In the preceding article Phil King and Larry Stager explain that the Hebrew term ‘ebed, literally “servant,” can designate anything from a slave or household servant to a high royal official, a servant of the king. The same is true in English of terms like “secretary,” which can mean anything from someone who assists with correspondence and files to a member of the President’s cabinet—such as the secretary of state.

Just as “cabinet secretary” does not designate a particular high government official, however, so it was in ancient Israel with “servant of the king,” which indicated membership in an elite group and not a specific office.1 This is shown by the use of the plural (“servants of the king”) in the Bible to designate the ranking members of the royal court. For example, after the prophet Nathan anoints David’s son Solomon as king, Solomon takes the throne and ‘abdê hammelek, “the servants of the king,” come to give David their blessing (1 Kings 1:47). While the literal translation is “servants of the king,” the New Jewish Publication Society translation renders the phrase “courtiers;” the New English Bible calls them “the officers of the household;” and the New Jerusalem Bible has “king’s officers.” All of these translations reflect the fact that the singular “servant of the king” is not a title of a particular office, but indicates membership in the king’s inner circle.

Similarly, more than 200 years later, when an Assyrian deputation threatens King Hezekiah and advises surrender, Hezekiah sends Eliakim, “who is over the house,” as well as Shebna the scribe and the senior priests to the prophet Isaiah for advice (2 Kings 19:2). This group is then referred to as ‘abdê hammelek h

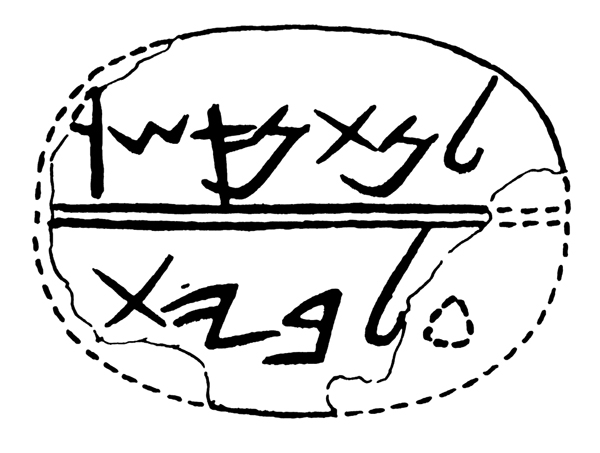

We have a number of ancient Hebrew seals and bullae (a bulla is a lump of clay with a seal that once sealed a document) whose owners are identified by the title “servant of the king,” indicating that they were members of this inner circle of royal “servants.” A recently surfaced bulla impressed with the seal of one such “servant” is especially intriguing because it is probable that he is actually mentioned in the Bible. The light brown clay bulla bears the imprint of a seal consisting of two lines of expertly inscribed Hebrew letters of the late seventh century B.C.E., the time of King Josiah of Judah, best known for his religious reforms (see 2 Kings 22–23). As is characteristic of Hebrew seals of this period,2 this one is aniconic; the only engraving on it other than the letters is a double line dividing the inscription into two registers and a similar double line that, to judge from comparable seals and bullae,3 surrounded the letters as a border. In this case the seal was not pressed deeply enough into the clay to show the complete border, which is visible only on the upper edge of the impression.

The two-line Hebrew inscription reads:

klmntnl Belonging to Nathan-melech,4

[k ]lmh db[ the servant of the king.

At least 14 seals or seal impressions are known that identify the owner as a “servant of the king.”5 This designation has also been found on a Hebrew ostracon from Lachish.6 But only one person is individually and singularly named in the Bible as a “servant of the king.” He is a certain Asaiah who was a member of the delegation appointed by King Josiah to consult with Hulda the prophetess about “the Book of the Law” found in the Temple (2 Kings 22:12; 2 Chronicles 34:20). This book is generally believed to be an early version of Deuteronomy.

Nathan-melech, the name on our bulla, is not a common Hebrew name. As I mentioned, only one person in the Bible bears it, and he is probably the same person who owned the seal impressed in our bulla. The Biblical Nathan-melech is an officer at King Josiah’s court (2 Kings 23:11), but in the Bible he does not bear the designation “servant of the king.” Instead he is called “sa

Why then do I think that Nathan-melech, the “eunuch,” is the same Nathan-melech, the servant of the king, who owned the seal impressed in our bulla? Essentially, it is the coincidence of three facts: 1) The rarity of the name Nathan-melech, 2) the fact that both Nathan-melechs can be placed in the latter part of the seventh century B.C.E. and 3) the fact that both men of the same rare name served in high positions at the court of King Josiah.

As to the rarity of the name: Nathan-melech, like other Hebrew names, means something; it is, in effect, a condensed sentence. The first part of the name, na

The compound ne

Inscriptions like this can be dated paleographically. The form and stance of the letters change over time (just as the shape of pottery changes over time) and often provide a reliable basis for dating an inscription. The changes in Hebrew letter forms in the eighth to sixth centuries B.C.E. are well known. For this reason, the difference, let us say, between an inscription from the reign of King Hezekiah in the late eighth century B.C.E. and a similar inscription from the reign of King Josiah in the late seventh century B.C.E. is not difficult for an experienced paleographer to recognize. Take, for example, the Hebrew letter he

Based on the paleography of our bulla, we can date it to the late seventh century B.C.E., the time of Josiah. We know from the Bible that a man named Nathan-melech served in a high position in Josiah’s court at this time. From the title “servant of the king” that appears on our bulla, we know that the Nathan-melech to whom it belonged was also a high court official, most probably in the administration of King Josiah. Could there have been two men with this same unusual name serving in elite positions in King Josiah’s court? Possibly, but it seems unlikely. That’s why I believe that the two men are one and the same, and that our bulla is impressed with the seal of the Biblical Nathan-melech. True, Nathan-melech is called a “eunuch” in the Bible, while he is only identified on the bulla as a “servant of the king.” But as already explained, the latter identification indicates only that he was a member of an elite group of high officials, not the holder of a specific office. The Biblical eunuch would also be a “servant of the king.”

If I may move from the probable to the speculative, it is possible that we have a second bulla impressed with a different seal of the same Nathan-melech. We know of another bulla of the same historical period inscribed “Belonging to Nathan, who is over the house” (lntn ’s

Unlike the designation “servant of the king” (which identifies an elite group), the designation “who is over the house” is the title of a single office. Though the responsibilities of this office probably varied with time, “(the one) who is over the house” seems to have been the title used from the earliest times for the senior administrator of the palace10—the royal steward—in both Judah and Israel, as indicated by its occurrences in the Bible11 and in the epigraphic record.b

Is the “Nathan who is over the house” in this seal the same person who is a “servant of the king” in the bulla of Nathan-melech? Could the man “who is over the house” be the same fellow as the “servant of the king” after he had been promoted to a more senior position? It’s possible, even though the names are somewhat different. In our bulla he is “Nathan-melech,” while in the seal of the steward, he is just “Nathan.” But in any case, “Nathan” had to have been a shortened form of his name, which would have been completed with the name of a deity. Which was it—El, Yahweh or perhaps Melech? If the last, we may have the seal of this gentleman at a later period in his life, when he had risen to the lofty position of royal steward.

A more detailed version of this article appears in Realia Dei (Edward F. Campbell, Jr., Festschrift), edited by Prescott H. Williams, Jr. and Theodore Hiebert (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1999). The bulla discussed here belongs to the collection of Shlomo Moussaieff of London. I am grateful to Mr. Moussaieff for permission to publish it. It has also been published by Robert Deutsch in Messages from the Past: Hebrew Bullae from the Time of Isaiah through the Destruction of the First Temple (Tel Aviv-Jaffa: Archaeological Center, 1999).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See “‘David’ Found at Dan,” BAR 20:02; Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand,” BAR 20:04; Anson Rainey, “The ‘House of David’ and the House of the Deconstructionists,” BAR 20:06; and David Noel Freedman and Jeffrey C. Geoghegan, “‘House of David’ Is There!” BAR 21:02.

See Hershel Shanks, “The Tombs of Silwan,” BAR 20:03.

Endnotes

This is the conclusion of most who have investigated the question. See, for example, Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Livonia, MI: Dove Booksellers, 1997) pp. 120–123.

There is now abundant evidence of the preponderant aniconism of Hebrew seals from the last century of the kingdom of Judah, at least in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Nahman Avigad, Ens

In his general description of the group of 255 that he was publishing, Avigad writes that “The great majority of the bullae bear two-line inscriptions, with a divider in the form of two parallel lines (often close together, comprising a double line)” (Hebrew Bullae, p. 18). With regard to the 49 intact bullae from the City of David hoard, Shiloh writes that “The most common divider, on 22 of the seal-impressions, consists of two plain, parallel lines” (“Group of Hebrew Bullae,” p. 27).

Since the name Nathan-melech appears in the Bible, I have rendered it with its customary English vocalization, which is based on the Massoretic form of the name, ne

These include the seals of “Obadiah, the servant of the king” (l‘bdyhw ‘bd hmlk; Nahman Avigad and Benjamin Sass, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals [Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Israel Exploration Society, Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1997], p. 53 [no. 9]), “Shema, the servant of the king” (Avigad and Sass, Corpus, p. 53 [no. 10]), “Jaazaniah, the servant of the king” (ly’znyhw ‘bd hmlk; Avigad and Sass, Corpus, p. 52 [no. 8]), “Gaaliah, the servant of the king” (lg’lyhw ‘bd hmlk; Avigad and Sass, Corpus, p. 52 [no. 7]), “Eliakim, the servant of the king” (l’lyqm ‘bd hmlk; Avigad and Sass, Corpus, pp. 51–52 [no. 6]), “Asaiah, the servant of the king” (l’s

The name “Tobiah, the servant of the king” (t

The chronology of this development is still not clear, however, and there is some evidence that castration was the rule for s

The office has been extensively discussed. See, for example, de Vaux, Ancient Israel, pp. 129–131; T.N.D. Mettinger, Solomonic State Officials (Coniectanea biblica Old Testament 5; Lund: CWK Gleerup, 1971), pp. 70–73.