To understand how circumstances in the 1870’s led the forger of the Paraiba inscription to undertake such a task is not difficult after reading Frank Moore Cross’ article “Phoenicians in Brazil?” BAR 05:01. Yet many of the same circumstances, so masterfully described in that article, could also lead one to conclude that the inscription is authentic.

In Book 4, Chapter 42, the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 B.C.) reports on a fascinating voyage said to have occurred about 150 years earlier. According to Herodotus’ account, in about 600 B.C. by our calendar, Pharaoh Necho of Egypt chartered some ships for an exploratory voyage. The ships were penteconters, 50-oared galleys suitable for extended coastal explorations. They belonged to the Canaanites, a famous nation of seafarers and merchants, who spoke a language closely related to Hebrew. Greeks and, later, the Romans referred to them as Phoenicians. The galleys set out from Ezion-Geber on the Red Sea to sail around Africa in an effort to find the shortest route to the markets of Europe. According to Herodotus, the 50-oared ships finally made their way to the Mediterranean, arriving in Egypt nearly three years after setting out. The cruise, estimated at over 15,000 miles, was the longest ever made in ancient times. But because penteconters carried a square sail, they did not have to row the entire distance.

This expedition, says Herodotus, was the first to prove that Africa was a continent. Unfortunately the route was too long—Africa was too large—to provide a profitable commercial route from the Red Sea to Europe.

Herodotus’ account is brief and lacks details. He does not even mention the name of the commander of the expedition, a surprising omission in classical literature, leading some to question whether the expedition actually occurred. Herodotus himself doubted at least part of the narrative because, according to the story, the sun’s course was on the right side of the vessel when it rounded the African Horn. Herodotus thought it impossible that the sun’s course could be on the right side rather than the left when rounding Africa.

In the early nineteenth century—before the discovery of the Paraiba inscription—the great German naturalist, Baron Alexander von Humboldt, read Herodotus and concluded that the observation of the sun on the right side was convincing proof that the Canaanites or Phoenicians had in fact traveled far south of the Equator. In the mind of many, this confirmed the authenticity of the circumnavigation reported by Herodotus.

In recent years most classicists have come to accept the voyage as one of the great sailing feats of antiquity. Once the Canaanite galleys reached the Horn of Africa, in present-day Somali, prevailing winds and currents would have pushed the ships all the way round the South African Cape where Atlantic winds and currents continue up the coast to northwest Africa. The galleys would have had hard rowing north along the present-day coast of Morocco, but once at Gibraltar, prevailing westerlies would carry the ships back to Egypt. Nevertheless, later attempts by Greeks and others to circumnavigate Africa from west to east invariably failed because of the winds and currents.

The account by Herodotus does not mention the Benguela Current off West Africa, which sweeps across the Atlantic where it is known as the South Equatorial. This current could easily carry a disabled galley to the Brazilian coast past the Paraiba River, the place where the Canaanite inscription was reported to have been found in 1872.

This historical background in support of a very early Atlantic crossing can be interpreted in two ways—both for and against the authenticity of the Paraiba inscription. Those who are doubters argue that the story of the African circumnavigation was well known, particularly after Baron von Humboldt concluded that it was authentic, and could easily have suggested the creation of the forgery. Educated men knew that the Equatorial Current led to the Brazilian coast. Moreover, as a result of the scholarly interests of the then Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro, who could read Hebrew, there was considerable interest in Semitic inscriptions in Brazil at the time. Since Canaanite inscriptions became a hobby among those who read Hebrew, one can assemble a strong case of circumstantial evidence suggesting that all the components of the Paraiba inscription were available to the forger.

And one can take the same facts and reach the opposite conclusion—that the inscription is genuine because of Herodotus’ report. To think that a galley might have been disabled in a storm, and, losing its way, would be carried to the Brazilian coast with a few survivors, is not unreasonable.

The circumstances surrounding the discovery of the inscription can also be viewed positively and negatively. Those who contend that the Paraiba stone is a fraud use as evidence the statement of the National Museum’s director, Ladislau Neto, who said he could locate neither the plantation nor its owner who wrote the letter announcing the discovery; nor could he find the stone itself. This led the director to think that the whole affair was a hoax. The director, years later, said he concluded that there were only five men in Brazil who were capable of composing such a Canaanite or Phoenician text, and so he corresponded with each of them to check their handwriting. The handwriting of one of the five replies matched that of the letter written by the so-called “plantation owner.” Neto, however, never named him.

Some have challenged Neto’s account as untrue. What if the director lied about his identification of the handwriting, or found it similar but not exactly the same? He was not an acknowledged expert in handwriting. Moreover, the director did not tell the handwriting story for years and some wondered why he delayed so long. It has been said that the inscription was denounced as a fraud by a French scholar at the time it was first found. Perhaps Neto—not himself a formidable scholar—agreed with the Frenchman that it was a fraud just to avoid controversy. Perhaps Neto made up the handwriting story to justify his position.

The historical background of the expedition and the circumstances surrounding the inscription do not provide a final answer to the question of authenticity, and this brings the controversy down to the issue of language studies. Two eminent experts on Semitic languages disagree. Professor Frank Moore Cross of Harvard has advanced many arguments in support of his position that the Brazilian inscription was a fraud (“Phoenicians in Brazil?” BAR 05:01). With compelling arguments, he demonstrates that the inscription is not written in pure unmixed Canaanite, and that the letters represent a range of years and styles impossible to find in Mediterranean lands. According to Cross, the text was composed by someone familiar with nineteenth century Phoenician studies, a forger who was more familiar with Biblical Hebrew than Canaanite.

Professor Gordon, on the other hand, accepts the Hebrew mixture and uses it to strengthen the case in favor of the inscription.

In Riddles in History (1974) Gordon reports finding a secret cryptogram in the Paraiba text. Gordon states that the cryptogram is of a form and type unknown to scholars until very recently, and thus could not have been created by a forger in the 1870’s. Professor Gordon unscrambles the cryptogram to read “We have been saved from Death” and “Trust only in Yaw (= Yahweh, God).” According to Gordon, although the author of the inscription was outwardly a worshipper of Phoenician deities, he was in fact a devout Hebrew who believed only in Yahweh. Professor Gordon points to the Biblical book of Jonah as providing another example of a Yahwistic Hebrew at sea with a pagan crew and passengers. If the writer of the inscription were a Hebrew, this might explain some of the obvious influences from Biblical Hebrew which modern day linguists find so objectionable in the Paraiba inscription.

The Hebrew origins of the author of the inscription might explain some of the linguistic anomalies, but does not explain all of them, so Professor Gordon is still in trouble on the basis of a linguistic analysis. Yet, as long as Professor Gordon’s mysterious cryptogram is unchallenged, many will remain convinced that the inscription’s authenticity is an unresolved question.

In the course of writing a book on pre-Columbian voyages I had to come to grips with this difficult Paraiba cryptogram. One test of Professor Gordon’s cryptographic method is to see whether it has proved authenticity in the cases where he has used it. In addition to the Paraiba cryptogram, Professor Gordon claims to have found through his methods three other authentic cryptograms which he describes at length in Riddles in History. In all three of these other cases, standard and customary linguistic analysis has shown the inscriptions involved to be frauds. Professor Gordon’s cryptographic method is irrelevant.

The Kensington Rune Stone was alleged to have been left by a Scandinavian expedition in western Minnesota in 1362. Professor Gordon was not the first to find an authenticating cryptogram in this inscription. The search for a cryptographic message in the rune stone was begun during World War II by a former U.S. Army cryptographer, Alf Monge, who was looking for very complex, hidden messages on runic medieval inscriptions. He was assisted by Ole Landsverk, a Viking enthusiast without formal training in medieval Scandinavian languages. Then Professor Gordon joined them. All three agree that the Kensington rune stone carries two cryptograms: “Tolik carved me, Harrek made me,” and the date “24 April 1362.” They assert that the presence of this hidden information proves that the inscription is genuine.

Orthodox linguistic analysis, however, has convinced all Scandinavian specialists who have examined and studied the Minnesota rune stone that it is a fraud. Using acrostic techniques, Carl Jensen, an amateur Scandinavian studies’ enthusiast, discovered the names of the Kensington residents who participated in the hoax and the year it was manufactured and found (1898). He also found in the inscription a cryptogram which said “15 Feb. 1898 Maine Blows Up.” If one can find cryptographic support for both modern and medieval origins, the techniques are obviously not perfected.

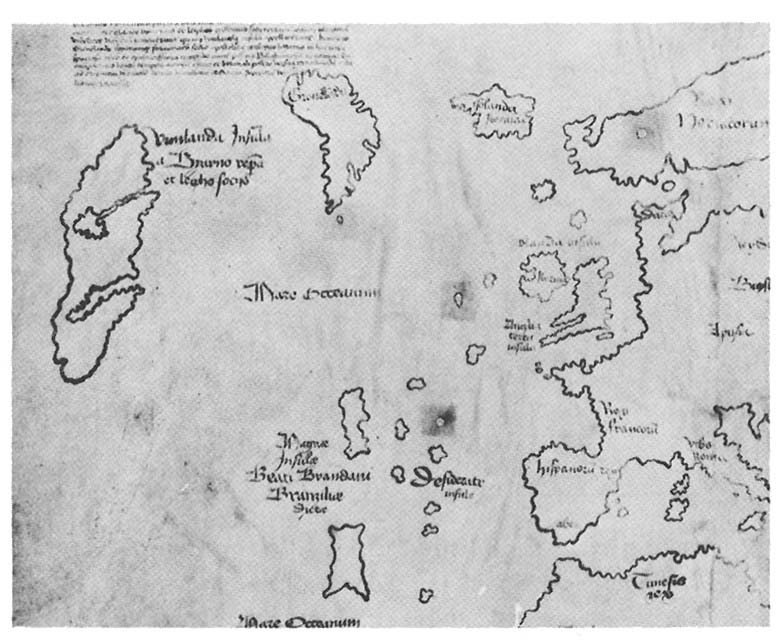

Professor Gordon also found a cryptogram in a caption on the Vinland Map. It reads “Lysander” and is an alleged, if pointless, reference to a Spartan general who used secret messages. The Vinland Map seemed to be the only pre-Columbian map of a portion of the North American coast, and was thought to have been printed in Basel, Switzerland in the 1440’s. Yale University Library purchased the map in the 1960’s for $100,000 for its rare books and manuscripts’ collection.

When Professor Gordon published Riddles in History in 1974 one could argue that if such a cryptogram were genuine and not artificially contrived, it might lend some possible authenticity to the controversial map. However, that same year, the great debate over the authenticity of the Vinland Map was resolved by a symposium of papers given at the Royal Geographical Society in London. The map was proven to be a fraud because the ink contained anatase, a compound unknown until 1917 at the earliest. From many physical, chemical, historical, and geographical lines of evidence, it is certain that the Vinland Map cannot be older than the 1920s and is possibly more recent. Again we find that Professor Gordon’s cryptogram provides a spurious, untrue solution to the question of authenticity.

The Spirit Pond rune stones from Maine were found in 1971. Professor Einar Haugen of Harvard has dismissed them as obvious forgeries because they were concocted by someone familiar with the Kensington rune stone rather than with medieval Old Norse—a fake based upon a fake. Spirit Pond runes spell out a word in modern Swedish, misuse runic numbers to write a date, and contain many amateur errors of the same kind. The map on one of the stones is copied from the local U.S. Geological Survey’s topographic sheet of the Spirit Pond area, rather than from Champlain’s earlier and quite different map—an important proof because the shore line has changed over three centuries. Professor Haugen’s work cites extensive references by runic studies’ specialists who reject the cryptographic approach which Mong and Landsverk advance in connection with the Kensington rune stone and the Spirit Pond rune stones. The runic cryptograms from Spirit Pond discussed by Professor Gordon once again provide an erroneous solution to the problem of authenticity. The stones are fakes and a “secret message” cannot convert them into genuine antiquities.

The Paraiba inscription from Brazil is the fourth unsuccessful attempt by Professor Gordon to transform a fraud. As Professor Cross correctly stresses, the forger must have based his information on available nineteenth-century sources and handbooks. Where these sources erred, so did the forger. The inscription could only have been written in the nineteenth century because of the misuse of letter forms and words which in antiquity dated in usage over a span of at least one thousand years, but never occurred together at a single time or place. By modern standards, the Paraiba inscription cannot possibly be genuine. No cryptogram, no matter what its message, can correct these deficiencies.

As a result of my study, I am convinced that the tablet never existed, and that the hoax was composed entirely on paper, shortly before 1872, by someone with a passably good knowledge of Canaanite for his time. There is no longer a mystery. Professor Cross is correct; Professor Gordon is wrong; uncertainty is no longer possible.

Why has Professor Gordon been wrong four times out of four? When one tries to follow his methodology, one encounters an extremely complex solution formula. He attributes numerical values to individual letters, then chooses and places them in complicated patterns, doubles their values, adds their values together, and then reconverts them into anagrams. In short, he has created a hodgepodge wherein almost anything can be read into any long inscription, whether ancient or modern, genuine or false.

If one is convinced an inscription has a secret message, such methods will produce one, but such contrivances have little to do with the authenticity of the inscription or any intent on the part of its author.

(For further details, see Frank Moore Cross, “Phoenicians in Brazil?” BAR 05:01, and Cyrus H. Gordon, Riddles in History (1974), New York, Crown Press. The three Viking frauds are discussed by Theodore C. Blegen, The Kensington Rune Stone: New Light on an Old Riddle (1968), St. Paul, Minnesota Historical Society. Einar Haugen, “The Rune Stones of Spirit Pond Maine,” Man in the Northeast, Vol. 4 (1972), pp. 62–69. Helen Wallis and others, “The Strange Case of the Vinland Map: a Symposium,” Geographical Journal, Vol. 140 (1974), pp. 183–214. Carl C. Jensen, Again in Kensington Stone (1969), La Cross, Sumac Press. Erik Wahlgren, The Kensington Stone, A Mystery Solved (1958), University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. The African circumnavigation is discussed by John Victor Luce, “Ancient Explorers,” The Quest for America edited by Geoffrey Ashe (1971), pp. 53–95, London, Pall Mall. A broader discussion of pre-Columbian contacts with the New World is by Marshall McKusick, Atlantic Voyages to Prehistoric America (1980), in press, Carbondale, Southern Illinois University.)