Archaeology Odyssey’s 10 Most Endangered Sites

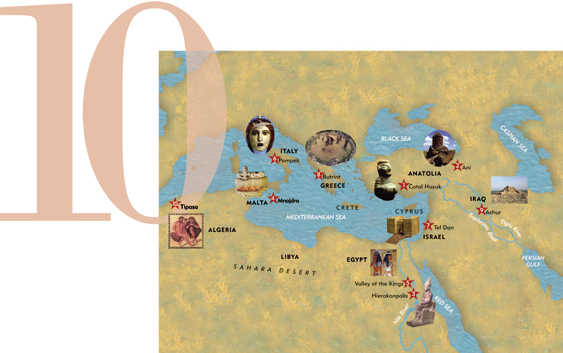

014

Any choice of the “10 Most Endangered Sites” is, at most, a kind of informed arbitrariness. Although all of the sites on our list are archaeologically important and in imminent danger, some have more value than others and some face greater threats. Our ranking takes both factors into account, as well as the collective judgment of the World Monuments Fund, which publishes the biennial World Monuments Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites (the 2002–2003 list adds the World Trade Center as a 101st site). Following are Archaeology Odyssey’s 10 Most Endangered Sites from the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern world, in the order that the editors have ranked them—though you may think differently.

016

1. Catal Hoyuk

The World’s First Town

Turkey

Early 8th millennium B.C.

Some 9,000 years ago, in a grassy region of south-central Turkey, a group of hunter-gatherers discovered a new means of survival: farming. They then established a settlement that over the next millennium would grow to 32 acres and house up to 10,000 people.

This Neolithic settlement at Catal Hoyuk (cha-TAHL hoo-yook) was first excavated in 1961, when James Mellaart of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara sank a trench in the site’s 65-foot-high mound. Over the next five years he uncovered a honeycomb of almost identical, rectangular, flat-roofed mudbrick houses, which had square living rooms leading into long, narrow storerooms. Each of the houses contained about 270 square feet of living space, suggesting that they were residences of nuclear families. Windows were placed up high, near the roof, and the open spaces between the houses were used as garbage dumps. Curiously, the houses had no doors. Our Neolithic ancestors used portable ladders to enter their houses through the roof.

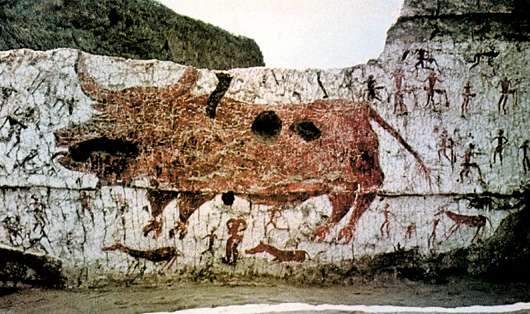

Mellaart’s team found both earthenware and wooden vessels, as well as small beads and pendants hammered out of copper. They also found lovely works of art. The 017abundance of small female figurines with exaggerated sexual organs led Mellaart to believe that Catal Hoyuk was a matriarchal society engaged in cultic worship of a Mother Goddess. On the walls of many houses, excavators found images of bulls, lions, leopards, flowers, stars and human hands. Some walls had terrifying depictions of vultures attacking headless humans. Among these remarkable wall paintings and reliefs was a depiction of an erupting volcano—perhaps the world’s oldest landscape painting.

Catal Hoyuk’s art was preserved by the white mud plaster that was regularly applied to building walls. One building had 120 layers of protective coating.

Mellaart’s spectacular career at Catal Hoyuk came to an abrupt halt when the Turkish government banished him for allegedly smuggling artifacts out of the country. Catal Hoyuk was then abandoned, with its now-exposed mudbrick walls left prey to the elements and to looters.

In 1993 excavations at Catal Hoyuk were resumed under the direction of British archaeologist Ian Hodder. Hodder’s international team of archaeologists, scientists and conservators found that most of the houses contained private areas dedicated to cultic worship—suggesting that this was probably not a community organized under a central priestly authority, as was the view of Mellaart. According to Hodder, the cultic rituals practiced at Catal Hoyuk probably had to do with death and the afterlife. Two or three generations of each family’s dead would be buried beneath the floor of their living room—then the dwelling would be abandoned and burned. The family would then level the area and build a new house on top of the old.

Only a small part of Catal Hoyuk’s mound has been excavated, but decades of neglect have made the exposed ruins vulnerable. On-site labs are being built to facilitate the conservation of mudbrick walls (though this has proved largely futile), and delicate finds have been removed to museums. Shelters will eventually be constructed over the site’s exposed areas, but the size and extreme fragility of Catal Hoyuk make it difficult to protect.

018

2. Ani

Easternmost Christianity

Turkey

Mid-1st millennium to mid-2nd millennium A.D.

Spectacularly perched on a plateau in northeastern Turkey, the city of Ani once rivaled Constantinople in splendor. A thousand years ago, its 100,000–200,000 citizens strolled down well-lit streets drained by underground pipes and worshiped in churches constructed of red and black stone.

Ani’s ancient Armenian rulers (who claimed descent from David and Solomon) reigned over an area covering most of northeastern Turkey and modern Armenia. They amassed enormous wealth by controlling the east-west trade routes between central Asia, Syria and the Byzantine Empire that passed through their kingdom.

As early as 306 A.D.—six years before the Roman emperor Constantine privately converted to Christianity (the official conversion came on his deathbed)—the Armenian ruler Tiridates III embraced Christianity, making Armenia the first country to establish Christianity as its state religion. The Armenian catholikos (pontiff) established a seat in Ani, and by 992 A.D. 12 bishops and 500 priests resided there.

Despite Arab, Byzantine, Seljuk, Georgian and Kurdish invasions, Ani remained an active trading center until the mid-13th century, when the Mongols captured the city. After a great earthquake destroyed many of Ani’s buildings in 1319, the nomadic Mongols showed no interest in rebuilding the city’s infrastructure. Some decades later, Tamerlane (c. 1336–1405), the ruler of Samarkand and conqueror of southern and western Asia, seized control of Ani, causing caravan routes to shift permanently away from the city. By 1441, the Armenian catholikosat was transferred to Yerevan, near the Iranian border of modern Armenia, and Ani faded into oblivion.

Today, only the magnificent shells of eight churches, a convent and a citadel remain standing in this city once fabled for its “thousand and one churches” and 100 gates. The first archaeological excavations of Ani got underway in 1892, when Russia incorporated the region into its empire. Over a 25-year period, Russian archaeologist and orientalist Nikolai Marr surveyed the entire site, uncovered the city’s walls and established a museum. During the Soviet period that followed, Turkish authorities restricted access to the site because of its proximity to the border of the former Soviet Union. Since the collapse of the USSR, however, restrictions have eased and tourists can once again travel to eastern Turkey.

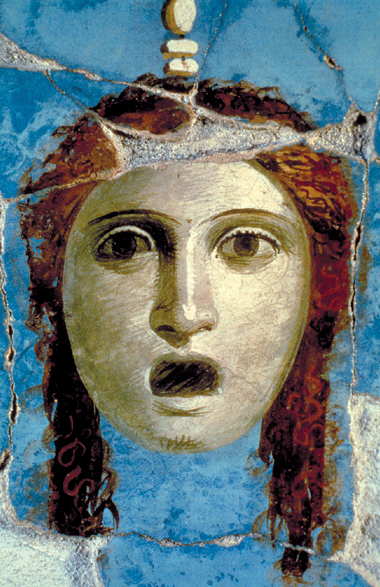

There they can visit the three remaining churches that are dedicated to St. Gregory the Illuminator, the fourth-century apostle to the Armenians. The Church of St. Gregory (above), built by a pious nobleman in 1215, has interior and exterior frescoes depicting scenes from the Bible and the life of the missionary-saint that are astonishingly well-preserved, considering the harshness of the region’s weather. (Ice damage is common in this high, wind-swept plateau where winter temperatures plunge dozens of degrees below zero.)

When another Church of St. Gregory (the Gagikashen) was excavated in 1906, a statue of King Gagik I—who ruled over Ani in the 11th-century—was uncovered. The 7-foot-tall sculpture of the turban- and caftan-clad king holding a model of his church was probably originally installed on the facade of the building. The statue disappeared following World War I, although a fragment of the king’s torso has recently been recovered.

Today, the late-tenth-century Ani Cathedral—designed by the same architect who rebuilt the dome of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia when it collapsed following an earthquake in 989—retains its roof, although the northwest corner of the building collapsed during a devastating earthquake that struck in December 1988.

Nearby are the remains of the circular Church of the Redeemer, dating from the same period. Half of the building collapsed during a lightning storm in 1957. In recent years a team of international experts has traveled to Ani to perform an emergency stabilization of the Church of the Redeemer. Ani’s crumbling buildings are not only threatened by the earthquakes that frequently strike the region, but by the digging of local treasure hunters. Tourists have defaced some of the frescoes within the city’s churches and Armenian inscriptions have been covered by graffiti; yet Turkish authorities—who have shown little interest in preserving this Armenian heritage site—usually paint over the damaged areas instead of conserving them.

Not surprisingly, Ani has been placed on the World Monuments Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites.

020

3. Hierakonpolis

A Pharaoh’s Palace of Eternity

Egypt

4th millennium B.C.

The capital of predynastic (late fourth millennium B.C.) Egypt lies on the west bank of the Nile, about 450 miles south of Cairo. Because it had long been associated with the hawk-god Horus, the patron of kings, the Greek conquerors of Egypt named the city Hierakonpolis (hyra-KON-plis), or City of the Hawk.

Just outside Hierakonpolis looms a 220-foot-long mudbrick structure called the Fort, which was in fact a ceremonial enclosure of Pharaoh Khasekhemwy, the last king of Egypt’s 2nd Dynasty (2770–2649 B.C.). From this sanctuary, the king carried out his religious and political duties in life and presumably throughout eternity. Although we know little about the rituals conducted in the enclosure, a building inside the complex may have been a palace richly adorned with granite columns and carvings and perhaps even statues. (Khasekhemwy had a pair of statues of himself erected in Hierakonpolis, including one [below] now displayed at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. These statues are thought to be the earliest depictions in the round of a historical figure.)

Nor do we know very much about Khasekhemwy, though inscriptions suggest he had trade relations with Syria and was a vigorous conqueror, raiding Nubia and putting down rebellions in Upper and Lower Egypt.

The Fort is the oldest unfired mudbrick building in Egypt—and probably the oldest freestanding masonry structure in the world. The walls, which enclose a 41,000-square-foot rectangular court, are still preserved in places to their original height of 30 feet. The building’s facade was originally whitewashed and inset with decorative niches (above) to create a paneling effect.

021

The Hierakonpolis Fort served as a model for the construction of the pyramids. A huge workforce had to be organized, for example, simply to make the 4 million mudbricks of the building’s walls and interior structures. Khasekhemwy’s son Djoser (2630–2611 B.C.), the founder of the 3rd Dynasty, was the first Egyptian king to use stone on a monumental scale in building the Step Pyramid at Saqqara—the first pyramid complex.

Khasekhemwy’s architectural masterpiece is deteriorating at such an alarming rate that the World Monuments Fund lists it among the 100 most-endangered sites in the world. Treasure hunters and locals scavenging for building materials have cut large holes in the building’s walls, further destabilizing a structure already compromised by the careless excavation undertaken a century ago by the English archaeologist John Garstang.

The northeast corner of the enclosure partially collapsed just a few months ago. Both the western wall and the south wall, which has still-intact niches, are also at risk of collapse.

Some steps have already been taken. Hierakonpolis has been designated a protected antiquities zone by the Egyptian government, the site has been carefully photographed, and surveyors have generated an accurate ground plan of the Fort. Renée Friedman, director of the American expedition to Hierakonpolis, has applied for a grant from the World Monuments Fund to stabilize the enclosure’s most critically damaged areas.

More information can be found online (www.hierakonpolis.org).

022

4. Mnajdra

Stonehenge South

Malta

Mid-4th millennium B.C.

023

Malta’s mysterious megalithic temples are a thousand years older than even the Great Pyramids of Egypt. One of these ancient structures, the Temple of Mnajdra (m-NYE-drah, with the second syllable rhyming with “bye”), perched on a rocky promontory 300 feet above the sea, may also be the world’s earliest astronomical calendar.

The main entrance of the kidney-shaped temple faces east to catch the first rays of light during the spring and autumn equinoxes—when the sun’s rays strike the rear wall of an inner chamber and illuminate the main axis of the temple. During the summer solstice, early morning sunlight lights up the edge of a stone pillar on the left side of the entrance chamber, and a pillar on the right is illumined as the winter solstice dawns.

Why did the Maltese go to such lengths—hewing and hauling 12-foot-high, 20-ton stones without the aid of metal tools or wheels—to track solar cycles? Perhaps they thought they needed precise indicators of seasonal changes to ensure the health of their crops.

The Mnajdra temple, like the six other Neolithic temples on the Maltese islands of Malta and Gozo, also served a religious function, perhaps associated with a fertility cult. Numerous “fat lady” statuettes—with ample buttocks and breasts—have been found in the temples.

The Mnajdra complex consists of two multi-lobed temples aligned along a central axis adjacent to a small trefoil unit that may have been priests’ quarters. High stone portals lead to narrow corridors and chambers containing altars, libation holes and rope holes used to tether sacrificial animals. A number of wall slabs contain small, rectangular openings, commonly referred to as “oracle holes.” Some scholars suggest that worshipers sought guidance from a priest seated behind the opening.

Over the millennia, salt spray, wind and rain have eroded the soft globigerina limestone of the interior chambers. Even the more durable coraline limestone of the external walls has been eroded by salt and pollutants. To make matters worse, a quarry not far from the site produces vibrations that rattle Mnajdra’s bones.

In recent years, a drainage system has been built to reduce erosion at the base of the megaliths. Plans are also being hatched to cover the temple with protective domes.

Mnajdra’s greatest enemy, however, is man. In April 2001, for example, vandals toppled and defaced more than 60 stones in the complex.

A $50,000 grant from American Express and money raised by a local newspaper have funded the repair and re-erection of the temple’s megaliths. New fencing now encloses the site, night lights have been installed and 24-hour guards posted. Malta’s culture minister, Louis Galea, called for international assistance in establishing a Maltese Temples Survey Project. With the aid of laser scanners, three-dimensional images of Mnajdra and other structures will be created for posterity. Mnajdra has been listed as one of the World Monument Fund’s 100 most-endangered sites in 2002. More information on Malta’s endangered prehistoric temple sites can be found online (www.otsf.org).

024

5. Valley of the Kings

City of the Dead

Egypt

Mid-2nd millennium B.C.

Nearly 3,500 years of grave robbers, windblown sand and flash floods have taken their toll on the Valley of the King’s magnificent tombs. Now tourists—about a million a year—pose an even graver threat to this necropolis on the west bank of the Nile across from Thebes: Their feet, hands and breath have caused irreparable damage to the tombs’ wall paintings. Not surprisingly, the World Monuments Fund has placed the Valley of the Kings on this year’s list of the world’s 100 most-endangered sites.

Why did New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) rulers choose to spend eternity in this deserted dry river valley? Perhaps for topographical reasons: Across the Nile from their capital, Thebes, the western horizon—associated with the setting sun and thus the realm of the dead—was dominated by an impressive, pyramid-shaped massif known as el-Qurn. As the king’s funeral cortege left Thebes and headed west, it symbolically paralleled the voyage of the dying sun and the journey of the dead into the afterlife.

Early in a pharaoh’s reign, a site within 025the necropolis was selected for his tomb. Two teams of 25–50 workers would labor in continuous ten-hour shifts to create the narrow, sloping corridors and recessed chambers of the tomb. Even relatively modest tombs took five years to complete. New Kingdom tombs were filled with lavish burial goods—jewelry, perfumes, furniture and food—all that a pharaoh might need as he negotiated his way through the netherworld.

Once the pharaoh was entombed, the burial vault was plastered shut and stamped with the seal of the jackal-god Anubis, a god associated with mummification. Then the entrance was covered with earth to hide any sign of the tomb.

One problem with this desert location, however, is that even infrequent rains produce destructive floods. According to Robert K. Vincent, Jr., director of the flood-mitigation project run by the American Research Center in Egypt, the walls of many tombs have been damaged by flood-borne debris, and alkaline water has leached into their interiors, causing the plastered walls to flake and destroying wall paintings.

Despite the valley’s remoteness, looters have tunneled their way into most of the tombs, only a very few of which have been found intact. A more sophisticated type of plunder got underway in the early years of the 19th century, following Jean-François Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphics in 1824. Suddenly, Egypt’s riches became coveted by European collectors, academics and adventurers, who swarmed to Egypt in search of mummies and artifacts.

A new era of archaeological excavation—stressing methodology, preservation and conservation—was inaugurated in the late 19th century by the great British archaeologist Flinders Petrie. The British draftsman Howard Carter, who learned his archaeology from Petrie in Egypt, brought these methods to the Valley of the Kings. Carter’s discovery of the largely intact, treasure-filled tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (1336–1327 B.C.) revealed just how sumptuous the looted tombs of the New Kingdom necropolis must have been. (Tut’s tomb—one chamber is shown below—had in fact been robbed shortly after his burial, though apparently only precious oils were removed.)

Carter’s find only enhanced the spell that ancient Egypt has cast over the modern West. The result has been a steady stream of tourists to the Valley of the Kings—creating yet another predation on the past.

026

6. Pompeii

When Time Stopped

Italy

Mid-1st millennium B.C. to 79 A.D.

When Mount Vesuvius rained down ash and hot cinders on Pompeii for three days in August of 79 A.D., most of the city’s residents escaped. The 2,000 remaining Pompeians were killed by a 200-mile-per-hour surge of superheated gas. Their corpses were soon covered by 20-foot-high mounds of volcanic ash and pumice that eventually solidified, leaving cavities in the earth when the bodies turned to dust.

The violent eruption put an end to 700 years of habitation at the site, which had first been settled by the Etruscans. By the fourth century B.C., Pompeii had become a medium-sized country town, with limestone buildings and orderly streets. Over the next 200 years, the city grew rich by exporting wine, oil and cloth. After the Roman dictator Sulla established a colony in Pompeii in 80 B.C., public buildings were erected in the city, including a theater that held about 20,000 spectators. A palaestra—a large enclosed courtyard where boys practiced gymnastic exercises—was constructed during the reign of Augustus (27 B.C.–14 A.D.).

During the Augustan period, Pompeii became Pompeii. Old temples were refurbished and elaborate new ones were built. Prosperous Pompeians put up bathhouses and basilicas. Over two dozen houses of prostitution have been uncovered in Pompeii, with bawdy frescoes advertising erotic specialties. Since the city’s demise came so quickly, signs on taverns, laundries and smithies still beckon long-dead customers. Election slogans and announcements of gladiatorial contests remain emblazoned on Pompeii’s commercial buildings.

This wealth is also evident in the city’s elegant houses, decorated with mosaics and wall paintings, and in the funerary monuments erected by wealthy families outside the city gates.

Extensive archaeological excavations, however, which have been continually conducted since 1748, have exposed the site to the elements. (So far, over 1,200 buildings and two thirds of the 163-acre site have been excavated.) Heat and humidity have fostered the growth of vines and weeds that crack the walls of the ruins; earthquakes have left buildings weakened; and inadequate roofing and the inappropriate use of resin varnishes and wax coatings have accelerated the decay of the city’s ancient frescoes.

Pompeii’s most pressing conservation problems are caused by the 2.25 million people who visit the site each year. Of the 64 houses open to tourists in 1956, only 16 can be visited today. But there is hope: A 1997 law permits Pompeian authorities to use gate receipts for conservation and site management purposes. In recent years, moreover, grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and American Express have supported conservation efforts, and the World Monuments Fund has restored the tomb of Vestorius Priscus, a prominent first-century A.D. magistrate who was in charge of Pompeii’s markets, public buildings and streets.

028

7. Tel Dan

From Canaan to Israel

Israel

Late 3rd millennium B.C. to Roman period

When Israeli archaeologist Avraham Biran sank the first trench at Tel Dan in 1966, he little suspected that over the next three-and-a-half decades he would uncover the world’s oldest mudbrick arched gateway and turn up the earliest extra-biblical reference to King David.

According to the Book of Judges, the tribe of Dan received no territory when Israel was divided among the Hebrew tribes following Joshua’s conquest. (Joshua 19:40–48 provides a slightly different version of events.) Searching for a homeland, the Danites eventually decided to conquer the Canaanite city-state of Laish in the north. After taking Laish, “they named the city Dan, after their ancestor Dan, who was born to Israel” (Judges 18).

With the dissolution of the united Israelite monarchy ruled by David and Solomon, the first king of the northern kingdom of Israel, Jeroboam I (924–903 B.C.), established cult centers in his northernmost and southernmost cities: Dan and Bethel. To wean subjects from the tradition of temple-centered worship in Jerusalem (the capital of the southern kingdom of Judah), Jeroboam may have re-instituted the Canaanite bull cult.

A thousand years earlier, the Canaanite inhabitants of Laish had built an enormous arched gateway leading into the city. About 50 years later this gateway was buried under a defensive rampart.

The triple-arched, mudbrick gate complex (originally coated in white plaster) was uncovered by Biran’s team in 1979 and 1980. The 50-foot-wide gateway (shown below and in the model above) is flanked by two towers, which have been preserved to a height of 47 courses of mudbricks (about 23 feet)—probably their original height. Remarkably, the three courses of bricks forming the gate’s arched entrance were discovered entirely intact.

Almost as soon as Biran began to uncover the massive portal, the mudbrick began to disintegrate. The Israel Antiquities Authority backfilled part of the site and erected a roof to protect the mudbrick from the elements; and last year, American Express contributed a $40,000 grant for conservation of the site. Nonetheless, scientists simply do not yet know how to preserve exposed mudbrick structures.

Over the years, Tel Dan has yielded city walls, a tomb with Late Bronze Age Mycenaean pottery, ritual artifacts such as stone altars and iron incense shovels, and Israelite cultic ruins. Biran uncovered Dan’s bamah, or ritual high place, where he believes a golden idol was originally installed.

Perhaps Biran’s most fascinating find were three fragments from a basalt stela dating to the late ninth century B.C. An inscription on one of the fragments refers to the “House of David”—the earliest extra-biblical reference to King David (c. 1004–965 B.C.) and the Davidic dynasty that ruled the kingdom of Judah.

029

8. Butrint

Troy in Miniature

Albania

Mid-1st millennium B.C. to mid-1st millennium A.D.

As early as the sixth century B.C., Greek traders settled on the acropolis above the deep, fjord-like harbor at Butrint. By the fourth century B.C., the city was one of the Greek world’s busiest commercial centers, with a population of 10,000. A temple dedicated to Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, was constructed during this period, as well as a theater, where modern beauty contests and folk festivals are staged.

The Romans took control of Butrint in the second century B.C., refurbishing the theater and building lavish villas and bathhouses. The city’s splendor was attested by the Roman poet Virgil (70–19 B.C.), who in Book III of the Aeneid describes Butrint as “a little Troy … that mimes the great one.”

In the Late Roman period, Butrint began a drift towards obscurity—which was halted, though only briefly, in the sixth century A.D., when Byzantine Christians erected two basilicas in the city, along with a massive baptistery with mosaic floors. As Butrint’s once-bustling harbor slowly silted up, however, the city was gradually deserted. In the late 1920s, the Italian count Luigi Ugolini persuaded Benito Mussolini that Butrint should be reclaimed as a symbol of Roman glory. Ugolini’s excavations uncovered Greek walls, the theater, several temples and the Byzantine basilicas and baptistery.

After the Second World War, Albanian archaeologists uncovered baths, temples and the Roman agora. Over the last 20 years, however, politics and poverty have prevented preservation of the site. Even the Butrint Museum’s showcases were looted during the civil unrest of 1997.

Now excavations have been resumed, the entire city has been surveyed, and restorers are working on the Byzantine baptistery’s marvelous mosaics. The Butrint Foundation (established in 1993 by the British peers Lord Rothschild and Lord Sainsbury, and financed by David Packard, heir to America’s Hewlett-Packard fortune), is working with the Albanian government to protect and conserve the site. In 2000, the Albanian government created a national park at Butrint, and UNESCO declared the area a World Heritage Site.

030

9. Ashur

Sacred to the Assyrians

Iraq

Late 3rd millennium to 1st millennium B.C.

The ancient Assyrian city of Ashur may soon be under water. A dam being built at Makhoul, 28 miles south of Ashur, will flood the lower portions of the site on the western bank of the Tigris River, and rising water tables may undermine the rest of the city.

The remains at the 160-acre site include massive, second-millennium B.C. fortifications, ziggurats, palaces, royal tombs and residential quarters. Ancient Ashur also had at least four major temples, including a temple of the love-war goddess Ishtar (third millennium B.C.) and a temple dedicated to the local god, the eponymous Ashur, who in the Neo-Assyrian period (early first millennium B.C.) became the chief Assyrian deity.

During the early second millennium, or Old Assyrian period, Ashur was an independent city-state enjoying trade relations with various Syrian, Mesopotamian and Anatolian peoples. By the tenth century B.C., it had become the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which eventually controlled a vast territory from Persia to the Levant. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 B.C.) relocated the capital north of Ashur at Kalhu (modern Nimrud), and later Assyrian kings built capitals at Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad) and Nineveh. Ashur remained the religious center of the empire, however, until it was destroyed by an army of allied Medes and Babylonians in 614 B.C.

The first excavations at Ashur were conducted by the British lawyer-explorer-archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s—though Layard put most of his efforts into digs at Kalhu and Nineveh. The site was systematically excavated in the early 20th century by Walter Andrae of the German Oriental Society, who determined the basic layout of the ancient city. Andrae’s excavation reports, however, were not published until the 1960s.

In the late 1980s, two German expeditions returned to Ashur. However, the Gulf War and the ensuing embargo stopped all archaeological activity at the site. In the late 1990s Iraqi archaeologists resumed work at Ashur, and in 2000 a German expedition headed by Peter A. Miglus of the University of Halle began excavating the site.

According to a member of the German team, Arnulf Hausleiter of Berlin’s Freie Universität, the current excavations are especially concerned with the domestic architecture of the ancient city.

031

10. Tipasa

Gateway to Africa

Algeria

Mid-1st millennium B.C. to mid-1st millennium A.D.

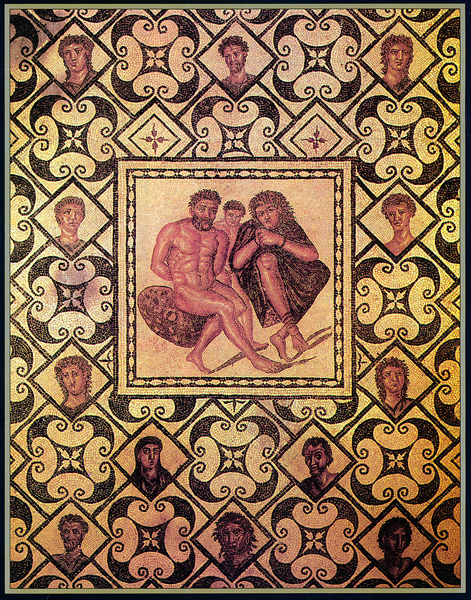

Shaded by fragrant pine and eucalyptus trees, romantic Tipasa boasts Roman ruins, a museum housing splendid first-century A.D. mosaics, a Christian basilica surrounded by an early Christian cemetery and a royal mausoleum built by local African kings. The site’s magnificent Mediterranean setting, however, inflicts a heavy toll on its ancient buildings: Salt spray and shifting ground levels have destabilized many structures (not to mention threats posed by new buildings illegally constructed near the ruins and Algeria’s political volatility).

Tipasa was first established as a Punic trading post in the sixth century B.C. By the second century B.C., the city had fallen under the domination of the kings of Mauretania, the realm of the Moors (a predominantly Berber people), whose territory extended from the Atlantic to the Atlas Mountains. The Romans wrested control of the city from the Berbers and turned it into a strategic base for the conquest of Mauretania, which was annexed to Rome in 40 A.D. One Berber from Mauretania, Septimius Severus of Leptis Magna, in Libya, was even named emperor in 193 A.D.

For Rome, control of North Africa meant steady supplies of gold, ivory, animal skins and slaves—along with the lions, elephants and other beasts that livened up theater performances. North Africa was also Rome’s chief source of garum—a savory sauce made from fermented fish.

In 1856 Tipasa’s first excavators revealed Roman ruins from the second and third centuries A.D., including a 4,000-seat theater, a forum, a basilica, a monumental gate and baths. During this period, a Jewish community at Tipasa built a synagogue. A Christian community took root in the city by the mid-third century A.D. In the early fourth century, a young Christian girl named Salsa—who would be canonized as Saint Salsa—was stoned and thrown into the sea by pagans. Later in the fourth century, a Christian basilica was built in Salsa’s memory on a promontory overlooking the city. Below the basilica lay a necropolis framed by wild olive trees and cypresses.

This history came to an end in 430 A.D., when Tipasa was conquered by Vandals, a Germanic people who had also overrun Italy. When Muslim Arabs arrived at the site in the seventh century, Tipasa had so deteriorated that they simply named it Tefassad (Badly Damaged).

Any choice of the “10 Most Endangered Sites” is, at most, a kind of informed arbitrariness. Although all of the sites on our list are archaeologically important and in imminent danger, some have more value than others and some face greater threats. Our ranking takes both factors into account, as well as the collective judgment of the World Monuments Fund, which publishes the biennial World Monuments Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites (the 2002–2003 list adds the World Trade Center as a 101st site). Following are Archaeology Odyssey’s 10 Most Endangered Sites from the ancient Mediterranean and Near […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username