of the Yarkon River, there is no iron from the two earliest strata (XII–XI). Indeed, iron first appeared only at the end of the 11th century (Stratum X). True, in the Philistine temple from Stratum XII, an iron blade with an ivory handle was found, but precisely because this is such an exceptional find, we must conclude that at this time iron was regarded as a precious and rare metal even by the Philistines. Even in the Philistine temple of Stratum X at Tel Qasile, an iron bracelet was uncovered, indicating iron was still being used for jewelry. This was also the case at Israelite sites in Israelite I, when the new metal was considered both rare and costly and served mainly for jewelry.

015

Thus it is doubtful that the Philistines had a monopoly on iron production. It became more widely distributed at the end of the 11th century because commercial ties with the north intensified at that time, especially by the sea routes, as attested by the appearance of a new imported product, Cypro-Phoenician ware.

About the year 1,200 B.C., Mycenean sea power came to an end. This is also the approximate date of the destruction of Troy. It is the date of the collapse of the Hittite empire and of the destruction of the great city-states in northern Syria such as Alalakh and Ugarit. Major ethnic movements for which there are few precedents in human history followed on the heels of this upheaval. The penetration of the Israelite tribes and related Hebrew groups into Canaan is a marginal feature of this movement which changed the entire ethnic and political order of the eastern Mediterranean and the lands of the Fertile Crescent. Other ethnic movements included the entry of the Dorians into Greece, the movement of the Sea Peoples across the expanses of the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Phrygian thrust into central Anatolia, and the Aramean migration into Mesopotamia and Syria. These ethnic waves brought an end to the city-states that had characterized Canaan and Syria (except for the cities of Phoenicia that preserved a spark of Canaanite culture).

The new tribal league of Israelites that appeared on the stage of history reflected a national tie far broader than that of the city-states that preceded the Israelite entry into Canaan. With this entry began an era of national states that henceforth stamped their imprint on the Land of Israel and the territories surrounding it.

The year 1,200 B.C. does not, therefore, correspond with the introduction of iron, which came later, nor with the destruction of the Canaanite cities, which was partly earlier and partly later, nor was the beginning of Israelite settlement, which was also earlier. Nevertheless, the year 1,200 remains the most appropriate date for designating the beginning of a new period, one of the decisive turning points in the history of the country.

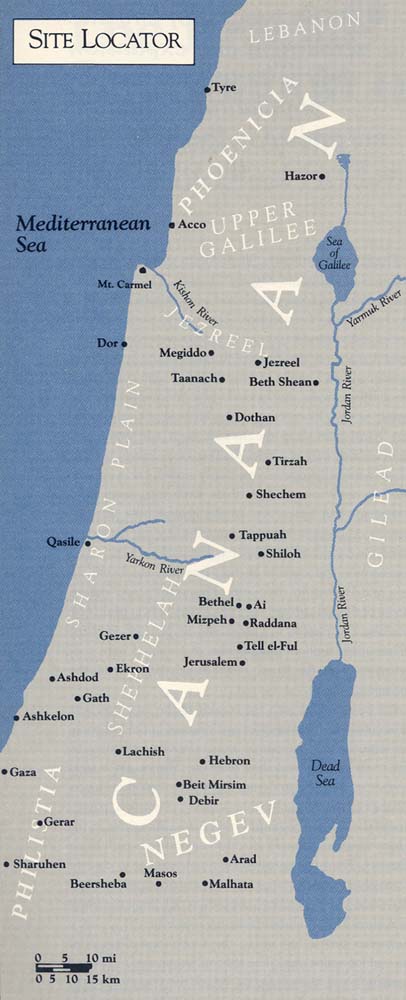

The Israelite settlement differed from every previous occupation wave in the country’s history. Throughout the entire Canaanite period there had been striking differences in the density of settlement. The valleys were intensely settled. Strong and important kingdoms were found on the coastal plain, in the Shephelah, and in the Jezreel and Jordan valleys. The flat and fertile plains were convenient for cultivation. In the foothills (the Shephelah) copious springs flowed. By contrast, in the hilly regions only northern Transjordan (from the Yarmuk basin northward) and the northern part of Upper Galilee were densely settled. Most of the hilly regions were thinly settled. Large areas in the hills were forested with thick scrub that discouraged settlement and agriculture. In the central hills, the Canaanite occupation was concentrated along the backbone, down the watershed road that ran from Debir, Hebron, and Jerusalem in the south to Bethel, Tappuah, Shechem, Tirzah, and Dothan in the north. The western and eastern slopes of the hill country were practically unoccupied. This was also the picture in Gilead and in parts of southern Transjordan; the few communities that existed were concentrated along the length of the King’s Highway on the mountain plateau.

All this changed with the coming of the Israelites. The unoccupied and very sparsely settled areas in the hill country were the very regions of most intensive settlement by the tribes of Israel and their relatives. The reason is clear both from the Bible and from the archaeological evidence. At the beginning, the Israelites lacked the strength to overpower the strong Canaanite cities, particularly those in the plains which could make effective use of their superb battle chariots. The Israelite tribes had no choice but to content themselves in the first stage of their settlement with peripheral areas where they faced opposition only from the forces of nature. Thus, Joshua advised his own tribe: “If you are a numerous people, go up to the forest, and there clear ground for yourselves.” The tribe of Joseph said, “The hill country is not enough for us, yet all the Canaanites who dwell in the plain have chariots of iron.” Then Joshua said 016to the house of Joseph, “You are a numerous people, and have great power: … the hill country shall be yours, for though it is a forest, you shall clear it and possess it to its farthest borders … ” Joshua 17:14–18).

Many of these initial Israelite settlements are known from archaeological surveys, but only a few have been excavated. No doubt more detailed answers concerning the dates of the Israelite settlement and its character can be obtained from intensified research on these communities, rather than from the large tells were most excavation has been concentrated until now.

For example, an illuminating picture of early Israelite communities was revealed in a survey in southern Upper Galilee. This territory was not occupied at all prior to Israelite I, except for a few sites from Middle Canaanite I (c. 1,800 B.C.) that appeared here and there. A dense network of Israelite settlements was discovered in this area, founded over a short period of time at small distances from one another. Density of settlement was never again as high. Pottery from Early Israelite I (1,200 B.C.–1,000 B.C.) even exceeds pottery from Israelite II (1,000–587 B.C.).

A similar situation was found in the hill country of Ephraim and Judah. In particular along the slopes somewhat farther removed from the spine of the hill country, surveyors discovered many small settlements that had their beginnings in the period of initial Israelite penetration. Many were never occupied again, even in Israelite II. Excavations have been carried out at a few of these places, for example, at Shiloh, Ai, Khirbet Raddana, Mispah (Tell en-Nasbeh) and Gibeah of Benjamin (Tell el-Ful). In all of these, occupation was actually established with the Israelite settlement. There is a gap of hundreds of years between the Israelite settlement and the next earlier occupations. Most of these communities were destroyed before the end of Israelite I, in the middle of the 11th century at the latest. Some of them were never reoccupied (Ai, Raddana) and others only after a gap (Gibeah of Benjamin at the end of the 11th century and Shiloh only in Israelite II). Again, extensive settlement was prominent only precisely in the period of initial Israelite penetration.

From Ai and Raddana we get some idea of the architecture in these communities. The houses generally include a courtyard and two or three rooms. This is the so-called four-room house (three rooms plus a pillared courtyard). Squared orthostat pillars for supporting the roof beams are a characteristic feature. The use of stone pillars—monoliths and flat slabs—is henceforth characteristic of Israelite houses until the destruction of the first temple in 587 B.C. Pillars are rare in Canaanite settlements and are almost never found in common houses. The wide diffusion of pillars in Israelite settlements at such an early period supports the theory that this was an architectural practice 017brought by the tribes when they came into the land. The source of this architectural feature is still unknown. This common technical knowledge of architecture, however, is evidence that the tribes were not completely nomadic when they arrived in the country.

At both Ai and Radanna plastered water cisterns hewn out of the rock were found in the courtyards of these houses. These cisterns collected rainwater from the roofs of the houses and from the courtyards. This served as the main water source throughout most of the year. Water cisterns are also found occasionally in Canaanite settlements, but in Israelite settlements, by contrast, they are widespread. Cisterns were essential in unwalled communities in the hill regions because these communities were far from springs or other sources of living water and distant sources of living water could easily be denied to them by an enemy laying siege. By these cisterns and otherwise, the tribes swiftly adapted themselves to the technological means necessary to settlement in the hilly areas available to them.

The settlement picture in the Biblical Negev is especially illuminating, that is, in the transition zone between the settled area and the southern wastes, north and southeast of Beersheba. This area was not occupied at all in the Late Canaanite period (1,550–1,200 B.C.).

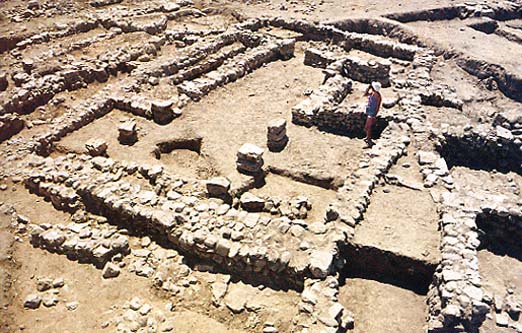

In this arid area Israelite settlements were established in Israelite I at every possible site. As usual, only the main tells have been excavated, and all of them were occupied during this period: Beersheba for the first time in its history and the other three—Arad, Tel Malhata, and Tel Masos—after a long period of abandonment. Tel Masos is especially important for understanding the Israelite occupation of Canaan. Tel Masos was destroyed at the end of Israelite I (about 1,000 B.C.) at which time it had been an unfortified village for about 200 years and was spread over an area of about 10 acres. It had three strata. The latest stratum, which came to an end, as mentioned above, at the end of Israelite I, made use in large measure of earlier structures. The second stratum is the best preserved, and modifications in the house plans testify to its long duration. The oldest stratum was exposed only in small measure, but even there pillared houses were found with pillars made of flat stones. This stratum was preceded by seminomadic settlement from which only cisterns and granaries have been preserved. Remains of the three Israelite strata were found in every one of the widely distributed excavation areas, evidence that even in the earliest phase the village had reached its greatest proportions.

In the second Israelite stratum, the best preserved, house after house was discovered, most of them pillared houses of the typical “four-room” plan. The entry was to a central courtyard with rooms on three sides, usually with two rows of columns delineating the two side units from the courtyard. This type of house did not change during the entire Israelite period, except for the addition of a second story. At Tel Masos, no staircases were found, such as were commonly used in the “four-room” houses of the monarchical period (Israelite II).

Obviously this house plan did not originate at Tel Masos. We do not know where this plan developed. However, it is clearly a well defined architectural feature which may be considered a trademark of Israelite occupation. At Tel Masos a few public buildings were also found which served as a sort of stockade in times of need. Their size and excellent construction testify to the highly developed public organization of the settlement.

The Israelite settlement at Tel Masos makes it necessary to modify our view of the Israelite occupation of Canaan to a great extent. This was not a military conquest, but rather, as in the internal areas of the country and other peripheral zones, we see a clear picture of penetration into a previously unoccupied region. The Israelite tribes were not deterred by the special difficulties of settling in the arid Negev, which they accomplished only by using their appreciable technological skills and by carefully utilizing water sources. More than anything else, this movement testifies to the great hunger for land on the part of tribes compelled to settle down.

At the same time the picture of political conditions is quite different from the Biblical characterization of the period: “There was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes.” (Judges 17:6) If a large, well-established settlement like Tel Masos could exist for more than two centuries without the need for any real fortifications, the implication is that no serious force threatened its peaceful way of life. After the decline of Canaan and Egyptian authority during the 13th century, no political force was capable of competing with the Israelite tribes. Thus, they settled down in these areas until the Philistine military power rose ominously in the mid–11th century.

The picture of the settlement we get from Tel Masos is consistent with a narrative about one of the settlements of Simeon preserved in Chronicles, although Chronicles concerns Gedor (Gerar, according to the Septuagint), rather than Tel Masos: “They journeyed to the entrance of Gedor to the east side of the valley, to seek pasture for their flocks, where they found rich, good pasture, and the land was very broad, quiet, and peaceful; for the former inhabitants there belonged to Ham.” (1 Chronicles 4:39–40) “The sons of Ham” is a general concept covering Egyptians, Canaanites, 018and Philistines together. It would appear that the reminiscence of the earlier communities from Middle Canaanite II in the area was already blurred.

The picture at Beersheba is similar to that at Tel Masos, but since the earlier remains are hidden under the fortifications of the city from the monarchical period, the information is meager and fragmented. Three strata from Israelite I (VIII–VI) were also found, preceded by a phase during which cisterns and silos had been carved out of the bedrock. Yet even here there were pillared houses, and in the latest stratum (VI) a staircase was found, proving the existence of an upper story. A well associated with the earlier strata was found hewn in the bedrock to a depth of more than 40 meters. This is a remarkable technical achievement. All the other wells in the area are in the vicinity of the wadi, where the upper water table is no more than 10 meters deep.

The Israelite settlement in the northern Negev began at the end of the 13th century; by the end of the 11th century it reached the southernmost corners of the Negev. Israelite settlements in the northern hill regions, on the other hand, began earlier, in the 14th century B.C. The data are still sparse, but archaeological discoveries support the historical sources, which point in this direction.

In the Bible there are various hints of two main waves of penetration into Canaan. The later wave, associated with the Exodus, came in the mid–13th century B.C., as indicated by the construction of the city referred to in the Bible as Ramses, the city of Pharaoh Ramses II. The date of this wave is also indicated by the fact that Israel is mentioned as a consolidated community in Canaan in the famous Merneptah Stele dated to 1,220 B.C. We may therefore assume that the earlier wave of Israelite penetration into Canaan occurred during the second half of the 14th century and that various tribes had probably come into Canaan even earlier.

It is still quite difficult to fix the date for the founding of the various Israelite settlements. The widely accepted date, the beginning of the 12th century, has no archaeological basis. It should be noted that pottery has been found from Late Canaanite II at no fewer than three of the Israelite settlements: Shiloh, Mizpah, and Gibeah of Saul.

The Israelite communities in various parts of the country manifest with great clarity the general character of the Israelite penetration and settlement. This penetration and settlement occurred mainly in unoccupied or sparsely settled areas, a picture that corresponds to the description in the book of Judges, contrasting to the picture of unified conquest reflected in the book of Joshua. At the same time a great uniformity is discernible in the material culture of 019these communities in the different regions, testifying to a strong tie among the tribes.

No doubt certain Canaanite settlements fell into the hands of the tribes and were conquered as opportunity presented itself. It is possible that the fort of Jericho and, perhaps, Bethel were conquered with the arrival of the early wave of tribes in the second half of the 14th century. However, in general, there is no way of establishing whether a particular Canaanite city was taken at the beginning of the Israelite penetration or whether it fell to the tribes at some later stage. For the most part, the second alternative would seem to be correct. The various tells in the Shephelah were taken toward the end of the 13th or beginning of the 12th century, and even the invasion by the later Israelite wave apparently took place in approximately the mid–13th century. Obviously, the Negev settlements were founded by this second wave of Israelites at the beginning of the second half of the 13th century.

The Israelite settlement of the hilly regions began, as previously mentioned, about 100 or more years earlier. The only northern site whose destruction by Israel can be dated is Hazor. There is no reason to assume that Hazor was conquered by new tribes that came from the desert. On the contrary, in the temporary Israelite settlement established on the ruins of the Canaanite city of Hazor, the ceramics were typical of the usual Israelite settlements in the Galilee. If these new occupants did take part in the conquest of Hazor, we must assume that they came from the Galilean mountains.

The diffusion of the tribes into the more densely populated Canaanite areas and the subjugation of most of the Canaanite cities thus belonged to the second phase of the period of the judges, and this happened at various times. Most of the cities of the Shephelah and Hazor had already fallen by about the end of the 13th century. Shechem succumbed only in the mid–12th century as a result of the quarrel with Abimelech, son of Gideon (Judges 9). In the first chapter of Judges there is a detailed list of Canaanite towns that withstood the pressure of the various tribes. Some towns held out during the entire period of the judges and only fell at the hands of King David; these included Jerusalem and Gezer and, apparently, Beth-Shean and the towns in the Plain of Acco as well. Excavations at Gezer and Beth-Shean have confirmed the Biblical tradition that these cities remained Canaanite until the end of Israelite I. However, in the valley of Jezreel, Taanach and Megiddo were conquered in the third quarter of the 12th century. Both were destroyed about 1,125 B.C. Taanach remained unoccupied until the founding of a new Israelite city at the end of the 11th century. The last Canaanite city at Megiddo (Stratum VII A) was also destroyed about 1,125 B.C. On top a new settlement (Stratum VI) was built, entirely different from the Canaanite city.

The new settlement at Megiddo was an open village without fortifications. All the Canaanite public buildings that had stood for centuries disappeared, including the royal palace, the gate, and the temple tower that had been erected back in Middle Canaanite II. In their stead simple private structures were built; the pillared buildings are immediately prominent. The fate of the temple is clear evidence of a radical change and can only be interpreted as the arrival of a new population. Temples and high places in the “sacred area” had been built and rebuilt in Megiddo for nearly 2,000 years, from the beginning of the Early Bronze period down to Stratum VII A, in spite of all the destructions and alterations that took place in the city. This tradition was thoroughly broken, however, with the destruction of Stratum VII A, and thereafter no shrine is found in that area.

Some scholars maintain that Stratum VI at Megiddo remained Canaanite. This conclusion is based on the variety of vessels found there which are not found in the Israelite hill settlements but are, rather, part of the Canaanite ceramic tradition. It does not follow, however, that the ethnic composition of this stratum of Megiddo was Canaanite. Commerce among various parts of the country had already begun to flourish. The occupants of Megiddo no doubt traded with the Canaanite cities in the neighboring coastal area. In fact, we know they did so from pottery discovered in the Israelite settlements in the Negev. On the other hand, the many Israelite types of pottery so profuse in Megiddo VI argue against a continuation of the Canaanite population. It is inconceivable that the Canaanites would have suddenly introduced these crude and simple vessels in place of the finer ware to which they were accustomed.

In the final analysis, the decisive factor arguing for the Israelite character of the Stratum VI settlement is the typical Israelite nature of this village that contrasts with the Canaanite city with its fortifications and public buildings. This theory is supported by the unequivocal testimony of Taanach, which was destroyed along with Megiddo VIIA and abandoned for a long period of time. It is clear that the list in Judges 1 predates these two destructions and that the central area of the Jezreel valley had become Israelite by the end of the 12th century. By that time most of the Canaanite regions had been conquered. The only area that held out in the face of pressure by the Israelite tribes was the coastal plain, where the Philistines were located in the south and the Canaanites were located in the north.

This process of settlement and expansion went on for more than 200 years, and in its wake a mighty population revolution was brought about, unparalleled in the history of 020the country. Settlement of the hill regions increased appreciably and population there became dense. Geographical occupation gaps in various parts of the country closed. For the first time, the occupational center of gravity passed from the valleys to the hill country. The hill country remained the center of Israelite life until the end of the Israelite monarchy.

The increase in settlements, the closing of geographical occupation gaps, and the transfer of importance to the hill regions completely changed the population map of the Land of Israel. This population revolution explains the ever-increasing power of the young tribes and provides a background for the first national unification of the country in its long history, which occurred with the establishment of the Israelite monarchy. The Israelite conquest was more than simply a new ethnic wave of people who settled in place of the local population. The Land of Israel, on the one hand, and Canaan, on the other hand, were different from each other, not only ethnically, but also geographically and communally. These critical differences help us to understand the deep and decisive break in the history of the land marked by the Israelite occupation.

The chief rival to the Israelite occupation of the land during the period of the judges was the Philistine nation, another people that had arrived only recently, bringing with them some outstanding innovations in material culture. The Philistines were one of the “Sea Peoples.” Egyptian sources provide detailed information about the “Sea Peoples.” Some of them, such as the Sherdanu, already appear as mercenaries in the armies of the major powers of the 14th century. The Philistines, however, first appear in the inscriptions of Ramses III (1,175–1,144 B.C.). Their massive invasion, which rocked the foundations of Egypt and its neighbors, is described in this Pharaoh’s inscriptions and reliefs at Medinet Habu, which are dated to about 1,190 B.C. The Sea Peoples are described as coming from “their islands,” that is, the isles of the Aegean Sea, Cyprus, and the coast of Asia Minor. The invasion of Sea Peoples was led by the Philistines and the Sikkels (tj-k-r). According to the reliefs, they came both from the sea in warships and by land with their wives and children in ox-drawn wagons. The accompanying text says that they obliterated the cities and kingdoms in Cilicia and northern Syria and reached Amurru, in northern Lebanon, which marked the southern border of the Hittite empire on the boundary of the Egyptian province of Canaan. Ramses III claims to have delivered a decisive blow against the Sea Peoples. This is not just empty bragging but is proved by the continuation of his rule in the land of Canaan, as indicated by his inscriptions and those of Ramses VI at Beth-Shean and Megiddo.

This situation raises two questions: If Ramses III smote the Sea Peoples on the border of Canaan in the area of Lebanon, how did the Philistines reach the territory which they finally settled on the southern coastal plain of the Land of Israel, and when did they conquer that area? We must not forget that the southern coastal plain was a center of Egyptian rule in Canaan and that Gaza, which became one of the Philistine capitals, was the administrative center of that Egyptian province.

The generally accepted answer is thus: Philistines reached this area a short time after the battle in which they were defeated by Ramses III. They were settled there at first as mercenaries in Egyptian service. This assumption is based upon an inscription from the reign of Ramses III (Papyrus Harris I) which summarizes his activities. After the narrative of his victory, Ramses adds that he brought many prisoners to Egypt, settled them in fortresses under an oath of allegiance to him and allotted them food rations. The theory is that some of them were also settled in Egyptian fortresses in Canaan, and that with the disintegration of Egyptian authority they became the masters of the country Archaeological evidence has not confirmed this theory This is another example of how difficult it is for scholars to abandon an accepted theory even when new discoveries 021contradict it unequivocally.

We know that in the Egyptian capitals there was no continuity between the Canaanite and the Philistine cites, as one would expect to find if a garrison force of Philistines became masters after Egyptian authority had been removed. In a small excavation at Ashkelon, a thick burn layer was discovered between the last Canaanite settlement and the next stratum containing Philistine ware. The evidence at Ashdod is even clearer. There, extensive excavations were conducted by Moshe Dothan and others. The last city of the Late Canaanite period at Ashdod ends with a burn level; then follows an intermediate phase from the beginning of Israelite I, which still does not contain Philistine ware. Instead it contains Mycenean pottery from a period before the Philistines.

Philistine pottery is very homogeneous. Most of the forms and decorations are borrowed from the Mycenean world. The vessels include three Mycenean forms and a bowl with horizontal handles, a stirrup jar with a closed mouth and an open spout, and a pyxis with small horizontal handles. The vessels are characterized by a white slip upon which is a decoration, generally bichrome red and black, with geometric forms such as a spiral, semicircles, crosses, lozenges, and checkerboards. A bird motif with the head usually turned backward, peeking among its feathers, is commonplace. These themes are also found on jugs with strainers, which have been interpreted as vessels for drinking beer.

The Philistine ware is so homogeneous in quality, in material, in form and in decorative patterns that one must assume it was manufactured in a limited number of workshops in one area. There is no doubt that the workshops were Philistine; this pottery of obvious Mycenean origin makes its sudden appearance precisely at the time the Philistines settled in the area, and its geographical distribution is centered in Philistia. It is ubiquitous in all the sites from Israelite I in that area, and becomes gradually rarer as one moves away from that territory.

Philistine ware was derived not from the classic Mycenean ware which existed down to the end of the Mycenean kingdom (Mycenean IIIB), but rather from the second phase of sub-Mycenean pottery, a degenerate ware that had lost its classical uniformity and standard quality (Mycenean IIIC 1b). On this there is complete agreement among scholars. The best comparison is found on Cyprus, which the Philistines may have passed through on their way to Canaan.

The derivation of Philistine pottery from a sub-Mycenean repertoire presents a profound chronological implication, that Philistine occupation of Philistia could not have begun in the reign of Ramses III.

A certain period of time must have elapsed after the Philistine battles with Ramses III and their settlement in Philistia. No doubt Ugarit and Alalakh were destroyed by the early invasion of Sea People in the 12th century (approximately the end of the Mycenean kingdom and the end of classical Mycenean ware [Mycenean IIIB]). The excavation results from Ashkelon and Ashdod, especially the intermediate level at Ashdod between the stratum with Mycenean ware and that with Philistine pottery, indicates that a somewhat later date must be fixed for the appearance of the Philistines in Philistia on the coast of the Land of Israel.

The same sequence was established by Albright at Tell Beit Mirsim: After the last Canaanite stratum with Mycenean pottery (C2), there is a period of temporary occupation (B1), and only then a level with Philistine ware (B2). It is obvious, therefore, that the Philistine pottery did not arrive in the country before the middle of the 12th century. Hence, it is clear that the Philistines were not settled by the Egyptians; in fact, after the collapse of Egyptian authority, the Philistines replaced the Egyptians as rulers of the area that was to become Philistia. Moreover, the Philistine assumption of power must have occurred about 30 to 40 years after the Philistines were defeated by Ramses III. There is only one other possible explanation for the archaeological evidence; some scholars have preferred this other explanation, but it does not hold water. It is that the Philistines themselves came earlier but were followed only 30 or so years later by a family of potters who brought with them the ware we know as Philistine. This is hardly an attractive hypothesis.

We have no information about the Philistines’ invasion of the area on the Mediterranean coast known as Philistia, but as indicated above, we know it must have occurred. Since they first seized the harbor cities on the southern coast of the Land of Israel, they must have come in ships. The Egyptian narrative of Wen-Amon, dating to the beginning of the 11th century, records a Philistine fleet and Philistine domination of the coast. The Wen-Amon scroll also tells of another Sea People, the Sikkels (tj-k-r), who had taken over Dor, one of the coastal cities of the Land of Israel. The Sikkels had a fleet of ships that took them to the cities of Phoenicia, to Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos.

In another Egyptian document, the Onomasticon of Amenemope, from about the same time, we find a list of names: Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gaza and then Asher …, Sherdan, Sikkel, and Phileshet. These are first, the three main Philistine coastal cities; then the Israelite tribe of Asher which had settled in the plain of Acco; and finally three of the Sea Peoples (the last being the Philistines). 022From this it would seem that the Sherdanu, like the Sikkels and Philistines, had also taken over a certain section of the Palestinian coast.

Since the Philistines had taken the southern coast and the Sikkels were in the northern Sharon, it is likely that the Sherdanu had settled in the southern plain of Acco. Indeed, at Tell Abu Huwam, an ancient harbor city at the mouth of the Kishon north of the Carmel, excavated by R. W. Hamilton, a stratum confirms this assumption. This settlement was founded in Late Canaanite. Stratum V is very rich in Mycenean and Cypriot imports and was destroyed at the end of Late Canaanite in about 1,200 B.C. On its ruins a new settlement was established (Stratum IVA) with a type of architecture unique in the Land of Israel: rectangular houses divided symmetrically into three or four rooms. It is clear that these were new occupants, strangers to the country who had lived there only a short time. In the following settlement (Strata IVB-III), which was established after the destruction of those houses, there is an entirely different architecture, the typical Israelite pillared houses.

In the limited excavations conducted at Dor and in the extensive excavations at Tell Abu Huwam, no Philistine pottery was found. From this evidence it seems probable that these were not Philistine settlements. Could the intermediate foreign stratum at Tell Abu Huwam, between the Canaanite and the later (Israelite?) town, be the harbor town of the Sherdanu mentioned in the Egyptian Onomasticon?

The Philistines were the dominant force among the Sea Peoples who gained a foothold in the Land of Israel. Eventually they gave their name to the entire country: Palaestina, Palestine. They settled on the southern coastal plain, one of the most fertile and well-developed areas of the country where Egyptian authority in Canaan had been centered.

The Philistines’ three main coastal cities were Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod, all of which had also served as important seaports in the Late Canaanite period. When the alliance of Philistine lords confronted the Israelite tribes in the mid-11th century, it was led not only by the three coastal cities but also by two more cities farther east in the Shephelah—Gath and Ekron.

Judging by the influence of Mycenean culture on Philistine cult vessels, it seems practically certain that the Philistine pantheon originated in the Aegean world. However, these Philistine deities were soon assimilated into the great Semitic divinities of Canaan, whose names and characteristics were applied to the Philistine pantheon. All of the names we know from the Bible are of familiar Canaanite deities, for example, Dagon, the god of grain and agricultural fertility, and Baalzebub, a transparent corruption of Baal-zebul. This process is characteristic of the Philistines in general: In spite of their strong military force and their efficient organization in the pentapolis alliance, they rapidly assimilated the material and cultural milieu of Canaan, leaving only a residue of their Aegean origins. This is as true in Philistine pottery as it is in the Philistine cult. Even before the middle of the 11th century, Philistine ware had actually ceased to exist. It was produced for only a few generations from the middle of the 12th to the beginning of the 11th century; its brief existence thus makes it an excellent chronological indicator.

The Philistines brought with them burial customs from the Aegean. A rich collection of anthropoid coffins at Deir el-Balah, south of Gaza, with distinctly Egyptian objects, makes it clear that these anthropoid coffins (with humanoid covers) reflect an Egyptian burial custom. (See “Excavating Anthropoid Coffins in the Gaza Strip,” BAR 02:01.) It is also clear that the use of anthropoid coffins was widely adopted by the Sea People mercenaries who served in the Egyptian fortresses. This conclusion is further supported by the anthropoid burials at Beth-Shean. The grotesque faces are far removed from their Egyptian prototypes: headband ornamentations are reminiscent of the feathered helmets of the Philistines, the Sikkels, and the Danunians on the reliefs from Medinet Habu. In one of the Beth-Shean tombs an oval plate attached to the mouth of the deceased was found, similar to well-known examples from Mycenae.

Although the anthropoid coffins at a number of sites such as Beth-Shean, Tel Sharuhen, and perhaps at Lachish evidently belonged to mercenaries from among the Sea Peoples stationed at Egyptian forts, this does not contradict the assumption that the Philistines did not first come to occupy their own territories as Egyptian mercenaries. Lachish, Tel Sharuhen, and, in particular, Beth-Shean were distinctly Egyptian strong points. Moreover, the burials at Beth-Shean and Lachish apparently preceded the Philistine occupation of Philistia.

The size of the Philistine towns, the density of population in these areas, and the appreciable diffusion of Philistine ware leave no room for doubt about the intensity of the Philistine influx, even though some of the former Canaanite population perhaps nevertheless remained under the yoke of the new Philistine rulers. It is also clear that the Philistines brought with them a well-developed tradition of urban society, an efficient confederated organization, and a high level of military technology on sea and land. It is no wonder that their territory soon became too confining, and they expanded into the Shephelah, where they encountered the Hebrew tribes. This encounter expressed itself both in military conflicts and in commercial and familial 023relationships that are clearly manifest in the narratives about Samson from the beginning of the 11th century.

The fateful conflict between Israel and the Philistines began in the mid–11th century and continued for about 50 years, to the beginning of David’s reign. These two vigorous peoples were now like coiled springs, planted in their respective areas, both looking for additional territories for their surplus population. Initially, the Philistines had the upper hand, because of their superior military and administrative organization. But as soon as the Israelite monarchy was established—in particular, when it was headed by a military and political leader of David’s stature—the balance was quickly tipped in Israel’s favor. There was no comparison between the population potential of Israel compared to that of the Philistines in their limited territories. From this standpoint alone, there was no doubt who would be victorious in the struggle for the inheritance of the land of Canaan. Henceforth, the Philistines had to content themselves with their restricted, albeit important, area, Philistia, on the southern coast of Canaan, an area from which they never again tried to break out.

During the period of Philistine ascendancy in the second half of the 11th century, the Israelites may have borrowed certain achievements in material technology and in military and administrative organization from the Philistines. The revolutionary change in Israelite material culture began, however, only during the tenth century, and the predominant sources of influence were Syria and Phoenicia. Until the end of the 11th century the Israelite population continued with its simple, homogeneous culture with very few innovations.

This article is adapted and excerpted from chapter IV of The Archaeology of the Land of Israel: From the Prehistoric Beginnings to the End of the First Temple Period, by Yohanan Aharoni, edited by Miriam Aharoni. Translated from the Hebrew by Anson F. Rainey. (© 1978 Shikmona Publishing Company Ltd.) (Translation © 1981 The Westminster Press.) Used by permission.

The archaeological time period known as the Iron Age—or the Israelite period, as I shall call it here—began in about 1,200 B.C. and lasted for about 600 years. In the Land of Israel, it ended with the destruction of the First Temple in 587 B.C. Scholars generally agree that the penetration and settlement by the Israelites into the various regions of the country began, at the latest, in the 13th century B.C. As I shall show, it quite probably began, in fact, in the 14th century. Thus the period of the “conquest” began in the Late Canaanite period, that […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username