Ancient City of David To Be Re-Excavated

042

A major new excavation will begin this summer in the oldest inhabited part of Jerusalem. Known as the city of David, the site is located on a dusty ridge south of the present Old City. The following article is by the man who is responsible for initiating the project and raising the money to finance it.—Ed.

Many of us deeply feel that our ancestral history is to be found in the pages of the Old Testament. In the Holy Land lie the tangible remains of our forefathers—a kind of ancient time capsule—linking us inseparably with our past. Like Schliemann digging for Troy with Homer as his guide, so we have dug for our past and our ancestors with the Bible as our guide.

It was inevitable that after the unification of Jerusalem, I rushed to Israel with my wife to wander through the Old City. We walked through the narrow, crowded streets filled with peddlers and shoppers, past the tumbled stones of destroyed synagogues, up to Mt. Scopus to gaze over the whole city—a unique mixture of both ancient and modern. Then we went to the dusty hill south of the Old City on which the original city of David is located, to the Jebusite town that King David conquered and designated the capital of my people.

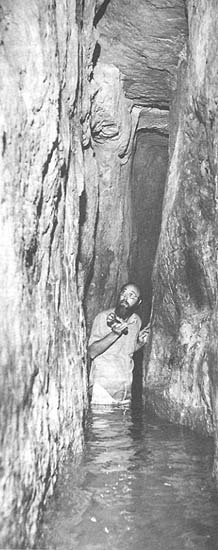

During one of our strolls—on a clear, hot summer day—I arrived at the Spring of Gihon, whose waters provided a cool respite from the seasonal heat. Though I had arrived unprepared for exploring Hezekiah’s tunnel (which begins at the spring), I was soon ready for the adventure—stripping down to a pair of shorts, and equipped with a candle provided by an enterprising young Arab boy. The passage varied in size; sometimes I was able to stand erect but often I had to crouch down low or risk getting stuck. For over 1,700 feet I pressed on, sensing perhaps a feeling similar to what those early tunnelers must have felt when they accomplished this technical feat.

Hezekiah’s tunnel (which is referred to in the Bible: 2 Kings 20:2; 2 Chronicles 32:2–4, 30) and Warren’s shaft (connected to the tunnel and spring by a steep vertical passage) were for defense purposes—to assure safe and secret access to water during a state of siege. The water source (outside the city wall) is covered, and the tunnel provided a passage under the wall to the inside of the city.

The spring’s importance is undisputed—water in a besieged city is its life blood. And Gihon supplies the only running water reasonably accessible to Jerusalem from inside the city. According to the Bible. Hezekiah’s tunnel saved the city during the siege of Sennacherib at the end of the 8th century B.C.

I kept returning to the largely ignored little ridge of the City of David on other visits to Israel. With Hershel Shanks’ City of David in my hand, I explored the surrounding area—the Jebusite wall from 1800 B.C. that disappeared under a later Israelite wall, Israelite houses destroyed by the Babylonians, a necropolis that may have been the royal burial place for Judean kings, a Hasmonean tower.

In February, 1977 I went again to my favorite spot in Jerusalem with a party of friends. This time we could not walk through the tunnel, so we satisfied ourselves by falling in at the point where the spring gurgled forth above ground.

But each time I came to this spot, I was filled with a mixture of elation and disappointment—even embarrassment. I noticed how unkept and neglected the area was, and I felt a sense of outrage at the injustice of having a symbol of our beginnings used as a dump. I decided something must be done to 043remedy this unfortunate situation.

I approached Jerusalem’s Mayor, Teddy Kollek, and the Jerusalem Foundation, a charitable foundation that often sponsors projects relating to Jerusalem. Together we changed the seeds of thought into a blossoming project.

I thought that I could accomplish two goals at one location—an exploration into history and the restoration of the site so it would be a place of beauty for all to enjoy. To the scholar, this area was still replete with unanswered questions and well warranted renewed excavation, despite the fact that it has attracted archaeological attention for over 100 years But our plan also included immediate restoration of the archaeological remains and the ultimate creation of an archaeological garden that would fit into the city of Jerusalem’s long-term design.

Teddy Kollek enthusiastically arranged a meeting between myself, Dan Bahat and Avi Eitan, both of the Department of Antiquities, Yosef Aviram of the Israel Exploration Society and Ruth Cheshin of the Jerusalem Foundation.

As usual, the problems of beginning a dig were many. (See “How A Dig Begins,” BAR 03:02) . Under whose auspices could a dig of this nature be organized? How could we obtain the financial backing? Which archaeologist would direct the excavation? Who would control the administration? How do we incorporate Kollek’s idea of restoring the area and leaving it as an archaeological garden after the dig? How do we treat the financial sponsors? How quickly do we make available the results of the dig and in what kind of publication?

As one might imagine, there are great difficulties in answering so many questions long before the commencement of the project. It took six months of discussion and study to arrive at an agreed plan.

We decided that the dig would attempt to answer questions concerning the area surrounding the Spring of Gihon and containing the Bronze Age city of Melchizedek, the pre-Israelite Canaanite city, and the Iron Age town of King David.

Under the direction of the well-known archaeologist, Dr. Yigal Shiloh of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, this extensive project will attempt to trace the origins of town life within a triangular area extending southward to the Pool of Siloam, and enclosed on the east and west by the Kidron and Tyropoeon Valleys and northward by the southern wall of the Temple Mount.

As a South African Jew, my aim is to create a link between the South African community and 044Israel that will awaken and stimulate the pride of ancestral roots in both young and old. Those members of the South African Jewish community who will sponsor the project and all other South Africans who are interested can be expected to participate in this joint cultural and scientific venture. I hope that I will have the pleasure of seeing my children and many other children join in the dig, attend seminars in Israel and take part in a small segment of Israeli life. In this way, many will be educated in a living laboratory of their past and will show the world that in all areas we are one people with one heritage and a determination to share one common destiny.

Under the auspices of the Israel Exploration Society, the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University and the Jerusalem Foundation, the dig will be under the combined directorship of those people that I have mentioned who were involved in preliminary discussions and who now comprise the Board of Directors of what in the States would be called a non-profit corporation. They will represent the financial sponsors (a “minyan”a of contributors whom I have collected). The Board will control the financial and administrative aspects of the project, including the preparation of annual budgets and monthly cash flows. The archaeological decisions will of course be made by Dr. Shiloh.

At the outset, we have allocated 20% of the money for restoration and publication, and hope to begin the first season not only by excavating but also by restoring. Subject to the final decision of the archaeologists, we hope to begin this summer with the restoration of Warren’s shaft. This shaft is now almost inaccessible despite the fact that it is one of the most impressive remains of Biblical times. Many scholars believe that it was through this shaft, originally constructed by the Jebusites, that David’s general, Joab, first gained access to Jerusalem, thus enabling King David to conquer the city. (See 2 Samuel 5:8; 1 Chronicles 11:6)

I feel that this area must not only be excavated and restored, but must be made available to all people as an archaeological garden. In it, all will be able to wander through 4000 years of our history.

But I also want to tell the story of the dig and relate our trials and tribulation, joys and sadness, excitement and boredom along with that segment of Jerusalem’s history we shall uncover, spanning the years when the City of David developed from a tiny crossing between the great empires of the Nile and the Euphrates to the pulsating heart of the Israelite kingdom.

A major new excavation will begin this summer in the oldest inhabited part of Jerusalem. Known as the city of David, the site is located on a dusty ridge south of the present Old City. The following article is by the man who is responsible for initiating the project and raising the money to finance it.—Ed.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username