The Southern Sinai Exodus Route in Ecological Perspective

027

Tradition locates quite precisely in southern Sinai a number of places associated with the Israelites’ history: the burning bush where Moses heard God’s call (Exodus 3:2–4), identified with a raspberry plant growing in the yard of St. Catherine’s Monastery; Horeb, where the prophet Elijah found refuge (1 Kings 19:8), identified with Jebel Sufsafeh next to Jebel Musa; the hill where the Israelites worshipped the golden calf, with Nebi Haroun one kilometer west of St. Catherine’s; and, above all, Mt. Sinai, with Jebel Musa, which rises in all its glory above St. Catherine’s Monastery.

During the latter part of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries—in what we might call the pre-archaeological-research age—two principal theories developed concerning the route of the Exodus journey through Sinai. These theories were developed by scholars who traveled in Sinai and who based their conclusions both on Biblical textual evidence and on geographical evidence garnered during their journeys.

Some of these scholars argued for a southern route and others for a northern one. The proponents of the “northern theory” identified some of the sites mentioned in the Bible with places in northern Sinai and maintained that the children of Israel wandered in the expanses of that part of the peninsula. These scholars proposed to identify the Red Sea with one of the lagoons of the Mediterranean coast (for example, Sabh

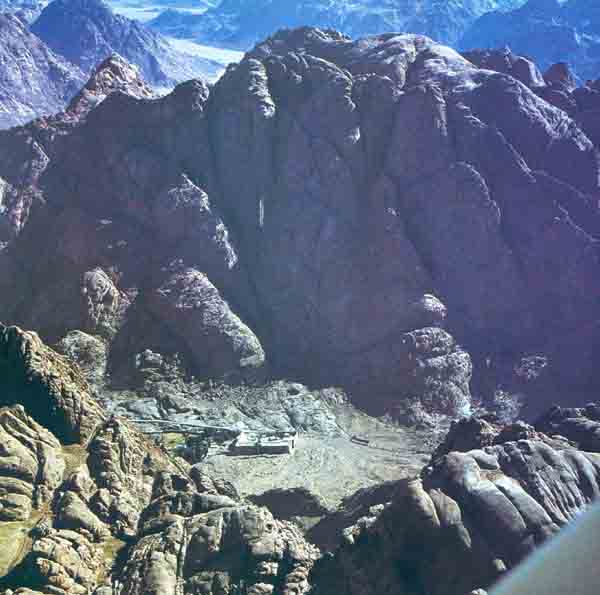

Proponents of the “southern theory” argued that the children of Israel crossed the remote and majestic region of southern Sinai on their way to the Promised Land. These scholars identified the encampments mentioned in the Bible with places in that region. Naturally, many of these scholars identified Mt. Sinai with Jebel Musa, rising high above St. Catherine’s Monastery, in the midst of the rugged granite massif.

In recent years archaeological research in the Sinai peninsula has burgeoned as never before. Intensive surveys and excavations have been carried out in all regions of the peninsula, and what was once a remote and mysterious wilderness has become, archaeologically speaking, well known and relatively well understood.1

All this archaeological activity, however, has contributed almost nothing to our understanding of the Exodus. This is true despite the fact that the Bible describes the wanderings of the Israelites at great length and even provides us with a long list of place-names where the children of Israel encamped during their wanderings (Numbers 33). But, so far, no remains from the Late Bronze Age (15th–13th centuries B.C.—the period in which these events were supposed to have taken place) or even from the subsequent Iron Age I have been found anywhere in the whole Sinai peninsula, except for archaeological evidence of Egyptian activity on Sinai’s northern coastal strip. Accordingly, no progress has been made in locating the Israelite encampments, in identifying their route, or in fixing the site of Mt. Sinai.

Since neither archaeological nor historical research has contributed to solving the puzzle of the route of Israel’s wandering or the location of Mt. Sinai, a new approach is justified. Our own investigations in the Sinai heights have prompted us to propose an ecological explanation for the pattern of monastic settlement in southern Sinai which, in turn, accounts for the identification of Mt. Sinai and numerous other “Biblical” sites in the area.

The traditional identifications of sites in southern Sinai appear for the first time in written sources in the Byzantine period.a Literary sources earlier than the Byzantine period are few and vague; they do not specify the location of Biblical sites in Sinai. Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian who provides detailed descriptions of the Holy Land, simply locates Mt. Sinai in Midian, east of the Red Sea. The New Testament (Galatians 4:25) locates it in “Arabia,” the general name for the deserts south of Palestine.

By contrast, pilgrims’ accounts from the fourth to sixth centuries A.D. are quite specific. In the late fourth century, a devout woman named Egeria came from the Atlantic coast of Western Europe to visit Palestine, Sinai and Egypt. Here is part of the account of her visit to Mt. Sinai:

“I began to ask [the monks] to show us the several localities. Thereupon the holy men deigned to show us each place. For they showed us the famous cave where holy Moses was when for the second time he went up to the Mount of God to receive the tables [of 030the law] … and the other places also which we desired to see or which they knew better they deigned to show us … all which things those holy men pointed out to us … we began now to descend from the summit of the Mount of God to another mountain which is joined to it; the place is called Horeb, and there is a church there. This is that Horeb where was the holy prophet Elijah … For the cave where holy Elijah hid is shown to this day … All which things the holy men deigned to show us. There we offered an oblation and an earnest prayer, and the passage from the book of Kings was read; for we always especially desired that when we came to any place the corresponding passage from the book should be read … we went on to another place not far off, which the priests and monks pointed out, that place where holy Aaron had stood with the seventy elders … The passage from the book of Moses was read … and then, having offered a prayer, we descended … We arrived at the Bush … This is the Bush I spoke of above, from which God spake to Moses in the fire … prayer was offered in the church, and also in the garden at the Bush; also the passage was read from the book of Moses as usual … And they showed us the place where the children of Israel lusted for food … They showed also that place where 032it rained manna and quails. In fine, everything recorded in the holy book of Moses as having been done in that place, to wit, the valley which I said lies under the Mount of God, holy Sinai, was shown to us … ” (Egeria’s Travels to the Holy Land, 3.7–4.6)2

The Piacenza pilgrim (Antoninus the Martyr), who visited the region about two centuries later, is similarly specific:

“Going on through the desert we arrived on the eighth day at the place where Moses brought water out of the rock. A day’s journey from there we came to Horeb, the Mount of God … At the foot of this 033mountain is the spring where Moses saw the miracle of the burning bush and at which he was watering the sheep. This spring is within the monastery walls. … ”

In stark contrast to the uncertainty that characterizes modern research into the identification of these places, Byzantine monastic traditions located these sites precisely and with certainty. Did the Sinai monks have sources of information that have since disappeared? A more likely possibility is that the traditions of sanctity connected with the Sinai heights were developed contemporaneously with the process of monastic settlement in the region. This process, in turn, was the result of the favorable subsistence conditions of the area, and was probably inspired by the awesome beauty of the mountains.

The Byzantine age saw the birth and floruit of monasticism. Thousands of monks spread all over the deserts of the eastern Mediterranean, from Asia Minor in the north to upper Egypt in the south. In the Holy Land, Byzantine monastic remains are known especially in the Judean wildness and in the Negev. Various reasons led to the development of this phenomenon. When monasticism began in the late Roman period, religious oppression was a main stimulant of the movement. Later, when Christianity became the ruling faith, there were other stimulants, such as economic crises and disappointment in both religious and secular imperial establishments.

By the fourth century, large monastic communities were already established in Sinai. It was then, for example, that a small chapel commemorating the site of the burning bush was erected at the site where St. Catherine’s Monastery now stands. Sinaitic monasticism reached its greatest development in the sixth century, during the reign of Emperor Justinian. It was Justinian who built the fortress around the monastery of the burning bush, as well as the church inside.b

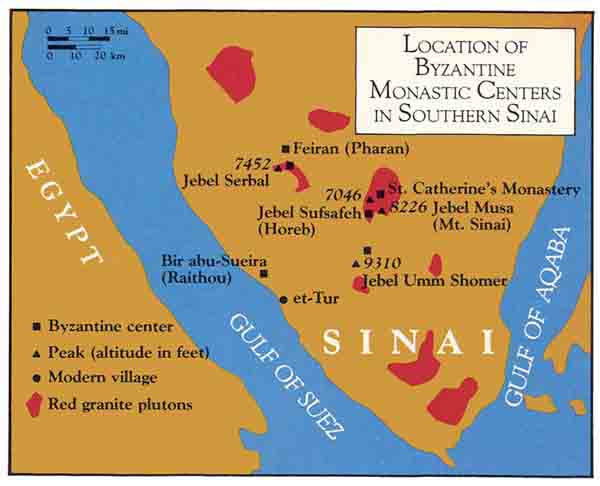

But even at the height of the monastic movement, monks did not occupy the whole of the Sinai peninsula. Indeed, the monastic communities did not even occupy all parts of southern Sinai. There were in fact five monastic centers in the region (see map). The largest and most important was in the area around St. Catherine’s, where many monastic communities lived in small valleys, or wadis, between the impressive peaks. Recent surveys have uncovered the remains of these communities—small monasteries, chapels, desert orchards, water installations and paved paths.

Two additional southern Sinai mountain ridges—Jebel Serbal and Jebel Umm Shomer—contain the remains of Byzantine monastic occupation. The large and impressive massif of Jebel Serbal rises high above the oasis of Feiran. Jebel Umm Shomer is a wild, rugged and remote mountain in the southwestern part of the peninsula.

034

A fourth center of monastic activity was located in the great oasis of Feiran (Pharan in the Byzantine sources), identified by the monks as Rephidim, where the Israelites battled against Amalek (Exodus 17:8). Remains of a number of churches and chapels of the Byzantine period were found on a tell in the center of the Feiran oasis and on the adjacent mountain that looks down on the oasis.

The fifth center of Sinai monasticism was at et-Tur on the coast of the Suez Gulf (Raithou in the monastic sources). This center served as a sea gate for those coming to southern Sinai from Upper Egypt. North of the modern village of et-Tur, in the vicinity of a small picturesque oasis known as Bir abu-Sueira, various monastic remains are known.

Why were the monastic settlements in southern Sinai located only in these five areas? At et-Tur, there were obvious economic and geographic reasons—it was a port from which several camel tracks led to Mt. Sinai. The Feiran oasis, the largest in southern Sinai, has always been a favored site of human activity, and the Byzantine period was no exception.

The location of the other three monastic centers can be accounted for mainly on ecological grounds. Southern Sinai has a desert ecosystem that is characterized by high 035temperatures, low humidity and very little precipitation. Few areas in southern Sinai get more than two inches of rain in an average year.

Many of the rugged mountains of southern Sinai are composed of plutonic rock, which was formed by the solidification of molten lava deep within the earth and is crystalline throughout. Most of this plutonic rock is grey granite. In a relatively few places, including the vicinity of St. Catherine’s, Jebel Serbal and Jebel Umm Shomer, this plutonic rock is exposed in the form of red granite. This red granite, we suggest, is the key to the monastic settlement patterns. As the map indicates, the monastic centers in the areas around these three mountains were established on red granite plutons; that is, where the red granite was exposed.

Another important factor is that these monastic centers are all situated relatively high up—4,000 to 6,500 feet above sea level. There are, of course, high ridges in southern Sinai where no red granite is exposed. But on these ridges we found no Byzantine remains. Moreover, red granite is sometimes exposed at elevations of less than 4,000 feet, but at these sites too there are no Byzantine remains. In conclusion, all the monastic communities in the Sinai heights are located between roughly 4,000 and 6,500 feet above sea level, where red granite is exposed.

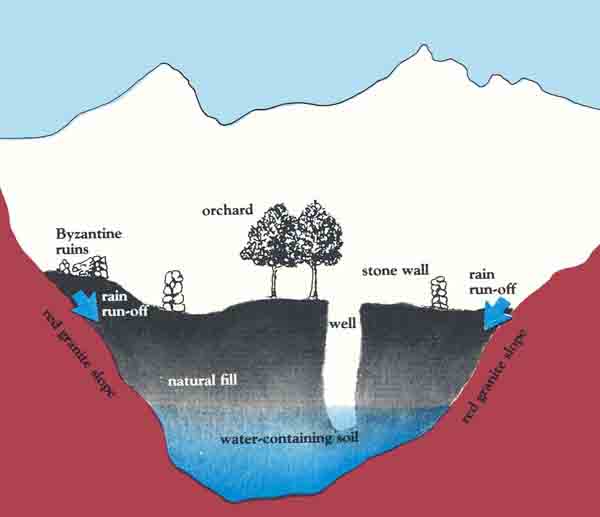

The reason for this interesting phenomenon lies in the unique combination of the qualities of red granite and the climate in the high mountains. The principal factor in this ecological framework relates to the nature of the red granite: It creates large, non-porous surfaces, so that even very limited precipitation leads to significant run-off. Thus a small amount of rain falling over a large area on the mountain slopes provides considerable quantities of water that reach the relatively small areas of lower ground, creating there a very rich water table (see plan). It is interesting to note that the wadis of the red granite area enjoy an actual water economy equivalent to approximately 15 inches of precipitation, while only about two inches fall directly on the rock surfaces. Good alluvial soil is also deposited in these areas. As a result we find in this region a particular type of agriculture, orchards, which are not feasible in other desert areas. These orchards can support a considerable sedentary population.

The red granite mountains provide subsistence opportunities even today. The Bedouin population of the Sinai heights, mostly from the Jebeliyah tribe, supports itself in large part from fruit orchards and small vegetable gardens 038in the deep, narrow wadis between the high mountains. The produce of the average orchard, together with a flock of goats, can easily provide subsistence for a Bedouin family. The family consumes part of the produce and trades the remainder in Sinai or sends it to the markets of Egypt.

In our survey of this high mountain area, we found more than 400 orchards, 95% of them in wadis that cut through the red granite. The average orchard (see table) covers a mere half-acre and contains 13 grapevines, 11 almond trees, 4 or 5 apple, pear, apricot, pomegranate and fig trees, perhaps a few plum, quince and peach trees, and sometimes even a date palm—altogether about 50 trees. Each orchard also contains a vegetable garden where, typically, tomatoes, beans and corn are grown. A strong stone wall usually surrounds the orchard, protecting it from wadi floods and goats. The plots for the vegetables, as well as for the fruit trees, are created on the sloping land with the help of stone terraces.

035

Composition and Annual Yield of an Average Bedouin Orchard in the Sinai Heights |

||

| Species of Fruit | Number of trees |

Production in pounds |

| Grape | 13 | 123 |

| Almond | 11 | 156 |

| Apple | 5 | 145 |

| Pear | 4.5 | 330 |

| Apricot | 4 | 146 |

| Pomegranate | 4 | 134 |

| Fig | 3.5 | 121 |

| Plum | 2.75 | 138 |

| Quince | 2 | 297 |

| Peach | 1 | 33 |

| Total | 51 trees | 1623 pounds |

| Each orchard also contains a vegetable plot with an area of approximately 600 square feet. |

At least one well is found in each orchard. The water from the well is drawn up to a storage pool and from there is channeled to the cultivated plots. On the side of the orchard there is usually a structure where the Bedouin live in the summer, the agricultural peak season. The structure may also serve for storage.

The desert orchard agriculture of the local Bedouin is the heritage of the Byzantine period, when intensive agricultural settlements were first established in this region. Our archaeological surveys show clear connections between the Bedouin orchards and Byzantine predecessors. In many cases, the Bedouin orchards use the early remains; in other cases, we find the ancient ruins alongside the present-day orchards.

The Byzantine orchard was similar to the contemporary Bedouin one, except that in many places remains of monasteries or small farmhouses were found next to the 039plot. From a quantitative point of view, it is clear that there are more early orchards than contemporary ones. In short, agricultural activity and settlement in the high mountain areas of southern Sinai were more extensive and developed in the Byzantine period than they are today. Many Byzantine agricultural settlements were discovered in areas too inhospitable for the Bedouin—for example, in the heights of Jebel Serbal, and on the remote slopes of Jebel Umm Shomer. Needless to say, all these sites are located in red granite areas.

Byzantine literary sources sometimes reflect this intensive agricultural activity. For example, Egeria tells us:

“As I was passing out of the church the priest gave us gifts of blessing from the place; that is, gifts of the fruits grown in the mountain. For although the holy mountain of Sinai itself is all rocky, so that it has not a bush on it, yet down near the foot of the mountains—either the central one or those which form the ring—there is a little plot of ground; here the holy monks diligently plant shrubs and lay out orchards and fields; and hard by they place their own cells, so that they may get, as if from the soil of the mountain itself, some fruit which they may seem to have cultivated with their own hands.” (Egeria’s Travels to the Holy Land, 3.6.)

We do not mean to imply that the red granite rock alone accounted for the location of monastic settlements. Several factors joined together to make Sinai a magnet for a large monastic movement in the Byzantine period. The distance and isolation of the peninsula, far from the centers of Roman imperial rule, provided a refuge for the body, as well as a haven for the soul. Here one could be free both from religious oppression and from the temptations of the world. The power of the sublime landscape with its mountains—colorful, precipitous, wild and rugged—surely affected the ancients, as it does us. This setting undoubtedly inspired religious feelings that well suited the world of the monks and their ideas concerning the closeness of man to God.

But in the end, it was the ecological factor that proved crucial. Only the red granite, exposed in the wadis and valleys, allowed the intensive agriculture that supported the monastic communities. Were it not for the altitude, which makes the desert climate relatively comfortable, and the special qualities of the red granite, such a strong monastic movement could never have grown up in southern Sinai. In this same region, with the same landscape, but without this particular rock, there would be insufficient water for permanent settlements. And, at a lower altitude on the same rocky slopes, it was too hot and there was too little precipitation, permitting only migratory husbandry as the sole mode of subsistence.

Local economic and geographical factors also affected the distribution of the monastic communities. The main routes leading to “Mt. Sinai” from Egypt (via Pharan and via the Umm Shomer region) attracted monks to these vicinities. There was also a process of settlement expansion from the monastic centers. The area around the Monastery of the Burning Bush became more and more densely settled, leading to the establishment of new monasteries in more distant and remote areas preferred by more reclusive monks.

The monastic communities are probably the sources of the traditions locating Biblical sites in southern Sinai, especially in the area of St. Catherine’s Monastery and near the springs of the Feiran oasis. Many Biblical sites located around the monastery lie close to one another, despite the fact that the Bible itself gives no indication of their proximity. Thus, the site of the burning bush, the site where Moses struck the rock that yielded water, the hill on which God first spoke to Moses, and the hill on which Aaron built the golden calf, are all identified within an area of approximately two square miles immediately around Jebel Musa, Mt. Sinai in the monastic belief.

In this context, it is also interesting to note that a traveler named Cosmas Indicopleustes, who visited the Sinai Peninsula in the middle of the sixth century A.D., locates Mt. Sinai six miles from Feiran. He is probably referring to Jebel Serbal, an impressive red granite massif that rises almost vertically above the Feiran oasis, and in which there are Byzantine monastic remains. Most scholars consider Cosmas’s identification an error, or the result 041of a misunderstanding; however, there may well have been at that time other traditions identifying Biblical sites in other red granite monastic areas, such as Jebel Serbal and Jebel Umm Shomer. The evolution of such traditions may have been connected with the growth and expansion of the monastic settlements to other red granite massifs.

It is, of course, possible that traditions regarding sacred sites existed before the monastic settlements. A more likely scenario, however, is that the traditions identifying Biblical sites in southern Sinai developed hand in hand with the growth and development of the large monastic centers. Out of these traditions the theory of the southern route of the Exodus was born.

Yet, the Byzantine pattern of monastic settlement was dictated by ecological considerations: The only environment that enabled non-nomadic subsistence in the harsh desert was the wadis of the high mountain valleys where the red granite was exposed. The superior subsistence potential in this remote region attracted the monks. At the same time—probably from the beginning of Byzantine monastic activity—the monks began to designate various sites in their vicinity as places in which the exalted events described in the Bible took place.

The sacred sites the monks identified—no doubt stimulated by the awe-inspiring beauty of the majestic scenery—soon became the goals of pilgrims from all over the Mediterranean. Highly motivated religious travelers described the sites, and, as time passed, their geographical locations became unquestioned. If the red granite had not been exposed in these wadis, however, Jebel Musa might never have been identified as Mt. Sinai.3

Tradition locates quite precisely in southern Sinai a number of places associated with the Israelites’ history: the burning bush where Moses heard God’s call (Exodus 3:2–4), identified with a raspberry plant growing in the yard of St. Catherine’s Monastery; Horeb, where the prophet Elijah found refuge (1 Kings 19:8), identified with Jebel Sufsafeh next to Jebel Musa; the hill where the Israelites worshipped the golden calf, with Nebi Haroun one kilometer west of St. Catherine’s; and, above all, Mt. Sinai, with Jebel Musa, which rises in all its glory above St. Catherine’s Monastery. During the latter part of the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

The Byzantine period begins in the Holy Land, Egypt and Sinai in 324 A.D. and ends in the seventh century with the Moslem conquest.

The monastery did not become known as St. Catherine’s Monastery until the 11th century. Originally, in the sixth century, Justinian had dedicated the church he built in the enclosure of the monastery to the Virgin Mary. St. Catherine was a martyr who had upbraided the Roman Emperor Maximinus for persecuting Christians. The emperor retaliated by beheading her. Her body and severed head were said to be miraculously transported by five angels to a peak near the Justinian monastery. Legend held that the angels watched over the priceless relics (her bones) for several hundred years, until their presence was revealed to the monks of the monastery, who joyfully carried her bones to their church and renamed the monastery in her honor.

Endnotes

See Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, “Fifteen Years in Sinai,” BAR 10:04.

See A. Thomas Kraabel, review of Egeria’s Travels to the Holy Land, ed. and transl., John Wilkinson, Books in Brief, BAR 09:02.

This article is based on studies of the subsistence patterns of the Jebeliyah Bedouins by Aviram Perevolotsky and of the Byzantine remains in the vicinity of St. Catherine’s Monastery by Israel Finkelstein. Both works were undertaken by the Tzakei David Field School of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (S.P.N.I). The authors would like to thank Judith Dekel for her drawings adapted on pp. 35, 37, 39 and the S.P.N.I. for financial support.