044

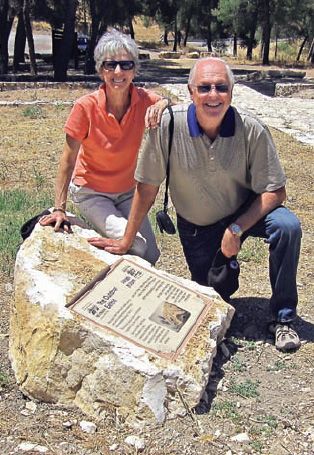

It’s been 28 years since we finished our excavations at Nabratein and we’ve just published our final report, a hefty volume of 472 pages.1 Twenty-eight years may seem like a very long time; but for us, it seems like yesterday. We retain wonderful and vivid memories of our two seasons at Nabratein, the last of four sites that we excavated in Upper Galilee.

The highlight of the excavation of Nabratein was the discovery of a large, beautiful fragment of the pediment of the Holy Ark from the site’s Roman-period synagogue. The excitement of that discovery, which coincided with the appearance of the Indiana Jones movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, thrust the dig and its senior staff into the headlines. The media got it all wrong, though, and came up with some hokey banner headlines such as “Ark of the Covenant Found in Desert of Galilee.” Surprised as we were by the media attention, we went along with most of it, posing for People magazine (the photographer actually moved into our house for a few days), and appearing on “Good Morning America.” We took advantage of these opportunities to tell people about “real” archaeology and how it was not like the archaeology of Raiders, and that mundane potsherds were every bit as important as “lost arks.” We also emphasized that working closely with students and staff from all over the country was especially meaningful; we have maintained our connection with many of these people.

One aspect of the Nabratein experience that we did not share with the media at the time was how strongly ultra-Orthodox Jews in the area opposed our fieldwork. We should explain that the dig was the centerpiece of a Duke University academic program that consisted of field work, study tours to nearby sites in Galilee and the Golan, and lectures and seminars at our base camp in nearby Meiron, an Orthodox moshav (kibbutz). Meiron is located north-northeast of Safed on the eastern edge of the highlands of Upper Galilee in a beautiful, reforested Jewish National Fund park that is also home to 045various burial sites of venerated rabbis, most dating from late medieval to modern times. BAR readers familiar with dig photos will know that in the middle of the hot Israeli summer, most dig participants wear shorts and the women often wear skimpy halters or tank tops. When the ultra-Orthodox realized that we were excavating Nabratein’s ancient synagogue and noted the women who, in their eyes, were immodestly attired, and realized that many of the students and staff were non-Jews, they were horrified. Their mode of protest was to vandalize the site. One evening, after we had left the site at the end of the day’s work, they entered the digging areas, knocked over ancient columns that we had only just reerected, broke down the balks and stole equipment. The next morning we arrived to see that that the site was a mess. It was clear that we could not continue without some protection.

We found our knight in shining armor in the person of Dr. Motti Aviam, then of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel and now professor at Kinneret College. He enlisted volunteers from the nearby Mount Meiron Field School. Fully armed, they slept at the site and fended off the intruders for weeks till our work was finished and we could remove valuable material to our base camp and ultimately to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) headquarters at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem.

Although we were dismayed by this experience, we were not completely surprised. Some years earlier we had encountered similar protests—first while digging tombs (which was legal at that time, in the 1970s) at Khirbet Shema‘. Unfortunately, the religious establishment still inhibits the excavation of Jewish tombs and the examination of human remains, thereby interfering with research that would advance the study of disease. While we were excavating in Meiron, an ultra-Orthodox rabbinic court once decided that the women in our group, when walking to and from the site on the outskirts of the moshav, had to be modestly covered in full-length smocks. We did agree to that, especially since the women would be allowed to wear shorts at the site. However, we did 046not acquiesce to another of their directives, namely, that we forbid students or staff to wear chains or necklaces with crosses. Somehow, we won that battle, with Eric offering a strong and heated rebuttal in his fluent Hebrew.

Along with our vivid memories of digging at Nabratein, we acknowledge that we failed to live up to our resolve to make the results of our field projects available in a timely fashion. The first project, at Khirbet Shema‘, was published just three years after field work was completed; the second one, at Meiron, took four years; and it took somewhat longer, nine years, for the dig report on the third site, Gush Halav, to appear. Not bad. But for Nabratein the time lag has been 28 years, and we are quite embarrassed. Having said that, we also want to suggest that there are some positive aspects to having waited such a long time.

For one thing, we have been able to take advantage of the expertise of a coterie of younger scholars to write the specialty reports. Some of these scholars were probably in diapers when we were excavating Nabratein. Their contributions have enormously enhanced the publication. Another benefit of the long delay is that the presentation of pottery and artifacts takes into account new knowledge and analytical techniques that have emerged in these 28 years. Finally, the perspectives on archaeology that we have gained over the decades that have separated our field work and publication have enabled us, we hope, to produce a volume that is more in tune with current field strategies and interpretive methodologies. It will thus be more useful to a new generation of archaeologists and students than if it had appeared in the 1980s. Our long-overdue publications may actually have some redeeming features as a result of the delay!

It’s been 28 years since we finished our excavations at Nabratein and we’ve just published our final report, a hefty volume of 472 pages.1 Twenty-eight years may seem like a very long time; but for us, it seems like yesterday. We retain wonderful and vivid memories of our two seasons at Nabratein, the last of four sites that we excavated in Upper Galilee. The highlight of the excavation of Nabratein was the discovery of a large, beautiful fragment of the pediment of the Holy Ark from the site’s Roman-period synagogue. The excitement of that discovery, which coincided with the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

1.

Eric M. Meyers and Carol Meyers, Excavations at Ancient Nabratein: Synagogue and Environs, Meiron Excavation Project VI (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009).