An Off-Duty Archaeologist Looks at Psalm 23

044

045

The warm welcoming words, gentle pastoral setting, simple lyricism, strong sense of devotion and profound truth of divine love and care have made Psalm 23 one of the best-known and best-loved poems in the world. It is so famous that it has influenced the development of the English language. Transcending time, phrases from the King James Version of the Bible-like “the valley of the shadow of death,” “still waters” and “green pastures”—are so familiar that modern translations are loath to change them.

As an archaeologist working in Jordan, I found that many of my “off-duty” observations and experiences reflected the words of this famous psalm and gave me a new understanding of its message. Looking at it in the original language, Hebrew, added even more insights.

The Arab world and certain parts of Israel still have the strong presence of two groups of people practicing traditional desert culture: Arab villagers and the Bedouin. Some of their values and customs retain practices handed down from generation to generation for hundreds and hundreds of years. Working near these traditional societies has allowed me to observe how these people today use and are influenced by the land—and thereby better understand the psalm.

When I am not out digging, I explore the countryside. I have poked into countless crevices and ledges and even nosed my way into peoples’ backyards—usually with their permission. I have crossed miles of desert by foot to discover out-of-the-way ancient sites and sipped tea in scores of Bedouin tents, partaking of the legendary Arab hospitality and observing firsthand their dignity and pride. During these encounters, phrases from Psalm 23 often leaped to my mind.

Yahweh is my shepherd, I shall not want;

Hebrew literature, especially poetry, is filled with colorful, apt metaphors. The Israelites apparently loved double or multiple meanings, as their use of parallelism and puns suggests. Throughout verses 1–4 of the psalm, the metaphor of the shepherd can be consistently understood on two levels: down-to-earth reality—the shepherd caring for his flocks—and devotional symbolism—the divine shepherd’s care of his people.

The translator struggles to embody both the image of the actual shepherd and the devotional message in appropriate English words, but sometimes translations cannot present both.a Living in a culture where sheep are a part of everyday life, however, keeps the dual image firmly in mind.

Almost all traditional families (Arab villagers and Bedouin today) own flocks of sheep and goats, as did the ancient Israelites. Usually the family flocks are small, from five to fifteen animals. Villagers often combine their flocks and send them out with one shepherd, making the work of watching the flocks more efficient.

Children often serve as shepherds, as they are less productive in other capacities. Very few adults look forward to the boring work of watching sheep and goats graze all day. Many of the children break up the time playing on their Bedouin pipes, throwing stones or hanging around excavations. In the Bible, the shepherd boy David may have used his time practicing with his sling and playing his lyre.

But biblical shepherds also symbolize the work of kings, who shepherd their people instead of flocks (Jeremiah 23:4). The metaphor in Psalm 23 is thus more than a simple idyll, for it includes the element of royal care and protection. Just as shepherds and kings take care of their flocks, so God will care for us.

He makes me lie down in green pastures.

The region occupied by today’s Jordan and Israel has two climatic seasons: the rainy winter months produce lush, green fields from November to April; during the usually rainless summer from May to October, the plants go dormant and the landscape turns brown.

The botanical remains from excavations suggest that the climate of ancient Israel was similar to that of today. It was probably as difficult for an ancient shepherd to find good grazing ground as it is for his modern counterpart. During the winter and spring, the land blossoms and succulent green plants abound, but during the summer, most shepherds must search hard to find decent grazing for their flocks: The best land is used by farmers for crops and is strictly off-limits to crop-destroying animals. They must graze in marginal land where good food is not abundant, and sometimes travel long distances to find even that. The Bedouin, on the edges of the desert, must move their camps periodically to find new feeding areas.

The image in Psalm 23 is of flocks who do not 046have to be constantly roving the hills, but who luxuriate in so much grass they can even rest after eating. This is the plenty that God the shepherd provides.

He leads me beside still waters;

The central territory of ancient Israel was the mountainous country north and south of Jerusalem. Many of the valleys in this region are steep and narrow. The wider ones are cultivated by farmers; sheep are not allowed to graze there. Except for the Sea of Galilee, there are no natural lakes. Finding water is often a problem. Rains during the winter months fill the normally dry valleys with raging torrents, racing to the Mediterranean or the Dead Sea. Sheep can easily be swept away in the flood. For a few days after a storm, shepherds search out small pools left behind. Otherwise, they must find water sources created by springs, or haul water from wells.

The Hebrew word for “still” (menuchah) is better translated as “restful,” and carries a double meaning, describing both the calmness of the pool of water and the placid setting for the sheep. It is thus parallel to the preceding line where the sheep “lie down” in the fields. The Psalmist is saying that God’s protection gives (nahal; the Hebrew word for “leads” actually means “gives”) us rest as well as refreshment.

He restores my soul.

Here is an example of a word with a double meaning, only one of which the translator can use. The Hebrew word for “soul” (nefesh) also means “life.” On the literal level of the metaphor, the word should be translated “life,” but on the devotional level, the translation “soul” is fitting. In a dry land the good shepherd tries to maintain the “life” of his flock, just as God’s care enhances our soul in an oppressive world. After eating and drinking their fill, the animals are revived and refreshed; similarly, after spiritual food and water, the individual is calmed and fortified.

He leads me in paths of righteousness

The countryside has thousands of interconnecting sheep and goat tracks looking like a massive web covering the hills. Made by wandering flocks searching for food, these trails create a never-ending maze, especially on 047the eastern—less watered—slopes of the hill country. The flocks don’t know where to go by themselves and need the shepherd to guide them to the best grazing.

The Psalmist carefully chose his words in this line to evoke this picture: the word for “leads” (nachah) means “guides,” as if the flocks are confused with the maze of paths; the word for “paths” (singular: ma‘gal) is based on a Hebrew root which means “rolling” and refers to the tracks running over the rolling hills; and the word for “righteousness” (tsedeq) can also mean “straight.” In fact, this may have been its everyday meaning. The idea of “righteousness” may have derived from being “straight” with the law of God.

Thus, this line may be understood in two separate ways, one corresponding to the literal level—“He guides me in straight tracks”—and the other to the devotional level—“He guides me to the ways of righteousness.” Ancient Israelites undoubtedly saw both ideas.

For his name’s sake.

For many people this line does not make much sense. What does God’s name have to do with it? Although the Bible itself holds the key to this phrase, the speech habits of Muslim Bedouin and villagers also help explain it. When the Bedouin and the villagers converse, the word w’allah (or its classical variant w’allahi) constantly crops up, sometimes more than once in a sentence. Meaning “by God,” it is a mild oath indicating that what the speaker says is most certainly true. Although quite perfunctory today, it originally meant that the speaker, if not telling the truth, is denying God, implying an utterly unthinkable thing to do.

In the Bible, vows are initiated by an oath. David frequently swore, “As the Lord [Yahweh] lives ….” When he used the name of God like that, he was duty bound to do what he said or he would be denying God. The third commandment expressly forbids using the name of God in this way falsely. Oaths were taken extremely seriously in biblical times because the integrity of society was based upon them. Since each line of Psalm 23 has both a literal and symbolic meaning, it seems likely that this line also bears a literal meaning—that shepherds took oaths to protect the sheep they pastured. Such an action would be most appropriate if one shepherd took out flocks belonging to several families.

Covenant ceremonies also used oaths in the name of God to make the agreements legally binding. Thus, Jacob and Laban swear by Yahweh at their covenant ceremony in Genesis 31:49. But when God makes a covenant with his people, by whom does he swear? Obviously, he has no God. He would have to swear by his own name, as the phrase in Genesis 22:16 implies: “By myself I have sworn.” In Psalm 23, then, the Psalmist is saying that, because God has sworn to uphold his end of the covenant protecting his people, he will indeed do it, or he is not God.

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil; for thou art with me;

At this interesting point, the language of the poem changes from third person to first person as if to remind us that the metphor is describing our devotional experience with God, not simply the habits of sheep and goats.

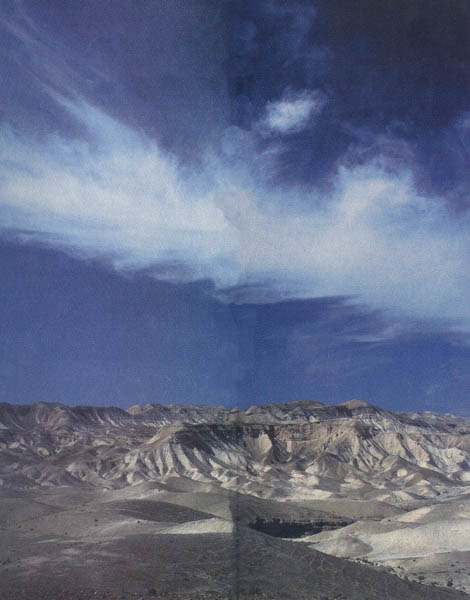

The hills of ancient Judea and Samaria and east of the Jordan River are made of limestone, a rock that dissolves in water. Over time, torrential rains carve deep shadowed valleys into limestone masses, leaving the valleys surrounded by high cliffs dotted with thousands of crevices and small caves. They provided ideal hiding places for wild animals that preyed upon flocks and bandits that attacked travelers such as in Christ’s parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29–37).

The phrase, “valley of the shadow of death,” is so evocative that it has become firmly entrenched in our consciousness. The Hebrew is not quite so grim. It alludes to the deep canyons on the eastern fringes of the hill country. The root word (tsalal) emphasizes the darkness of shadow but has nothing to do with death. A more accurate translation would be, “the valley of deep shadow.”

Flocks prefer to graze on sunlit hills, not in deep, shadow-enshrouded valleys, just as people fear times of sorrow or doubt. Spiritual darkness threatens life as the danger of the dark canyon threatens the sheep, but with God’s protection, we have no fear.

Thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me.

Shepherds do not carry two staffs. As my teacher, George Ernest Wright, used to say, the Psalmist may be using two terms to emphasize the dual use of the shepherd’s staff in protecting the sheep: (1) it may be used to 048drive away or destroy enemies such as wild animals; or (2) alternatively, it can be used to prod the sheep so they keep moving forward and do not wander away from the flock. Throughout the devotional literature of the psalms, these two themes of divine protection are used. God destroys enemies (“ … the Lord maintains the cause of the afflicted, and executes justice for the needy” [Psalm 140:12]) and disciplines his own (“Against thee, thee only, have I sinned, and done that which is evil in thy sight, so that thou art justified in thy sentence and blameless in thy judgment” [Psalm 51:4]).

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of my enemies;

With verse 5 there is a clear shift in metaphor. Gone are the pastoral words of verses 1–4; present are words like “table,” “cup” and “house.” God is now seen as a host, offering hospitality to a guest. The Bible is specific about the treatment of strangers and aliens. Deuteronomy 10:18–19 says, “[God] executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing. Love the sojourner therefore; for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt.” Although the Bible speaks of hospitality in several places, a study of hospitality in traditional Arab societies adds spice to our stew.

Every good host feeds his guest a lavish meal, full of a great variety of dishes, which the guest is expected to eat robustly. As an archaeologist, I often find myself an honored guest at Arab tables. Countless times I have been compelled to overeat simply because I was foolish enough to finish the food on my plate, thereby signaling to my host that I was still hungry. It would be a great loss of face to the host if a guest left his house even slightly unsatisfied. The hospitality of the desert Bedouin is fabled. Stories abound in traditional Arab lore about the poor man who served the last animal from his flock to honor an esteemed (and rich) guest who happened by his tent.

The great feast of the Bedouin, the mensef, illustrates the high value placed on sumptuous eating. It is usually prepared for special occasions, such as weddings or end-of-dig parties. The host places generous amounts of boiled lamb over a large mound of white rice on a huge platter about 3 feet in diameter. Next, over the mound he pours a mixture of yogurt, coriander, pine nuts and the fat of the lamb. He places the head of the lamb, with jaws agape, at the top. The guests eagerly 049gather around and, using their right hands, form balls out of the rice, meat and sauce to pop into their mouth. Although it has never actually happened to me, it is said that the guest of honor gets the eye!

Not only should the table hold a feast, but the host is (theoretically) duty bound to protect his guest with his own life, even if he should find out the guest is an enemy. Thus Lot, in Genesis 19:3–9, was willing to sacrifice his own family to protect his guests because he was a righteous man, fulfilling his obligations as a host amidst all the evil of Sodom.

During the recent Gulf War, Saddam Hussein called hostages forcibly retained in his country “guests.” Although this sounded like a cruel, silly joke to most Westerners, it probably was intended as propaganda for his own people, suggesting that in line with their strong tradition of hospitality to foreigners, the captives were being treated in an honorable fashion.

In Judges 19:20–21, a man took strangers into his home with traditional words of welcome: “ ‘Peace be to you; I will care for all your wants; only, do not spend the night in the square.’ So he brought them into his house, and gave the asses provender; and they washed their feet, and ate and drank.” When men of the city violated the laws of hospitality by rape and murder, all Israel rose up to punish them for their wickedness (Judges 20).

These are the strong values behind the hospitality metaphor in Psalm 23. The Psalmist is saying that, although our enemies are pounding at the door, we are secure in our knowledge that God, the good host, will protect us.

Thou anointest my head with oil;

For most of us in Western cultures, this line suggesting it is nice to have oil running down our head and dripping onto our shoulders sounds like greasy kid stuff. However, among the people rooted in the dry lands of the Bible, fat and oil are symbols of luxury. When my wife and I visited the home of one of our village workmen, his mother was intensely interested in my wife’s chapstick and hand lotion, items which seemed very minor to us.

But anointing the head with oil also speaks of the quality of the feast prepared for us. In the Bible, only kings and priests are anointed. This provides a connection with the first metaphor of the psalm. There, shepherds were symbols of kings. Here, when God is our host, he treats us like royalty.

My cup overflows.

050

On one occasion I visited an archaeological site far from any access road. While walking across the hills, I passed a Bedouin tent. The sun was high and the day was warm. Sitting in his small, ceremonial room enjoying the breeze, the owner saw me pass and probably knew what I was up to. After all, only mad dogs and archaeologists go out in the noonday sun! On my way back, he was ready for me. Like Abraham (Genesis 18:2–8), he ran out of his tent and invited me in to drink tea. Hospitality offered like this is meant to give face to the guest. To refuse would be a serious breach of etiquette. Stories of the old days tell of rejected hosts brandishing weapons at guests who refused hospitality. Needless to say, I did nothing of the kind!

I settled crosslegged on the fine carpet in the ceremonial part of the tent while the tea finished brewing. We talked politics, partially because Arabs love it, but primarily because in my halting Arabic it is easy to use names and simple words like “good” or “bad.” As we talked, I could hear his wife bring her work close to the other side of the separating curtain, just as Sarah apparently did (Genesis 18:10).

Bedouin tea is very sweet, almost syrupy, to give energy and honor to the guest. Often it is laced with herbs and spices to give distinctive tastes. Although I tried to leave several times while we drank and talked, he would not let me go until I had downed seven cups of his brew! As I sloshed out of his tent, I thought of Psalm 23: my cup had indeed overflowed!

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life;

Two aspects of hospitality in this line of the psalm are not immediately clear in translation. In Hebrew, the term for “follow” (radaf) is often used when armies pursue, or chase, one another (Joshua 7:5). Sometimes, the word has the nuance of “harass” (Psalms 109:16). Like my Bedouin host with the tea, God chases, or even harasses us with the best that hospitality can give. The Psalmist uses a negative word to show how strongly God wishes us to accept the good things he offers.

The second aspect of hospitality in the line is the phrase “all the days of my life.” Usually, a guest may partake of traditional Arab hospitality for a maximum of three days. After that, it is good grace on the part of the guest to make an excuse to leave. That the Bible had a similar view is clear from Judges 19:4–5, where an Ephraimite stayed three days before suggesting departure. His host, however, implored him to stay longer. When God is our host, we are invited to stay not just for three days but “all the days” of our lives.

And I shall dwell in the house of Yahweh ever.

The Hebrew word for “dwell,” veshavti, seems to combine two separate Hebrew verbs.1 The word 051shuv actually means “return.” In normal Hebrew usage this verb is followed by the preposition “to.” But at this point the Psalmist confronts the reader with the unexpected preposition “in,” as if he is thinking of the similar verb “dwell” (yashav). When we combine the meanings of the two verbs, the psalm is suggesting that, no matter where we are or what we are doing, we will always return to dwell in God’s house, partaking of his hospitality.

There is probably another idea suggested by a pun on the spelling of the Hebrew word as it appears in the text (shavti). The consonants and first vowel are the same as the word for “sabbath” (shabbat), suggesting, by association, the peace and rest that we obtain when we receive hospitality God’s house.

Although the Psalmist’s use of “house” probably piously alludes to the temple, it may also continue the royal allusions by referring to a palace. The Psalmist is not saying that, as I used to think when I was a child, we would be trapped in church or synagogue forever, but that we will stay in this house of God, where we receive the best that royal hospitality can offer, for as long as we wish. God, our shepherd and our host, will provide whatever we need.

The warm welcoming words, gentle pastoral setting, simple lyricism, strong sense of devotion and profound truth of divine love and care have made Psalm 23 one of the best-known and best-loved poems in the world. It is so famous that it has influenced the development of the English language. Transcending time, phrases from the King James Version of the Bible-like “the valley of the shadow of death,” “still waters” and “green pastures”—are so familiar that modern translations are loath to change them. As an archaeologist working in Jordan, I found that many of my “off-duty” observations and experiences […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username