Israel first appears in an epigraphic source (that is, in a surviving ancient document) around 1200 B.C.E.,1 in a stone victory stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah. At the end of this long inscription, almost as an afterthought, the intrepid king informs us that he put an end to “Israel,” a group located somewhere in Palestine, probably in the hill country of what would later be called “Samaria” or “Judah.”

If we attempt to embed Merneptah’s “Israel” in the Biblical story, this first mention of Israel must correspond to the period of Joshua’s conquest or later, during the period of the Judges. Before the time of Joshua, the Bible tells us, Israel was not in Palestine. And much before Joshua, Israel was not even a cohesive group, just a rabble of slaves or a family.

What about the epigraphic documentation concerning Israel’s ancestors as mentioned in the Bible, the forebears of the nation, the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob? Bluntly put, there are no such documents. Nor are there any other archaeological data pointing directly to the Biblical patriarchs. The study of patriarchal Israel more than any other branch of Israelite history lacks a grounding in material culture. Abraham’s pots and pans, Isaac’s domestic architecture and Jacob’s private archives do not exist.

Are we then to deny the existence of Israel’s ancestors and hence the Bronze Age (i.e., pre-1200 B.C.E.) origins of Israel itself? This question of the reality of the patriarchs and the origins of the Israelite nation has seriously concerned Western Biblicists and historians of Israel for some 300 years. This concern can and should be tied to the broader intellectual and theological issues and debates that have preoccupied European intellectuals over this same span of time. I would like to discuss this so-called “patriarchal question” in the context of these European intellectual developments and focus, ultimately, on two intellectual giants whose names are familiar to many BAR readers, William Foxwell Albright and Julius Wellhausen. Finally, within this European tradition, I attempt to answer the patriarchal question.

Sneak preview: The answer regarding Abraham’s historicity is … it depends on what you mean by historicity. But no matter how we regard Abraham, we can answer the related, even more important, question regarding Israel’s origins in time and space. Those beginnings lie beyond our abilities to determine and may be permanently hidden. The origins of an ethnic group—any ethnic group—are, by nature, obscure. Group self-identity is a subtle, largely gradual and uneven process. Nobody was there to record: “I was watching, and one moment, these folks were just hanging around, a crowd, and the next they were an ethnos or a nation.” And perhaps more: “And they will eventually become a major force in the neighborhood/region/world.” If there can be no such record, we cannot define the moment of crystallization, the moment a nation (or ethnos) is born.

But let us return to the struggle regarding the reality of the patriarchal period as it was fought in European intellectual circles. To understand the battle of the titans—the rivalry of the schools of Wellhausen and Albright—their world views must be understood as part of larger intellectual struggles, especially those that found expression in the 19th century, a turbulent time in Western political and intellectual history. On the political level, the 19th century witnessed the formation of important nation-states. It was then that the Italian states coalesced, as did the German. Political ambition was also expressed through territorial expansion, most notably among the nation-states already then united. Thus the 1800s witnessed the continued expansion of French interests, especially under Napoleon, and of the British empire following Napoleon’s defeat. These imperial movements brought the Near East to the attention, not only of the ruling elites, but of the European middle class as well. Here we note that academe and the world of scholarship were middle-class pursuits. They interested neither the poor nor the rich who, for economic reasons, considered institutionalized scholarship largely irrelevant.

In Napoleon’s wake, ancient Egypt was opened up thanks to discoveries such as the Rosetta Stone, which led to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphic. So, modern Egyptology (the study of the ancient civilization of the Nile Valley) was born. At virtually the same time, French and British political and economic interests extended to Mesopotamia and beyond. The lands of ancient Assyria and Babylonia were increasingly opened up by an intelligent, ambitious and tireless series of explorers, diggers, decipherers and looters. With the increasing number of monuments and documents stuffing the British Museum and the Louvre, those theme parks of the imperial middle class, Assyriology (the study of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia) was born. Assyriology and, to a lesser extent, Egyptology increasingly exposed the world of Israel’s origins, the world that the patriarchs were supposed to have inhabited. And archaeology was the tool of that exposure.

Intellectual developments in the 19th century were no less dramatic than the political developments and no less important for the search for the Biblical patriarchs. From the Renaissance on, the hold of an imminent God on the intellectual imagination of the West had become increasingly weakened. As that hold weakened, so did the unquestioned truth of that God’s greatest literary creation, the Torah. The explorations of the physical universe by Copernicus (1473–1543), Galileo (1564–1609) and Kepler (1571–1630) culminated in the great physics of Newton (1642–1727).2 The Age of Reason, for which the Newtonian paradigm was to provide a potent model, spawned famous skeptics of Biblical revelation such as Voltaire (1694–1778).3 The intellectual models based on Newton’s mechanical, timeless universe, however, were replaced in the 19th century by another dominant model: that of biology, the study of living, time-bound nature, a model we associate with the name Charles Darwin (1809–1882).4 The biological paradigm proved a powerful intellectual concept. Ideas such as progress, evolution from simple to complex organisms, mutation and the individuality of species had profound effects in areas far removed from biology, including Marx’s historiography and Frazer’s anthropology of religion. Not the least effect of Darwinism was its explicit challenge to the divinely assured truth of Torah, especially of early parts of Genesis. If Renaissance humanism and Newtonian physics threatened the unique position of Holy Scripture, Darwinian evolution and the associated geological time of Charles Lyell (1797–1875)5 represented a fatal frontal attack in the West on divinely revealed religion. Everywhere, it seemed, the church and related institutions were in full intellectual retreat. Organized religion continued to be practiced, but its conceptual grounding was in the process of collapse.

A counterattack was beginning to be mounted, however. If reason and various scientific models were the weapons causing so much damage to Holy Scripture, then reason must be enlisted in the counterattack, reason joined by the emerging, fresh, new, avant-garde disciplines of Egyptology and Assyriology. If tangible evidence from the earth was being used to dismiss the word of God, then tangible evidence from the lands of the Bible would confirm the word of God. The skeptics would be challenged on their own intellectual ground. It was a daring development, a bold gamble, born of intellectual desperation.

At first, the results were spectacular.6 British, French and, later, American excavations in Iraq, as well as a stunning discovery in ancient Moab, produced monuments and documents that named Biblical persons such as the Assyrian emperors Tiglath-Pileser and Sennacherib, the Moabite king Mesha and the Judahite and Israelite rulers Hezekiah and Omri. Archaeology was resurrecting not only defunct cultures and societies, but the reputation of the Bible itself as both an historical document and true word of God. Perhaps most spectacular of all, the discovery of Assyrian analogues to the Genesis flood story seemed to extend the Bible’s factual reliability back to within 10 generations of Creation itself.

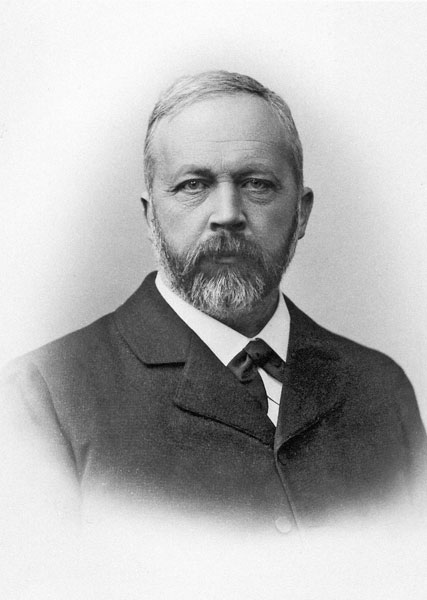

On the crest of these brilliant victories, the existence and truth of Israel’s patriarchs, the nation’s very origins, seemed less doubtful than before. Against this background, two branches emerged of what may be called “archaeology”: the recovery and analysis, in physical and social context, of two kinds of products of man’s past—material artifacts and literary texts. These two schools were epitomized by the two giants whom I mentioned earlier. The archaeology of material remains would be led by one of the intellectual giants of this past century, William Foxwell Albright (1891–1971). And the archaeology of literature, that is, the Biblical text, would be epitomized by one of the giants of the late 19th century, Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918).

Although Albright flourished a half century after Wellhausen, I shall consider them in reverse order, because, intellectually, it is Wellhausen who presents a challenge to Albright.

Several important elements made up Albright’s intellectual personality.7 First of all, he was a believing Christian whose faith was reflected clearly in his magnum opus, From the Stone Age to Christianity.8 The titles to the several sections of the work reveal just how deep-seated his Christian teleological view of life was: “Praeparatio,” “When Israel Was a Child (Hosea 11:1),” “Charisma and Catharsis” and, finally, “In the Fullness of Time … (Galatians 4:4).” Thus, the evolution and progress of history—note the Darwinian concepts—involve the phenomenon of ancient Israel. Israel was a unique mutation, a leap in religion from the natural order of ancient Near Eastern societies. Thus ancient Israel bore within it the seeds of salvation, the ultimate exception to the evolutionary course of history: God made flesh, the phenomenon of Jesus of Nazareth. In this process, Israel was obviously central. And in this centrality, Israel’s origins in the ancient Near East and the emergence of her ancestors, the patriarchs, was a crucial pivot. For although Israel was religiously unique, socially, culturally and even ethnically, it was part of that old and venerable world. The patriarchs and their kin were part of the fabric of the ancient Near East while also transcending it. Therein lay the uniqueness of Israel. The existence of the patriarchs was crucial, absolutely necessary for Albright’s perspective on the course of history.

Albright brought personal qualities to his scholarship: a deep underlying faith in which the saga of Israel played a key role, an abiding sense of evolutionary progress—he recognized the power of the Darwinian model for the study of history—a Christian (and American) sense of hope and the notion that the past could be made knowable in its essentials through scientific exploration undertaken in the present. These characteristics met in an undeniably great mind. Albright worked in Assyriology, Egyptology and ancient history, making important contributions in all these areas. Furthermore, he also made fundamental contributions to archaeological method and to the archaeology of the land of Israel. He brought rigor to his studies and broad learning and imagination to his panoramic perspective. His aim was to place the society of Israel’s patriarchs as described in Genesis in the context of the very ancient Near East that he was helping to reveal, the ancient Near East of potsherds and architectural plans, of cuneiform legal texts and hieroglyphic monuments.

Since Biblical chronology seemed to place the patriarchs in the first half of the second millennium B.C.E., it was there, in the Middle Bronze Age, that Albright directed his focus. And archaeology, the recovery and analysis of the products of man’s past, was the underlying scientific tool in this quest. Albright would seek—and find—datum after datum in the ancient Near Eastern Bronze Age that paralleled—or seemed substantially to parallel—patriarchal features in Genesis.

The excitement and attractiveness of this pursuit, the search for patriarchal Israel, led Albright and some of his peers, such as Cyrus H. Gordon and E.A. Speiser, as well as several generations of their students and followers to take up the challenge. If enough data were collected, the past could be recovered; and if enough parallels between the ancient Near Eastern Bronze Age and Genesis could be adduced, then the historicity of the patriarchs—or at least of patriarchal society as depicted in Genesis—could be assured. The origins of Israel a millennium before the heyday of the ancient Israelite states of Israel and Judah could once and for all be seen, and seen through the microscope of science, not the rose-colored glasses of faith.

And so, from Mari and Nuzi in Mesopotamia, and from Amarna and Beni Hasan in Egypt, and from other sites as well came personal names and laws, customs and beliefs that were then attached to the stories of the ancestors in Genesis. The patriarchs and Israel’s origins entered the historical stage, though where on the stage they were to stand and in what act they were to enter remained troublingly unclear, as we shall see.

Enter Julius Wellhausen, archaeologist of the text rather than the physical artifact. Like Albright (of course, he flourished before Albright), Wellhausen was caught up in the 19th-century intellectual climate. He was affected by the regnant ideas of nationalism, historical progress and the Darwinian notion of evolution, specifically the evolution of organisms from the simple to the complex. He applied this notion, which was at home in the world of nature, to religious institutions as well as to other elements of the man-made world. As individual organisms grow, mature and decay, so, too, do societies and civilizations. Thus, to take a pertinent example, the Jews were once young and vigorous, unself-conscious and spontaneous, expressing their religious impulses simply and innocently. In the course of time, the nation and its religion became rigid, ossified and formalistic—bound to law and minutely spelled-out ritual, rather than to emotionally spontaneous gesture and expression. At long last, Christianity liberated worship of the one God from the stultifying constraints of law, retrieving freshness of worship from stale rite. The church became the new Israel, replacing the husk of what once had been a living, vital nation.

This unedifying and potentially lethal application of Darwinism mixed in with nationalism comprised a strong element in Wellhausen’s Bible-related studies. It was not, however, the most important element. His major contribution was the articulation of the “mature documentary hypothesis” as an explanation of the Torah’s composition.

The documentary hypothesis had its origins, however, not in 19th-century intellectual ferment, but in the 18th century.9 This was the age when Henning Bernhard Witter in 1711 and Jean Astruc in 1753 each independently formulated a consistent, coherent and somewhat efficient alternative to the increasingly untenable idea that Moses wrote the Torah, specifically Genesis.10 Witter and Astruc originated the notion that the proper study of Genesis requires the definition of its constituent elements, and that those elements could be isolated according to the presence or absence of particular features of the text. Proper understanding of the whole was proper understanding of the building blocks of the whole. This mechanistic—some would say reductionist—view of Scripture ultimately derives from a world view influenced by the physics of Isaac Newton.

Wellhausen built on the accomplishments of Astruc’s successors to set forth the principles of authorship of different parts of the Bible, including the Torah. He did this in his masterful and still dazzling Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (1878).11 Wellhausen there summarized and defended the proposition that the Torah, including Genesis, is made up of four main textual strata, or documents. These documents are apparent from internal analysis of the final text. As even the Albrightians would concede, this source analysis of Genesis is both reasonable in its premises and generally persuasive in its main results. Different documents do underlie the present narrative. Assumption of these documents does explain numerous duplications, contradictions and inconsistencies in Genesis.

A crucial element of Wellhausen’s theory and method is its “archaeological” dimension. For Wellhausen recognized that the Bible, as a product of human creativity, is, in effect, an archaeological artifact. Thus, it needs not only to be defined—a series of books in a series of ancient versions and variations—but it needs to be placed in its context, in terms of its function at the time or times of its creation. As historians, we cannot understand the Bible until we wrestle with the issues of motivation in its formation and editing.

As for the patriarchs, Wellhausen would say that before reading Genesis to evaluate Israel’s origins, we must evaluate Genesis in the contexts of its various periods of authorship and redaction. That is required before one may begin using the narrative as a historiographic document. In an oft-cited statement, Wellhausen summarized the results of this process as follows:

The materials here are not mythical but national, and therefore more transparent, and in a certain sense more historical. It is true, we attain no historical knowledge of the patriarchs, but only of the time when the stories about them arose in the Israelite people; this later age is here unconsciously projected, in its inner and its outward features, into hoar antiquity, and is reflected there like a glorified mirage.12

Wellhausen’s results regarding Biblical authorship, that even the earliest tales of the patriarchs should be dated late, deep into the Iron Age, means that the patriarchal narratives are primarily evidence for the world view of the period of the Israelite monarchy in which most of the documents were written. The same narratives are secondary evidence—if they are evidence at all—for the age that is supposedly being described.

Wellhausen’s observations were dazzlingly simple and inevitably right. Whether or not the text contains older traditions, it is a creation of a certain period and is first a primary source for that period. This is a clear and well-deserved commonplace in the thoughts of historians of antiquity and more recent periods alike.

The methodological implication of this perspective for Albrightian archaeology is clear: it undermines it. Of course, Albright and his followers came well after Wellhausen, and Albright had the good sense not to dispute the results of the by-then already classical literary analysis of Genesis. But while accepting the results of this textual archaeology of the Bible, Albrightians attempted to neutralize its impact by asserting that literary analysis is not central to historical reconstruction based on the text. This is so, it was claimed, because though the documents were late—that is, from the Iron Age—the traditions contained in them are early. Thus, one can have early history in late documents. Defense of this assertion meant that it was urgent as well as desirable to be able to demonstrate that what is contained in Genesis harks back to Bronze Age realities.

Albright and Wellhausen both emphasized archaeology, but only Wellhausen addressed the patriarchal issue with methodological directness. His was the archaeology of the text, a text describing the patriarchs, whereas Albright’s was the archaeology of the field, and the “field” has never yielded mention of the Biblical patriarchs.

The counterattack mounted by the Albright school consisted, as mentioned earlier, of establishing parallels between the society of the patriarchs and the world of the Bronze Age, especially the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1600 B.C.E.), and especially the world of Mesopotamia, in which lay Abraham’s homeland, Ur.

The enterprise was badly flawed.

By focusing both on Mesopotamia and on the first half—or even two-thirds—of the second millennium, the experiment was biased. In space, the entire Near East, and, in time, the second millennium and the first, down to the time of the earliest Genesis manuscript should have been examined. Only in this way might all significant parallels have been detected. Only in this way might such parallels be noted as exclusively from one small period (presumably that of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob) or not. Accepting Wellhausen but then ignoring him condemned the Albright approach from the outset. Genesis was never seriously viewed as a primary source for the periods in which it was created.

Yet even if this bias is ignored, the parallels adduced by the Albrightians for patriarchal society derive from southernmost Iraq to southern Turkey to coastal Syria. The parallels extend in time from the end of the third millennium (if not earlier) to the 14th century B.C.E. A pattern consisting of most of the Fertile Crescent and over 600 years is no pattern at all. So even if one ignores the bias against the first millennium, no particular second-millennium space and time assert themselves.

But let us assume that, in addition to there being no bias, there is a pattern. Allegedly, significant parallels have indeed been asserted, especially from the 18th-century upper Euphrates or the 15th-century area around modern Kirkuk. Nevertheless, the search for the patriarchs fails at yet another level: that of the parallels themselves. Many of the parallels are simply wrong. They depend, at times, on adjusting the Mesopotamian data to fit the Biblical, or adjusting the Biblical data to fit the Mesopotamian, or adjusting both to force agreement. For example, parallels from the Kirkuk region of northern Iraq are allegedly found in the Nuzi texts. Both Genesis and Nuzi are supposed to describe a peculiar legal status for woman as simultaneously wife and sister to her husband. Both Genesis and Nuzi allegedly attest that possession of the household gods ensures inheritance rights. Description of such “parallels” abound in E.A Speiser’s well-known commentary on Genesis.13 One of many necessary correctives appears in B.L. Eichler, “Nuzi,” in The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Supplementary Volume.14

Moreover, some of the parallels, though correct, are so general or so common as to be useless for purposes of fixing a patriarchal age. Thus, the name Abram and his hometown of Ur are attested in the Old Babylonian period (i.e., 2000–1600 B.C.E.), but they are attested much later, as well. Another example: preferential treatment of first-born sons and exceptions to that preference are ubiquitous throughout the Near East and throughout the ancient period.

There are, indeed, significant parallels between the Genesis patriarchs and the ancient Near East, but these appear to be Iron Age parallels, in just the time period Wellhausen places the authorship and editing of Genesis. Thus, for example, the patriarchs’ camels, Chaldean Ur and Philistines in Palestine are all Iron Age—not Bronze Age—realities.

Thus, Albright’s attempt to fit the patriarchs into the Near Eastern Bronze Age failed and today has been all but universally abandoned.

Having made this declaration, let me also enter a fray familiar—too familiar—to readers of BAR. I AM NOT A BIBLICAL MINIMALIST. The patriarchal problem is qualitatively different from the problem of later Israelite history and its relation to the Bible. For most later history, we may compare the epigraphic with the Biblical; for the patriarchal period, we may not. So, those who lump together an unhistorical patriarchal period with a similar conclusion regarding the settlement—especially the monarchy—and write as if the two areas were a seamless part of the same issue are conceptually mistaken. They are not part of the same problem at all. If I reach largely negative conclusions regarding patriarchs and Israel’s origins, it most certainly does not follow that one dismisses Biblical statements regarding the periods of the settlement in Canaan, the united and then divided monarchies and the exilic and post-exilic periods of Israel’s history.

What, finally, were Israel’s origins? The ethnic identity of Israel may have been achieved toward the end of the Late Bronze Age as the result of economic and political turmoil. The Israelite nation may have been formed out of Canaanite highland herdsmen, Habiru bands,a elements of the Sea Peoplesb or coastal lower classes, even immigrants from the southeast, perhaps even from Egypt. The scant early evidence describes these peoples, as well as perhaps Yahweh-worshiping Shasu, a group called Asher in the Galilee and another called Gad in the trans-Jordan, as well as the certain mention of Israel in Palestine by King Merneptah with which I began.

So much for Israelite origins. For the patriarchs, we are, ultimately, thrown back on the only tangible, archaeological item of significance, the wondrous tales embedded in the sources of Genesis. As archaeologists of the text, we must again look to the context of these tales. That context is the first millennium. Somewhere here is the world of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, as conceived in the minds of the great writers of Israel.

And so we revisit the question posed near the start of this article regarding Abraham’s historicity: He may not have existed in body, but he and the other patriarchs became part of the identity, the glory of the past and the hope for the future for the people called Israel.15

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Abraham Malamat, “Let My People Go and Go and Go and Go,” BAR 24:01.

Trude Dothan, “What We Know About the Philistines,” BAR 08:04.

Endnotes

The Merneptah Stele thus dates to the very end of the Late Bronze Age (1600–1200 B.C.E.) or the start of the Iron Age (1200–586 B.C.E.).

See, conveniently, I. Bernard Cohen, The Birth of a New Physics, rev. ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1985). Newton’s Principia was published in 1687.

Amongst Voltaire’s numerous observations on Israel and the Bible, see his evaluations in chapter 4 of An Important Study by Lord Bolingbroke, or The Fall of Fanaticism: “I conjecture that Ezra forged all these Tales of a Tub on his return from captivity. He wrote them in cuneiform, in the jargon of the country just as today’s northern Ireland peasants would write in English characters.”

And: “[Assume] that the Pentateuch is by Moses. So, my friends, what would be proved? That Moses was a fool. One thing is sure, that today I would have a man who wrote similar extravagances committed to Bedlam” (Voltaire on Religion: Selected Writings, trans. Kenneth W. Applegate [New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1974], pp. 105, 107–108).

For these developments, see Katherine Eugenia Jones, “Backward Glance: Americans at Nippur,” BAR 24:06 and Mogens Trolle Larsen, “The ‘Babel/Bible’ Controversy and Its Aftermath,” in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 1, ed. Jack M. Sasson, et al. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1995), pp. 97–99.

Aspects of Albright’s life and thought are treated by Leona Glidden Running and David Noel Freedman, William Foxwell Albright: A Twentieth Century Genius (New York: Morgan Press, 1975); and, in a very different way, in Burke O. Long, Planting and Reaping Albright: Politics, Ideology, and Interpreting the Bible (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

William Foxwell Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1940). An eloquent statement of Albright’s faith comes in the last sentence of the volume: “We need reawakening of faith in the God of the majestic theophany on Mount Sinai, in the God of Elijah’s vision at Horeb, in the God of the Jewish exiles in Babylonia, in the God of the Agony at Gethsemane…” (from the second edition [Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1957], p. 403).

Cf. the somewhat similar and different perspective of Jack M. Sasson, “On Choosing Models for Recreating Israelite Pre-Monarchic History,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 21 (1981), pp. 8–9.

See Otto Eissfeldt, The Old Testament: An Introduction, trans. P.R. Ackroyd (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), pp. 160–162. Eissfeldt’s treatment of this period of Biblical criticism is fuller than those of more recent introductions to the Bible.

The edition here used is Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1957).

A fuller version of this article appeared as “Historiographic Reflections on Israel’s Origins: The Rise and Fall of the Patriarchal Age,” in Hayim and Miriam Tadmor Volume (=Eretz Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies, Vol. 27), ed. Israel Eph‘al., Amnon Ben-Tor and Peter Machinist (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, etc., 2003), pp. 120–128.