In the fourth century B.C. a man named Antikrates from Knidos, on the southwest coast of Anatolia, was struck in the face by a spear. The spearhead lodged so deeply in his head that it could not be removed. He lost his vision and lived with the spearhead in his face.

Antikrates probably consulted doctors, magicians, priests, drug vendors and root-cutters—all of whom may have stirred up poultices and (except for the doctors) spoken charms over him.

Eventually, he decided to visit a Greek healing god named Asklepios. The god’s most famous sanctuary was at Epidauros on the east coast of the Peloponnesus. Although the journey across the Aegean Sea and the Greek mainland was perilous and would have taken several days, so great was Antikrates’s desire to be healed that he made the long trip.

Upon reaching Epidauros, Antikrates slept in the sanctuary, as was customary, and dreamed that Asklepios came and healed him. He awoke cured: The spearhead was gone and his vision restored.

Asklepios was the most popular healing god in all of antiquity. For more than a thousand years, people in search of cures flocked to his widespread sanctuaries—from Britain in the north to Libya in the south, and from Spain in the west to Iran in the east.1 Asklepios was sought by the hopeful, and desperate, throughout the known world.

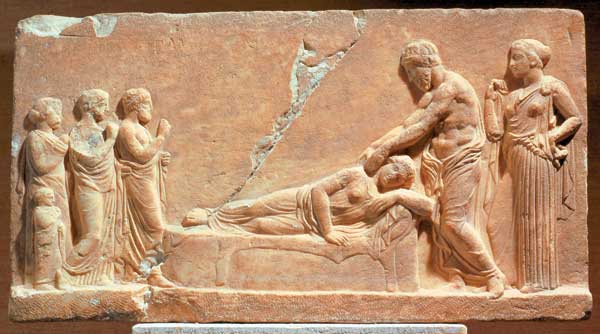

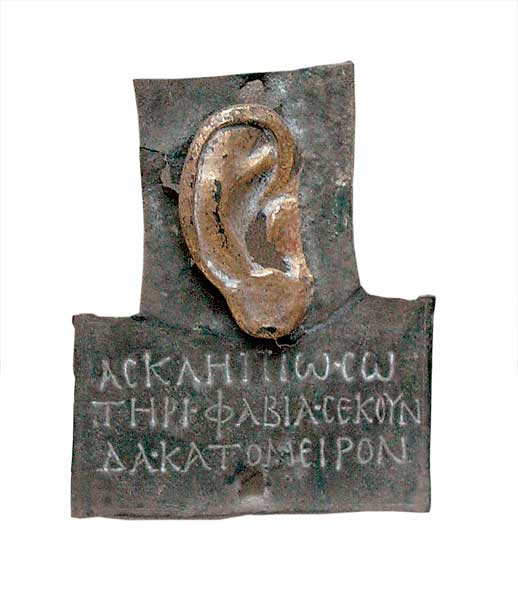

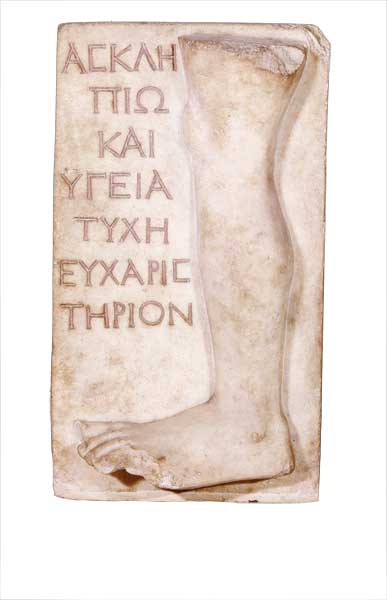

Like Antikrates, visitors often traveled long distances to these sanctuaries. On arrival, they made a sacrifice of food or animals, cleansed themselves, made a monetary offering and then went to a designated place in the sanctuary to sleep. They hoped that Asklepios would appear before them and heal them while they dreamed, a process known as incubation. If all went well, they awoke cured, made Asklepios an anatomical votive offering (a small statue of the body part that was healed) and set off for home.

At Epidauros, in a long, covered hall that may have been used for incubation, excavators have recovered tall marble slabs, or stelae, inscribed with the names, hometowns and ailments of people cured by Asklepios. These stelae also document the impressions of those who incubated. Here, for example, is the entry for our friend Antikrates:

Antikrates of Knidos, eyes. This man had been struck with a spear through both his eyes in some battle, and he became blind and carried the spearhead around with him inside his face. Sleeping here he saw a vision. It seemed to him that the god pulled out the dart and fitted the so-called “girls” [pupils] back into his eyelids. When day came he left well.2

The earliest reference to Asklepios comes in Homer’s Iliad. Here Asklepios is a mere mortal physician, renowned for his expertise in battle-wound management; he is “a man worth many men when it comes to cutting out arrows and sprinkling on soothing herbs” (Iliad 11.514-515). In later accounts, Asklepios is the god Apollo’s son and pushes his healing skills to new limits by raising the dead. For this he pays a hefty penalty: His grandfather, Zeus, hurls him into Hades with a thunderbolt (Zeus is never one to be outdone by his own children, and especially not his grandchildren). Apollo finally convinces Zeus to bring Asklepios back from Hades (thus allowing the king of the gods to re-appropriate the power of raising the dead), and Asklepios is eventually deified.3

Often depicted as a bearded man with a walking staff entwined by a serpent,a Asklepios appears on numerous coins, statues, mosaics, signet rings and medicine boxes. From both modern excavations and ancient inventory lists, we know of the massive volume of dedications to the god—such as anatomical votives, statues and sculpted reliefs—all attesting to his popularity.

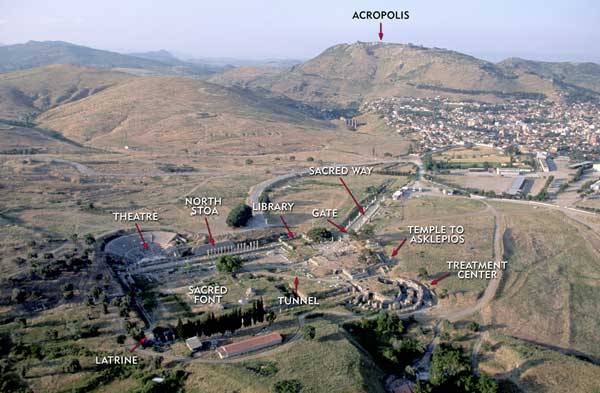

Although sanctuaries of Asklepios (Asklepions) varied in size, layout and composition, they all had several common elements. All Asklepions had a temple housing a statue of the god, as well as an altar where sacrifices were performed. (An altar separate from the temple was necessary in ancient Greek sanctuaries because worship focused on sacrifice and took place outside of temples. For the Greeks, a temple was the house of a god, and it often served as a vault for gifts to that god.) All Asklepions had a source of water, such as a well, for bathing and cleansing before incubation. And they all had areas designated for incubation—sometimes a room in a building, or just an open space outdoors.

The earliest sanctuary of Asklepios, at Epidauros, seems to have been in operation in the early fifth century B.C.4 The cult was soon known in Athens, as we know from references in the plays Alcestis by Euripides (c. 480–406 B.C.) and Wasps by Aristophanes (c. 448–388 B.C.). An inscription dated to 420 B.C.5 records the arrival of the cult in Athens.b By the fourth century, Asklepios had likely spread to more than 200 places; a hundred years later he had reached as far as Rome in the west and Pergamum in the east. The cult lasted well into the fifth century A.D., suggesting that it was tenacious in resisting Christian opposition to pagan practices.

The cult’s emergence in the fifth century B.C. and its rapid spread occurred alongside developments in Greek medicine that contributed to Asklepios’s popularity. Doctors are attested in Greece as early as the Bronze Age. The Greek word for doctor, iatros (from which we get words like “pediatrician”), appears in Bronze Age documents. Archaeologists have also found medical instruments, probably belonging to a doctor, in a Bronze Age tomb.c

The earliest evidence indicates that the tools and methods of Greek doctors remained largely unchanged for centuries. They used poultices of drugs and bandages to heal wounds; they performed surgery with scalpels and other knives; and they treated internal disorders with bell-shaped instruments, usually of bronze, which were heated and applied to the skin to create a vacuum.

The ancient Greeks believed that, to be healthy, the body’s fundamental substances, called the humors (in Greek, xumoi, or “juices”), had to be in balance. The principal humors were blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile; a person with too much phlegm, for example, might have a bad cough, and a person with too much bile might be angry or melancholic.6 This medical hypothesis is called the humoral theory, and it prevailed in western medicine until the 19th century (as we can see from the longstanding procedure of bleeding, meant to relieve the body of too much blood).

In their healing, doctors did not rely on prayer, incantations, amulets or any other devices intended to influence the divine. The reason for this is that doctors, unlike many or even most people, did not believe that the gods could make you sick. Many non-doctors, for example, thought that an epileptic seizure was caused by a god’s taking hold of a person and shaking him, a tradition evident today in our word “epilepsy,” from the ancient Greek meaning “to seize upon.”7

The fifth century proved a watershed in Greek medicine. The earliest surviving medical treatises date to this time, as does the most famous physician of antiquity: Hippocrates. So great was his influence that scholars later in antiquity attributed over 60 treatises to him, though it is clear from their style and content that many are not by Hippocrates.8

These treatises indicate that doctors in the fifth century were taking radical steps to further professionalize their techne, or craft. What had been a trade handed down from father to son, true of most professions in antiquity, was now being opened to outsiders. For a fee, you could apprentice yourself to an established physician.

The opening of the medical profession threatened its credibility. In the absence of licensure, there was no simple way for a doctor to prove that he was adequately trained and a good practitioner. Since dead or unimproved patients do not attract business, the best way for doctors to maintain and even increase credibility was to refuse to take on cases they thought incurable. Some ailments were deemed inherently incurable; others had progressed too far to be curable. “In cases where we have control due to our skill or to nature, there we can be craftsmen, but not otherwise,” claims the author of one fifth-century B.C. Hippocratic treatise.9

Patients turned away by doctors looked for alternatives. Asklepios attracted their attention because he was a deified doctor. Just about every god in antiquity had the power to heal and was worshiped as a healer, but no others concentrated exclusively on healing, and few ever used any method characteristic of doctors. Most gods healed by touch, proximity or, like Athena in the Iliad, who heals Diomedes of an arrow wound (Iliad 5.114-122), by mere will. Thus if someone needed a doctor but no mortal doctor could help, then perhaps that person would turn to the doctor-god Asklepios.

If early on Asklepios had been left with only the sickest patients in need of magical cures, by the fifth century B.C. he had become, because of his broad popularity, the divine patron of the medical profession. Doctors claimed descent from Asklepios and swore the so-called Hippocratic oath in the name of Asklepios, among other gods.10 Doctors and Asklepios maintained a close affinity throughout antiquity: Doctors served as priests of Asklepios, dedicated statues and medical instruments to him, and toted his image around on their medical kits. A doctor named Nikias offered frankincense every day before a statue of his patron god.11

Even in popular culture, medicine and Asklepios were closely conjoined. Stories circulated, for example, that Hippocrates learned medicine by writing down cures posted at Asklepios’s sanctuary.12 Hippocrates’s hometown of Kos (a city on the island of the same name just off the southwestern coast of Anatolia) later became home to one of the most lavish sanctuaries of Asklepios. A wealthy doctor named Xenophanes funded large building projects at the Kos sanctuary. Galen, a prominent physician of the second century A.D., grew up near the great sanctuary of Asklepios at Pergamum and claimed to have entered the medical profession at Asklepios’s urging and to have been himself healed by the god.

The relationship between doctors and Asklepios was complementary in many respects, including the use of specific instruments and methods of healing. In the early period of the cult, those who incubated described Asklepios as performing surgery (like cutting open and sewing up the abdomen), excising sores, grinding and applying drugs, and rebalancing fluids. Being a god, Asklepios often took these measures to superhuman extremes, as indicated by the following healing inscription from Epidauros:

Arata of Laconia, dropsy. Her mother slept here on behalf of her daughter who remained in Lacedaimon, and she saw a dream. It seemed that the god cut off her daughter’s head and hung her body with the neck toward the ground. When a lot of fluid had run out, he untied her body and put her head back on her neck. After she saw this dream, she returned to Lacedaimon and found that her daughter was healthy and had seen the same dream.13

Unlike Asklepios, doctors never decapitated their patients, but they did perform surgery and they did rebalance humors, which is essentially what Asklepios is doing in this case.14

Sometimes Asklepios got help from sacred animals, especially snakes, left to wander freely in his sanctuaries. There are several instances of people being bitten or licked by dogs and geese in addition to snakes. Even in these instances, one can often detect a Hippocratic theory lurking, such as a snake’s biting the tumor on a girl’s finger, thereby draining and healing it.

Aristophanes’s comedy Ploutos (Wealth), produced in Athens in 388 B.C., includes a delightful vignette of Asklepios’s methods. The god Wealth has gone blind and is no longer distributing riches fairly, so a poor wretch looking to rebalance the inequity takes him to Asklepios for a cure. There he incubates along with Wealth and witnesses the following:

Now, first of all Asklepios turned to Neokleides [another blind visitor]

And started to grind ingredients for a poultice.

He put three heads of garlic in his mortar

Then mixed in fig-juice rennet, and squill as well.

Next, once he’d soaked it all in acrid vinegar,

He turned the eyelids out and smeared them both

To make them sting the more …

After that he went and sat down next to Wealth.

The first thing he did was touch his head,

Then picking up a piece of spotless linen

He wiped it round his eyelids. Panakeia [Asklepios’s daughter]

Wrapped round his head and right around his face

A purple cloth. The god then clicked his tongue,

And from the temple slid a pair of snakes

Immense in size …

They both slipped silently beneath the cloth

And licked his eyelids round, it seemed to me.

And sooner than you’d drink a gallon of wine,

My mistress, Wealth stood up, his sight restored!15

What exactly happened to those who incubated in Asklepios’s sanctuaries is unknown. There is no evidence that doctors practiced in these sanctuaries. Some scholars have suggested that priests performed the cures; others argue that the mere power of suggestion had a healing effect. We may never know. But it is striking that those cured envisioned the god functioning much like a doctor. He was, simply put, a super-doctor.

As time went by, Asklepios moved away from immediate cures to prescribing complex regimens of diet, drugs and even fitness. A healing inscription from Asklepios’s sanctuary in Rome describes the following cure:

The god advised Valerius Aper, a blind soldier, to go and take the blood of a white rooster along with honey and to blend them into a salve and to apply this to his eyes for three days. He saw again and went on his way and offered thanks to the god publicly.16

And Epidauros records the treatment of one Marcus Julius Apellas, who was suffering from dyspepsia:

[Asklepios] told me to keep my head covered for two days … to eat cheese and bread, celery with lettuce, and to wash myself without assistance, to exercise by running, to eat lemon peels … to go for a walk in the upper portico, to do some light exercises, to sprinkle myself with sand, to walk barefoot … and to drink milk without honey.17

Many of the god’s larger sanctuaries, like Epiduaros, had running tracks, gymnasia and bathing facilities to support prescribed regimens.

Medical treatises indicate a similar interest in holistic cures that take into account one’s environment and diet. Such external factors could affect humoral balance. For example, counter to the common belief that epilepsy was caused by the gods, some doctors thought epilepsy was caused by an excess of phlegm. These doctors said that an epileptic seizure occurred when the heat of the sun or the south wind melted phlegm in the head, which then flowed down into the veins that carry pneuma, or air, until the phlegm cooled and thickened and thus stopped the flow of air, causing a person to thrash as if suffocating. How to avoid seizures if you are phlegmatic? Consume foods that produce dryness and, if possible, avoid drastic changes in temperature.18

Asklepios often treated ailments like blindness, deafness, baldness, paralysis, infertility, unusually long pregnancies, lice, gout and festering wounds. None of these is typically fatal, but all are recurring, or lingering, and difficult to treat. Some are still beyond the reach of doctors today.

Ancient healing accounts emphasize the amount of time illnesses lasted before Asklepios treated them. A woman was pregnant for five years, another for three; a man had a spear lodged in his jaw for six years; another had an arrow festering in his lung for a year and a half and filled an astounding 67 bowls with pus.

Nor was Asklepios running a charitable institution. People visiting his sanctuaries had to bring animals for sacrifice, offer money, dedicate plaques or anatomical votives, and even finance a journey that took them away from their farms or other means of livelihood for days or even weeks. The poorest of the poor lacked the resources to get to the god’s sanctuaries, much less to make the requisite offerings.

Yet Asklepios remained one of the most popular healers of the Greco-Roman world. His cult at Pergamum reached its peak in the second century A.D., and incubation was still being practiced at his sanctuary in Athens as late as the fifth century.

Asklepios trafficked in one of humankind’s most valuable commodities: health. As Herophilos of Keos wrote around 300 B.C.: “Wisdom cannot display itself and art is not evident and strength unexerted and wealth useless and speech powerless in the absence of health.” At a time when effective healing was hard to come by, Asklepios offered hope and relief to countless people across the ancient Mediterranean.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

1.

Asklepios’s serpent-entwined staff (the caduceus) is even today a symbol of healing and medicine all over the world.

2.

According to Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, the last words spoken by Socrates (469–399 B.C.) were, “Crito, I owe a cock to Asklepios; will you remember to pay the debt?”

3.

This Mycenaean tomb, dating to 1450 B.C., is discussed in Robert Arnott, “Healing and Medicine in the Aegean Bronze Age,” Historical Review 89 (1996), pp. 265–270.

Endnotes

1.

The best general study of the cult remains Ludwig and Emma J. Edelstein, Asclepius (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1945; reprinted 1998).

2.

The stelae are compiled and translated by Lynn LiDonnici, The Epidaurian Miracle Inscriptions (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995). The tale of Antikrates appears as B12 in LiDonnici’s numbering system.

3.

See, for example, the Alcestis of Euripides and Pindar’s third Pythian ode.

4.

For the sanctuary at Epidauros, see Richard Allen Tomlinson, Epidauros (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1983.)

5.

A portion of this inscription is recounted in Edelstein, Asclepius, vol. 1, Testimony 720.

6.

For a general introduction to Greek medicine, see H. King, Greek and Roman Medicine (Bristol Classical Press, 2002).

7.

The traditional view of epilepsy as caused by the gods is described in the Hippocratic treatise On the Sacred Disease.

8.

For information on Hippocrates and the Hippocratic corpus, see Jacques Jouanna, Hippocrates (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1999).

9.

On Art 8.12.

10.

On the relationship between doctors and Asklepios, see Owesi Temkin, Hippocrates in the World of Pagans and Christians (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1991), esp. ch. 14.

11.

Theocritus, Epigram 8.

12.

Pliny, Natural History 29.

13.

LiDonnici B1 (see note 2). Incubation by proxy was highly unusual.

14.

When doctors treated dropsy, which they thought was an accumulation of water, they recommended dry and acrid foods so that the patient would pass more water and thus rebalance the body’s fluids. This is prescribed in the Hippocratic treatise Regimen in Acute Diseases, 20.

15.

Aristophanes, Wealth, trans. Stephen Halliwell, in Aristophanes: Birds, Lysistrata, Assembly-Women, Wealth (Clarendon Press, 1991), ll. 716–738.

16.

Recounted in Edelstein, Asclepius, vol. 1, Testimony 428.

17.

Recounted in Edelstein, Asclepius, vol. 1, Testimony 432.

18.

Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease.