The Abraham cycle (Genesis 11:27–25:11) is a drama of increasing tension—a tension between Yahweh’s promise that Abram would have an heir, indeed, that he would become the father of many nations, and the threat to the fulfillment of that promise by a series of crises. The literary technique employed is what Peter Ellis calls “the obstacle story”:

Few literary techniques have enjoyed so universal and perennial a vogue as the obstacle story. It is found in ancient and modern literature from the Gilgamesh epic and the Odyssey to the Perils of Pauline and the latest novel. Its character is episodal. [The episodes are] not self-contained but find [their] raison d’être in relation to the larger story or narrative of which [they are] a part. [The] purpose is to arouse suspense and sustain interest by recounting episodes which threaten or retard the fulfillment of what the reader either suspects or hopes or knows to be the ending of the story.1

What ties the entire Abraham cycle together is the problem of an heir. Yahweh’s promise of posterity to Abram (Genesis 12:2) highlights the question: Who will be Abram’s heir?

Although this problem runs through the entire cycle as a leitmotif, it is not the only issue. A subtheme relates to the promise of the land of Canaan. Throughout the cycle, we are reminded of the delay: “At that time the Canaanites and the Perizzites lived in the land” (Genesis 13:7; cf. 12:6, 15:19, 20). Yahweh’s command to “walk through the length and breadth of the land, for I will give it to you” (Genesis 13:17; cf. 12:6), underscores the fact that the only portion of land Abram owned outright was a burial plot at Machpelah, which he bought to bury his wife Sarah (Genesis 23:17–20). His life as a pastoral semi-nomad poignantly emphasizes the great gulf between promise and fulfillment. When, however, we inquire as to the leading theme of the Abraham cycle, we have no hesitation: it is the problem of an heir.

Even before Abram’s call in Genesis 12:1, we are told that “Sarai [as she was then named] was barren; she had no child” (Genesis 11:30). Following hard on the heels of this problem comes God’s promise, “I will make of you a great nation” (Genesis 12:2). Thus the tension between the promise of God and the problem of Abram.

The author skillfully and artistically maintains this tension throughout the entire cycle by a series of eight crises. Each crisis threatens to revoke the promise. Abraham and Sarah live out their lives in this narrative world of despair and hope. Occasionally, they illustrate the folly of human initiatives, but ultimately they triumphantly testify to the faithfulness of Yahweh in keeping his covenant promise. Still, by the time the cycle has run its course, the fulfillment of the promise is only partial: Isaac must carry on the promise, Jacob must survive his brother’s murderous designs, Jacob’s sons must survive a famine in Canaan followed by bondage in Egypt, and so on. In a sense, the entire Hebrew Scriptures carry forward this tension between promise and fulfillment.

The story of Abraham’s relationship to his nephew Lot, to which I will give special attention in this article, should be understood in the context of this problem of an heir. Lot has been with his uncle Abram since they lived together in Ur of the Chaldees (Genesis 11:31). The episode in Genesis 13 involving Lot’s separation from Abram is indeed the second crisis.

The first crisis is occasioned by a drought in the Promised Land shortly after they arrive there. Israel, like southern California, has a two-season climate: a rainy season, running from October to April; and a hot, dry season, running from June through September (September and May are transitional months). Most of the rain falls between December and February. The success of the farmer and herder, however, depends on the critical “early rain” (October-November) and the “later rain” (March-April) (see Deuteronomy 11:14). The former softens the ground, allowing the farmer to plow and plant his seed. The latter gives the emerging crops a needed boost before the long, rainless summer sets in. Failure at either end spells disaster. Shortly after Abram and Lot arrive in Canaan, they experience what must have been an especially severe drought. Little or no grass is available for their sizable flocks and herds. To save their livestock, they must head for the Nile River delta. This Abram does, but not without some misgivings.

Abram fears that the Egyptians will murder him for his beautiful wife Sarai, so he passes her off as his sister.2 Pharaoh, enamored by Sarai’s beauty, takes her into his harem. For his part, Abram is treated as a highly regarded tribal chieftain and he becomes the recipient of Pharaoh’s largesse (Genesis 12:16). Only divine intervention reunites Abram with his wife. Abram, however, must own up to his duplicity before Pharaoh and suffer the indignity of being unceremoniously deported from the country (Genesis 12:19–20). (Abram’s brief sojourn in Egypt is a preview of coming attractions. There will be another, longer stay by the Hebrews in Egypt, where they will be enslaved, but again they will leave with a considerable amount of Egyptian wealth [Exodus 12:25–36].)a

The next crisis involves Lot. Their flocks and herds have grown to such an extent that the land can no longer support both Abram and Lot; moreover, there is strife between the herders of the two men (Genesis 13:6–7). To settle the matter, Abram proposes that the “land” be divided (Genesis 13:8–9). Abram gives his nephew first choice, and Lot chooses the well-watered plain of the Jordan River (Genesis 13:10–11).

One common interpretation of the story is that Lot simply chooses the most desirable portion of the Promised Land. On this reading, Lot, an ungrateful opportunist, forces his uncle to live the rugged life of a semi-nomad rather than the more sedate life of a city dweller in the oasis of the Jordan Valley—a kind of Near East Palm Springs!

Other commentators argue that the real point of the story is that the promise of the land of Canaan to Abram and his offspring hangs in the balance, owing to Abram’s magnanimous gesture in allowing Lot to have the first choice. In this interpretation, the land that Lot chooses is not in Canaan. Had Lot chosen the land of Canaan, so this interpretation goes, Abram would have been exiled to the plain of the Jordan. Providentially, Lot does not select the land of Canaan and thus God’s promise to Abram is secured.

Neither of these interpretations focuses on the real issue at stake—the problem of an heir. That is the context in which this episode must be understood. I agree with the second interpretation above that the land Lot chooses is not a part of the Promised Land. But this choice must be understood in the context of the overarching narrative framework.

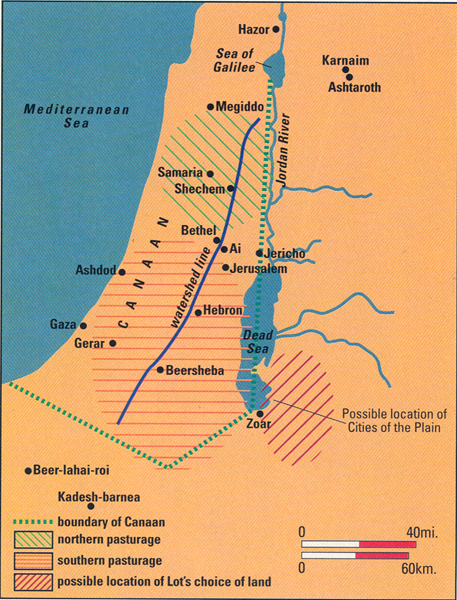

To appreciate the implication of Lot’s choice, we must understand a little of what scholars call historical geography. As the Genesis narratives indicate, the land of Canaan included two primary regions where the patriarchs grazed their flocks—one in the north and one in the south, as shown by the green and yellow circles west of the Jordan on the map . The northern area centered on Shechem (Genesis 12:6, 33:18–34:31, 37:12–17), with the Bethel-Ai region as the southern boundary. The southern area included Hebron/Mamre and the still more southerly region around Beersheba and Gerar (Genesis 12:9; 13:1, 18; 20:1; etc.). The two areas were effectively connected by the watershed line, the mountainous spine that runs through central Canaan. Movement between the two major pasturages followed this time-honored ridge route.

Abram and Lot make their agreement between Bethel and Ai, in the heart of Canaan. Abram offers Lot either the northern area or the southern area. Abram permits Lot to choose the portion of “the whole land” (kol-ha’

Moreover, the biblical text is clear that the eastern boundary of Canaan is the Jordan River from its exit at the Sea of Galilee (the Kinnereth) to the Dead Sea (Salt Sea); from the southeastern end of the Dead Sea the border ran in a southwesterly direction toward Kadesh Barnea and then turned toward the Mediterranean, running along the Brook (or Wadi) of Egypt (cf. Numbers 34:1–29; Joshua 15:1–14; Ezekiel 47:13–20). In Genesis 14, as we shall see, Abram and Lot are involved in a war fought against the Cities of the Plain, which form a discrete political unit, apart from the cities of Canaan.

The actual location of the notorious Cities of the Plain has been much mooted. Until recently, most scholars assumed that, if any such cities ever existed, they must have been located beneath the waters of the southern end of the Dead Sea.3 Now, however, Walter Rast and Thomas Schaub have cautiously advanced a new location:4 they suggest five sites on the eastern side of the Ghor (the plain south of the Dead Sea).b Each site displays a thick destruction layer dated to either the end of Early Bronze III or the beginning of Early Bronze IV (c. 2350 B.C.E.). Whether or not these are the Cities of the Plain referred to in the Bible, the biblical tradition clearly indicates that they formed a distinct geopolitical entity, separate from the land of Canaan.

With this geographical background, we may better appreciate the import of the episode: Lot chooses a portion outside the Promised Land.

But there is more to it than this: Until this time, Uncle Abram had acted as a surrogate father to Lot. Lot’s father, Haran, had died in Ur (Genesis 11:28). Lot went with Abram from Ur to Haran and then to the land of Canaan (Genesis 11:31, 12:4). Throughout chapters 12 and 13, the relationship between Abram and Lot is a close one. The text easily allows us to infer Abram’s sense of responsibility for his nephew. Remember that Abram was otherwise childless. Mesopotamian law codes allowed for the adoption of an heir in the case of childlessness.5 In all probability Abram regarded Lot as his heir.6

Abram’s first solution to the problem of an heir, therefore, was to take Lot as his heir. Let’s call this Plan A. When Abram’s heir-apparent virtually eliminates himself from the promise by leaving the land of Canaan, Abram is without an heir. Plan A is scrapped. Yet, just at this juncture (“after Lot had separated from him” [Genesis 13:14]), Yahweh reaffirms the promise of the land to Abram’s offspring (“your offspring” [Genesis 13:15]).

The third crisis finds Abram entangled in a Middle Eastern war. Genesis 14 describes the war near the Dead Sea between an alliance of the kings of the five Cities of the Plain and an alliance of Mesopotamian kings. In the course of battle, Lot is captured and taken prisoner. When Abram, now at Mamre, hears of this, he takes 318 retainers with him to rescue Lot. Although the rescue effort succeeds, Abram exposes himself to the endemic plague of the region—revenge and retaliation.7 Fear of retaliation provides the backdrop for the divine oracle of Genesis 15:1: “Do not be afraid, Abram. I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.” Yahweh will not abandon his covenant partner, and the Mesopotamian coalition never returns to settle the score. The third crisis is over.

But Abraham still does not have an heir, as he immediately reminds God: “O Lord God, what will you give me, for I continue childless?” (Genesis 15:2). Apparently Abram resorts to another human initiative—the adoption of one of his household slaves, Eliezer, as his heir: “The heir of my house is Eliezer of Damascus…A slave born in my house is to be my heir,” he says (Genesis 15:2–3). We might call this Plan B. To Abram’s surprise, however, this initiative, too, is set aside with God’s startling announcement: “This man shall not be your heir; no one but your own issue shall be your heir” (Genesis 15:4). The Lord then expands the promise to include innumerable descendants and confirms it in a symbolic, covenant ratification ceremony (Genesis 15:7–21). In one of the great moments in biblical history, Yahweh pledges himself unconditionally to fulfill the covenant promise: “To your descendants I give this land” (Genesis 15:18).

But of course Abram still has no descendants. Like a chime, the narrator immediately reminds us of the great problem of faith: “Now Sarai, Abram’s wife, bore him no children” (Genesis 16:1). Another human initiative, this time sponsored by Sarai, sets the stage for the fourth crisis. Sarai will provide an heir not through her own body, but through her handmaid Hagar (Genesis 16:2). Sarai resorts to the legally accepted procedure of concubinage to assure a male heir.8 This we might call Plan C—Sarai’s contribution to the nagging problem of childlessness.

But just when things begin to look promising, and Hagar becomes pregnant, a conflict develops between the secondary wife and her mistress. Hagar may well have harbored notions of replacing Sarai as the primary wife. Sarai is given the authority to discipline the upstart Hagar severely.9 Although pregnant, Hagar flees into the unforgiving desert south of Beersheba. The survival of Hagar—and her unborn child—is at stake. Will the potential heir perish? Again the Lord intervenes. An angel of the Lord tells Hagar to “return to your mistress and submit to her” (Genesis 16:9); the angel promises Hagar that her descendants shall be a multitude. Hagar returns and bears Ishmael.

Following this episode, Yahweh reaffirms his promise to Abram, the fifth such affirmation (Genesis 17:1–8). Abram’s name is changed to Abraham (apparently the narrator understands “Abraham” to mean “ancestor of a multitude”; the new name thus reflects the covenant promise).

In addition, a new element is instituted as a sign of the covenant relationship—Abraham is circumcised and the commandment of circumcision is imposed on all his offspring throughout the generations as a sign of the covenant (Genesis 17:9–27).

At this point, Ishmael appears to be Abraham’s heir. Indeed, Abraham seems ready to accept this: “Abraham said to God, ‘O that Ishmael might live in your sight!’” (Genesis 17:18). Then follows the astonishing promise that Sarah (whose name has been changed from Sarai) will bear Abraham’s heir: “God said, ‘No, but your wife Sarah shall bear you a son, and you shall name him Isaac’” (Genesis 17:19). Ishmael is rejected as the heir to the covenant promise. Plan C is effectively shelved.

Chapters 18 and 19 provide an interlude in the development of the story line. Among other things, they prolong the suspense. Chapter 18 describes the visit of the angels who prophecy that Sarah will give birth to a son even though she is now about 90 years old (Genesis 17:17). God also confides in Abraham about his plan to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah; Abraham bargains with God to save the cities, but not even ten righteous men can be found there. In chapter 19, the angels visit Lot in Sodom and provide for his escape before the city is destroyed. Lot’s incestuous relationship with his daughters results in the birth of the ancestors of Israel’s hated enemies, the Ammonites and the Moabites.

For our purposes, however, the important point is the announcement that Sarah will give birth to a son, despite her advanced age and the fact that “it has ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women” (Genesis 18:11). A rhetorical question accompanies the announcement: “Is anything too difficult for the Lord?” (Genesis 18:14a). Chapter 20 plunges us into the fifth crisis. Shortly after the announcement of the birth-to-be, Sarah winds up in another man’s harem! Abraham has again passed off his wife as his sister—this time to Abimelech, the king of Gerar. Readers may be forgiven for wondering how Abimelech could find the 90-year-old Sarah so attractive. It seems too cynical to say it was purely a political marriage, and too incredible to suggest something like Oil of Olay—some things are best left unexplained! The storyline leads us to assume, however, that if a son is born, he will be reckoned as Abimelech’s heir, not Abraham’s. Yahweh intervenes yet another time, however. He comes to Abimelech in a dream and tells him that Sarah is really Abraham’s wife. Through God’s intervention (perhaps through some sexual dysfunction), Abimelech was prevented from having intercourse with Sarah (“It was I who kept you from sinning,” God tells Abimelech in a dream; after Sarah is returned to Abraham, the text tells us, “God healed Abimelech, and also healed his wife and female slaves so that they bore children” [Genesis 20:6, 17]). In any event, Sarah is returned to Abraham.

As chapter 21 opens, the tension that has been sustained for so long eases: “The Lord dealt with Sarah as he had said, and the Lord did for Sarah as he had promised. Sarah conceived and bore Abraham a son in his old age” (Genesis 21:1–2). All is not well, however. Before long, the status of Ishmael vis-à-vis Isaac becomes a divisive issue in Abraham’s household and provokes the sixth crisis. Though it grieves Abraham, at the insistence of Sarah he disinherits and dismisses Ishmael. Apparently, Abraham grants Hagar and her son their freedom as compensation. This clears the field: There are no potential rivals to Isaac as Abraham’s sole heir.

The seventh crisis comes as a shock. It comes when least expected. And it is unspeakable. After all obstacles have been surmounted and all potential rivals eliminated, God demands Abraham’s only son as a burnt offering. For Abraham, this is the moment of truth. Can Abraham trust God to fulfill his promise despite this command, which seems to negate everything God stands for? We plod with Abraham up the slopes of Mt. Moriah, step by tortured step. The drama reaches its climax in the uplifted knife of Abraham. Suddenly, God speaks: “Because you have done this, and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will indeed bless you, and I will make your offspring as numerous as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore” (Genesis 22:16–17).

God’s intervention and the reaffirmation of his promise would seem to conclude the Abraham cycle at the moment when faith triumphs over all obstacles. In what may appear to be an anticlimactic episode, however, the narrative continues. Abraham’s beloved wife Sarah dies. The promise of the land, we are reminded, has not been fulfilled. Abraham must purchase some land in which to bury her: “I am a stranger,” he says, “an alien residing among you; give me property among you for a burying place” (Genesis 23:4). Abraham purchases Machpelah for 400 silver shekels. This is the only part of Canaan for which he can produce a deed!

The eighth and final crisis concerns finding a bride for Isaac (Genesis 24). Isaac must “not get a wife…from the daughters of the Canaanites among whom I live,” says Abraham (Genesis 24:3). He decides to send his trusted servant (is this Eliezer?) back to Mesopotamia to get a wife for Isaac among Abraham’s own kindred. The problem is expressed by the servant: What if she won’t come to Canaan? Should I then bring Isaac back to the land from which you came? the servant asks Abraham (Genesis 24:5). The answer is an emphatic no. Isaac must stay in the land of promise and must not marry a Canaanite woman.

Happily, when Rebekah is asked whether she will come to Canaan to be Isaac’s wife, she agrees.

The Abraham cycle ends with the statement that “Abraham gave all that he had to Isaac” (Genesis 25:5). The heir assumes his inheritance.

Long ago, the story began with Sarai’s barrenness: “Now Sarai was barren; she had no child” (Genesis 11:30). It appropriately concludes with these words: “After the death of Abraham, God blessed his son Isaac” (Genesis 25:11).

The Abraham cycle underscores Yahweh’s faithfulness to his covenant promise. It demonstrates that Israel exists only because of divine intervention. This divine initiative, however, calls for a response—a response of faith and commitment. Abraham is supremely a man of faith.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

The Egyptians reclaimed a great amount of Israelite treasure when Pharoah Shishak invaded the Land of Israel several hundred years later ( see 1 Kings 14:25–26).

Endnotes

Ephraim A. Speiser’s interpretation of the sistership documents of Nuzi and their relationship to Genesis is defended in his commentary, Genesis, The Anchor Bible Series (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964), pp. 91–92. This view is now rejected by most scholars. See Cecil J. Mullo Weir, “The Alleged Hurrian Wife-Sister Motif in Genesis,” Transactions of the Glasgow University Oriental Society 22 (1967), pp. 14–25.

See James P. Harland, “Sodom and Gomorrah: The Location and Destruction of the Cities of the Plain,” Biblical Archaeologist (BA) 5 (1942), pp. 17–32, and BA 6 (1943), pp. 41–54.

Walter E. Rast and R. Thomas Schaub, Survey of the Southeastern Plain of the Dead Sea, 1973, Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 19 (1974). See also Willem C. van Hattem, “Once Again: Sodom and Gomorrah,” Biblical Archaeologist 44 (1981), pp. 87–92; Rast and Schaub, “On the New Site Identifications for Sodom and Gomorrah,” in Queries & Comments BAR 07:01.

See James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with supplement (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969) (ANET), p. 220, for an example of adoption at Nuzi, and p. 174 (sections 185–193) for adoption documents in Hammurabi’s law code. See also Sabatino Moscati, Ancient Semitic Civilizations (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1957), p. 83, and Ephraim A. Speiser, Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 10 (1930), pp. 7–13. For an example of a man at Ugarit who adopted his grandson, see Isaac Mendelsohn, “A Ugaritic Parallel to the Adoption of Ephraim and Manasseh,” Israel Exploration Journal 9 (1959), pp. 180–183.

A point made by Rashi in his commentary on the Pentateuch and cited in The Soncino Chumash (London: Soncino, 1947), p. 64.