The Christian Flight to Pella: True or Tale?

031

In 66 A.D., approximately 35 years after Jesus’ crucifixion, the Jews revolted against their Roman rulers, a revolt that ended in 70 A.D. with the burning of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple.

On the eve of its destruction, the followers of Jesus, later to be known as Christians, fled from Jerusalem to Pella on the other side of the Jordan River, according to the fourth-century church historian Eusebius of Caesarea:

“When the people of the church in Jerusalem were instructed by an oracular revelation delivered to worthy men there to move away from the city and to live in a city of Peraea called Pella, the believers in Christ migrated from Jerusalem to that place.”1

In 1967 Robert Houston (“Bob”) Smith of the College of Wooster, Ohio, initiated an archaeological excavation at Pella in the hope of finding evidence for this early Christian presence. Of course he also had many other questions about the site.

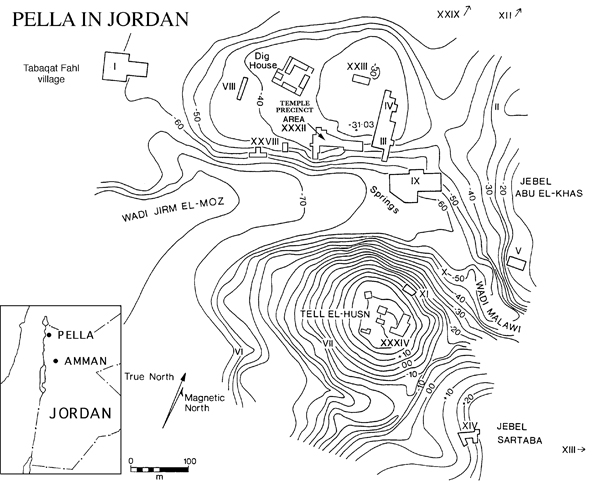

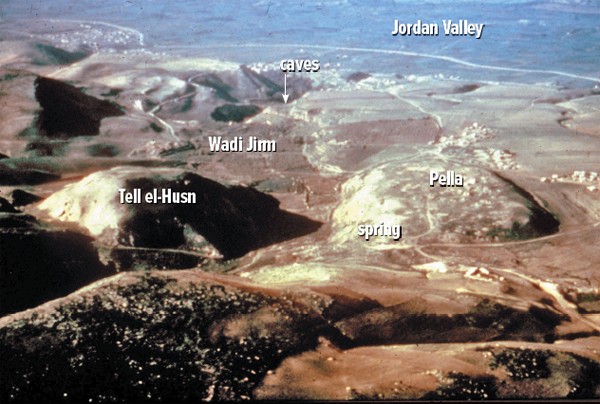

In addition to the 20-acre principal mound of Pella, a Civic Complex was constructed near the foot of the mound that extends into the Wadi Jirm. On the other side of the wadi rises Tell el-Husn, a natural hill that contains mostly cemeteries but also a fortress wall.

There was indeed much more to learn about Pella, just as Bob Smith anticipated. It is one of the longest-lived settlements in the entire southern Levant.

032

The first settlers arrived at Pella in the early Neolithic period, around 7500 B.C., probably attracted by the copious pure waters of the perennial spring that bubbles forth from the base of the settlement mound. Rich agricultural flatlands surround the site on the north and west, and the hills to the south and east are eminently suitable for olive trees and grapes. Located at the natural crossroads of north-south and east-west trade routes, Pella was also ideally situated commercially, a fact confirmed by its more than 8,000-year history of occupation, Jordan’s longest. So if you take on a dig site like Pella, you have to be interested in everything from the content of Neolithic pits to Ottoman rubbish dumps.

Bob Smith’s first season in March–May 1967 was brought to an abrupt halt by the Arab-Israeli “Six-Day War” of June 1967. By 1979 the costs of running a major expedition had increased to such an extent that Bob and my mentor Basil Hennessy of Sydney University in Australia agreed to dig the site together, sharing a dig-house and equipment costs, while running separate excavation seasons: The Aussies dug in January–February, and the Americans in March–May. The Americans completed their field program in 1985; thereafter the Aussies continued alone. I came to direct excavations after Basil retired in 1990 and have been there ever since.

People have been interested in the connection between Pella and the early church ever since Pella was rediscovered for Western scholarship in 1852 by Edward Robinson, an American explorer, theologian and Biblical geographer.a Thereafter, everyone who came to Pella carried a copy of Eusebius with them: Where were the Christians who fled to Pella?

033 034 035

The first systematic exploration of Pella was undertaken by Gottlieb Schumacher in 1887, on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. He quickly identified three major church complexes, ruined but visible below the modern surface, one west of the mound, another east of the mound and a third in the area later to be known as the Civic Complex at the base of the mound.

Schumacher also identified a network of caves and tunnels west of the site, apparently deliberately crafted to hide entrances and restrict access. Given their location and odd arrangement, Schumacher thought these might well be caves used by the early Christians. We will return to these caves later.

In 1924, William Foxwell Albright, then director of the American School in Jerusalem, visited the site. On his surface survey he found pottery sherds confirming Pella’s long history of occupation. It was “Pehel” in the Middle Kingdom Egyptian Execration Texts, and it was “Pihil” of New Kingdom Egypt, mentioned in the 14th century B.C. Amarna letters.

Beyond these important text-based observations, the next major advance in knowledge came with the detailed topographical survey of the site by John Richmond for the British Mandate in 1933. Richmond emphasized the possible connection between Schumacher’s caves with the early Christians who supposedly fled to Pella. In fairness to Richmond, he also noted that these caves were largely naturally formed. And he also documented the careful planning of the site’s major church monuments.

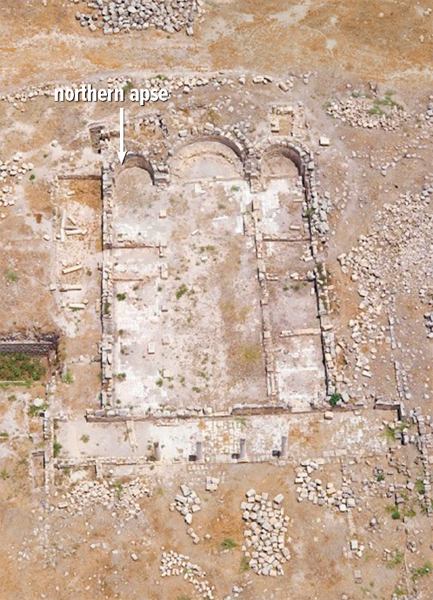

In his 1967 excavation, Bob Smith concentrated on the most accessible of the church complexes. This lay west of the main mound, and, as noted earlier, was thereafter called the West Church (Wooster Area I); surface debris was soon removed and a splendid late Byzantine triapsidal church with associated outbuildings was exposed.

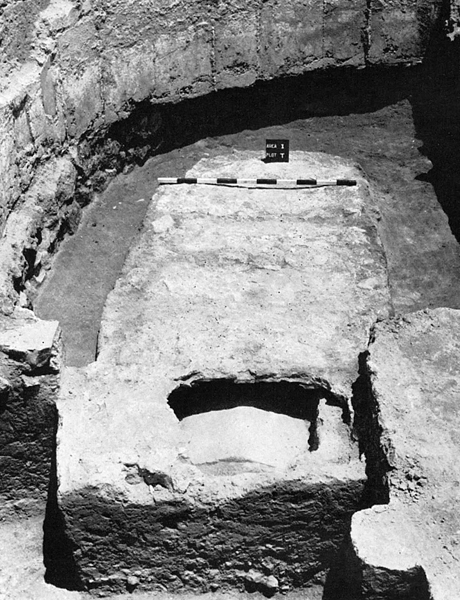

Below the northern apse of the church, Bob’s team discovered a stone-lined grave containing an elaborately decorated limestone sarcophagus. Burials are often found 036 under Byzantine church apses. But a burial below the north apse in these triapsidal churches was special. The north apse was the martyr’s chapel, so a burial under the north apse was likely to be a martyr.

Another unusual thing about this grave: It was not oriented on the line of the church, but at an angle to it; the apse was positioned to cover the entire grave area with minimal disturbance. This suggests that the later Byzantine church had been carefully positioned over the tomb of someone of importance to later church authorities. The frustrating thing was that the tomb had been cleared of all its contents when the church had been constructed on top of it. All but one, that is—the delicately engraved limestone sarcophagus.

A startling thing about this sarcophagus: It was of the type dating from about 80–150 A.D. Bob emphasized two things: the very thin walls of the sarcophagus, carefully pared back to a thin shell, and the fine relief tendril-carved decoration on the sarcophagus exterior. Had Bob found the tomb of a venerated early church father, perhaps one who had fled from Jerusalem in 70 A.D. and later died in Pella?

Anthropological analysis of the badly preserved skeletal remains revealed them to be of a strikingly tall, heavily built man of a goodly age. Unfortunately, the carbon dating (carbon-14) of the bones returned a date in the sixth century A.D., around the time the Byzantine church had been constructed. Some doubt has been cast on the reliability of the radiocarbon dating of the skeleton, however, by the fact that the bones had been severely decayed by a strongly acidic solution (see sidebar). Where this came from remains a mystery. Here was at least a thread to hang the possibility of a flight to Pella by early Christians. Another possibility: The sarcophagus of a worthy who fled to Pella in 70 A.D. was later used for a sixth-century church leader.

When the joint Australian-American team returned to the site in the late 1970s, we concentrated on the main mound, the Aussies in the eastern part and the Yankees in the western part.

One of the first things we both noted was that there seemed to be very little material surviving from the time of the early Christians, the first century A.D. To some extent, this was probably a consequence of the way people built their houses and public buildings then. The larger the building, the more likely you are to level off everything that came before when laying out a new structure. If the building in question was of any great size, it would 037 have required the digging of deep foundation trenches for load-bearing walls. Taken together, these circumstances result in the destruction of earlier horizons of settlement. It’s a commonplace of archaeology that all great civilizations invariably destroy the evidence of their origins, by literally digging it away. At Pella, the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries A.D. (the Byzantine period) were times of ever-increasing prosperity, and ever-more-intensive building activity. The result is that very little has survived on the mound from the first and second centuries A.D.

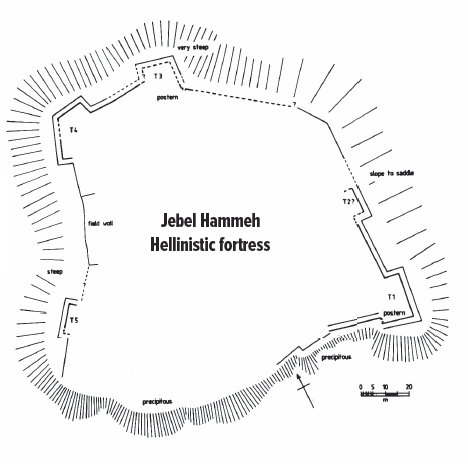

South of the main mound of Pella, across the deeply carved Wadi Jirm, is the steep, largely natural hill called Tell el-Husn (Arabic for fortress). On the northern slopes of the hillside of Tell el-Husn is a stretch of beautifully constructed limestone fortification wall. This wall probably once ringed the summit of the hill. Basil Hennessy’s codirector and Hellenistic pottery ceramicist, Tony McNicoll, dated some of the material linked to the wall to the Herodian and early Roman Imperial age. Several coins support this dating.

According to the first-century historian Josephus, Pella was destroyed around 82 B.C. by the Hasmonean Jewish king Alexander Jannaeus, who then ruled the area. Pella changed rulers again in 63 B.C. when the Roman general Pompey crushed the Hasmonean kingdom and freed all the Greek colonial settlements in and adjacent to the Jordan Valley, including Pella. Perhaps this fortress wall was somehow related to these events. In any case, Pompey formed the freed cities into a league called the Decapolis and attached them to an enlarged Roman province of Syria.

Archaeological evidence confirms the Hasmonean destruction that Josephus describes; wherever we dug across the site, thick destruction layers sealed the shattered buildings of Late Hellenistic Pella. On the main mound, there is virtually no trace of any significant occupation between the Hellenistic destruction by Alexander Jannaeus (c. 82 B.C.) and the late third century A.D. If one considers only the evidence from the main mound, one might argue that the early Christians fled to a near-deserted site. However, there may have been some settled presence other than on the main mound. Perhaps on Tell el-Husn.

As already noted, traces of a near-impregnable Husn fortress have survived. We can assume Pella’s citizens continued to occupy the Husn summit in the years after the Hasmonean sack by Alexander Jannaeus. A measure of prosperity seems to have returned to Pella beginning after Pompey’s conquest of the Hasmonean state and especially noticeable after the Roman suppression of the Jewish revolt. It was in this period (c. 80–160 A.D.) that the aforementioned Civic Complex was built near the base of the main mound. It remains the most visually impressive part of the site with a beautiful small theater, shops, paved open areas, a nymphaeum (fountain), a bath-house and, less certainly, a temple. A few tombs at the site can also be attributed to this period. Finally, and most tellingly, the first Roman-period civic coinage issued by the city of Pella dates from the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (c. 82 A.D.). Issuing coinage is a 038 039 clear reflection of economic prosperity.

But what was Pella like in the previous period when the Christians supposedly fled to the city? There is almost no evidence of any form of occupation on the main mound at this time. And the Husn summit fortress seems to have been sparsely occupied then, with but few remains of domestic housing immediately inside the fortress wall. The few scraps of earlier structures at the Civic Complex at the foot of the main mound are neither extensive nor impressive. So, if there is nothing of note on the main mound, and little in the Civic Complex or on Tell el-Husn, where else can we look for an early Christian presence around 70 A.D.?

This brings us back to “Schumacher’s Caves,” the caves that Gottlieb Schumacher explored at the end of the 19th century, which he thought might have been occupied by the Christians who supposedly fled to Pella in 70 A.D.

These caves were cut into the sharply rising north face of the Wadi Jirm some 1,600 feet southwest of the main mound, and nearly a mile from the Civic Complex at the head of the Wadi Jirm.

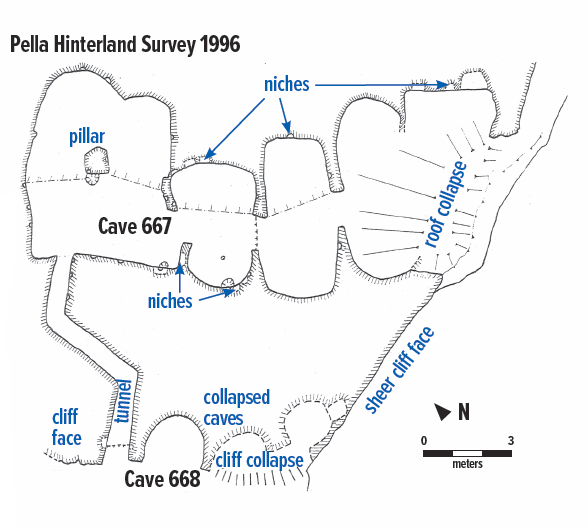

In 1996 my colleague Pamela Watson (then assistant director of the British School) carried out a detailed survey of the Schumacher Cave system as part of the Pella Hinterland Survey (1994–1996). What Pam found was both more and less than she was expecting.

She found two completely separate complexes of underground tunnels, one above the other. The lower complex was fashioned from a combination of canalized natural rock fissures and narrow hewn passages that snake deep within the northern rock face of the Wadi Jirm. Rather than being designed to move people, however, this complex of narrow passageways was designed to bring water from a nearby spring to a series of Roman industrial workshops (including a large pottery kiln complex) set along the northern edge of the wadi. These tunnels obviously had nothing to do with refuge caves.

About 10 feet above this tunnel system, however, Pam’s team found a second series of rock cavities. These caves, apparently unknown to Schumacher (or to his successor Richmond), were partly natural, and partly hewn, and consisted of a series of large, roughly rounded chambers between 10 by 10 feet and 15 by 15 feet, connected together by narrow passageways. Pam did not complete the excavation of the cave complexes but merely explored those that she could most easily penetrate and survey. They were full of bat guano, and there were serious health issues with prolonged exposure to the cave dust. However, in one cave complex (PHS 667) there were five large chambers with short connecting passageways; in complex PHS 668, there were traces of four smaller chambers with interconnections. In all, 12 chambers were documented in Pam’s work.

As strings of connected rooms, these complexes penetrated deep under the rock escarpment, forming a series of hewn and columned rooms, well provisioned with lamp niches and 070 sleeping benches. Airflow and light were ensured by wide porch-like galleries that opened onto the sheer north face of the wadi, completely inaccessible from the wadi bottom some 125 feet below.

Entranceways into these caves were small, concealed and easily defended. They seemed unrelated to any nearby roads or other surface features, suggesting that their construction and use was unrelated to the settled area located some 1,600 feet away.

Unfortunately there was nothing in this cave system that could date it. The caves had been often reused, with each succeeding occupant clearing away any previous debris.

So, in the absence of any carved inscriptions or occupational deposits, the scant dating evidence of these cave systems must remain tantalizingly circumstantial. However, they are the best candidates for an archaeological echo of the early Christian community at Pella.

While the caves provide a bare circumstantial context for an early Christian presence at Pella, the question remains: Why Pella? Cautious speculation suggests that there may have been some local connection between the Galilean leaders of the early Christian community and prominent citizens of Pella. Pella is only 20 miles south of the Sea of Galilee. The Gospels and Acts make it clear that the northern Jordan Valley region was familiar territory for the predominantly Galilean early church leaders. Some scholars have suggested that at least some of John the Baptist’s earlier missionary work may have taken place in the northern Jordan Valley, and not just in the southern Jordan Valley traditionally associated with his activities.2 More practically, three of the best crossing points in the northern Jordan Valley fall within the territory of Pella. With Galilee itself already devastated and occupied by the Romans after the start of the revolt in 66 A.D., Pella might have seemed the safest short-term bet in a very difficult neighborhood.

Finally, a few bits of evidence seem to imply an abiding early Christian presence at Pella. The Christian apologist Aristo (early to mid-second century A.D.) came 071 from Pella, implying a significant Christian presence in the second century A.D., if not earlier. Later Christian historians like Eusebius make it clear that Pella was considered a wellspring of early Jewish-Christian Ebionite thought, which was later condemned as a heresy by Byzantine authorities. If the early Christians fled from Jerusalem to Pella, they may have been the beginning of a major Christian presence at the site.

Did the early Christians flee to Pella? Archaeological evidence of any sort from the first two centuries A.D. is very sparse at Pella. But historical probabilities, geographical realities and the few traces of physical evidence we have recovered during more than 30 years of excavation and survey would all seem to point in the same direction. No one piece of evidence viewed in isolation carries any great weight, but viewed together they form a more coherent whole, suggesting a flight to Pella was possible. More we cannot say.

In 6 A.D., approximately 35 years after Jesus’ crucifixion, the Jews revolted against their Roman rulers, a revolt that ended in 70 A.D. with the burning of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple. On the eve of its destruction, the followers of Jesus, later to be known as Christians, fled from Jerusalem to Pella on the other side of the Jordan River, according to the fourth-century church historian Eusebius of Caesarea: “When the people of the church in Jerusalem were instructed by an oracular revelation delivered to worthy men there to move away from the city and to […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See “Edward Robinson (1794–1863), Biblical Geographer,” sidebar to J. Maxwell Miller, “Biblical Maps,” Bible Review 03:04.

Endnotes

Ecclesiastical History 3.5.3. To the same effect: Epiphanius, the late-fourth century Bishop of Salamis in Adversus Haereses. Panarion 29:7:7–8.