A Futile Quest: The Search for Noah’s Ark

001

A recent Readers’ Digest article which suggests that the remains of Noah’s Ark may yet be found atop Mount Ararat in eastern Turkey has rekindled enormous interest in the quest.1

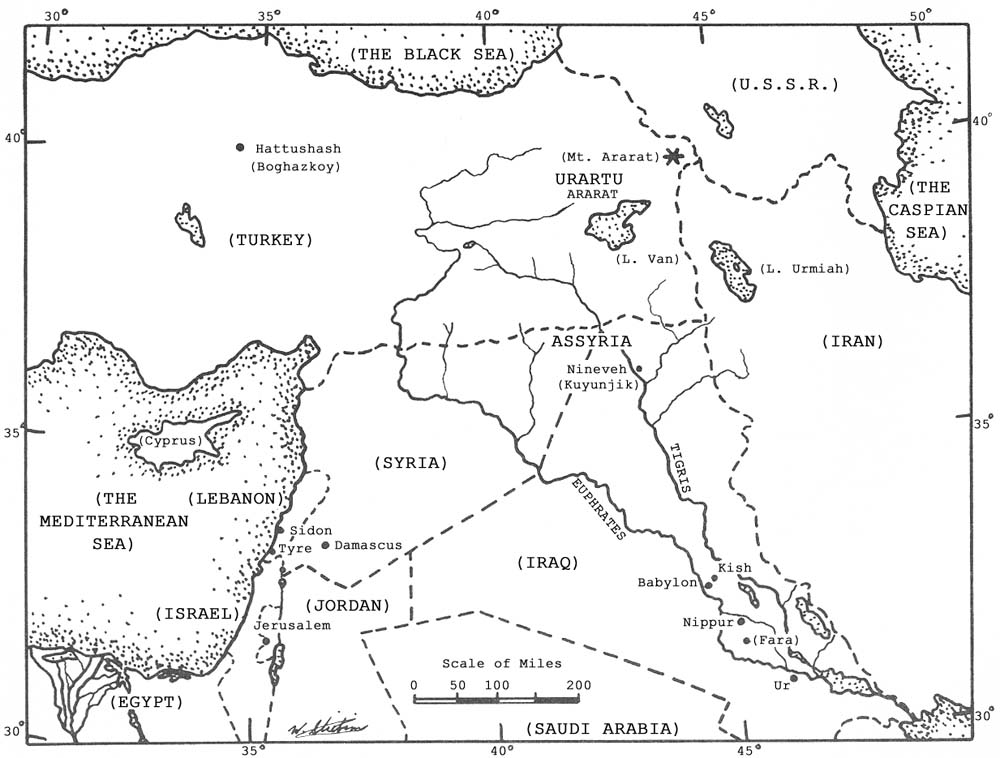

Several individuals and groups have explored Mt. Ararat during the past thirty years, but, as we shall see, no conclusive evidence of the Ark has been found. These efforts have been restricted of late because of internal problems in Turkey, the Greek-Turkish conflict on Cyprus, and the fact that the Turks have become very sensitive about foreign expeditions on Mt. Ararat which overlooks both the Russian and Iranian borders (see map). Nevertheless, many people remain confident that the Ark is still on the slopes of Ararat, waiting to be found.

The story of Noah and the Great Flood is one of the best known tales from the Bible, and has long been a source of contention. Ever since the seventeenth century and the beginnings of modern geology, prehistoric archaeology and evolutionary theory, there have been scholars who have challenged the scientific and historical validity of the early chapters of Genesis—especially the accounts of the creation and the Flood. Others, convinced that the Bible is the literal Word of God, verbally inspired and inerrant, have sought to prove that the Genesis version of man’s early history is correct.

Archaeology has played a somewhat ambivalent role in this debate. In Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries human artifacts and skeletal remains were found associated with the fossils of extinct animals in a number of places. These finds led antiquarians and geologists to abandon the widely accepted chronology which Archbishop Ussher had worked out from Biblical accounts. According to Ussher’s seventeenth century calculations, the creation of the world had taken place in 4004 B.C. and the Great 013Flood had occurred in 2348 B.C. These dates were printed in the margins of some editions of the Bible, and in the minds of many they had assumed an authority and sanctity virtually as great as that of the Biblical text itself. But evidence of the extreme antiquity of man could not be easily reconciled with the very short chronology suggested by the Scriptures. Thus, discoveries in European prehistory contributed to skeptical and scientific attacks on the validity of Genesis.

On the other hand, a number of early archaeological discoveries in the Near East tended to confirm the accuracy of Biblical accounts. Since many assumed the unity of Biblical teaching—either it was all true or it was all false—finds verifying accounts in the books of Kings were often cited as proof of the historicity of the Bible as a whole. Much of the public interest in and financial support for nineteenth and early twentieth century Near Eastern excavations came from individuals and groups intent on verifying Biblical history.

In 1872 George Smith, an assistant in the Assyrian section of the British Museum, made a discovery which raised the debate to a new level. He had been sorting and classifying cuneiform tablets found at Kuyunjik (ancient Nineveh) (see map) by earlier British excavators when suddenly his attention was seized by a line in a broken text which seemed to be part of a myth or 014legend. The sentence read, “On Mount Nisir the ship landed; Mount Nisir held the ship fast, allowing no motion.” Hurriedly Smith glanced down the rest of the column and read:

“When the seventh day arrived,

I sent forth a dove—I released it.

The dove went away, but came back;

Since no resting-place appeared, she returned.

Then I sent forth a swallow—I released it.

The swallow went away, but came back;

Since no resting-place appeared, she returned.

Then I sent forth a raven—I released it.

The raven went away, and seeing that the waters had diminished,

She ate, circled, cawed and did not return.”

Smith knew at once that he had found a Mesopotamian version of the Biblical story of the Deluge.

There was a gap in the text which could not be filled by any of the tablets in the museum. But when Smith reported his discovery in a paper read before the Society of Biblical Archaeology, so great was the public interest that the London Daily Telegraph offered to equip an expedition to Nineveh to search for the missing tablets. In May 1873 Smith arrived at Kuyunjik and began sifting through the debris piled up by previous British expeditions. He found over 300 fragments of tablets which had been unnoticed and discarded by earlier excavators—a sad commentary on the archaeological methodology of the time. Among the texts he recovered was a tablet containing the missing portion of the Mesopotamian flood story.

The flood account found by Smith proved to be part of a seventh century B.C. Assyrian 015copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh.2 But fragmentary copies of the same work dating from the middle of the second millennium B.C. have since been found in the ruins of the Hittite capital at Boghazkoy. Portions of an Old Babylonian version of this epic (c. 1900–1600 B.C.) have also been discovered. However, even without the early fragments of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Assyriologists knew from the language of Smith’s tablets that the story belonged to an era long before the seventh century B.C. Internal linguistic evidence indicates that the Epic of Gilgamesh and the flood story it contains must have been composed near the beginning of the Old Babylonian Period, c. 1900–1800 B.C.—more than five hundred years before the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt.

The Babylonian-Assyrian flood story in the Gilgamesh Epic is so similar to the Hebrew account in Genesis it was clear that the two must be related in some way. A number of scholars argued that the Biblical narrative must have been derived from the earlier Mesopotamian legend. This view became even more persuasive in 1914 when Arno Poebel published a very fragmentary Sumerian account of the Flood. The tablet containing this account had been unearthed in the University of Pennsylvania’s excavations at Nippur between 1889 and 1900. The text was so badly damaged that only limited portions of the story survived: the gods’ decision to send the Flood, the warning to Ziusudra (the Sumerian Noah) to build a large boat, the coming of the Flood, Ziusudra’s sacrifice of thanksgiving after the Flood, and the deification of Ziusudra. Enough remained, however, to indicate that the Sumerian flood story originally contained most elements of the Old Babylonian version found in the Epic of Gilgamesh.3

The Sumerians were non-Semitic inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia who first invented the cuneiform script, used widely in the ancient Near East, and who created the earliest civilization known at present. Their culture was dominant in Mesopotamia from about 3500 to 2400 B.C. Though conquered by the Semitic ruler Sargon of Akkad (c. 2371–2316 B.C.), they continued to play an important role in Mesopotamian affairs until the end of the eighteenth century B.C. Most of the Sumerian literary texts from Nippur, including the flood tablet, were found in the archaeological layer belonging to the time of the Third Dynasty of Ur and the Isin-Larsa Period (c. 2113–1800 B.C.), but the myths the tablets record are almost certainly much older. They reflect social and governmental institutions which had disappeared among the Sumerians long before the beginning of the second millennium B.C. Thus, it is thought that an original Sumerian flood story provided the inspiration for the various Old Babylonian accounts (which in turn served as the models for the Assyrian versions).

The discovery of this Sumerian flood narrative confirmed the great antiquity of the flood tradition in Mesopotamia, and convinced most scholars that the Biblical story of Noah must have had a Mesopotamian origin. But others claimed that the Mesopotamian flood stories proved the historicity of the Biblical Deluge. Supporters of this view argued that the similarities between the Biblical narrative and the account of the Epic of Gilgamesh were not evidence of literary or intellectual dependence, but rather indicated that the two traditions were independent accounts of the same historical event—a great worldwide Flood from which only one human family had been saved. The Genesis account was taken to be an accurate record of what had occurred, while the various Mesopotamian stories were thought to be derived from a tradition which, though originally accurate, had gradually become debased by polytheism and riddled with factual errors.

Then in 1929 more fuel was added to the controversy by Leonard Woolley’s discoveries at Ur in southern Mesopotamia. Workmen digging a pit through the prehistoric Ubaid strata reached what they thought to be virgin soil. But since the level of the “virgin soil” was not as deep as Woolley had expected it to be, he ordered the workmen to continue the excavation. After digging through eight feet of clean, water-laid mud containing no artifacts, the men suddenly encountered Ubaid painted pottery and flint implements once more. Woolley called over two members of his staff and asked for their explanation of the deposits. He recounts that “they did not know what to say. My wife came along and looked and was asked the same question, and she turned away remarking casually, ‘Well, of 016course, it’s the Flood.’ That was the right answer.”4

Woolley thought he had found evidence of the Great Flood which lay behind the Mesopotamian traditions. This flood had not been a universal Deluge, he argued, but it had covered most of Mesopotamia—the “whole world” to the prehistoric people who had lived there. In his opinion, the Biblical story of Noah had been derived from the Mesopotamian flood accounts. Many people cited Woolley’s finds as proof that a worldwide flood had occurred, just as Genesis said. Their conviction was strengthened when over the next few years flood layers were reported from Kish, Fara and Nineveh, three other sites in Mesopotamia (see map).

This archaeological “evidence” of the Flood was widely publicized and found its way into many popular works on Biblical archaeology. However, as Professor John Bright demonstrated in a 1942 article,5 the archaeological discoveries in the Near East do not support Woolley’s interpretation, much less that of some of his popularizers. Mounds in Syria and Palestine (such as Jericho) which exhibit fairly continuous occupation since at least 5000 or 4500 B.C. show no signs of destruction by a Great Flood. Even in Mesopotamia, most sites (including al-’Ubaid near Ur) have produced no evidence of “the Flood.” At those sites where flood deposits have been found, the date of the flood varies widely. The Ur flood layer was in the middle of Ubaid remains (in southern Mesopotamia the Ubaid Period dates from c. 4500 to 3500 B.C.); at Kish, the flood occurred in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900–2400 B.C.); at Fara, the alluvial deposit was between the Jemdet Nasr (or Protoliterate C–D, c. 3100–2900 B.C.) and Early Dynastic layers; and the flood layer at Nineveh separates remains of the Halaf Period (c. 5000–4300 B.C.) from those of the Ubaid (c. 4300–3500 B.C. in northern Mesopotamia). Thus, the flood layers at various Mesopotamian sites are the results of different local floods which were no doubt quite common in that area. They cannot be used as evidence of The Flood of Mesopotamian tradition or of Genesis. Even at Woolley’s Ur, the flood evidence he found did not cover the entire site!

Since World War II many believers in the historicity of the Genesis Flood have centered their hopes on expeditions to Mt. Ararat. Actually, the Bible does not name this mountain as the one on which Noah landed. Genesis 8:4 merely specifies the region where the ark came to rest—“the mountains of Ararat,” or, as the New English Bible translates it, “a mountain in Ararat”. Ararat is the Biblical name for Urartu as this area was known to the Assyrians. This mountainous region, centered around Lake Van, was later called Armenia, but now it is divided between Turkey, the Soviet Union, Iran and Iraq. Armenian tradition, however has long identified Mt. Ararat as the peak on which the ark landed.

Mt. Ararat is located in extreme eastern Turkey close to the borders of the Soviet Union and Iran (see map). It stands in almost solitary splendor, rising to a height of over 16,900 feet above sea level and providing a relief of almost 14,000 feet between its summit and the plains at its base. Since Mt. Ararat is much higher than other mountains in the area, its peak would be the first to emerge above receding waters if the whole region were submerged by a vast Flood. This fact probably explains its traditional designation as the landing place of the ark—although the Biblical account does not suggest that the ark came to rest on the highest mountain of the region.

“Arkeologists” (as the searchers for the ark have come to be called, by themselves as well as by others) provide a number of pieces of “evidence” to support their conviction that Noah’s Ark has survived the centuries atop Mt. Ararat:6

• Ancient historians such as Berossus (a Babylonian priest of the third century B.C. whose account of Mesopotamian history in Greek has survived only in fragmentary quotations by other ancient writers) and Josephus (a Jewish historian of the first century A.D.) mention reports that the ark still existed in their respective eras. Also, medieval travelers such as Marco Polo testify that Armenians of that day claimed that the ark was still on Mt. Ararat.

• Shortly before his death in 1920, an Armenian-born American is supposed to have told friends that in 1856 three atheistic British scientists hired him and his father to guide them up Mt. Ararat to prove that the ark was not there. When the boy 017and his father led the scientists directly to the ark, the scientists threatened them with death if they ever reported the incident. Soon after World War I a British scientist is supposed to have admitted in a deathbed confession that he was one of the three atheists who by death threats had suppressed their guides from divulging the fact of the ark’s existence on Mt. Ararat. This deathbed confession is supposed to have been widely reported in many newspapers of the time. However, no one has ever been able to find copies of these articles or to identify the individuals involved.

• In 1876 Sir James Bryce, a British explorer, found a large piece of hand-tooled wood at the 13,000 foot level of Mt. Ararat.

• In 1883 a group of Turkish commissioners, checking avalanche conditions on the mountain, are said to have found the Ark and entered it. But no one would believe them.

• A Russian aviator supposedly spotted the Ark from the air in 1915 and an expedition was sent to investigate. The Russian soldiers located and explored the ship, but before they could return to St. Petersburg, the Russian Revolution of 1917 occurred. The records of the expedition were lost and the members scattered, but some relatives and friends later reported having heard their story.

• About 1937 a New Zealand archaeologist named Hardwicke Knight was making his way around the mountain near the snow line when he saw what appeared to be heavy timbers projecting from the ice field. Only later did he realize that these may have been part of the Ark.

• During World War II both American and Russian aviators are supposed to have seen the Ark from the air. The Russians even took photographs which are reputed to have appeared in various U.S. papers. The story of one of the American sightings was supposedly reported in a 1943 Tunisian theatre edition of the Army paper Stars and Stripes. However, the articles and photographs cannot now be located.

• In 1953 George Greene, a geologist, took six aerial photographs of an object he believed to be the Ark. He died in 1962 and no trace of his unpublished photographs has been found, though several witnesses claim to have seen them.

• A large piece of hand-worked timber was pulled from a water-filled pocket deep in a crevasse on Ararat by Fernand Navarra in 1955. The partly fossilized wood was dated to about 3000 B.C. by a Spanish laboratory (primarily on the basis of its color and the extent of fossilization), but two independent carbon-14 tests by British and American laboratories have indicated a date around 450–750 A.D.7

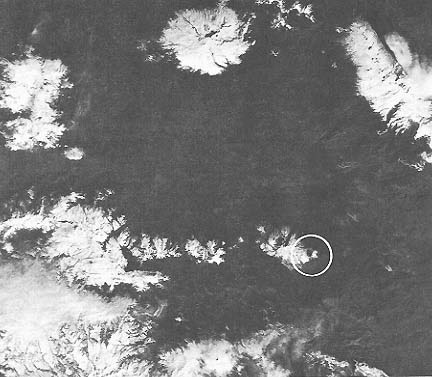

• An orbiting U.S. Earth Resources Technology Satellite has taken photographs of Mt. Ararat which show a number of dark spots in the ice fields. One of these anomalies may represent the remains of Noah’s Ark.

Even non-critical readers will note that most of the above “evidence” rests on hearsay and that it cannot be verified by objective means. Some of it is also inherently improbable. If the exact site of the ark had been known from antiquity down through the Middle Ages as Berossus, Josephus, and Marco Polo state, is it likely that such a revered relic would have been subsequently lost and its precise location forgotten? (It should be noted that despite all the invasions, wars, and social turmoil in Palestine through the ages, the traditional locations of sacred places, once established, have been remembered and revered.) Is it believable that a threat by a pair of foreigners who lived thousands of miles away could have kept a believer silent about his discovery of Noah’s Ark until he was near death more than sixty years later? And why is it that no one can now find copies of the articles and photographs which supposedly documented various modern discoveries of the ark?

Only the wood found by Navarra and the anomalies on the satellite photographs are objective evidence, and they prove nothing. Man has lived around Mt. Ararat for many thousands of years, and for at least the last seventeen centuries the natives of the area have regarded the mountain as the site where Noah’s Ark landed. It would be very unusual if through the ages no buildings, monuments, or other structures using wooden beams had ever been erected on the mountain near the edge of the snow field. Is the beam found by Navarra from the ark or from some other man-made structure? (If the carbon-14 dates are approximately correct, the wood is far too recent to come from the ark.) As for the anomalies in the satellite 018photographs, there are too many of them, and most represent areas too large for the ark. It is much more likely that they represent natural features such as rock outcrops or small glacial lakes than man-made objects such as the ark. In short, the so-called “evidence” for the existence of Noah’s Ark on Mt. Ararat will convince only those who already believe and do not need to be convinced.

But granted that the evidence for the ark’s preservation is not very strong, why are most archaeologists so firmly convinced that the search for its remains is a waste of time and money? What makes them so sure that the Ark isn’t somewhere on the slopes of Mt. Ararat?

First, of course, there are the logical and scientific objections to the Biblical story of the Flood. How could a vessel approximately 450 feet long, 75 feet wide and 45 feet high (Genesis 6:15; the Biblical cubit is about 18 inches long) hold two of every species of animal and bird (and seven pairs of each of the clean species) as well as provisions for a year? Some supporters of the story speculate that there may not have been as many species of animals in Noah’s day as there are today and that the animals may have hibernated, eliminating their need for food.8 However, Genesis 6:21 implies that the animals were to be fed normally during the time they were on the Ark, and, of course, not all species hibernate. Did God miraculously place all of the animals in a state of suspended animation? Those who accept the story as history see no reason why such miraculous intervention should be rejected, for the Flood itself, after all, is not a natural occurrence—it is a mighty act of God breaking into the course of human history. But the fact remains that the Bible does not mention (or even imply) any miracles in connection with the animals on the Ark.

Supporters of the Flood story claim that many geological features of the earth which would normally be explained as the work of millions of years (and thus contradict the relatively recent chronology of Genesis) were actually produced by the turbulent waters of the Flood. According to this theory, the earth’s geography was quite different before the Flood, although it has not changed very much in the ages since. This theory presents its own problems: How did animals from the Ark get to Australia or the Americas after the Ark grounded on Ararat? More miracles not mentioned in the text must be posited.

To accept the Flood account as history one must not only forsake a logical (and even literal) interpretation of the text of Genesis, one must also abandon the principles and results of modern geology and prehistoric archaeology, both of which deny the existence of a universal Deluge during the span of man’s history on earth.

A second major reason why archaeologists and Biblical scholars reject the quest for Noah’s Ark lies in the Biblical text itself. Careful analysis of Genesis has shown that there is not one Biblical flood story, but two. These two different accounts have been skillfully woven together to produce the composite story of the present text of Genesis, but stylistic differences as well as duplications and contradictions in the text have enabled scholars to identify the original versions. The earliest of these two accounts is that of the Yahwist (J), an unknown author who probably wrote during the tenth century B.C. Genesis 6:5–8; 7:1–5, 7–10 (through part of verse 9 is a gloss by the editor who wove the sources together), 12, 16b, 17b, 22–23; 8:2b, 3a, 6–12, 13b, 20–22 belong to this so-called J source. The second account is the product of the exilic or early post-exilic Priestly writer (known to scholars as P.) This account consists of Genesis 6:9–22; 7:6, 11, 13–16a, 17a, 18–21, 24; 8:1–2a, 3b–5, 13a, 14–19; and 9:1–17.9

The fact that these two Biblical accounts have in common so many elements which are not found in the Mesopotamian stories (such as Noah as the name of the hero, the two prologues stating that man’s sin was the reason for the flood, and the absence in both of any attempt to save craftsmen or the elements of man’s civilization) points to their common origin in a tradition which we might call “proto-Israelite.” But despite their common background, there are some significant differences between the accounts of J and P. In J Noah saves seven pairs of every clean animal and one pair each of those which are unclean (7:2–3), while in P there is no distinction between clean and unclean creatures—one pair of each kind is taken aboard the Ark (6:19–20). J states that the Flood was caused by rainfall (7:4) and that it lasted forty days (7:4, 12, 17; 8:6). 019However, P credits the Deluge to rainfall and a bursting forth of “the fountains of tehom” (the waters of the great abyss under the earth,) (Genesis 7:11, 8:2), and states that the Flood lasted for an entire year (7:24; 8:1, 2a, 3b–5, 13a).

It is sometimes assumed that because P was written down much later than J, it must to some extent be dependent on J. However, this assumption is quite probably incorrect. The author of P seems to have been the recipient of a body of traditions which were preserved separately from those of J and which, though written down later, were often as ancient in origin. The differences between the flood stories of J and P were probably the result of a common “proto-Israelite” flood tradition being passed down in oral form among two different segments of the population or in two different areas of Palestine.

The similarities between the Biblical flood stories and the Mesopotamian accounts (particularly the one in the Epic of Gilgamesh) are far greater than those between flood stories found in other parts of the world. Not only do both traditions refer to a universal Deluge of which one man is warned, escaping with his family and representatives of each animal species, but also both contain a divine command to make an ark and to caulk it with bitumen, an account of the landing of the ark on a mountain while the waters recede, the incident of the sending of the birds (a very close parallel), the building of an altar, and the offering of a sacrifice by the hero upon descent from the ark. When all of these similarities are added to the fact that the phrase about the gods or God smelling the sweet savor of the sacrifice is virtually the same in each version, and that both stories 020come from the ancient Near East where widespread interrelations of peoples and cultures is demonstrable, the probability of these similarities being due to chance becomes almost zero.

Thus, it can be safely assumed that the Biblical flood stories and the Mesopotamian traditions are related to one another, but it is impossible at present to reconstruct the exact relationship. How many (if any) intermediate versions stood between the “proto-Israelite” tradition and those of southern Mesopotamia we don’t know. It is clear, though, that the Mesopotamian traditions have temporal priority and that they were the ultimate source of the Biblical versions.

The Genesis flood stories, then, are legends, not history, and attempts to locate the remains of the Ark can result only in a waste of time and money. But the importance of the Biblical flood narratives goes beyond the question of their historicity, for they testify to the convictions of the people who wrote them. Along with other material of mythical or legendary origin (Genesis 1–11, much of it also from Mesopotamia), the traditions about the Flood were used by the Biblical authors to form a prologue for the history of God’s dealings with the people Israel. Although both J and P used material that was ultimately Mesopotamian in origin, the perspective from which they viewed their narratives was quite different from that of Mesopotamia. Historical experience had led the ancient Israelites to believe in an active, covenanting God who seeks to bind his people to Him. This belief was so strong that it not only colored the Israelite view of history, but it also transformed ancient myths and legends and made them an integral part of Israel’s “salvation history.”

According to the Biblical authors, the Flood was sent as a last resort when man had become so sinful that God could do nothing else. It was punishment for moral offenses, and it was deserved. But God, although just, is also a God of mercy, and upon seeing Noah’s offering, he promised never to destroy mankind again (no matter how much man deserves it). Thus, the flood story is used to add another part of the general backdrop against which Israel’s “salvation history” will be played. When even the descendants of the faithful Noah go wrong, God calls a special family (which becomes a people) to serve him and become his instruments. The rest of the Old Testament describes Israel’s struggle with that call.

Thus, looking at the perspective from which the Biblical writers viewed their flood stories, and examining the context into which they placed those stories, one cannot help but feel that the flood tradition has undergone a qualitative change since being removed from Mesopotamia. That the Old Testament contains mythological elements and that it preserved some legendary stories which originated in Mesopotamia or in other cultures of the ancient Near East is to be expected. What is surprising is the degree to which these myths and legends have been transformed by the ancient Israelite conviction that again and again throughout their history a voice has called to them saying:

You are my witnesses … and my servant whom I have chosen,

that you may know and believe me and understand that I am He.

Before me no god was formed, nor shall there be any after me.

I, I am Yahweh, and besides me there is no savior.

Isaiah 43:10–11

A recent Readers’ Digest article which suggests that the remains of Noah’s Ark may yet be found atop Mount Ararat in eastern Turkey has rekindled enormous interest in the quest.1

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Endnotes

G. Gaskill, “The Mystery of Noah’s Ark,” Readers’ Digest, September, 1975—condensed from Christian Herald, August, 1975.

See E. A. Speiser’s translation of the epic in J. B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts, Princeton, 2nd ed., 1955, pp. 72–99, especially pp. 93–95. See also pp. 104–106 for the fragments of the Atrahasis Epic, another Old Babylonian composition containing a flood account.

See, for example, Violet M. Cummings, Noah’s Ark: Fact or Fable?, Creation-Science Research Center, 1972; John Warwick Montgomery, The Quest For Noah’s Ark (Bethany Fellowship, Minneapolis, 1974); John D. Morris, Adventure on Ararat (Institute For Creation Research, San Diego 1973); Rene Noorbergen, The Ark File (Pacific Press Publishing Assoc., Mountain View, Ca., 1974.

See J. C. Whitcomb and H. M. Morris, The Genesis Flood, Presbyterian and Reformed Publishers, 1960, pp. 63–79.