Archaeological artifacts do not interpret themselves. Here’s a case in point: Some 40 relatively small altars were found in at least nine sites in Palestine. After most scholars agreed that they were intended for burning incense, they were designated “incense altars.” I too once subscribed to the belief that they were incense altars, but am now convinced that is wrong.

But not simply wrong: This faulty interpretation leads to a misunderstanding regarding ancient Israel’s cultic practices.

These altars have turned up in excavations since 1912. The most recent and largest assemblage ever found, approximately 20 altars, was discovered at the famous Philistine site of Ekron (Tel Miqne) in an ongoing excavation jointly led by Trude Dothan of the Hebrew University and Seymour Gitin of the W. F. Albright School for Archaeological Research in Jerusalem. The recovery of such a large assemblage naturally leads to renewed interest in these altars.

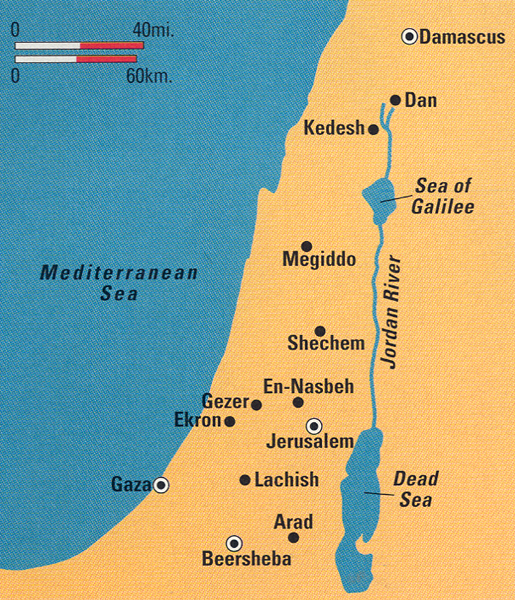

Ekron is not the only site where they have appeared in considerable numbers. Nine were recovered from Megiddo, and six have shown up at Tel Dan, in the ongoing excavation led by Avraham Biran of Hebrew Union College. One was even discovered in Nineveh in Assyria, a curious fact to which we will return.

These altars vary slightly in size; most range from 6 inches to 26 inches in height. Most have horns atop each corner, a feature typical of altars. The majority are of stone, mostly limestone, with a few basalt specimens and one known ceramic altar (from Tell en-Nasbeh, just north of Jerusalem).

They are defined as incense altars primarily due to their startling similarity in form to the incense altar the Bible describes as standing before the veil (parokhet) that screened the Holy of Holies in the desert Tabernacle (Exodus 30:1–6, 37:25–28). Unlike the excavated altars, the Tabernacle altar was covered with gold; but other similarities are striking. The Tabernacle altar is described as having horns, and even its decoration is similar: The Bible tells us that a gold molding (zer) enclosed the shaft (Exodus 30:3, 37:26); the excavated altars are almost all decorated with flat or rounded bands enclosing the shaft.

Indeed, the Bible states that the Tabernacle altar was used for burning incense no less than twice a day: “On it Aaron shall burn aromatic incense; he shall burn it every morning when he tends the lamps, and Aaron shall burn it at twilight when he lights the lamps—a regular incense offering before the Lord throughout the ages” (Exodus 30:7–8). Although described as an accoutrement of the desert Tabernacle, this altar is commonly believed to represent an analogous altar in Solomon’s Temple. The description of the Tabernacle is generally considered to be an ideal retrojection of Solomon’s Temple against the background of the journey from Sinai to Canaan. The plan of the desert Tabernacle is the same as that of Solomon’s Temple, and a gold altar actually stood in Solomon’s Temple in front of the debir, the inner sanctum, or Holy of Holies (1 Kings 7:48; compare 6:20–21). Although incense-burning on that Temple altar is not directly mentioned, Isaiah’s vision describes one of the seraphim taking a burning coal from the altar inside the Temple (Isaiah 6:6).

Whether incense was used in the most ancient Israelite rituals has been debated in modern research. At first, the early use of incense was denied, since the passages that refer to incense-burning in the Pentateuch (in the “Priestly Source”) were considered to be of late origin.a The first reference to the use of incense in Israelite cult practices was taken to be Jeremiah 6:20: “What good is it to me if frankincense is brought from Sheba?” Then the appearance of “incense altars” in archaeological finds was regarded by many scholars as proof that incense did have a place in the ancient Israelite cult. Still later, some argued that the “altars” in question are actually objects of another sort. Nevertheless, it is incontestable that most of them are actual altars with cultic contexts. At least some (those from Dan, Kedesh in the Jezreel Valley, Megiddo and Lachish) were found in Israelite layers. Yet I think that these altars in themselves do not prove early cultic use of incense in ancient Israel. This is not because I deny that possibility, but because it now seems highly improbable to me that these altars were used for burning incense.

My suspicions were initially aroused because most of these altars (with few exceptions noted below) show neither traces of burning nor any organic remains. This is so for every shape of altar—whether flat, slightly concave or depressed in the square within the four horns. Most of these altars do not appear to have been used as fire altars at all.

True, a few of the 40 had a fatty residue on them (two hornless columns in Arad), or a heavily calcined layer (one of the altars at Dan has a layer a few centimeters thick), or traces of fire (two altars in Room 244 at Dan, one at Ekron).1 I would be surprised, however, if any of these remains provides evidence of incense burning.2 If these altars were intended for burning incense, we would expect more substantial and more uniform signs of that activity.

Another point that makes it doubtful these altars were used for incense is the cost of incense in the biblical period. The Bible, as well as other ancient Near Eastern and some classical sources, mentions the rarity and costliness of incense. The principal component of incense was frankincense (see Exodus 30:34). Both frankincense trees and myrrh trees (which produce another exotic perfume) could grow only in limited areas on both sides of the Gulf of Aden—on the southern and southeastern end of the Arabian peninsula (Hadhramaut and Dhofar districts) and, on the other side of the Gulf, on the northern end of Somalia. The Egyptian queen Hatshepsut (1490–1468 B.C.E.) attempted to acclimatize these trees to Egypt but was apparently unsuccessful.

Frankincense and myrrh were transported by caravans from their production areas to Israel and adjacent areas (compare 1 Kings 10:2; Isaiah 60:6; Jeremiah 6:20), as well as to Egypt and Mesopotamia. Caravans and ships traveled along well-established routes by land or by sea. The land caravans used camels for transport. The best known of these ancient routes was the “incense route,” probably fixed shortly after the domestication of the camel around the 12th century B.C.E. The “incense route” began at Shabwa in the Arabian Hadhramaut and from there went on to Timna, Marib and Ma‘in, running parallel to the Red Sea coast and ending at Gaza. Other branches of the route turned from Eilat to Egypt and from the El-Ola oasis toward Petra and Damascus. At every way station, the local chieftain would claim his share in taxes, impose levies on the right of passage or the right to stop overnight, and charge for water and fodder.3 By the time the spices reached their destination, costs—and therefore prices—had soared. The trade in spices brought great wealth to the South Arabian kingdoms, but, when this trade ended, their economies collapsed and living conditions precipitously declined.4

No wonder the spices brought from South Arabia, especially frankincense, became synonymous with gold and precious stones and are often described as royal treasures (1 Kings 10:2, 10; 2 Kings 20:13; Isaiah 60:6; Matthew 2:11). It is hardly imaginable that ordinary people in Judah and Israel regularly kept altars to burn incense from distant Southern Arabia. It should also be noted that many of the Ekron altars—the largest of the assemblages—were found in the city’s industrial area; two were found in the domestic zone.5

Incense was used not only for cultic purposes, but also for a variety of secular needs, such as perfuming the body (Song of Songs 4:6, 14; compare Psalms 45:9) or the bed (Song of Songs 3:6; compare Proverbs 7:17), as well as for medical treatment,6 and even for spicing wine to make it more intoxicating.7 It was also used to freshen and sweeten the stale air of poorly ventilated ancient houses (see Exodus 30:37–38 and Proverbs 27:9). Needless to say, incense for secular purposes required daily and prolonged use—which only the wealthiest could afford.

Just as secular use of incense was doubtless confined to the very rich, so cultic incense-burning was confined to the Jerusalem Temple, the Royal Temple of the Judahite Kingdom. The excavated altars were provincial in character, however, and their formal similarity to the gold altar described in Exodus is not enough to establish that incense was burned on them too. The biblical text presupposes that the regular and continuous use of incense for cult purposes is restricted to the central Temple (which, in turn, is reflected in the Tabernacle). To be sure, towards the end of the First Temple period (sixth century B.C.E.) ordinary folk could manage to bring a pinch of frankincense and offer it in Jerusalem (see Jeremiah 17:26, 41:5). However, the conspicuous, twice-a-day use of incense described in the desert Tabernacle is in keeping with the splendid materials adorning it—gold and silver and cloths of violet, purple and scarlet—which are combined in the Tabernacle’s design, in its vessels and in the garments of the High Priest. In the Judahite kingdom, such a concentration of wealth could exist only in the royal domain or the nearby house of God.

Still another factor casts doubt on the use of these excavated altars for burning incense: the location where some were found. The gold altar in the Jerusalem Temple was, in fact, parallel to a secular vessel that was used in the king’s residence to freshen its air. Some excavated altars, as we have noted, were indeed found in cultic rooms. However, others (such as some of the altars from Dan and Megiddo) clearly stood in the open. Still others were placed at or near the entrance to a house (as at Arad, where the altars stood outside of any room). What were these foolish people doing burning rare incense, as costly as gold, in the open air? We are expected to believe not only that a very costly substance brought from distant Arabia was burned on these altars, but that frequently the incense was burned outside, thus letting it go to waste.

If these altars were not used for incense, what was their purpose? Surely they are altars—at least the ones with horns, an identifying mark of altars. They are too small to be used for animal sacrifice. So how were they used?

The answer is simple: for the cheapest and most unpretentious sort of offerings, that is, the grain-offering (menahot; singular, minhah).

Sacrifices in the biblical world were divided into three main categories: offerings of meat, taken from cattle or flocks; offerings of liquids, that is, libations, mostly of wine; and offerings of grain, that is, the menahot, taken from wheat or barley. These three groups correspond to the three basic components of the (royal) diet in biblical times—meat, wine and bread. The offerings were primarily conceived as the “nourishment” of the gods, as “God’s food” (Leviticus 3:11; 21:21–22; Numbers 28:2).

Meat offerings were sacrificed on large altars, sometimes referred to as bamot.b For the most part, meat offerings were made on an altar attached to a house of God. Because meat was the most expensive offering, it was usually reserved for pilgrim feasts—the feasts of Mazzot (unleavened bread), Shavuot (Weeks) and Sukkot (Tabernacles). Wine libations often accompanied meat offerings. A minhah, or bread offering in the strict sense of the word, also frequently accompanied meat offerings. With these combinations, the sacrifice would encompass all three components—meat, bread and wine (see Numbers 15:1–13; compare, e.g., 1 Samuel 1:24; 10:3).

Fruit was never offered on an altar in Israel, and probably not in its vicinity, such as the Philistine lowlands.8 Birds were practically treated as whole-offerings (see Leviticus 1:14–17; 5:7–10), that is, the whole of the offering was burned in the fire.

The burning of incense, though not a food, was nevertheless one of the “needs” of the stately, royal cult. But both sacrificing birds and burning incense had limited diffusion. In Israel they actually were features peculiar to the Royal Temple of Jerusalem—birds because of their rareness and absence from regular diet and incense due to its high cost.

The grain-offering, minhah, could be offered independently even in the complex sacrificial system practiced in the Jerusalem Temple, and even more readily on the small altars outside Jerusalem. Independent grain-offering might suffice when a more expensive sacrifice was beyond the worshiper’s means (compare Leviticus 5:1–13) or when the simple, inexpensive grain-offering was prescribed from the very beginning (compare Numbers 5:15–26). In addition, anyone could content himself with a grain-offering if he brought it of his own free will, without being called on to do so by circumstances (see Isaiah 66:20; Malachi 2:12–12, 3:3–4).

Grain-offerings were by no means confined to Israel. It is likely that the offerings made on many altars we have been examining were made to a pagan deity, not only at non-Israelite sites such as Philistine Ekron, but, as we shall see, at Israelite sites as well.

Offering grain and pouring libations are typical acts in the worship of a goddess named in the Bible “the Queen of Heaven.” Worship of the Queen of Heaven had branched off from an astral cult (the worship of “the Host of Heaven”) and originated in Assyria. This worship is described in two passages in Jeremiah: “In the towns of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem…the children gather sticks, the fathers kindle the fire and the mothers knead dough, to make kawwanim (certain sacrificial cakes—see below) for the Queen of Heaven, and they pour out libations to other gods” (Jeremiah 7:17–18; see also Jeremiah 44:14–25). These sacrifices burned in fire were explicitly of dough, that is, grain-offerings.

After the Babylonian destruction of the Temple (in 586 B.C.E.), the Jews went into exile, to Babylonia and also to Egypt. The prophet Jeremiah, who went to Egypt, castigates the people there for continuing to worship the Queen of Heaven. A group of men and women challenge the prophet, saying that after they “stopped burning (grain-) offerings to the Queen of Heaven and pouring out libations to her” (Jeremiah 44:18), they were struck by disaster. Jeremiah answers that God has not forgotten what they did “in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem” (Jeremiah 44:21).

The Hebrew verb qatter—which I have translated as “burning (grain-) offerings”—was formerly translated as “burning incense.” The latter translation was quite crucial for our understanding of the use of incense in the ancient Israelite cult. In more recent translations this verb is rendered as “burning sacrifices” (see, e.g., New English Bible, Revised English Bible) or “making offerings” (New Revised Standard Version, New Jewish Publication Society). Yet the clear reference to “kneading dough” in Jeremiah 7:18 testifies that here (and, by inference, in other cases where the verb qatter is used), not just an “offering” was burned in fire, but specifically a “grain-offering.”9 A little frankincense may have been added to the cakes’ dough for a more delicate aroma (hence the use of the verb qatter, a derivative of qetoret, “incense”), but it remained essentially a grain-offering. A little franincense may have been added to the cakes’ dough for a more delicate aroma (hence the use of the verb qatter, a derivative of qetoret, “incense”).but it remained essentially a grain-offering. Judging from both literary and archaeological evidence, however, the grain (or cakes) would not always, or necessarily, be burned in fire. It could also be left lying in place.

The Queen of Heaven is probably equivalent to the Assyrian goddess Ishtar, called sharrat shame “the Queen of Heaven” in Assyrian texts. Some scholars think that in Palestine this name was given to the Canaanite counterpart of Ishtar, Astarte, whose figurines abound in Israelite excavation layers. The Hebrew word for the sacrificial cake offered to the Queen of Heaven, kawwan, is borrowed from Akkadian (that is, Assyrian) kamanu. It was a sweet cake baked with honey or dates and used for cult purposes.10 An Assyrian origin for the worship of the Queen of Heaven is also indicated by its appearance in Judah precisely at the time of Assyrian hegemony, in the reign of Manasseh, that is, in the first half of the seventh century B.C.E. (compare Zephaniah 1:5; Jeremiah 8:2).11

In the first half of the seventh century B.C.E., we are told, the Judahite king Manasseh erected special altars for the “Host of Heaven” in the two courts of the Temple in Jerusalem (2 Kings 21:3–5). Since the text speaks of several altars, rather than just one, we can assume that none of them was very large. We may reasonably suppose that the altars erected by Manasseh resembled in shape those uncovered in archaeological excavations.

Based on this evidence, it appears that most of these altars were used for worshiping the Host of Heaven or the Queen of Heaven. This conclusion is also supported by the fact that the one altar of this sort found outside Palestine comes from Nineveh in Assyria. Indeed, most of these altars date from the period of Assyrian rule in Palestine. At Ekron, where the largest assemblage was found, all the altars (with one exception, which was not in situ) suddenly appear in a single chronological cluster—in the seventh century B.C.E.

By contrast, the assumption that these relatively small altars were incense altars has its only support in the Tabernacle cycle in the Bible, which speaks of an altar of incense (Exodus 30:27, 31:8, 35:15, 37:25), which, in turn, is a projection of the altar in the Solomonic Temple. This one was indeed an altar used for burning incense. But that does not mean that all altars of this form served for incense-burning. Certainly that is the case with regard to altars found far away from the Jerusalem Temple and, in many cases, apart from any cultic building whatever. Indeed, the first mention of the Tabernacle altar (Exodus 30:1) reads: “You shall make an altar” (mizbeah in the absolute state). Then the text adds, “miqtar qetoret,” that is, “an altar of a place for burning, incense,” as if the purpose of the altar is not self-evident and must be specified.12

In sum, when found outside of the Royal Temple, the altars were not intended for incense at all. They were meant for a simple, inexpensive offering—probably a grain-offering. In a special historical context and within special historical limits, this offering was most probably directed to the Queen of Heaven.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Many scholars believe the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, consists of four major strands composed by different authors. These authors are referred to as P (the priestly source), J (from the German term for the Yahwist), E (for Elohist) and D (for the Deuteronomist).

See Beth Nakhai, “What’s a Bamah? How Sacred Space Functioned in Ancient Israel,” BAR 20:03.

Endnotes

In the northern part of Room 244, archaeologists uncovered a square structure measuring about 1 meter by 1 meter and standing 0.27 meters high (about 39 inches by 39 inches by 11 inches) consisting of five horizontal blocks, in the center of which an additional, flat, basalt stone was lying. On the surface of this structure were traces of fire, and the excavators tried to define it, with some hesitation, as an incense altar. See Avraham Biran, “The Dancer from Dan, the Empty Tomb and the Altar Room,” Israel Exploration Journal 36 (1986), pp. 181–183. Seymour Gitin, “Incense Altars From Ekron, Israel and Judah,” Eretz-Israel 20 (1989), pp. 52–57 and n. 2 (pp. 64–65), did not include it in his list and rightly so. Close to that structure were uncovered two jars, sunk in the ground and containing ashes, which probably are of burned bones (Biran, “The Dancer from Dan,” pp. 183–187). The strange structure and the two jars still need an explanation. However, the two altars mentioned above were found at the opposite end of the room, near its southern wall, and certainly have nothing to do with the ashes.

See Kjeld Nielsen, “Ancient Aromas,” BR, 07:03. See also Gus W. van Beek, “Frankincense and Myrrh,” Biblical Archaeologist 33 (1960), pp. 70–95; M. Elath, Economic Relations in the Lands of the Bible (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1977), pp. 99–102 (in Hebrew); K. Nielsen, “Incense in Ancient Israel,” Supplements to Vetus Testamentum Pseudepigrapha 38, (Leiden: 1986), pp. 16–18.

See Gitin, “Incense Altars from Ekron,” p. 60. It should be emphasized that we speak here of the conditions that prevailed in the pre-Hellenistic period. When the standard of living rose, incense became more accessible. In the Hellenistic period, meat consumption also became more widespread.

On the components of the ancient Israelite diet, in which fruit was scanty and usually cooked before consumption, see my remarks in Encyclopedia Miqra’it 4, pp. 543–553 (in Hebrew). There I also pointed out that in biblical times, simple folk, as opposed to the royal circle, were exceedingly modest in consuming meat (pp. 548–553). In fact, they ate meat only during high festivities and pilgrim feasts.

For the meaning of the verb qtr in the piel conjugation, see my Temples and Temple-Service, pp. 233–234.

See Wolfram von Soden, Akkadisches Handworterbuch, p. 430a; Chicago Assyrian Dictionary 8, pp. 110b–111a.

Deuteronomy, in which this worship is mentioned (4:19, 17:3), is also dated by scholarly consensus to that period. See also 2 Kings 17:16, 23:5; Jeremiah 19:13, et al. (passages of Deuteronomistic redaction).