040

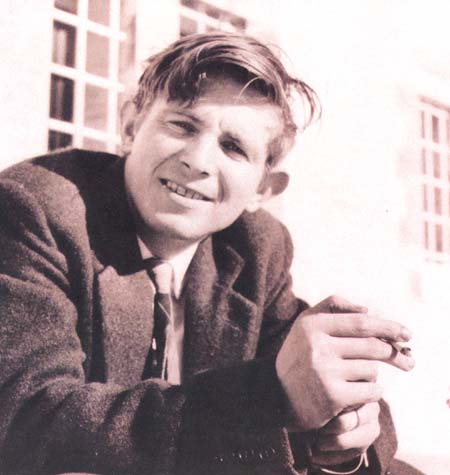

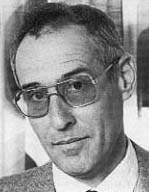

Harvard professor John Strugnell was chief editor of the official Dead Sea Scroll editorial team from 1987 until he was dismissed in late 1990, after giving an anti-Semitic interview to Israeli journalist Avi Katzman, in Ha’aretz, November 9, 1990, and “Chief Dead Sea Scroll Editor Denounces Judaism, Israel; Claims He’s Seen Four More Scrolls Found by Bedouin,” BAR 17:01. An original member of the editorial team, Strugnell had been studying the scrolls for over 40 years and was one of the most significant players in the Dead Sea Scroll drama. A brilliant, complex man, he has dropped from public sight since his dismissal.

Today, on medical leave from Harvard, he is nevertheless back at work on several Dead Sea Scroll texts. He is also writing his memoirs.

Despite the fact that BAR was critical of him when he led the official DSS editorial team, he readily agreed to a BAR interview. He also offered us a chapter of his memoirs—his renvoi to Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin, which we print in “Yigael Yadin: ‘Hoarder and Monopolist.’”

Although, needless to say, we do not agree with all of his views, we do believe that Professor Strugnell deserves a forum to speak in his own words.

Professor Strugnell opened the interview himself without waiting for a question:

John Strugnell: I would prefer that this interview come out in BAR rather than Bible Review. Also I think it would not be useful to spend time going over the interview that was the subject of public interest about three years ago. That was given at a time when I was manic-depressive and goodness knows what else. I think that disqualifies that interview from forming a serious basis for our discussion.

041

Hershel Shanks: It’s your prerogative to say that you prefer not to answer anything that I ask or to discuss any subject that you don’t want to discuss. But that interview, in a sense, did you in, and has affected the way the public sees you. So I wonder if it might not be in your interest, if, as you’ve just said, you were manic-depressive at the time …

JS: And I stayed manic-depressive all the time up to my being dismissed [as chief editor of the Dead Sea Scrolls publication project] and up to considerably later than that. You know, I’m still under medical supervision for manic depression. I am not completely free of it yet.

HS: I hope that you’re making progress and will be free of it soon.

JS: At the very beginning of the interview [with Israeli journalist Avi Katzman] I said, I do not want my critical statements to be viewed as anti-Semitic. They’re not. Mr. Katzman straight away went and interpreted them and discussed them as anti-Semitic. I suspected behind Mr. Katzman a worry whether Christian scholarship could deal impartially with the nature of the scrolls, being documents of a Jewish sect. I wanted to say, “Nonsense, there’s no difficulty here. It is in the nature of exegesis to be able to understand impartially documents from groups other than your own.” Actually, Jewish scholars would be even more disqualified to work without bias on the scrolls than Christian scholars. It wasn’t the Christians who were the principal enemies of the Dead Sea Scroll sect. It was the ancestors of Phariseeism. I’m amused when I hear people like [Lawrence] Schiffman [of New York University] saying how sad it is that Jewish scholars have not been working on these texts. In a sense, Jewish scholars 042would be the ones most likely to express an exegesis that is hostile to the thought of the Qumran sect, more so than Christian scholarship. [The essential thing is that one should be aware of one’s own biases, whether Jew or Christian.]a

HS: But it is true that as a result of that interview, you have been branded an anti-Semite. You said things in that interview, like calling Judaism “a horrible religion” …

JS: Yes.

HS: … like saying that the answer to the Jewish problem is mass conversion to Christianity, like saying that Christianity should have been able to convert the Jews, like saying that Judaism was originally racist. Those things have been interpreted, and understandably so, I think, to characterize you as an anti-Semite. After that was published, about 70 of your former students signed a letter in your support, which we printed in BAR [BAR 17:02], and they were careful to distance themselves from what you said. I believe they characterized what you said as the result of your …

JS: Wasn’t it sickness or something?

HS: Yes, but they made it clear that they didn’t agree with what you said.

JS: Yes, they explained it as sickness.

HS: Is that your explanation, too? Just a moment ago, I didn’t think you were explaining it on the ground of sickness.

JS: Now we’re getting dangerously near the point where I stop answering these things. I’m willing to discuss what I might have been thinking of, but I am not willing to discuss the framework in which I’m thinking of these matters. I agree that these [words] caused great troubles for me. They’ve since pained a lot of my friends and alienated them from me, and this has grieved me greatly. All that is true. But I’m not willing simply to abandon my views, even to the point of just saying all right, I was wrong, what should I substitute for it. [That’s not how we deal with a religious dilemma.]

HS: You characterized yourself in that interview as an anti-Judaist. Do you stick by that?

JS: It is a tricky word. What is an anti-Judaist? Is he a person opposed to Jews, or is he a person opposed to Judaism? I am opposed to Judaism [on purely theological grounds].

HS: Why?

JS: Obviously that is asking me to get into the whole matter of the traditional Christian teaching, and that’s where I took my stand.

HS: And that’s where you stand today, too?

JS: That’s where I basically am today. You know, the Catholic Church is changing. They’re teetering between changing and not changing. But basically I take my stand on the stance of the New Testament on this question.

HS: Which is?

JS: At various places in the New Testament you get varying positions about the total conversion [or future] of all the Jews. A lot of people talk about how my position is supersessionist. I have a much more positive viewpoint. I’m looking for a largeness in Christology, I’m looking for making higher claims for Christ [and the consequences of these for the Jews].

HS: What are those higher claims?

JS: [They vary.] You can look at them in Matthew. You can look in Mark. You can look in Luke. You can look in the beginning of John, especially in the beginning of John. You can find them in Paul, you can find them in some of the earliest pre-Pauline fragments, talking about how every knee should bend and confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, and so on. Wherever I look, I find a higher Christology. This becomes for me canonical, the canon of what I should believe. But these are things that I really don’t want to discuss. I’ve gone further than I had intended to, but I wanted to show you that my intention is to find positive and larger, higher Christology. You know, it’s funny that a person is under so much attack for his Christology. I understand that letter [from 70 of my former students], how shall I put it, represented a consensus position. Some of them wanted to say “Never,” some of them wanted to say “Practically never,” [laughs] and some of them …

HS: “Never” and “Practically never” what?

JS: They never heard me take an anti-Semitic position. So it was a consensus letter—everyone could sign, but some with greater enthusiasm than others. Still I appreciate very much their kindness in coming to my aid at a time when I needed it.

I don’t think that at any time when I was editing the scrolls, or especially at any time when I was the chief editor of the scrolls, I don’t think I thought of these matters. I brought in Jewish scholars. I brought them in before I was chief editor. I never used that as a criterion. I didn’t ask them what sort of Judaism they practiced or anything like that. I brought in [Elisha] Qimron, for instance, because he knew middle Hebrew so well. I brought in Devorah Dimant because she seemed to be the most gifted among the younger Israelis in reconstructing a literary document. I brought in Joe Baumgarten. I can’t claim any particular virtue for choosing the Jewish scholars that I brought in, except that I chose them as the most qualified scholars living around Jerusalem or able to come and help in the work. I discover by surprise that I have become also the great Liberator of women in bringing women into the project. Some day someone will put up a statue in my honor in this regard. But there again, I didn’t go out to find women and to bring them into the project. They were the ones who were available and who were showing competence in this field.

HS: But I take it from what you say, you have nothing to retract or apologize for in the Katzman interview.

JS: No, that’s not so, because I say that I would not have said it in that way, I would not have said it that way if I had not been under manic depression, probably also under alcoholism, at least a certain amount of alcoholism, but probably too much. [But for that] I would have walked far more carefully. [I should have kept to the effects of Judaism or Christianity on each editor’s work.] That’s how I’m trying to do in this interview.

043

HS: What’s coming through to me as I listen to you is that what you’re saying is that you’re really anti-Semitic, or anti-Judaist, as you call it, but if you had not been manic-depressive and if you had not been alcoholic at the time, you might have expressed yourself more sensitively, more delicately, but still your views are anti-Judaist and what the world calls anti-Semitic. You are regarded as an anti-Semite and you’ve never retracted, you have never apologized, you’ve never been very specific as to what you said that you shouldn’t have said and that you don’t believe. On the contrary, you seem to be affirming it right now.

JS: [If you are unwilling to make the distinction I try to make, between opposition to a viewpoint and a group, etc., etc., you disqualify yourself from discussing my views.] If you notice the question that was asked by Mr. Katzman, he was asking a question about the group of Qumran editors. I was trying not to give an answer about what I was thinking, but to give an answer that would liberate the editorial group from the charge of being incompetent, of showing bias in the editing of the scrolls. To find something that [Frank M.] Cross and I and [J.T.] Milik and [Emile] Puech would agree to is an impossibility. So I tried to sail right through. I took refuge behind the traditional position of Christianity.

HS: What is the traditional position of Christianity?

JS: It’s not essentially what people call supersessionism. It is maximalistic Christology. It is claiming the most for the rights of the Messiah, claiming the most rights for Jesus, to put it in a nice simple framework that your Southern Baptist readers will appreciate.

HS: What does being anti-Judaist mean?

JS: It means, probably, being against the religion of Judaism. It’s not being against individual Jews or the Jewish people. The Cardinal Archbishop of Paris is a Jew and he gets on perfectly well with his archdiocese, which is not Jewish.

HS: What you’re saying is you don’t like the religion of Judaism, but you don’t mind Jews?

JS: Yes, yes, that’s one thing. But I’m not really concerned whether I dislike or like the religion of Judaism. I want more things for the religion of Christians. I want the reign of Christ to be more glorious, which it would be certainly by having 20 million more Jews on board.

HS: As Christians?

JS: Yes, yes. That, to me, is a description of the traditional view of the Christians. There have been attempts to interpret modern synodical doctrines [Vatican II] as meaning something very different from this. There are other people who are trying to interpret the synodical statements in a minimalist way.

We are in the early stage of the interpretation of Vatican II. Varying groups are pushing or pulling one way and the other. It’s not yet clear how it’s going to go.

HS: How do you prefer it to go?

JS: Really, I am a humble little editor of Dead Sea Scrolls living in my corner. Not for me these great battles.

HS: In the Katzman interview, you defined anti-Semitic as being against Semites, not against Jews. I think that’s a bit disingenuous. Anti-Semitic really means anti-Jewish. When someone says to you, “Professor Strugnell, are you an anti-Semite?” what is your response?

JS: First of all, I say that I don’t like that word because it’s not precise. If it were to mean against all Semites …

HS: No, it means against all Jews. That’s what it means in the dictionary.

JS: If you want to say, “Are you against Jews?” of course I am not. That is why I say I am an anti-Judaist, but not one who is against individual Jews. [As a matter of fact, the monstrousness of Hitler’s anti-Semitism was the first abomination I became keenly aware of.]

HS: Do you think there is any relationship between being anti-Judaist, that is, being opposed to Judaism as a religion on the one hand, and anti-Semitism?

JS: You see, there clearly have been huge amounts of persecution of Jews, so you have to ask yourself, “Are these persecutions related to the fact that most parts of Europe are also in large measure Christian?” I ask myself, “Is there any relationship?” Yes and no. Take Hitler’s Germany, for instance. The Christians were a principal opposition to Hitler’s Germany. But a lot of so-called Christians got caught up in Hitler’s Germany.

HS: In many people’s minds, the views you hold about the Jewish religion have led to anti-Semitic acts and to anti-Semitism. Do you want to comment on that?

JS: I don’t know anyone who has gone and read my interview in BAR [“Chief Dead Sea Scroll Editor Denounces Judaism, Israel; Claims He’s Seen Four More Scrolls Found by Bedouin,” BAR 17:01] and has then gone out to defile a synagogue just because they read my interview. You can’t say that the interview produced anti-Semitic revulsion and the burning of 044synagogues and the like.

HS: Is that all you have to say?

JS: [My answer was perhaps flippant, but no answer can be given until you are willing to make the distinction I ask for.] My positive statements about a high Christology have nothing to do with individual Jews whom I may happen to like or dislike.

HS: You are aware, are you not, that you are regarded as an anti-Semite?

JS: Well, I am not regarded as an anti-Semite by those who sat through my lectures. I mean, some of them regard me as a little fuddy-duddy in the form of my Christology.

HS: Would it be fair to say that you’re an intellectual anti-Semite?

JS: [Of course not, if you persist in using the term “anti-Semite,” which I have specifically abjured.] I was wondering, yesterday I think it was, what’s wrong with desiring to convert another group of 045people to your own religion, [of course without force, ] to your own style of life? In philosophy [and in politics] we do this all the time.

HS: Is this philosophy of yours affected at all by the fact that for the last 1,500 or 2,000 years the views that you have been espousing have resulted in the oppression and even murder of millions of Jews? Does that have any effect on your thinking?

JS: Whew! [sighs]

Does the fact that Judaism has been, as it were, the lower person on the totem pole for the last 1,500 years have any influence on my view? I don’t think so. [In any case, the role played by Christian theology, as compared with other causes, requires precise analyses and distinctions that you are not letting me make.]

HS: Do your Jewish students find offensive the views that you hold?

JS: No. [laughs] You must remember that I hardly ever discuss this in class, so they wouldn’t have had much chance.

HS: How do you think that the [Dead Sea Scrolls editorial] project is being run today?

JS: I really don’t want to criticize it. When I have things to criticize, I talk to [Emanuel] Tov [the new editor-in-chief].

HS: At one time you claimed, according to the Associated Press, that the Israelis were trying to take credit for research that your team had done. According to the Associated Press report, “Strugnell said he would fight Tov’s appointment, which he called ‘an alarming attempt by Israeli scholars to claim credit for the research.’”

I heard that at one time there were shouting matches between you and [Amir] Drori [Director of the Israel Antiquities Authority] and the [Israeli oversight] committee, and threats of lawsuits. Is there anything to that? Were there shouting matches?

JS: I can think of one or two.

HS: Were there threats of suit?

JS: Ah, yes, there could have been. I had an Israeli lawyer. I’m not about to tell you her name. She said, “Well, yes, I could certainly stop them in the court.”

HS: From taking over your powers?

JS: Yes. We were all bad-tempered men then. At one time Drori threatened to have me thrown out of the museum and things like this. But then, these are just the sort of things that go on, that enliven a pleasant discussion.

They wanted to make more delegations of texts. I insisted that we should go at the speed of the editors. I was willing to make sure that people were kept to their targets, chivvied on, but I was not willing to throw them out, or to throw out their work and make it available to the public.

HS: You weren’t willing to make the photographs available to the public.

JS: I wasn’t willing to do that. But I would be chivvying all along. I did get out of Milik a half to a third of his texts distributed without any hard feelings. It was like pulling teeth from a cat.

The Israelis wanted to delegate at a much faster speed. I said, “You cannot take over work that a man has done, which he has been working on for a lifetime, you cannot just walk in and take this over.” I refused to have anything to do with that [—they had after all accepted my initial timetable for publication].

The loss of Milik I consider the most despicable act of the [Israeli] advisory committee. The inactivity of [Frank] Cross [professor emeritus at Harvard] in his defense was a little shameful. Milik was not pushed out. He wasn’t expelled, but he was harassed out.

The Israeli committee consisted of [Shemaryahu] Talmon [of Hebrew University], Jonas Greenfield [of Hebrew University], and [Magen] Broshi [curator of the Shrine of the Book]. I saw them as the two daughters of the leech in the Book of Proverbs. It says there that the leech, the blood-sucking animal, ha-aluqah, has two daughters crying, “Give! Give!”b

HS: Who do you compare these to?

JS: Talmon and Greenfield. They were wanting to have more and more [texts to edit].

HS: For themselves?

JS: Yes, exactly. [And for others.]

HS: And they got it?

JS: They got it. My initial anticipation had been that the committee should have very little authority, but they should be employed precisely because they had done a lot of editing, so they could see where cracks were developing. [sighs] But all that is something that I don’t have to bother myself with now. That’s Tov’s problem.

HS: Are you bitter?

JS: What I’m bitter about is that the whole thing wasn’t done in a gentlemanly fashion. Yes, I would have liked to have … I wouldn’t want to work with the group there now. It leaves too bad a taste.

HS: Why?

JS: Primarily the chasing out of Milik. This man was the founder of the whole project, and has more sensitivity for these materials in one of his fingers than any of that group. So that I can’t forgive. But, you know, I spent a lot of time working on these documents, and I would like to see them well published. So I’m willing to collaborate with Tov, and give him suggestions, and things like this, so he can do his job as best as he can. It’s a strange thing when you ask me if I feel bitter. I am quite happy to collaborate with this one or that one of the younger scholars. They come in and they have bright ideas, and I encourage them. But some of the older ones, they conducted themselves rather cheaply.

My lawyer said that she could hold them in the courts for as long as we wanted … but the relationship between me and the rest of the editorial supervision committee had just become too embittered. The only period when I had any real authority was precisely the period after I was accepted as editor-in-chief; and then came the period when I was fighting cat-and-dogs with them up until the end of 1990.

Did you not have the feeling that they were as adamantly opposed to the distribution of the photographs as I was?

HS: Yes.

JS: It was a strange business. I hope never to be in such an affair again. [Of course, my contributions to our arguments were not improved by my manic depression.]

HS: Your health is okay now?

JS: Fairly. I mean, you know, I’m not teaching anymore.

HS: What is your relationship to Harvard?

JS: I’m on a leave of absence because I’m under the doctor’s care for manic depression.

HS: How long have you been on leave?

JS: About three years.

HS: Is it your intention to go back?

JS: Well, at the moment, I have a very pleasant relationship with Harvard. I don’t have to teach anyone. I can continue working on my Qumran work, and I do this on virtually the same salary I got before.

HS: From Harvard?

JS: Yes. I find this very comfortable. I sometimes ask myself whether I’d like to go back to teaching, but it is very attractive not to teach.

HS: Have you got the alcoholism licked?

JS: For sure.

HS: I don’t know a lot about manic depression, but in the Katzman interview, you apparently phrased things differently 046than you would have had you not been suffering from this ailment. Can we say that today that’s not affecting the way you’re talking?

JS: That’s why I’ve been saying, do not mention some of the topics, because you’re never completely cured from manic depression. I feel in good form today, but to be able to give myself a good mark is often beyond me. I have to be always careful. I’m kept all right because of a large number of pills. I don’t need anything for anti-alcoholism, but I do need, definitely, these anti-manic-depressive pills. And it works.

HS: Well, I don’t know if this is a fair question or not, but, you know, the Katzman interview is on record, so to speak. And one wonders whether as a result of the manic depression, you were unrestrained in what you said, or whether you were saying things that you didn’t believe.

JS: This is really something that you should ask of the doctor. People say with manic depression that you have a poor sense of reality, and maybe that’s the simplest way of phrasing it. Katzman did read the interview to me on the phone. And you’d have thought that I would have recognized that there were troubles with it. But at that time, and when I was back in Cambridge, I didn’t recognize the way in which this would have really such an effect.

HS: There’s this strange story that’s been in the papers, that at one point two prostitutes, one Jewish and one Arab, came to you at the École Biblique [the French School in Jerusalem] and, I believe, took you to a field outside of Bethlehem where they removed from their private parts microfilms of Dead Sea Scrolls, one of them being the complete book of Enoch. Is that true?

JS: [laughs] Well, there are a lot of mixed elements, bits of which are true, but bits of which are false.

HS: Could you tell us the story?

JS: There was a whore. [Removing colorful accretions, there were women messengers of uncertain profession who showed me a microfilm—not at the École Biblique nor even in Jerusalem.] Now the incident in the field outside Bethlehem belongs to a completely different story.

HS: Oh, well, let’s go with the first story about the whores.

JS: No, no. [laughs] Let’s forget them. Let’s go to the field outside Bethlehem. I went to the field outside Bethlehem way back in 1957, when I came back to Jerusalem. I was staying in the British School of Archaeology. Someone came to me.

HS: Who was that?

JS: A dealer in antiquities.

HS: Kando?

JS: No, it was distinctly not Kando.

HS: Ohan?

JS: No, it wasn’t Ohan. Anyhow, this person came to me and he said, would I go on a certain day to see some people in the corner of a field near Bethlehem and look at some antiquities. I didn’t have a car at the time, but I had a friend who was the director of the British School, and he had a Rover. This was Peter Parr. He agreed to drive me. I went with my wife; she was keen to come on a famous little picnic in the country.

We went down to a village near Bethlehem called Artas. In the fields below the convent there were about four or five people sitting lazily on walls round about with their guns. The dealer was there and he introduced me. And I saw one large and one smallish roll of leather. The smallish one contained bits of six or so columns. I recognized the script, but I didn’t recognize the text. The script was a late Herodian script.

The other one was much more tricky because it was very difficult to open. It was decayed on all sides. I told him I’d want to have something like a knife to just open it to see what was there. You know, it could just have been shoe leather. But I didn’t think so. So we made an appointment for two days from thence when I should bring back instruments sufficient to open it up. And then I would be able to tell.

I was later told that Kando had fallen on them and tried to get the scroll into his own hands, and that they were no longer available.

HS: This was after the two days.

JS: Yes.

HS: Who told you that?

JS: This was [Père Roland] de Vaux [then chief editor of the scrolls]. So here then was certainly one small scroll and possibly one very big scroll.

HS: You never did see the script on the big scroll?

JS: No. I saw enough to see that it was probably inscribed. Just towards the edges I got tiny bits of ink, but not enough to get an identification.

HS: So the second meeting never took place?

JS: The second meeting never took place.

HS: You don’t know what the content of the small one was?

JS: The conditions were far from ideal. I could see that it was in Hebrew. The next scrolls that I heard of was when [G. Lankester] Harding [the last British Director of Antiquities in Jordan] was dying in London.

HS: Do you remember when that was?

JS: It was in January of ‘79 or ‘80, I think. I went to visit him and we talked. You know, he wanted to see that his major project, the setting up of the scrolls team, was going along well after the Israeli occupation. So I was able to reassure him. And then I told him that the Israelis had found one large scroll.

HS: The Temple Scroll?

JS: Yes. Then I told him that I had seen at least one other one. He told me that he had been taken to Aleppo in north Syria to see three other scrolls.

HS: Was he clear that they had come from the Qumran area?

JS: Yes. Harding was a good paleographer. He’d started his career at the dig at Lachish, making copies of the Jewish ostraca found at Lachish. He could copy well. He had been around for the discovery of most of the Qumran scrolls. He was a good, careful archaeologist. He probably could have told you if it was Hebrew or Aramaic.

HS: Did he mention the content of any of these three scrolls?

JS: He was not seeing them in the most ideal circumstances. These were just people who presumably thought, here is an official of the British government, maybe they would sell them to London.

HS: Were they dealers?

JS: You know, when I spoke to him, Harding was not in great shape.

HS: He was in bed?

JS: Yes, his deathbed. He was heavily sedated, and only lasted another few days.

HS: Did he tell you when he saw them?

JS: Yes, he did and I am always frustrated about not having made an exact note of this. But I think it was round about 1968, ‘69, after the Six-Day War. These could be the ones that I had said probably were already in Jordan after the Six-Day War onwards; maybe they moved onwards. And then I, myself, saw one—the Enoch microfilm; but I must save that story for my memoirs.

HS: This is the story about the prostitute.

JS: Yes.

So I wouldn’t be surprised if there were five other manuscripts from Cave 11 sometime to be found in the near future. I wouldn’t be overwhelmed if there were seven or eight. If none ever came to light, I would wonder who on earth had been having these hallucinations, or why they 047are being held back.

HS: Are you currently working on trying to purchase or acquire these scrolls?

JS: Yes, we’ve got people interested in it. But after the big upheaval in Kuwait, things settled down, and the urgency of trying to get rid of this material evaporated.

HS: You tried to acquire it during the Kuwait crisis?

JS: That was when it was shown to me.

HS: And how did you communicate with the owner? Did you meet him?

JS: Yes.

HS: In Jerusalem?

JS: No. Now, you see, here we can come to a stopping point.

HS: All right. Don’t answer if you don’t think you should.

JS: I mean, it’s unnecessary.

HS: I don’t want to press you to answer something that you don’t want to answer.

JS: I think at the moment everything is going well.

HS: You’re still working on it?

JS: Oh, yes. And there are two or three serious projected buyers. But as I said, to me the most important thing is not just that there are projected buyers of that one manuscript, but the fact that it’s highly likely that there should be three or four others.

HS: As you look back on things, is there anything you would do differently?

JS: If I had had the foresight in 1954 that I had in 1985 when I became in charge of the Qumran project … I hope that I would have had the foresight to see already by 1960 that we were absurdly few in number for our task, that too few scholars were working on the project, and that we needed more people to be incorporated into the editorial team. I would have taken, not your position 057about the open availability of all documents, but at least tried to have got a much larger team together. I think we would have done better by just getting more people into the team than by trying to cast open all the photographs and to cast open the concordance. Also we should have been more serious about observing timetables, and about getting more financial support for the editors at an earlier time.

HS: Let’s talk a little about MMT [a 120-line text reconstructed from six different copies, edited by Strugnell and Elisha Qimron. Qimron sued BAR for reprinting the reconstructed text without his permission.] You recently changed your position. Initially you announced with Qimron that you thought MMT was a letter, and that it was from the Teacher of Righteousness [the original leader of the Qumran sect]. Now I understand that you’ve changed your position, that you no longer say it’s from the Teacher of Righteousness, and indeed you no longer believe it’s a letter.

JS: Well, when we were writing together in the late 1980s, we came to an agreement on the Qimron hypothesis that this was a letter composed by the Teacher of Righteousness addressed to the Wicked Priest, and so on.

HS: The priest in Jerusalem?

JS: Yes. I was happy with this and so was he. I, in fact, wrote the historical statement for our joint edition on this. He wrote a few small corrigenda and we left it at that. But in the two and a half years that then ran past, until the edition of MMT grew a little nearer—it’s not yet come out, but it’s almost come out—in those two and a half years I was still working in my corner of the globe on it and he was working in his corner. He was doing the final revision and I was making small modifications. In making these modifications, I asked myself, does this Qimron hypothesis fit the evidence? There was a major problem. It did not have the form of a letter at all. We know, in antiquity, what form letters had. It’s not just that they should be sent to you, from you, and so on. We know what should be the subject, we know what should be its introductory matter, and so on. And Qimron’s letter didn’t have either of these. Qimron’s MMT didn’t have any of these where it should have had them to satisfy his hypothesis.

HS: How did you happen to agree in the first place then?

JS: Because we didn’t think about the form-critical objections.

HS: You just followed Qimron?

JS: Well, I don’t know. We were working quite happily together. We were working more on the historical question of whether it would go with [the high priest] Jonathan or [the high priest] Simon, the sort of worries one has about the initial statements of this thesis. Later, I went much more at these documents from a form-critical point of view, looking at what the formal characteristics of the document are. And we don’t have the formal characteristics of a letter. We have different formal characteristics. We have the formal statement of what looks like a law code. We have an introduction about a calendar that has no second-person introduction at all. Finally, the law code looks as though it fitted onto a … Well, it’s very hard to say what it looked like. It’s the end of the work.

I then went through this text and asked myself, what does this give me in terms of the material contents of the document. Can we use certain elements of the old hypothesis or not? In the end I said no, I really don’t think so. We’ve got the calendar, we’ve got a law code, and a third piece, a sort of fragment sounding like Deuteronomy, the ending of a code of blessings and curses. That would make perfect sense. Now by this time Qimron’s book already reached about 500 pages long. The Oxford Press is having hesitations about the size of it. I don’t know whether, in the end, they’re going to put this in. I would have liked it to go in. It’s the most rational place for it to be put. But we’ll see how it goes.

HS: If that isn’t in it, then the editio princeps is going to come out with something you disagree with.

JS: Yes, but I have delayed this edition long enough.

HS: Wouldn’t it help to make public the text? It’s only 120 lines or so.

JS: Yes, but the text will be out by March [1994], unless they start printing my addendum. I don’t know.

HS: I have trouble understanding why you and Qimron don’t say, instead of talking about your arguments as to whether it’s a letter and whether it meets these criteria, instead of tantalizing people, why not just say look, here’s the 120 lines. Anybody can copy it, anybody can study it, anybody can do what they want with it. That wouldn’t hurt you, would it?

JS: No, but I have to recognize now that this thing has, to a large extent, become Qimron’s work. I mean, he took it over and got it into its final form when I was sick for two years. And so I have to leave it to him to decide that. He is not going to wait that long.

HS: But once it’s published, he still owns it.

JS: No.

HS: He has the copyright.

JS: No. As far as I understand, it’s going to be the Oxford Press that owns it.

HS: But someone will own it other than the public. If it were up to you, would you make it available right now?

JS: I would want to find out when the Oxford Press is going to have it available. And I think they’ll have it available. They tell me that there’s going to be a party in Beer-Sheva in April or May to celebrate. So you come along and be prepared to celebrate.

Harvard professor John Strugnell was chief editor of the official Dead Sea Scroll editorial team from 1987 until he was dismissed in late 1990, after giving an anti-Semitic interview to Israeli journalist Avi Katzman, in Ha’aretz, November 9, 1990, and “Chief Dead Sea Scroll Editor Denounces Judaism, Israel; Claims He’s Seen Four More Scrolls Found by Bedouin,” BAR 17:01. An original member of the editorial team, Strugnell had been studying the scrolls for over 40 years and was one of the most significant players in the Dead Sea Scroll drama. A brilliant, complex man, he has dropped from public […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username