Archelaus Builds Archelais

Herod’s son constructs a desert city that cecomes Pagan, then Christian

048

Herod’s son Archelaus was hated by his Jewish subjects no less than his father. Herod had left instructions that on his death leading scholars were to be put to death to ensure that there would be mourning when he died. This gives some idea of the attitude of the people toward him.

Archelaus was no less cruel. When protestors threw stones at Archelaus’s soldiers on one Passover, Archelaus responded by killing 3,000 of his countrymen in the Temple. “They were slain like sacrifices themselves… till the Temple was full of 049dead bodies.” So the event was described to Augustus in Rome, according to the contemporary historian Josephus.

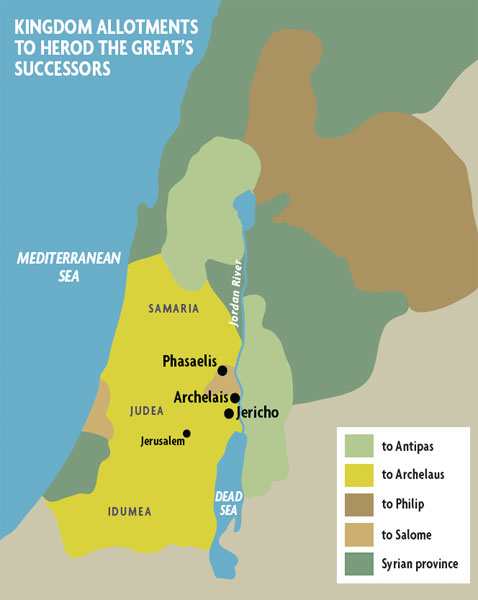

Herod died in 4 B.C.E. In his fourth and final will, he bequeathed his kingdom to his three sons. Archelaus got Judea (see Matthew 2:22) and Samaria, including the lower Jordan Valley. Before validly assuming the title of king, however, he needed the confirmation of the emperor Augustus in Rome. When Archelaus went to Rome seeking this, an embassy of his countrymen, citing his oppressive rule, asked that Judea be annexed to Syria, rather than have Archelaus declared king. Augustus compromised by naming Archelaus ethnarch. (Herod’s other two sons, Herod Philip and Antipas, who received other parts of their father’s kingdom, were given the title of tetrarch.) A decade later another Jewish embassy traveled to Rome to complain of the ethnarch’s rule. This time Augustus exiled Archelaus to Gaul in 6 C.E., where he died in 16 C.E.

Although Archelaus’s brief reign, like his father’s longer one, was characterized by unrest and 050oppression, he also inherited his father’s passion for building. Archelaus restored the royal palace in Jericho, and he founded a settlement in the Jordan Valley named after himself: Archelais. He was the only one of Herod’s sons to attempt to perpetuate his name in this way. (The spelling of Archelaus follows the spelling in Greek; the name of the village follows the spelling as it appears in Tabula Peutingeriana, a fourth-century map of the Roman Empire, an 11th-century copy of which was discovered in the 16th century and named by the owner. That’s the way these names appear in all translations and publications.)

For more than a decade, we excavated the settlement of Archelais,1 which lies just 8 miles north of Jericho, as part of a salvage operation initiated when a trench for a new telephone line damaged ancient remains. The site had been identified by a number of previous scholars, but the telephone line provided us with an opportunity to see what was really there—or at least get a taste of it.

The first question you might ask is, Why would Archelaus build a settlement here in what might be thought to be a desert? (It lies only 15 miles north of Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were 051found.) The quick answer is that this was really the only place available—and, all things considered, it’s not really such a bad location.

In the first place, it is located on the main road from Jericho to the north. Commercial activity along this route was brisk in ancient times.

Second, it could with reasonable effort be supplied with water. You might think water would come from the Jordan River. But that’s only a modern mind thinking. In ancient times it was not available in quantity because the river lies lower than the site of the settlement, which was built on a ridge. Numerous springs are the primary source of water in this area. The spring that supplied Archelais, however, is more than 5 miles away. Water from the abundant spring of el-‘Awja was conveyed to the valley by an aqueduct with two branches—one led to Na’aran and to the Hasmonean and Herodian palaces;a the other branch, to Archelais. From its point of separation into two branches, the aqueduct crossed a number of riverbeds, requiring the construction of small bridges. Remains of the aqueduct can still be seen. The aqueduct is almost 5 feet wide and 2 feet deep. At several points retaining walls protect it from collapse. Layers of plaster cover the bottom and sides of the aqueduct and in some spots the top of the retaining wall also. At Archelais itself the aqueduct is preserved for almost 4,000 feet. For much of this length, one side is carved out of adjacent bedrock and the other side by two rows of stones. Subsidiary channels carried water from the main aqueduct to the settlement and its fields. The steep slope between the level of the aqueduct and the settlement required the construction of small intermediate pools to reduce the rate of water flow. Water from the aqueduct was stored in reservoirs in the settlement and brought through conduits to other reservoirs and to the settlement’s agricultural fields.

The soil in the area is also watered by occasional rains that fall on the mountains to the west. The complex geological structure with its many narrow, steep canyons allows only about a third of 052the surface rainwater to reach the streams leading into the Jordan Valley. Those that debouch into the Wadi ‘Awja delta determined the location of the settlement and its adjacent fields.

Unfortunately, the soil is salty. To make saline soil arable, the fields needed to be flooded with water that was not saline, as we are told by the Greek geographer Strabo.2

With all this, does it seem like such a great site? Admittedly, it has its problems, but they are surmountable. And the truth is, as a practical matter, it was the only site available to Archelaus. Agricultural areas to the south belonged to Jericho; to the north, to a settlement called Phasaelis, built by Herod to honor his brother Phasael. To the west, Herod had bequeathed a small area to his sister Salome. Thus, the only open area available was in the runoff delta of Wadi ‘Awja. In short, Archelaus had no other choice of a location in this region.

But he made the most of it. The major structure in the settlement was a luxurious, spacious mansion of over 3,000 square feet. It was entered through a splendid portico or porch. Two column bases from the portico, set 8 feet apart, were found in our excavations. Inside the building was a large central courtyard, nearly 1,000 square feet in area. A row of columns subdivided the courtyard. The 053stylobate (the low but firm wall on which the columns were set) was still in place. Four column bases suggest that the courtyard was roofed on only one side, letting in light on the other side.3 On the other side we found a Doric column capital, indicating the Greek order of decoration that was used in the courtyard. East and south of the courtyard were the living quarters of the residents, rooms for guests and storerooms.

In the northwestern area of the courtyard was a mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath, confirming the ethnic identity of the occupants. The mikveh consisted of two pools (one with steps) connected by a shallow channel. The pool without steps is the otzer, or reserve, to supply the bathing pool.

We also found a number of stone vessels, not only typical of the Herodian period but also of Jewish settlements at this time. Unlike clay, stone vessels were not subject to impurity. Another unusual find was a fragment from a multi-spouted oil lamp. This fragment is especially interesting because it nicely illustrates how archaeologists reconstruct pottery from even a small piece (provided, of course, it is the right piece).

056

One thing we did not find is a plaque with an inscription reading, “You are now entering Archelais.”4 We made the identification, however, on the basis of several factors: First were geographical markers inferred from Josephus, the Jewish historian of the period, from Pliny the Elder, and from the Tabula Peutingeriana.

We were also helped by the famous Madaba map, a sixth-century mosaic map in a church in Madaba, Jordan. Archelais appears on the Madaba map at just about the location of our site and is pictured as a walled city with three towers with a gate between two of them. East of the city on the map is a tower constructed on top of an arch, with a ladder leaning against it. North of the tower is a palm tree and other plants (perhaps balsam). In general, this comports with what we found in our excavation.

We indeed discovered a monumental rectangular tower built of ashlars (squared stones) on a mound 15 feet above the settlement. In its earliest phase it guarded the agricultural estate associated with the mansion. The tower served not only as a watchtower but perhaps also as a residence (based on some of its architecture). The tower is almost as large as the mansion and is preserved in places to a height of nearly 20 feet. The sturdy walls of the tower are 4 feet thick. Traces of red paint on the white plaster can still be faintly seen. We did not find an entrance to the tower, so we assume that access was by means of a wooden ladder (as pictured in the Madaba map) or by a ramp leading directly to the first or second floor. There were at least ten rooms in the tower. The high quality and Greek architecture of the mansion were also evident in the tower. Architectural fragments included large stone voussoirs (wedge-shaped stones that support an arch or dome), column drums and a fragment of a cornice decorated with an egg-and-dart design and bearing a mason’s mark. The cornice was found in secondary use in another later Byzantine building, but we know it came from the tower because the ashlar stones in secondary use are the same size as those in the tower, and also because the cornice is in Roman rather than Byzantine style.

It seems that Archelaus built Archelais on a virgin site. We found no earlier remains in our excavation. This is in accord with the account in Josephus. In its earliest phase, it was an agricultural estate supported by date groves and sheep raising. Archelaus probably intended to expand the settlement but his short reign apparently frustrated this ambition.

When Archelaus was exiled to Gaul, Augustus gave Archelais to Herod’s sister Salome, who bequeathed it to Augustus’s wife Livia. In the excavations we found nothing that could be dated to the time when Salome and Livia were the owners of the estate (6–29 C.E.). From 29 to 41 C.E., the site was under the supervision of the Roman prefects, but again we found nothing from this period.

Following the Roman prefects, Herod’s grandson Agrippa I became ruler of this area (41–44 C.E.), and he continued the expansion of Archelais. New houses were built and, of special significance, a road station or road house was built for pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. The economy of date palms and sheep raising was now supplemented by road services.

The road station, sited on the top of a flat ridge, covered 4 acres. Remains of all four walls have been found. Rows of pilasters supported roofed stoas for 057protection from the sun. Pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem from the north (Galilee and Bashan) preferred to travel through the predominantly Jewish Jordan Valley rather than the mountains of Samaria, because of Samaritan hostility to Jews. When Jesus went from Judea to Galilee through Samaria, he stopped by a well and asked a Samaritan woman for a drink; she responded, “How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?” The text then adds, “Jews do not share things in common with Samaritans” (John 4:9). It seems that Jesus usually preferred the Jordan Valley route via Jericho instead of the unfriendly hills of Samaria (see Matthew 20:29). When he used this route, he would pass Archelais.

Inside the roadhouse was another mikveh, also with two pools and a connecting channel. Here, however, we were able to expose five steps to the bottom. The bottom step, as is often the case in mikva’ot, is particularly wide. I asked Ronny Reich, the expert on these ritual baths, why this was so, and he was not quite sure. Perhaps it was more comfortable for someone to sit during immersion. As Reich explained to me, sometimes an extra-wide tread is also found on a step in the middle of the stairs. Perhaps this was used to sit on when the water was higher in winter. In the summer, people purifying themselves in the mikveh would descend further, perhaps sitting on the bottom step.

Most of the coins we found in the excavation were minted during Agrippa’s short reign when the roadstation was in operation. The road station continued to function until the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.). The Jewish settlements in the Jordan Valley participated in the revolt—and paid dearly. Archelais was destroyed by Vespasian during his conquest of the Jericho region on his way to Jerusalem.

After the Roman conquest of the Jordan Valley, a Roman army camp occupied the slopes of the mountain range to the west, to guard the roads and prevent resettlement by Jews. The Roman soldiers at Archelais were probably connected with the Roman soldiers who occupied Qumran after it, too, had been destroyed.

During the second century C.E. the site was again occupied, this time as a pagan settlement. On a road leading from the settlement, a new inhabitant dropped his watch—well, not exactly a Rolex, but the top of a column drum shaped into a conical sundial. Its lower part features the figure of a bearded man lying on his side, probably Heracles. Under the figure, in a simple frame, is a damaged illegible inscription. The sundial dates to the second century C.E. and suggests the site’s pagan occupation, as do several Arabic names found in floor inscriptions in secondary use.

During the Byzantine period (fourth–sixth centuries), the local inhabitants converted to Christianity and built a typical basilical church for worship. The nave was entered through a columned 059narthex or porch. At the far end of the nave was the raised bema or platform (2 feet above the central nave floor) and, behind that, the apse enclosing the altar. The apse of the church was 20 feet wide and half as deep. The apse floor had been thrice covered with mosaics, reflecting separate phases of use. The lowest phase was simply a white mosaic. Above that was a colored mosaic with geometric designs. The top layer was even fancier, including a net of black and white squares with red corners, cross-shaped blossoms in red, geometric and floral motifs of interlaced circles, a diamond pattern and flower buds, as well as five mosaic dedicatory inscriptions in Greek; but no animals or human figures. It is not entirely clear why this is so. Other contemporaneous mosaic pavements in churches in Israel are decorated with animals and even humans.

Under the latest apse floor, we found a reliquary that undoubtedly once contained the bones of some revered church official. Another reliquary, this one of marble, was found beside the bema; on one side was carved a cross inside a circle.

A chancel screen separated the nave from the bema and apse. We recovered fragments of the chancel-screen posts, which were made of blackish limestone.

Each of two side aisles in the nave was created by a row of six columns. Most of the column bases were still there in situ. An interesting fragment of an architrave bears an egg and dart (ovolo) pattern. In addition, in one of the two side rooms of the church, we found a table suggesting its use in some unidentified religious ritual.

As might be expected, the fanciest inscription was in the apse, consisting of two amphoras on either side of a medallion made of two concentric circles with flower buds between them. In the middle of the medallion is a black cross. Four flower buds sprout between its arms. The inscription on the bema was dedicated to Abbosoubbos the priest, who (among others) was responsible for the mosaic paving of the floor. The inscription is dated to the 078fourth year of the indiction of the Emperor Flavius Justinus. Theoretically, this could be either Justin I, who ruled from 518 to 527, or Justin II, 565 to 578.

The fourth year of the indiction might have been either 525 or 570. But we prefer the later date because on paleographic grounds the inscription cannot be dated before the mid-sixth century.

Outside the church we found a stone cross that perhaps originally stood atop the church—at least that is where we put it in our reconstruction.

The church was abandoned in the late sixth century. Why, we do not know. Finally, it was burned in the Persian invasion of the early seventh century, marking the end of settlement at Archelais.

The inscriptions were translated from the Greek by Dr. Leah Di Signi of the Hebrew University.

Herod’s son Archelaus was hated by his Jewish subjects no less than his father. Herod had left instructions that on his death leading scholars were to be put to death to ensure that there would be mourning when he died. This gives some idea of the attitude of the people toward him.

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Ehud Netzer, “Floating in the Desert,” Archaeology Odyssey 02:01; Ehud Netzer, Barbara Burrell and Kathryn Gleason, “Uncovering Herod’s Seaside Palace,” BAR 19:03; Ehud Netzer and Zeev Weiss, “New Mosaic Art from Sepphoris,” BAR 18:06; Ehud Netzer, “The Last Days and Hours at Masada,” BAR 17:06; Ehud Netzer, “Jewish Rebels Dig Strategic Tunnel System,” BAR 14:04; Ehud Netzer, “Searching for Herod’s Tomb,” BAR 09:03; Ehud Netzer, “Herod’s Family Tomb in Jerusalem,” BAR 09:03; Ehud Netzer,

Endnotes

The excavations at Archelais (Khirbet el-Beiyudat) were carried out between 1986 and 1999 and were conducted on behalf of the staff officer of archaeology in Judea and Samaria and directed by the author.