An Alphabet from the Days of the Judges

023

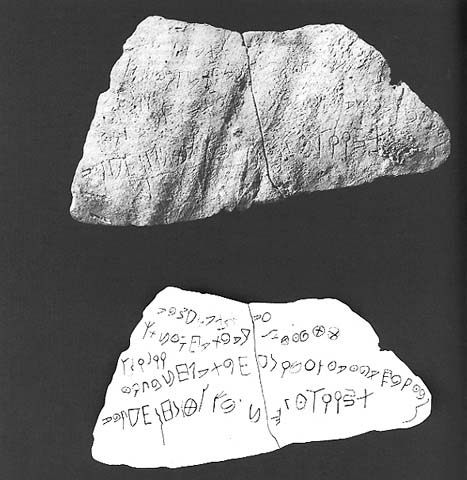

At a site called Izbet Sartah, now believed by some scholars, to be Biblical Ebenezer, a recent excavation by Tel Aviv and Bar-Ilan Universities has uncovered a small clay potsherd—unrelated to the Biblical story—which, however, is the most important single find of the excavation. The sherd contains the longest proto-Canaanite inscription ever discovered.a

The unimpressive looking sherd measures only 3 ½ by 6 inches, but it contains a dramatic addition to the study of ancient Hebrew epigraphy and to the early history of the alphabet.

Inscribed on the sherd are five lines of letters. Most of the letters on the first four lines have been identified, but make no sense as words. We suspect that they are random exercises in writing letters by a student scribe.

The fifth line is, with minor deviations, the Hebrew alphabet, consisting of 22 letters! Unlike modern Hebrew, which is written from right to left, this alphabet was written from left to right (like English). At the time it was written, the writing direction had not yet been fixed.

024

Two kinds of evidence ordinarily enable scholars to date ancient writings, and both are involved in dating the Izbet Sartah sherd: first, the archaeological evidence; that is, what is the date of the archaeological stratum in which the inscription was found? Second, the evidence of the letters themselves—their shape, direction and form. The first type of evidence entails a stratigraphic analysis; the second, a palaeographic analysis.

In the case of the Izbet Sartah sherd, the archaeological evidence tells us in general that the inscription comes from the time of the Judges, between 1200–1000 B.C.b But because of the context in which this sherd was found, it is difficult to be certain of a more exact date on the basis of archaeological evidence. Let us explain why. A typical, even ubiquitous, feature of early Israelite settlements are round storage silos or pits. Grain, jars of olive oil, and other foods were stored in these pits. Sometimes these storage pits are as much as 20 feet deep. At Izbet Sartah, the storage pits are quite shallow because of the thin soil layer: a few inches below the surface, rock is reached. As a result, there are many more storage pits at Izbet Sartah than we customarily find at early Israelite settlements. In the field drawing of the plan of a four-room house, each of the circles represents one of these shallow storage pits. In the vicinity of this house, we found 21 storage pits.

Some of the storage pits are attached to the house. These pits can be related to the various strata of the house; that is, these pits are stratigraphically related to the house and can therefore be dated more exactly.

Unfortunately, the Izbet Sartah sherd was found in Pit 605, which is unattached to the house. Therefore, we cannot be sure in which phase of the house the silo was used, and its contents cannot be dated stratigraphically.

However, based on the shape and form of the letters—by comparing them with other letters on other inscriptions which have been reliably dated and by fitting the letters into a developmental sequence—we can date the Izbet Sartah sherd more precisely—to about 1200 B.C., the beginning of the period of the Judges, shortly after the Israelite settlement in Canaan. This dating is confirmed by the fact that the writing is horizontal and in the left-right direction. (Later, the left-right direction disappeared both in Israel and in Phoenicia, but it reappeared in Greece and the West. Thus, we who use the Latin alphabet, write from left to right today.)

Evidence for Israelites

Another question which arises is how we know the Izbet Sartah sherd is an Israelite, and therefore Hebrew, inscription. We believe that Izbet Sartah is an Israelite settlement. Geographically, the settlement is in the area settled by the Israelites (see “An Israelite Village from the Days of the Judges,” BAR 04:03). A comparison of the rather rude material culture of Izbet Sartah with the sophisticated Philistine material culture at Aphek also suggests that the former was Israelite. In addition, we found typical Israelite storage pits in abundance. Finally, the four-room house which we excavated is a unique architectural contribution of early Israelite settlements. In the house in the plan we find a broad (but relatively narrow) room and three long (but relatively narrow) rooms extending from the broad room, so that the house forms a rectangle like this:

The middle long room was probably an unroofed court in which the cooking was done. This architecture also suggests that the village was Israelite. Together, all these factors leave little doubt that Izbet Sartah was an Israelite town. A peculiar letter order in the alphabetic inscription also indicates that the sherd was written by an Israelite.

The Izbet Sartah sherd was almost missed. It was saved from the discard heap by an alert Tel Aviv University student named Aryeh Bornstein, who thought he saw writing on the sherd. But it was so faint that others refused to believe him. The letters became clearly visible, however, when (following the 025suggestion of Professor David Owen of Cornell University, an Assyriologist who has worked with ancient cuneiform texts) we applied an ammonia solution to the sherd. To appreciate how faint the writing was—to the point even now of being semi-illegible—consider that the width and depth of the incisions do not exceed 1/10 of a millimeter.

However, by careful study we have been able to discern at least 85 letters on the sherd. The importance of this contribution to early epigraphy is emphasized by the fact that this sherd is the longest inscription in the so-called proto-Canaanite script available from the 12th century.

The first four lines of the Izbet Sartah inscription are much shallower than the fifth line, which suggests that one scribe wrote the first four lines and another the fifth. Probably the first four lines were added after the fifth by a student who was less artful than the one who wrote the fifth line. However, the first four lines, like the fifth, are written from left to right, as we know from the fact that the letters face right.

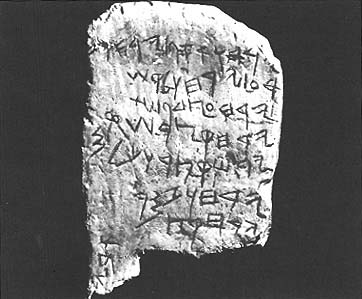

The alphabet in the fifth line is known to scholars as an abecedary. Although partial abecedaries have been found in a number of excavations, complete abecedaries in Phoenician, Hebrew and Aramaic are very rare. The Izbet Sartah sherd’s 12th century date makes it the oldest Hebrew abecedary yet discovered from the Iron Age. It is also the most complete; it is missing only the letter mem (m), though a line or two of the letter may be discerned. It is 400 years older than the next oldest Hebrew abecedary, a five letter graffito found about 1935 by J. L. Starkey incised on the step of the palace at Lachish. The Izbet Sartah abecedary is about 200 years older than the famous Gezer calendar, a 10th century school child’s mnemonic ditty about the agricultural seasons, which, prior to the discovery of the Izbet Sartah inscription, was considered the earliest Hebrew inscription of any significant length.c

028

Literacy in the Bible

The Bible contains a number of tantalizing references to early writing and Israelite literacy. Naturally, the question arises as to whether these references are anachronistic—written at a later time and describing a later practice which was incorrectly projected backward to an earlier time—or whether these Biblical passages accurately reflect contemporaneous conditions.

For example, after the conquest and settlement of five of the tribes, Joshua gathered representatives of the remaining seven at Shiloh and commanded them: “And you shall describe the land in seven divisions and bring the description here to me … ” (Joshua 18:6). These tribal officials wrote lists of the cities (Joshua 18:9) which were to become part of their territories. Whatever the period of the final redaction of the chapters of Joshua describing the division of the land (Joshua 15–19) and their incorporation into the Book of Joshua, it is now quite clear from the discovery of the Izbet Sartah sherd that there was some degree of literacy among the ancient Israelites.

The Song of Deborah (Judges 5) is almost universally attributed to the period it describes (12th century B.C.). This ancient poem states that some of the tribal leaders were literate. Deborah describes the mustering of her forces: “ … from Machir the commanders marched down and from Zebulun the bearers of the scribes’d staff [marched down]” (Judges 5:14).

The most frequently quoted passage used as evidence for widespread popular literacy is Judges 8:14: “And [Gideon] caught a young man [na’ar] of Succoth, and questioned him; and [the young man] wrote down for [Gideon] the officials and elders of Succoth, seventy-seven men.”

This verse has often been taken to imply popular literacy, as if the young man Gideon questioned was just an ordinary student who happened to be passing by. In fact, the na’ar is not an ordinary boy returning from his lessons who could, upon request, recall the names of the many town elders; he is an official of the local municipality whose duties demanded a familiarity with lists of the local aristocracy who were taxpayers and members of municipal oligarchy. Translating na’ar as young man is misleading in this passage. Recently discovered seals indicate that a na’ar was also an official position, a kind of attendant or steward of a large estate, royal, municipal, or (possibly) private. In a military context, na’ar may be translated as attendant, squire or armour-bearer (see N. Avigad, “New Light on Na’ar Seals” in Frank Cross, et al, ed. Magnalia Dei, 1976). Moreover, Succoth was probably a Canaanite enclave, which means that this official was not an Israelite at all. However, the Israelites probably learned from the Canaanites and developed their own scribal schools for administrative purposes. The scribes at Izbet Sartah may have been part of this tribal administration.

Thus, although the Izbet Sartah sherd does not indicate how widespread popular literacy was in the day of the Judges, it does substantiate the fact that writing was a medium already adopted by the Israelite tribes for administrative purposes.

Earliest Alphabets

There is, however, another reason to believe that the ability to read and write was more widespread in Palestine than elsewhere in the Middle East. That is because it is so much easier to read and write with the use of an alphabet than with the extraordinarily complex, multi-sign system commonly used for writing in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Mesopotamian cuneiform. Frank Moore Cross Jr. has said that “The invention of 029the alphabetic principle put literacy in the reach of every man, permitting the democratization of higher culture.” (Eretz-Israel, Vol. 8:8–24 (1967))

The hieroglyphic system has hundreds of different signs. Similarly, cuneiform systems commonly require the use of hundreds of signs representing a variety of syllables and non-phonetic elements.e With the exception of the cuneiform system developed in Ugarit, in the 14th century, no cuneiform system of writing ever developed into an alphabet (the Ugaritic exception very probably occurred when the Ugaritic people adapted their cuneiform signs to the alphabetic concept already developed in Canaan).

The alphabet—originally consisting of 22–30 signs—appears to have been invented by Semites in Canaan sometime between the 18th and 16th centuries B.C. At least these are the earliest examples of alphabetic signs which have been uncovered thus far.

The Izbet Sartah sherd is evidence of the presence of Israelite alphabetic exercises even in this small outpost on the Philistine border at a time when the Israelites were just beginning to settle the land.

Ultimately, the Canaanite alphabet spread throughout the world. The Greeks adapted that alphabet to their own language and from there it spread to the West.

The Izbet Sartah inscription also sheds unexpected light on the vexed question of how old the Greek alphabet is. The Greeks devised the letters of their alphabet from a Semitic prototype. The question is when?

Most modern scholars of ancient Greek scripts have followed Rhys Carpenter who in the 1930’s argued that the Greeks developed their alphabet during the 8th century B.C. His argument was based on the similarity of Greek and Semitic letters in the 8th century and also on the absence of any earlier Greek texts.

Recently, however, Joseph Naveh of the Hebrew University has argued that the Greek borrowing of the alphabet occurred as early as 1100 B.C., despite the absence of Greek epigraphic evidence at such an early period. Naveh bases his argument on two points. First, 8th century Greek inscriptions are written left-to-right, right-to-left, and boustrophedon (back and forth, as the ox plows). This is also true of proto-Canaanite inscriptions from the Late Bronze Age, 17th–12th centuries B.C., but is not true of later Phoenician inscriptions which were once thought to provide the example for the Greek adoption of the Semitic alphabet. These later Phoenician inscriptions (10th to 8th centuries B.C.) are all written from right to left. Therefore, argues Naveh, if the Greeks had borrowed the Semitic alphabet from later Phoenician inscriptions, the Greek inscription would have been written right-to-left, not in the variety of directions characteristic of earlier Semitic inscriptions.

Naveh’s principal argument, however, is based on the shape of the Greek letters. He convincingly argues that the Greek letter shapes of the 8th century far more closely resemble the proto-Canaanite letters of the Late Bronze Age than letter shapes (including Phoenician letters) as they had developed by the 8th century. Thus, he concludes that the Greek borrowing occurred during the earlier period.

The major stumbling block to Naveh’s argument has been the absence of a long-legged kaf in the proto-Canaanite alphabet which could serve as an example for the Greek kappa. If there was no long-legged Semitic kaf at this early period (when Naveh contends the borrowing took place), the Greeks could not have borrowed their kappa at this early period. And if not kappa, perhaps not the rest of the letters. The 12th century Izbet Sartah sherd, however, contains welcome confirmation for Naveh’s thesis. The Izbet Sartah sherd contains two forms of the kaf. Each has a long leg, a suitable prototype for the Greek kappa! Thus the Izbet Sartah sherd provides important evidence for the very early diffusion of the alphabet 030and significantly strengthens Naveh’s thesis that the Greeks borrowed the Semitic alphabet in about 1100 B.C.

In addition, the earliest Greek letters from the 8th century are closer to other letters in the 12th century Izbet Sartah sherd (alef, dalet, he, het, yod, nun, ayin and shin) than the early Greek letters are to Phoenician letters of the 10th–8th century B.C. This too suggests that the Greek borrowing occurred earlier—from Canaan rather than from Phoenicia as so long supposed.

These are exciting developments in the history of the alphabet. This modest sherd from an Israelite village has made an unusual contribution to our understanding of this history.

Acrostic Puzzle Solved

The Izbet Sartah Sherd helps solve one final alphabetic puzzle. The alphabet is frequently used in the Bible as a poetic guide. The Bible contains numerous alphabetic acrostics: The first letter of each line of these poems forms the alphabet. Many psalms are alphabetic acrostics (Psalms 9, Psalms 10 [Psalm 9 contains the first half of the alphabet and the reconstructed Psalm 10, the second half], Psalms 25, Psalms 34, Psalms 37, Psalms 111, Psalms 112, Psalms 119, Psalms 145). The Book of Proverbs ends with a famous acrostic poem, a paeon to the “Woman of Valor”, which is frequently recited in Jewish homes by the husband to his wife on Sabbath evening (Proverbs 31:10–31). The prophet Nahum opens his book with a partial alphabetic acrostic.

The first four chapters of Lamentations are alphabetic acrostics, the third chapter repeating each letter three times. There is a peculiarity in the letter order, however, in Chapters 2, 3 and 4 of Lamentations. Instead of the usual order of the letters, two letters are reversed. Instead of the order ayin-pe, we find pe-ayinf. This reversal has long puzzled scholars.

A peculiarity of the Izbet Sartah abecedary is that it too contains the pe-ayin letter order. It thus verifies a local scribal tradition in which this was once the order of the letters. Another Hebrew abecedary recently found by Ze’er Meshel at Kuntillat Ajrud, an Israelite fortress in the Sinai dating from the late 9th or early 8th century B.C., also contains the pe-ayin sequence. Hence it appears that this local Israelite variation in letter order was used from the time of the Judges at least through the Israelite monarchy and probably through the Exilic Period when the Book of Lamentations was written.

(For further details, see A. Demsky, “A Proto-Canaanite Abecedary Dating From The Period Of The Judges And Its Implications For The History Of The Alphabet.” Tel Aviv, Vol. IV, p. 14 (1977)).

At a site called Izbet Sartah, now believed by some scholars, to be Biblical Ebenezer, a recent excavation by Tel Aviv and Bar-Ilan Universities has uncovered a small clay potsherd—unrelated to the Biblical story—which, however, is the most important single find of the excavation. The sherd contains the longest proto-Canaanite inscription ever discovered.a The unimpressive looking sherd measures only 3 ½ by 6 inches, but it contains a dramatic addition to the study of ancient Hebrew epigraphy and to the early history of the alphabet. Inscribed on the sherd are five lines of letters. Most of the letters on […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Proto-Canaanite is the name scholars give to the oldest known alphabet. Presumably many Semitic languages, including Hebrew, were written in this alphabet.

Three occupational strata were found at Izbet Sartah. The earliest, Stratum III, dates from the 12th century. Stratum II from later in the 12th century revealed the most important occupation. The Stratum II village was abandoned after the battle of Aphek-Ebenezer in about 1050 B.C. The site was unoccupied until about 1000 B.C. when it was very briefly resettled, as revealed in Stratum I. Then Izbet Sartah was abandoned forever.

The text of the Gezer Calendar is as follows: (as translated by W. F. Albright Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), p. 320)

His two months are (olive) harvest,

His two months are planting (grain),

His two months are late planting;

His month is hoeing up of flax,

His month is harvest of barley,

His month is harvest and feasting;

His two months are vine-tending,

His month is summer fruit.

It was found by R. A. S. Macalister during his extensive Gezer excavations between 1902 and 1909.

The Hebrew word here translated “scribe” is sopher, the first time it appears in the Bible. Some scholars have deleted it from their reconstruction of the original poem, others have translated it “official.”

Cuneiform denotes writing systems which use wedge-shaped signs made by pressing a stylus into soft clay tablets.