036

When BAR’s editors invited me to prepare a list of significant finds for the 20th anniversary issue, I thought the task would be easy. I had already been developing the forthcoming BAS Slide Set on the Hebrew Bible and archaeology, so I figured I could easily cull 10 slides from these. But as I began to work, I realized that reducing the number from 140 to 10 would be difficult, especially when the chronological horzon was extended to include material later than the time of the Hebrew Bible.

Necessarily, this list is arbitrary and subjective. I selected ten discoveries that give a geographical overview of the lands of the Bible—illustrating how exploding knowledge of ancient cultures has enhanced our understanding of the contexts in which Biblical traditions emerged—and that make arresting and informative pictures.

The most significant discoveries are often texts. But texts seldom provide striking photographs, so I have chosen one—Tablet XI of the Gilgamesh epic—to stand for all the fascinating texts from Mari, Ugarit, Amarna, Qumran and Nag Hammadi, and many other tablets, inscriptions and manuscripts that transmit to us the words of ancient peoples. These silent witnesses have transformed our understanding of the Bible over the last century and a half.

I’ve left out important sites such as Jericho, because neither the mound itself nor its stratigraphic sequences are especially photogenic.

As for Jerusalem, where there’s an embarrassment of riches, I have chosen the exquisitely detailed sixth-century depiction of Jerusalem on the mosaic map from Madaba (in modern Jordan) to stand for all the excavations there since Biblical archaeology began.

This then is my list, arranged in chronological order. Remember that each, in one way or another, stands for many more. You may want to make your own list—perhaps we can update this selection for the 25th anniversary!

038

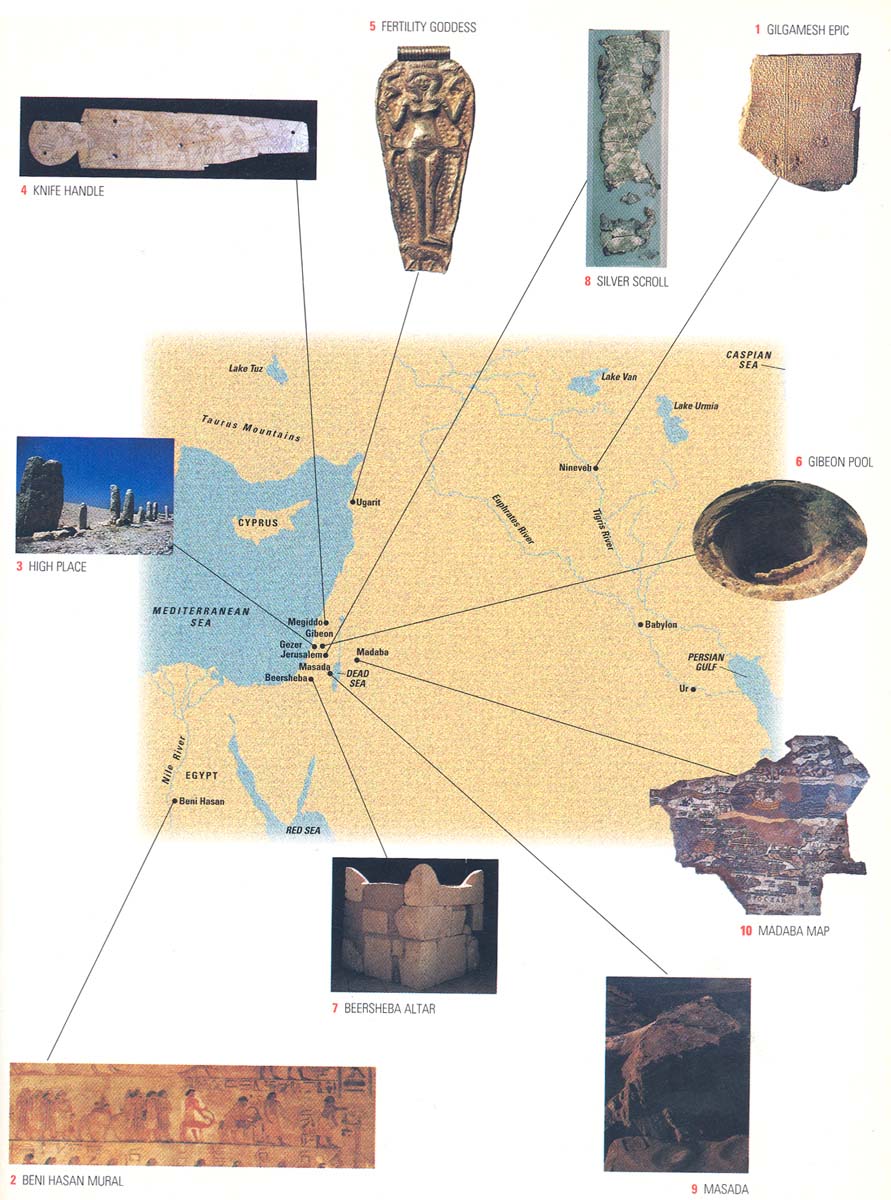

1. Gilgamesh Epic, Tablet XI

7th century B.C.E.

Clay tablet with cuneiform script

Digging in northern Mesopotamia, with techniques too primitive to be called archaeology, the British explorer Austen Henry Layard uncovered tons of monumental sculptures and tens of thousands of inscribed clay tablets, many of which Layard shipped back to London. Among these finds are the famous Black Obelisk of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.E.)a and the library of King Assurbanipal (668–627 B.C.E.), which Layard discovered at Nineveh. After he returned to England in 1851 to pursue a diplomatic career, his work was carried on by Hormuzd Rassam, one of his assistants, who continued to uncover tablets and ship them to London.

After the rapid decipherment of Akkadian (the Semitic language of Mesopotamia, whose two principal dialects are Babylonian and Assyrian), scholars at the British Museum began to catalogue and translate the clay tablets. In 1872, George Smith, an assistant in the museum’s Assyrian Department, discovered on one of the tablets a story about a flood, written down in the seventh century B.C.E., that was strikingly similar to the Biblical story of Noah in Genesis 6–9:

When the seventh day arrived,

I put out and released a dove.

The dove went; it came back,

For no perching place was visible to it, and it turned round.I put out and released a swallow.

The swallow went; it came back,

For no perching place was visible to it, and it turned round.I put out and released a raven.

The raven went, and saw the waters receding.

And it ate, preened, lifted its tail, and did not turn round.b

Smith had happened upon Tablet XI of the Gilgamesh epic, one of the most popular literary works in the ancient Near East. He announced his discovery at a meeting in London of the recently founded Society of Biblical Archaeology on December 3, 1872, where his paper created a sensation. Because the tablet was broken, some of the flood narrative was missing, and Smith went to Nineveh to find the rest; on May 14, 1873, after only five days at the huge, largely untouched site, he succeeded in finding another tablet with the missing lines to the flood story.

The initial reaction was that the Biblical flood story was confirmed as historical—for here was another account of the same event. But subsequent discoveries and analysis demonstrated that Mesopotamian versions of the flood were significantly older than the Biblical accounts, suggesting that the story of Noah and the flood was, in part, a borrowed tale. Moreover, Biblical writers had access to the Gilgamesh epic, as the discovery in 1956 of another part at Megiddo in Israel dramatically proved.c

Gilgamesh’s flood story is one of many texts that parallel and supplement Biblical traditions, strengthening our grasp of the cultural contexts in which the Bible was written, and often forcing us to reconsider traditional views of it.

039

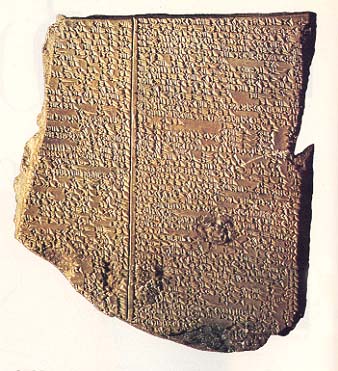

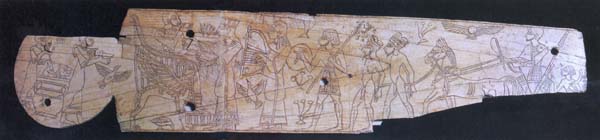

2. Beni Hasan Mural

19th century B.C.E.

8 feet by 1 1/2 feet

About 150 miles south of Cairo on the east bank of the Nile, at a village called Beni Hasan, stands a large necropolis cut into the rock cliffs. In one of the tombs, dating to the early 19th century B.C.E., is a large painting (below) 8 feet long by 1.5 feet high, showing eight men, four women and three children in a procession led by two Egyptian officials. The first official, a scribe, holds a tablet that supplements the hieroglyphic text at the top right of the scene, stating that 37 Asiatics are coming to trade in eye-makeup, which they apparently want to import. Their leader, Abishai, is “the chief of a foreign land.” The Asiatics are equipped with weapons, something that seems to be a musical instrument and a bellows. They are accompanied by donkeys, an ibex and a gazelle; the men are bearded, and all the adults wear garments with elaborate designs.

Although the mural has been frequently used to illustrate the lifestyles of the Israelites’ ancestors—as described in Genesis—many details of this scene remain unclear. Does it depict a caravan of traders, or Asiatics coming to negotiate a mining agreement (suggested by the bellows)? Where are they from—Moab, Sinai or somewhere else? What are they doing over 100 miles south of the Delta, where Egyptian and Asiatic contacts were centered? They certainly are not famished refugees seeking safe harbor in Egypt, like Jacob and his extended family in Genesis. And while it is tempting to link the Asiatics’ clothing to Joseph’s “coat of many colors” (Genesis 37:3; see also 2 Samuel 13:18), the precise meaning of the Hebrew phrase is unknown.

Still, these Asiatics are a vivid portrayal of what some groups traveling from the Levant looked like to the Egyptians, and can serve as a generic illustration of the ancestral traditions in Genesis.

The presence of Asiatics in Egypt increased during the Hyksos period (17th and 16th centuries B.C.E.), the probable time of the migration of Jacob’s family. These contacts have been well documented by archaeological work in the Nile delta, especially recent excavations at Tell el-Maskhuta and Tell ed-Dab‘a.d

Economic and political contacts with Egypt continued throughout the Biblical periods, as archaeological finds attest.e The Joseph story in Genesis, Solomon’s marriage to Pharaoh’s daughter (1 Kings 9:16), and the campaigns of the pharaohs Shishak (1 Kings 14:25–26) and Neco (2 Kings 23:29–35) into Israel are just a few examples of such interaction. And though ancient Israel was more closely connected to the culture of the Canaanites, indirect Egyptian influence is evident in the iconography of Solomon’s palace and Temple, in the love poetry of the Song of Songs, and in the adaptation of an Egyptian saying in Proverbs 22:17–24:22.

After the Exodus, Egypt continued to play an important if subsidiary role in Israel’s history, and the discoveries of Egyptologists continue to shed light on the Biblical world.

040

3. Gezer High Place

1600 B.C.E.

6 to 11 feet in height

This open-air monumental configuration was discovered by the Irish archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister during his first season of work at Tel Gezer in 1902. (For Biblical references to Gezer, see Joshua 10:33; Judges 1:29; 1 Kings 9:15–17; 1 Chronicles 4:16.) It consists of a row of ten stones ranging from about 5 feet to 11 feet in height; the stones are oriented north-south and extend nearly 55 feet from the first to the tenth. To the west of the fifth and sixth stones is a large rectangular basin, made from a block of stone, with a rectangular depression cut into its top. The stones and basin rest in a large plaza that was once plastered and demarcated by a low stone wall. Beneath the installation Macalister found a two-chambered cave containing an infant’s skeleton.

Macalister wrongly concluded that the high place was constructed in the second half of the third millennium B.C.E., with the pillars and other features added later and the final touches made in about the 14th century B.C.E. Macalister believed—again, probably wrongly—that an elaborate series of ceremonies, including child sacrifice, took place there: Oracles were given from caves as at Delphi in Greece; priests perched atop the largest pillar; and people came to kiss the stones.

Most of Macalister’s conclusions have since been abandoned, although his designation of the Gezer complex as a “high place” (a term whose precise meaning still eludes Biblical scholars) has stuck. William Dever’s careful stratigraphic excavation of the high place, in 1968, established that the entire complex dated to the end of the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1600 B.C.E.), and remained in use perhaps into the Late Bronze Age.

The most convincing explanation is that the installation memorialized the making of a covenant, in which each participating group erected a standing stone as a symbolic “witness” to its commitment to a coalition or a suzerain. This would account for the different origins and treatments of the stones. The use of stones as witnesses to a covenant is also mentioned in Genesis 31:43–54, where Jacob sets a stone on a pillar to act as witness to his pact with Laban, and in Joshua 24:25–27, where Joshua sets up a stone to witness the people’s pact with God.f

The purpose of the large basin, however, remains unclear. Some have speculated that it functioned as a socket for a stone or wood object, a laver for ablutions or an altar.

In the ancient world, politics and religion were intertwined. Despite the tendency of archaeologists to attribute a religious function to any unknown feature, a religious interpretation seems most plausible here. Biblical terminology and practices have unquestionably helped shape our understanding of the Gezer high place.g

041

4. Knife Handle

13th or 12th century B.C.E.

Ivory, 10 inches long

The University of Chicago Expedition at Megiddo (1925–1939) was the most extensive archaeological project in Palestine up to that time. Among its many finds was a collection of nearly 400 ivories, discovered in 1937 in a cellar attached to a palace dating to the end of the Late Bronze Age (12th century B.C.E.). The hoard included combs with carved handles, a cosmetic bowl shaped like a duck and another shaped like a nude woman, small caskets and game boards, illustrating the sophistication and eclectic nature of Canaanite art of the Late Bronze Age: Cypriot, Mycenean, Hittite, Canaanite and Egyptian motifs and styles are represented.

As the collection also included gold, alabaster and jewelry, the rooms were probably a treasury of sorts, where valuable items were kept. Ivory pieces are difficult to date unless they are inscribed.h This collection may have been acquired over several generations. Although one piece in the Megiddo hoard contained the name of Pharaoh Ramesses III (1182–1151 B.C.E.), scholars have dated other pieces considerably earlier.

One of the most intricately carved ivories (below) is a knife handle ten inches long. Most likely, two scenes are represented. In the first, from the right, the king returns triumphantly from battle driving a chariot drawn by a horse that is led by two bound, nude, circumcised captives (occasionally identified as Shosu, a semi-nomadic people thought by some scholars to be the ancestors of the early Israelitesi). The captives are preceded by a warrior carrying a spear and a shield. Behind the king is a warrior, or armor-bearer, with a sickle sword, and over the king’s horse floats a stylized winged sun-disk. The king himself apparently wears a coat of mail on his torso and lower arms.

Immediately to the left of this scene and partially separated from it by three plants, is the second scene, in which the king is sitting on a winged-sphinx throne, drinking from a small bowl. He is being attended by two women; closest to him, the queen presents him a lotus blossom and a towel; behind her is a musician strumming a nine-stringed lyre. Behind the throne are two attendants serving drinks from a large tureen, above which, apparently on a shelf or table, are two rhytons, drinking cups with animal heads, one a lion and the other a gazelle. Three birds are whimsically placed in this scene, one beneath the throne and two in the air before and behind it.

The scenes may present a narrative sequence: The king returns victorious from battle and then celebrates the victory. This ivory probably dates to the late 13th century B.C.E., when Megiddo was under Egyptian control.

The Megiddo ivory portrays the luxury of Canaanite royal courts—not very different from life in Solomon’s court in Jerusalem. The royal throne in the ivory is often cited as a parallel to the throne of Yahweh in the Solomonic Temple (see 1 Kings 6:23–28 and Exodus 25:17–22).j

042

5. Fertility Goddess Pendant

14th or 13th century B.C.E.

Gold, 2 5/8 inches long

Like many significant discoveries, ancient Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra in Syria) was found not by professional archaeologists but by a sharp-eyed local resident. In 1928, a farmer plowing his field accidentally opened a tomb; a year later, French archaeologists led by Claude F.A. Schaeffer began excavations on a nearby mound called Ras Shamra (Cape Fennel), and within a few weeks found the first of thousands of inscribed clay tablets that would reveal much about the history of the western Levant, including the religion and culture of the Canaanites in the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 B.C.E.).

Among the languages on the tablets was a dialect of Northwest Semitic, known as Ugaritic and closely related to Hebrew and Phoenician. This linguistic kinship points to deeper connections among Near Eastern peoples. The ancient inhabitants of the modern countries of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel shared a culture that was continuous in time and space. There were, to be sure, local differences, but what the discoveries from Ugarit and other sites show is that the commonalities, as between Canaanites and Israelites, were pervasive, so that many features of Biblical Israel that were once thought unique now prove to be variations of underlying Canaanite traditions.k

This gold pendant was found in a princess’s tomb in Minet el-Beida, Ugarit’s port city. It resembles the many thousands of nude goddesses in diverse forms and media found throughout the Levant.l The pendant depicts a female figure facing the viewer and standing on a lion. Her hair is in the “Hathor” style (from the conventional depiction of the Egyptian goddess). In each hand she holds an ibex; two snakes crossed behind her waist extend downward on either side. The background is a stylized starry sky.

Inscribed Egyptian examples of the same goddess identify her as Qudshu (“Holiness”). This deity was worshipped under various names (Ashtart, Anat) in different places and at different times. She was the principal goddess of the Canaanites, and probably of the Israelites as well.

One element of popular religion in ancient Israel is the worship of a goddess known in the first millennium as Asherah. As with her manifestations elsewhere, she is the consort or wife of the chief deity—in Israel’s case, Yahweh. She is known not only from archaeological discoveries, such as inscriptions from Kuntillet Ajrud in the northern Sinai, but also from the prophets: Jeremiah (7:18 and 44:17–19) calls her the “queen of heaven,” which may explain the starry background of the pendant. There are traces of the goddess elsewhere in the Bible and the Apocrypha, notably in the figure of Wisdom, who is variously described as Yahweh’s partner in creation (Proverbs 8:15–16; Wisdom of Solomon 8:1), a member of his council (Sirach 24:2), and even his lover (Wisdom of Solomon 8:3; Proverbs 8:30).m

Discoveries such as this pendant remind us that Israel was very much a part of the Levant, rather than a separate entity. As Ezekiel put it, “By origin and birth you are of the land of the Canaanites” (Ezekiel 16:3).

043

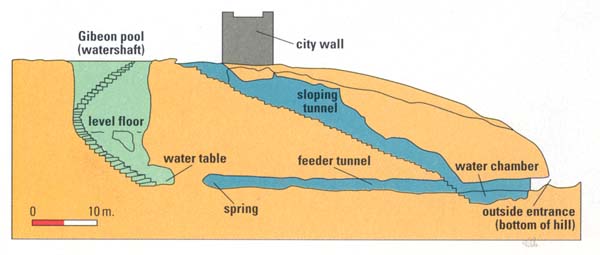

6. Gibeon Pool

11th century B.C.E.

37 feet in diameter, 82 feet deep

In 1833, the American geographer and Bible scholar Edward Robinson recognized that the Palestinian village of el-Jib—located where the Bible suggests ancient Gibeon stood—preserved its name. Though not all scholars agreed, James B. Pritchard’s excavations (1956–1962) settled the matter by finding 31 jar handles inscribed with the Hebrew word gb‘n (Gibeon) in a winery at the site. In the late Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.E.), Gibeon was an important producer and exporter of wines that bore its name on the ancient equivalent of a label.

Among Pritchard’s other discoveries was a complex water system. In the ancient Levant, the lack of rainfall in the summer months required large settlements to make special provisions to procure water. Often there were springs at the bases of the hills on which the ancient cities were built; in other cases, cities arose on sites with relatively high water tables, with the inhabitants sometimes devising elaborate methods to gain access from within the city walls to these sources of water—as was done at Gezer, Hazor, Megiddo and Jerusalem.n

At Gibeon, Pritchard found two separate water systems. The first system, shaded light blue in the section drawing, consists of two connected tunnels. One tunnel slopes down from just inside the city wall to a water chamber outside of the city at the base of the hill on which the city was built. This chamber was filled by a spring located under the hill, almost directly beneath the entrance to the sloping tunnel. Another, feeder tunnel was built by Gibeonite engineers to enhance the flow of water from the spring to the chamber.

The second system (shaded light green in the section drawing, and shown in the top photo) consists of a large, round shaft 37 feet in diameter. This shaft, located near the entrance to the sloping tunnel of the first system, was cut into the limestone bedrock to a depth of over 82 feet. Also cut into the limestone are a staircase and railing, which wind down to a level floor about halfway to the bottom of the shaft. From there, the stairs drop straight down another 45 feet—to the level of the water table.

There is considerable disagreement among scholars about the dating of the Gibeon water systems: Was the shaft built before the sloping tunnel? Were the two phases of the shaft—one leading down to the level floor, and the other dropping to the water table at the bottom of the shaft—a single project? And when were the two systems built?

The Bible may give some answers. References to the “pool of Gibeon” in 2 Samuel 2:13 and Jeremiah 41:12 suggest that the larger circular shaft may have been in use as early as the 11th century B.C.E.

044

7. Beersheba Altar

8th century B.C.E.

Sandstone cube, 63 inches tall, wide and long

In Biblical tradition, Beersheba is the southern limit of ancient Israel (“from Dan to Beersheba”). Beersheba is mentioned in the ancestral narratives of Genesis, where it is associated with Abraham, Hagar, Isaac and Jacob; in King Josiah’s religious reform of the late seventh century B.C.E.; and, in passing, in Amos (5:5 and 8:14). The site of Tell es-Seba‘ appears to preserve the ancient name (Beersheba means “well of the oath” [Genesis 21:31], “well of the seven” [Genesis 21:28–30] or “well of abundance” [Genesis 26:32–33]), and was the focus of eight seasons of extensive excavation by Yohanan Aharoni starting in 1969.o Not all scholars, however, accept this identification of Biblical Beersheba with Tell es-Seba‘ (4 miles east of modern Beer-Sheva), in part because there is no evidence that the site was occupied between the fourth millennium B.C.E. and the 12th century B.C.E.p

Among the most dramatic discoveries at the site were several large, carefully dressed stones found incorporated into the walls and fill under a rampart dating to the late eighth century B.C.E. When gathered together, these stones formed a cubical altar (below) with four tapered projections or “horns” (see, for example, Exodus 29:12; 1 Kings 1:51, 2:28). Though horned altars have been found elsewhere in Israel, this one, when reconstructed, was remarkably large: roughly 63 inches high by 63 inches wide by 63 inches long (though stones found later suggest the length may have been closer to nine feet).

Contrary to Biblical law (Exodus 20:25), the altar was built of hewn stones and had a serpent incised on one of its blocks. Sacrifices had apparently been burnt on the altar, for the top stones were blackened. The Beersheba altar, then, provides rare evidence of religious rituals carried out in a Judahite city other than Jerusalem.

Considerable controversy has arisen over the location of the altar within the city, since its stones were dismantled long ago. Aharoni proposed that a temple, analogous to the one he had found earlier at Arad, once stood at Beersheba and was completely obliterated during King Hezekiah’s religious reform in the late eighth century B.C.E. and by subsequent building. Shortly after Aharoni’s death in 1975, Yigael Yadin proposed an equally hypothetical reconstruction—that the altar was located in a bamah, a raised place where priests burned sacrifices, inside the city gate.q Yadin’s view was attacked by Aharoni’s students and colleagues, in one of the bitterest rivalries in the history of Israeli archaeology. Given the lack of stratigraphic evidence, neither proposal can be proven, but there is a growing consensus that Aharoni’s association of the dismantling of the altar with Hezekiah’s reform is correct. There was later some minor rebuilding of the city prior to its destruction by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E.

The Beersheba altar reminds us how little we know. Although archaeology often sheds light on Biblical traditions, almost every excavation raises more stratigraphic, interpretive and historical questions than it answers.

045

8. Silver Scroll Amulet

7th century B.C.E.

Silver, 1 1/2 inches by 1/2 inch

On an escarpment known as Ketef Hinnom overlooking the Hinnom Valley (Gehenna) opposite Mt. Zion, southwest of the Old City of Jerusalem, Gabriel Barkay excavated seven burial caves from the late seventh century B.C.E., the last days of the Davidic monarchy. Like other ancient cemeteries, this one was located outside the inhabited city because of the association between death and ritual impurity.

In design, these family tombs, cut into the limestone cliff, are typical of the period. Most consist of a single chamber with burial benches on three sides. In one cave, the benches have headrests, and in four caves there are spaces under the benches for burial goods and offerings, as well as for the bones of the deceased once the flesh decomposed. Most of the caves had been plundered or destroyed, but in Cave 4, exposed in 1979, the repository was found undisturbed. It contained the bones of at least 95 people, along with over 250 complete pottery vessels from the late seventh to the fifth centuries B.C.E.—attesting to a continuity of use after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E.—and some from the first century B.C.E. Among other finds in the repository were over 40 arrowheads, incised pieces of bone and ivory, and over 100 pieces of gold and silver jewelry.

The most significant objects in the repository of Cave 4 were two small cylindrical scrolls of pure silver (the smaller scroll, with a drawing, is shown above).r When rolled, these scrolls have a hole running lengthwise through the center, allowing them to be hung around the neck as amulets. The larger one measures 4 inches by 1 inch, and the smaller one only 1.5 by .5 inches, when unrolled: Inside, they are both inscribed with about 18 lines of writing, including the following:

“May Yahweh bless and keep you;

May Yahweh cause his face to shine upon you and grant you peace.”

These familiar words are also found in the “Priestly Blessing” in Numbers 6:24–26, still used today by Jewish parents to bless their children on the Sabbath and in synagogue ritual.

The scrolls from Ketef Hinnom are the earliest inscriptions containing a text also found in the Bible. The text is not necessarily a quotation from the Bible; it is probably a popular blessing that was later incorporated into the Bible in a somewhat expanded form. But the two amulets are evidence of the antiquity of traditions preserved in the Bible; it also provides indirect evidence, as do the Dead Sea Scrolls and other manuscripts from the Second Temple period, of the accuracy of scribes who for centuries copied sacred texts.

It is tempting to speculate on why these amulets were included among burial goods. They may simply have been prized possessions of the deceased; or, as some have suggested, they may have been placed in the tomb as a plea for divine protection of the deceased in the afterlife. In any case, the amulets’ significance is inversely proportionate to their size, for they are our earliest witnesses to the text of the Bible.

046

9. Masada

2nd century B.C.E.

4593 feet in circumference

Excavations at Masada provide us with a précis, as it were, of the history of Roman Palestine from the Maccabees in the second century B.C.E. to the Byzantine period in the sixth century C.E. Led by Yigael Yadin between 1963 and 1965, these excavations give especially important information about the reign of Herod the Great (40–4 B.C.E.) and the First Jewish Revolt (66–73 C.E.).

Isolated in the rugged wilderness along the western shore of the Dead Sea, Masada was identified in 1838 by Edward Robinson and Eli Smith. Yadin excavated there mostly during two winters, the best season for working along the Dead Sea, where summer temperatures are brutally hot. Yadin made use of thousands of volunteers from around the world and from the Israeli army, which set a pattern for subsequent excavations in Israel and, recently, elsewhere in the Middle East as well.

Herod the Great gave the site most of its distinctive features: the casemate (double) wall surrounding the crest of the hill, an elaborate system for diverting and storing runoff from winter rains, a storehouse complex covering about 2,200 square yards, a large bathhouse of Roman design, and a sumptuously decorated villa built on three terraces at the northern tip of the cliff. Masada was one of several citadels Herod built as refuges from his potential enemies; if need arose, he could live in luxury approximating that of his capital in Jerusalem.

During the First Jewish Revolt, Masada was the last stronghold of Jewish rebels fighting against Rome, often called the “Zealots.” Roman camps surrounding the site, and the massive earthen ramp built by the Romans to attack the fortress’s western wall, have been uncovered by excavators. The defenders built one of the earliest known synagogues, and also had a small library containing Biblical and non-Biblical manuscripts, including the best preserved early text of part of the apocryphal Hebrew Book of Ben Sirach. Among other intriguing finds at the site were eleven ostraca (pieces of pottery) inscribed with names—including the name of “Ben Yair,” perhaps Eleazar Ben Yair, the leader of the defenders. According to Josephus, Ben Yair and ten others killed their compatriots, their families and themselves once defeat was inevitable, preferring death to capture by the Romans. Josephus relates that the ten were chosen by lot, and Yadin tentatively proposed that this ostracon was in fact one of the lots.s

Masada has become a symbol of Israeli independence; it also illustrates the interplay of archaeology and history with nationalism and politics that has long characterized the Middle East.

047

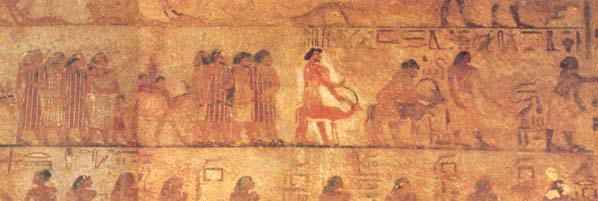

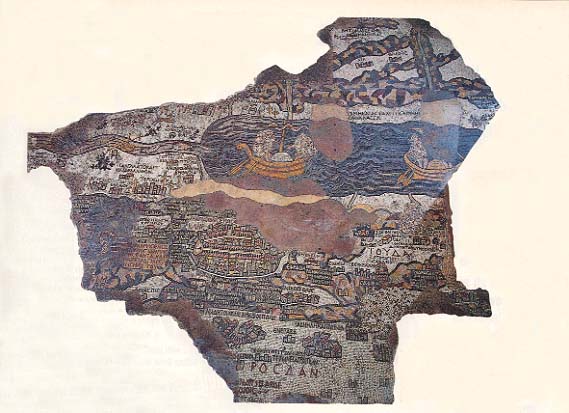

10. Mosaic Map

6th century C.E.

Stone and glass tiles, 297 square feet

The oldest surviving map of the Holy Land, this mosaic is preserved on the floor of a sixth-century church at Madaba in Jordan, about 18 miles south of Amman. The map was discovered in December 1884 during the construction of a modern church in the village, and was restored in 1965 by Herbert Donner.t

What survives of the map covers about 33 square yards of the nave of the ancient church. It is estimated, however, that originally it was more than three times as large. Composed of more than two million stone cubes (tesserae) and pieces of glass in a variety of colors, the map depicts the Holy Land as known by pilgrims and scholars in late antiquity—from Tyre in Lebanon to the Nile Delta, and from the Mediterranean to the Jordanian desert.

Numerous sites are identified in Greek on the map. Just to the north of Jerusalem is a text taken from Deuteronomy 33:12: “Benjamin, God shields him and dwells in between his mountains.” The map’s orientation is to the east, rather than to the north as in most modern cartography: This was ancient Semitic practice (the Hebrew word for east, qedem, literally means “what is in front”). Early Christian churches were also oriented to the east. Empty spaces on the map are filled with flora and fauna, often designed in charming detail. In the Jordan River, fish are swimming; and just east of the river, a lion chases a gazelle.

Jerusalem lies at the center of the map because it was thought to be the center of the world (see Ezekiel 5:5, 38:12). As the focal point of the map, Jerusalem is disproportionately large, measuring about 3 feet by 2 feet. It is depicted as a walled city fortified by towers. At the north (or left) side of the city is the Damascus Gate, just inside of which is a large open plaza with a column in its center seen as if lying on its side; the modern Arabic name for the Damascus Gate, Bab el-‘Amud (“the gate of the pillar”) recalls this feature. Running south (left to right) from the Damascus Gate through the center of the city is the ancient cardo maximus, a colonnaded street that leads to Zion Gate. At the far right in the oval of Jerusalem, just inside Zion Gate, is the “Nea” church with its peaked roof and double door, the “new” church of the mother of God, consecrated by the emperor Justinian in 542—one piece of evidence for the map’s date. At the center of the city, on the west side of the cardo (at the bottom of Jerusalem) is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the traditional site of the death and burial of Jesus. The church appears upside down. It is entered by steps from the cardo; a roof covers the church, and a golden dome (appearing inverted) sits above the tomb itself.

Many of the details of the ancient city’s topography in the Byzantine period as shown in the map were confirmed by the excavations of the late Nahman Avigad in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. Avigad exposed nearly 220 yards of the cardo, as well as the extensive foundations of the Nea church.

When BAR’s editors invited me to prepare a list of significant finds for the 20th anniversary issue, I thought the task would be easy. I had already been developing the forthcoming BAS Slide Set on the Hebrew Bible and archaeology, so I figured I could easily cull 10 slides from these. But as I began to work, I realized that reducing the number from 140 to 10 would be difficult, especially when the chronological horzon was extended to include material later than the time of the Hebrew Bible. Necessarily, this list is arbitrary and subjective. I selected ten discoveries […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Tammi Schneider, “Did King Jehu Kill His Own Family?” BAR 21:01.

See Tikva Frymer-Kensky, “What the Babylonian Flood Stories Can and Cannot Teach Us About the Genesis Flood,” BAR 04:04.

See Frank Yurco, “3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt,” BAR 16:05; and “Can You Name the Panel with the Israelites?” BAR 17:06 with responses from Yurco, (“Yurco’s Response,” BAR 17:06) and Anson F. Rainey (“Rainey’s Challenge,” BAR 17:06).

See Charles R. Krahmalkov, “Exodus Itinerary Confirmed by Egyptian Evidence,” BAR 20:05.

For information on ancient Near Eastern covenants, see Kenneth A. Kitchen, “The Patriarchal Age: Myth or History?” BAR 21:02.

For information on the deterioration of the Gezer high place, see two articles in BAR: “The Sad Case of Tell Gezer,” BAR 09:04, and “Memorandum: Re Restoring Gezer,” BAR 20:03.

See Richard D. Barnett, Ancient Ivories in the Middle East, Qedem 14 (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University, 1982); and “Ancient Ivory: The Story of Wealth, Decadence and Beauty,” BAR 11:05.

See “Can You Name the Panel With the Israelites?” BAR 17:06; and responses by Anson F. Rainey (“Rainey’s Challenge,” BAR 17:06) and Frank J. Yurco “Yurco’s Response,” BAR 17:06).

See two articles in BAR 20:01: Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20:01 and Graham I. Davies, “King Solomon’s Stables—Still at Megiddo?” BAR 20:01.

See Michael D. Coogan, “Canaanites: Who Were They and Where Did They Live?” Bible Review, June 1993.

See Oded Borowski, “Not All That Glitters Is Gold—But Sometimes It Is,” BAR 07:06.

See the following articles in BAR: J. Glen Taylor, “Was Yahweh Worshiped as the Sun?” BAR 20:03; Ruth Hestrin, “Understanding Asherah—Exploring Semitic Iconography,” BAR 17:05; André Lemaire, “Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06; and Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort?” BAR 04:03.

See Dan Cole, “How Water Tunnels Worked,” BAR 06:02.

See Anson F. Rainey, “Yohanan Aharoni: The Man and His Work,” BAR 02:04.

See Volkmar Fritz, “Where is David’s Ziklag?” BAR 19:03.

See Hershel Shanks, “Yadin Finds a Bama at Beer-Sheva,” BAR 03:01. See also Beth Alpert Nakhai, “What’s a Bamah? How Sacred Space Functioned in Ancient Israel,” BAR 20:03.

See Gabriel Barkay, “The Divine Name Found in Jerusalem,” BAR 09:02; see also Barkay, “The Priestly Benediction on Silver Plaques from Ketef Hinnom in Jerusalem,” in Tel Aviv 19 (1992).

See Ehud Netzer, “The Last Days and Hours at Masada,” BAR 17:06; and Jodi Magness, “Masada—Arms and the Man,” BAR 18:04.