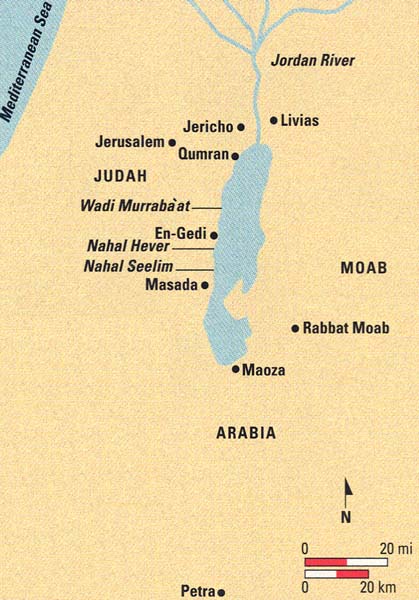

The column of Roman soldiers marched slowly south along the western shore of the Dead Sea toward En-Gedi, one of the region’s major governmental and commercial centers and a stronghold of Simon Bar Kosiba,a leader of the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. Two years earlier, in 132 C.E., Bar Kosiba had expelled from the city the Roman officials and the unit of the Roman army stationed there, the First Thracian Military Cohort. Now, after numerous skirmishes and running battles, the Roman army had pushed Bar Kosiba’s rebels out of Jericho (about 30 miles to En-Gedi’s north) and the Thracian cohort, with the aid of other Roman army units, was about to retake En-Gedi.

As he marched along with his troops, the cohort’s leader, Centurion Magonius Valens, remembered the old friends he once had in En-Gedi. He had socialized with the city’s leading families, including Elazar Khthousion and his son Judah, who owned the courtyard next to the Roman camp. He had even done business with them ten years earlier, lending them 60 denarii of Tyrian silver at a good profit.1 Valens knew Judah had died before the war broke out, but some of his other friends might still be in the city. Perhaps he would meet Judah’s second wife—Babatha daughter of Simon.

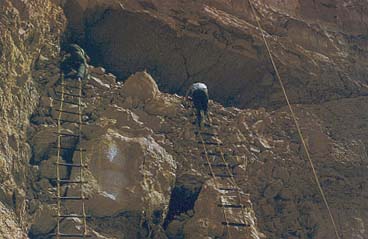

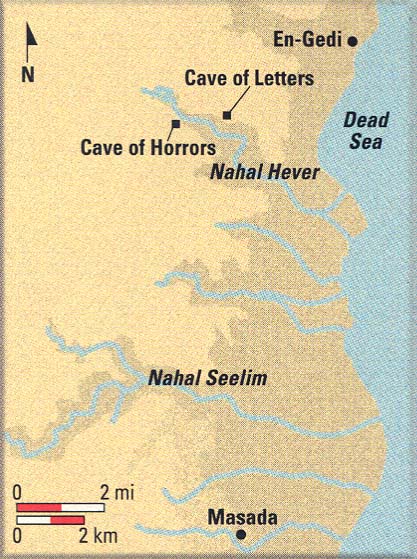

As the Romans approached, however, Babatha, her husband’s family and other leading citizens of En-Gedi fled into the Judean desert. Weeks before, they had stored supplies in caves high in the walls of Nahal Hever, a wadi, or dried riverbed, three miles south of En-Gedi. Now they gathered a few belongings and joined other Bar Kosiba supporters and war refugees heading for the Judean desert caves. Babatha’s group climbed a narrow path to Nahal Hever’s top on the wadi’s north side and then down the escarpment into a cave. Another group climbed the other side of the wadi to a cave in the south wall. There they hoped to wait out the Roman invasion.

Today, the outlines of Roman army camps on the plateaus above each of these caves, positioned to cut off escape, testify to the failure of their plan. The cave in the southern wall, excavated in the early 1950s and 1960s, contained the bones of dozens of men, women and children who had starved to death while the Romans kept watch above. Archaeologists named this cave the Cave of Horrors.2

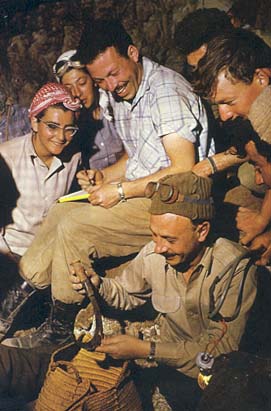

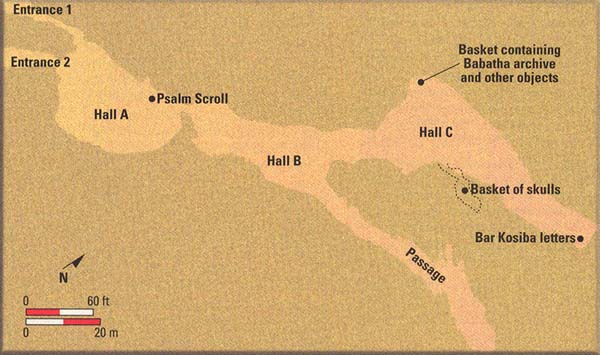

Babatha’s cave, excavated in the early 1960s, also contained bones, but it held many hidden documents too. Some belonged to Babatha, some to lieutenants of Bar Kosiba. Archaeologists named this cave the Cave of Letters.

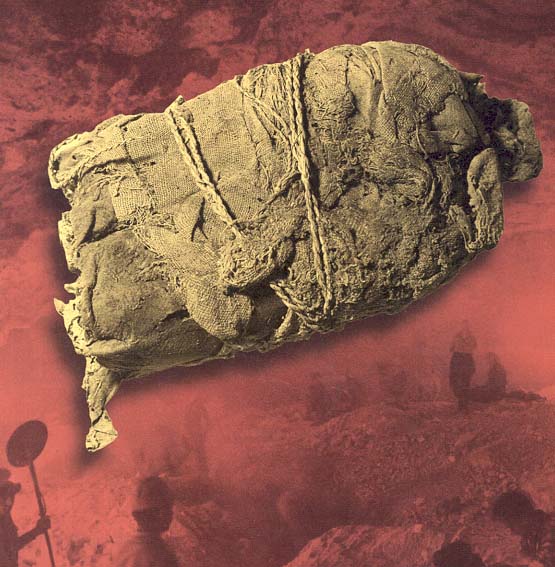

Babatha had expected to survive the Roman danger, so she had carried to the cave carefully packaged documents (the contents of her safety deposit box, as it were) to protect her rights to her properties, contracts and money. Her papers record legal suits over payments and property, the guardianship of her minor son, petitions to the court, marriages, summons, leases and deeds. Sometime near the end of her stay in the cave, she placed these documents in a crevice between two rocks in the cave’s side. She also hid a beautiful jewelry box, bowls and knives, a frying pan, a mirror, clothing, sandals, cloth and jugs. Then she disguised the crevice’s mouth by sliding an upright stone into it. Clearly, she hoped to return to retrieve her belongings.

Who was Babatha? According to her documents, she was the daughter of Simon from the village of Maoza (mahoza, in Aramaic, means “harbor”) in the district of Zoara on the southern shore of the Dead Sea, which was in the Roman province of Arabia (established in 106 C.E.). Though we do not know the year of her birth, by 124 C.E. Babatha was a young widow with a son, Jesus son of Jesus, for whom two guardians were appointed.3 In 128 C.E. she married a second time, to Judah son of Elazar Khthousion, of En-Gedi, then residing in Maoza.4 Judah already had a wife—Miriam daughter of Beianos, of En-Gedi—and a daughter, Shelamzion. Judah died in about 130 C.E., a few years after marrying Babatha. Little is documented of her life after that. The latest document in her archive, a court receipt, dates to 132 C.E., at the beginning of the Bar Kosiba war against Rome. Her earliest document, which records a dowry settlement in Aramaic, dates to 94 C.E.

The Babatha archive, as her recently published documents are called, provides a narrow but fascinating window into the culture and the ethos of the people in the villages and cities in and around the land of Israel during the early second century C.E.

Most of the documents in her archive record legal matters. They show that Babatha, her family and the network of families that she did business with were in contact with the Roman provincial courts in Rabbat Moab and Petra. She and her associates petitioned and appeared before the Roman governor and other officials to settle their various affairs. The names and places and types of transactions recorded in her documents are similar to those in documents found in caves in Wadi Murabba‘at, further north along the shore of the Dead Sea.b In both sets of documents, property lines are precisely described in relation to neighboring owners’ lands. The changes in ownership testify to carefully recorded property transfers over the course of years. If Babatha wished to claim her property in Roman or Jewish courts after the war, she had to preserve her documents. Her wealth in land, loans and inheritances was guaranteed by her papers.

Babatha’s documents refer to date-palm orchards, houses, courtyards, a trust fund of 400 denarii, a loan of 500 denarii, and other loans, deposits and contracts. The cave where the archive was found also contained expensive clothes and personal items, such as cosmetics and utensils. These items of luxury contradict the common belief that the Dead Sea area was barren, inhabited only by austere sectarians such as those at Qumran 60 years earlier. Babatha’s and Judah’s families were probably typical of the more prosperous residents of the area.

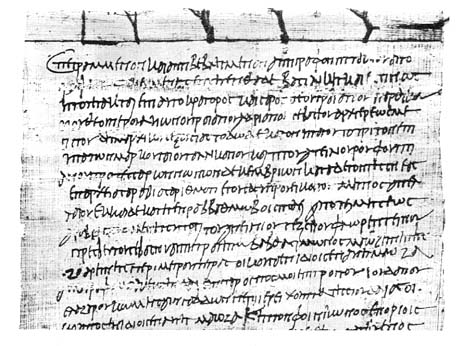

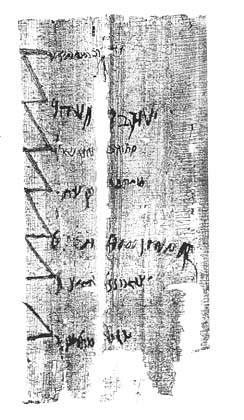

Of the 35 documents in Babatha’s archive, 26 are written in Greek, six are written in Nabatean (a dialect of Aramaic spoken mainly in the area southeast of the Dead Sea), and three are written in Aramaic (the Jewish vernacular of the time).

The Greek documents have been published in their entirety as a book. They bear the signatures of people with traditional Jewish, Nabatean,c Roman and Greek names. One of Babatha’s loan documents is signed by Kallaios son of John, Simon son of Simon, Gaius Julius Proclus, Onesimos, Theodore, Joseph and John.5 Every name but Simon’s is Greek. Simon, Jesus, Elazar, Judah, Shelamzion and Miriam are among the Jewish names that appear in her Greek documents. Others are a combination of Jewish and Greek names, such as Elazar Khthousion and Judah Cimber, in accordance with long-standing custom.6 Nabatean names, such as Abdereus son of Soumaios, ‘Abd’obdath son of Shuheiru, and Nubi son of Walat, are listed among the witnesses of the Petra council extract that appointed two guardians for Babatha’s son. The two guardians are ‘Abdobdas son of Illouthas, whose name is Nabatean, and John son of Eglas, whose name is Jewish.7 A judicial summons written in Maoza is witnessed in Aramaic by Elazar son of Shim’on and by Yehosef and Elazar, sons of Mattat; it is also witnessed in Greek by Thaddeus son of Thaddeus.8 When Babatha sold a date crop in Maoza to Simon son of Jesus, she had a Nabatean, Yohana son of Makhoutha, as her mandatory legal guardian for the transaction.9 In general, Babatha’s documents indicate that Jews and non-Jews transacted business together.

In the Greek documents, only one person, Babatha’s young son, Jesus, is identified as a Jew (Ioudaios in Greek): “Jesus, a Jew, son of Jesus of the village of Maoza.”10 The Greek term Ioudaios, from which the English “Jew” derives, is often used to describe an inhabitant of Judea, someone commonly recognized as a Jew or someone who lives according to Jewish customs.11 Since here the child is from Maoza, not Judea,12 he is clearly being identified by his heritage and by his family’s way of life. But why is he identified as a Jew in an official document when none of the other Jews involved are so identified?

Ross Kraemer, an expert in early Judaism, has noted that the identifying epithet “Jew” appears relatively seldom in Jewish inscriptions, including funerary and dedicatory synagogue inscriptions.13 In one inscription the deceased, either a three-year-old deceased foster daughter or her mother, is identified as a Jew (Eioudea).14 In another a deceased 18-year-old woman is designated Iudeae in Latin by her mother.15 Kraemer has suggested that people are called Jews in such inscriptions because their Jewishness is not obvious—if, for example, they are proselytes (converts to Judaism), or gentiles who observe Jewish customs, or people from non-Jewish families. Or “Jew” in its various Greek and Latin forms may have been a proper name.16 All these suggestions are hypothetical and indicate the lack of clarity in the meaning of the simple term “Jew.”

Babatha’s son, Jesus, is the son of two Jews, so he is not a proselyte. He is not from Judea, and he and all the other people in this document are mentioned by name and by parent’s name, so Ioudaios is almost certainly not being used here as a name. He must have been very young because the documents concerning his guardianship stretch over eight years, from 124 C.E. to 132 C.E. Since the document that identifies him as a Jew is an extract from the minutes (Latin, acta) of the town council (Latin, boule) of Petra, a Nabatean city and the capital of the Roman province of Arabia, perhaps the identification of ethnic origin was made on his behalf because he was not old enough to have established his group membership by his own customs, language and actions. Even so, sharp Jewish community boundaries apparently did not exist, as one of the two guardians appointed to him in this document is a Nabatean.

In Babatha’s documents adult Jews are not identified as such by the word “Jew.” They have recognizably Jewish names and presumably act and worship in Jewish ways, but they also act as citizens of the Roman province and as residents of their villages. Babatha’s documents do not reveal specific communal or religious customs or affiliations that would differentiate Jews from other residents of the Dead Sea area. People are identified primarily by their place of birth, and they retain connections to that place even when they reside elsewhere. Babatha’s second husband was living in Maoza when she married him, but he was still identified as being from En-Gedi.

What can we learn from the formal elements of the documents in Babatha’s archive? Many are in Greek because that was the official language of the Roman province of Arabia and of the registries where transactions and legal decisions were recorded. Some are in Aramaic because it was the first language of the area’s Jewish residents. Others are in Nabatean because it was the dialect of Aramaic used by the Arab residents of the southern and western regions around the Dead Sea.

The Greek documents were written by scribes, some of whom were not very proficient in Greek grammar.17 These documents show that Roman legal forms were already in use a mere few decades after the Roman province of Arabia was formed in 106 C.E. The Roman governor apparently traveled to different cities and towns to hold official court sessions, each called a conventus in Latin and referred to individually in these Greek documents as a parousia.18

Jews clearly used the prevailing legal forms and institutions to make and litigate contracts with other residents of the province. Several of the Greek documents contain formal questions and answers concerning the validity of a transaction,19 following the form of a Roman legal document called a stipulatio in Latin. The ancient translation of Babatha’s subscription to her inventory and the registration of her land includes her oath to its accuracy, sworn by the tuche (the spirit, good fortune, protective deity [Latin, genius]) of Lord Caesar, in good Roman fashion.20 Babatha’s original Aramaic subscription, which was in the official document submitted to the government, was not included in her personal copy, so we do not know what was written for her in Aramaic. We should not assume, however, that she would have avoided such idolatrous expressions as swearing by Caesar’s tuche. Kraemer has cited Latin Jewish inscriptions containing invocations to gods such as Dis Manibus (the gods of the lower world) and Iunonibus (the Juneans, referring perhaps to goddesses associated with Juno). Some Jews may have felt comfortable using conventional references to the gods without implying any commitment to their worship.21

Babatha’s documents concerning her son’s guardianship also show the influence of Roman law.22 According to Roman law, Babatha could not serve as her son’s guardian, so the city council of Petra appointed two male guardians in 124 C.E.23 Jewish law would have allowed her to be her son’s guardian if her husband had appointed her, but he hadn’t.24 Babatha was not helpless, however. She used Roman law to its full extent to protect her son. According to Roman law, a mother could take legal action if her child’s guardians were not fulfilling their obligations. Four months after the two guardians had been appointed, Babatha petitioned the Roman governor with the complaint that her son’s guardians were providing an inadequate monthly stipend (only two denarii) for his maintenance.25 The next year (125 C.E.) she summoned the guardians to court26 and requested permission to administer the trust funds herself, offering to post security as a guarantee of her reliability, in an effort to provide three times the amount for her son.27 Essentially, she sought to become de facto guardian. The documents do not tell us how her case turned out, but the last document, the court receipt from 132 C.E., shows that seven years later she was still receiving two denarii a month from one of the guardians.28

Her documents, and similar ones, reveal the influence of Greek norms as well. In two Greek marriage contracts, one from Babatha’s archive and one from another archive found in the Cave of Letters, the husbands commit to clothing and feeding their wives and children according to Greek “custom” (nomo)29 or Greek “custom and manner” (nomo kai tropo).30 In Babatha’s own Aramaic marriage contract, however, Judah marries her “according to the law of Moses and the Jews” (yhwd’y).31 Similarly, in an Aramaic marriage contract from Wadi Murabba‘at dating approximately to 117 C.E., the son of a man named Manasseh takes a wife “according to the law of Moses” (kedin Moshe).32

Both Greek and Aramaic forms seem to have been used interchangeably by Jews around the Dead Sea area, perhaps with the same general meaning.33 Interestingly, we know of no Greek “custom and manner” of maintaining one’s family. For example, the other Greek marriage contract from the Cave of Letters34 provides for the support of the wife and children if the husband dies. This provision is found not in Greek law, however, but in Jewish law. So even if the contract says “according to Greek custom,” Jewish customs are being followed by Jews who make contracts in Greek. Most probably, in this and other matters of law the villagers followed prevailing local custom, which was called the “law of Moses” in Hebrew and Aramaic and “Greek custom” in Greek.35

The use of Greek and Roman forms and courts does not mean that the Jewish residents of the Dead Sea basin were cut off from Jewish law, only that they were influenced by a variety of local practices, customs and laws. Clearly, Babatha and her friends were not influenced by the early rabbis, who promoted an all-encompassing halakhicd system. Babatha’s documents contain no religious language beyond the perfunctory and conventional, such as the reference to Caesar’s tuche.36 The Mishnaice and talmudicf halakhic system, which stressed obedience to divine commandments and contained elaborate discussions of what was forbidden and permitted, is not referred to. Yet Babatha’s documents exhibit similarities with the Mishnah. Apparently, traditional Jewish law, customs and local practices existed alongside imperial law, and the social and legal practices and understandings evidenced in Babatha’s documents contributed to the highly articulated Mishnaic synthesis later on. For example, Babatha’s Aramaic marriage contract had a provision that if her husband Judah died she could continue to live in his house and be supported by his heirs. She could be sent away only if Judah’s heirs returned her dowry to her in exchange for the marriage contract.37 This is one of two competing practices recorded in the Mishnah.38 Babatha’s contract follows the Judean practice because Judah came from En-Gedi, part of Judea.39 (Other provisions of the Aramaic and Greek marriage documents also derived from Jewish law were later enshrined and discussed in the Mishnah.)

The network of social and marital relationships revealed in Babatha’s relatively few documents stretched around the Dead Sea and spanned Judea and the new Roman province of Arabia.40 Shelamzion, Babatha’s stepdaughter, residing in Maoza with her father and Babatha, was married to Judah Cimber, a man from En-Gedi, Shelamzion’s town of origin.41 Another woman from Maoza, Salome Komaise, was married to Jesus son of Menahem, from the village of Soffathe in the district of Livias, a city across the Jordan from Jericho.42

Babatha’s documents do not distinguish among or polemicize against rival social groups. The signatories and principals apparently interacted easily with all who lived in their area—Nabatean, Roman, Greek or Jew. The tensions with gentiles and the polemics against idolaters that we see in some Jewish literature do not appear here. Neither the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 C.E., nor the Bar Kosiba Revolt 60 years later (132–135 C.E.), nor the apocalyptic hopes of some groups who supported Bar Kosiba as Messiah, nor the reconstructive efforts of the early rabbis receive any notice. Instead, these admittedly limited and narrowly focused documents show prosperous Jews living in peace with their neighbors, following traditional Jewish and local ways of life and cooperating with the government without reflection or worry about the ethnic, theological or religious problems recorded in rabbinic and Greco-Roman literature.

The Babatha archive leaves us ignorant about many things, but it does suggest a context for Jewish life in the second century C.E. Jews lived side by side with many different peoples under the imperial authorities. Arguments about how Jewish a region was seem irrelevant in the face of these documents. Independent, self-contained ethnic groups unrelated to their surroundings are a scholar’s fantasy. The social and political world these people lived in was Greco-Roman and local at the same time. Jews married Jews but lived as residents of their home villages. They did business with a variety of people, using traditional contractual documents that had been adapted to Roman legal procedures and forms. Marriage contracts could be in Aramaic or Greek and might include elements of Jewish, Greek and Roman law.43 Residents of En-Gedi and Maoza conducted business in Greek as easily as in Aramaic and invoked Greek custom and Roman law as naturally as they did Jewish law.44 Interpretations of the Mishnah and Talmud that picture Jewish life in the second century C.E. as separate, independent and self-defining do not accord with what we see here, and the view they imply probably needs revision. The noticeable absence of the rabbinic system from these documents accords well both with the general tendency of Jews in the Roman period to follow the laws of the lands they lived in45 and with the slow spread of rabbinic influence and power among Jewish communities.

The Babatha archive does not tell us what happened to Babatha. Several letters from Bar Kosiba to the governors he appointed in En-Gedi—Jonathan and Masabbala—were found in the Cave of Letters. Written in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek, these letters indicate that Bar Kosiba actively gathered supplies and oversaw civic affairs in En-Gedi during the four years of his rule. The letters also testify to the difficulty Bar Kosiba had getting supplies and to the indifference of the people of En-Gedi—including Jonathan and Masabbala in some circumstances—toward him.46 Whether Babatha moved to En-Gedi as a supporter of Bar Kosiba or fled from Maoza because of some threat against the Jews we do not know.

Nor is Babatha’s end clear. The cave could have held many people, but the bones of only seventeen were found there—eight women, six children and three men. Their skulls, lacking jawbones, were interred in a basket in a narrow crevice in one of the cave’s chambers. The rest of their bones were wrapped in mats and placed in baskets nearby. This treatment of their bones indicates that they probably died in the cave and were interred much later by relatives.

Was Babatha among the dead? Or did she and others surrender to the Romans above and face execution or slavery? Whatever happened, she never retrieved her documents.

Those unclaimed documents have given Babatha a voice denied to many more prominent Jews. No documents from the Pharisees and Sadducees of the Second Temple period or from the Zealots of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.) have survived. But Babatha’s life, struggles and concerns survive in the fragile papyrus writings she so carefully wrapped and hid in the Cave of Letters more than 18 centuries ago.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

He is also known as Bar-Kokhba, but letters to and from him found in the 1960s indicate that his name was more likely to have been Bar Kosiba.

See Tal Ilan’s article, “How Women Differed,” in this issue.

Nabatea was the area located south and east of the Dead Sea and the Jordan River and settled by Arabs from northwest Arabia from the sixth century B.C.E. on. These Arabs gradually adopted a dialect of Aramaic (now called Nabatean) as their language.

The Talmud is the record of Jewish law consisting of the Mishnah and the Gemara (a commentary on and supplement to the Mishnah). There are two Talmuds—the Babylonian Talmud and the Palestinian (or Jerusalem) Talmud. Originally transmitted as oral law, both Talmuds were written down between 200 and 500 C.E.

Endnotes

See “Greek Papyri,” Naphtali Lewis, ed., in The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters, Judean Desert Studies (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989), P. (Papyrus) Yadin 11, pp. 41–46 (all citations of P. Yadin herein refer to this volume unless otherwise indicated).

For a popular account of the discoveries in the caves, see Yigael Yadin, Bar-Kokhba (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971). The complete report on the finds from the Cave of Letters (excluding the documents) is in Yadin, Finds from the Bar-Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters (Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963). Preliminary reports on other caves are in various articles in the Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ) published between 1961 and 1962.

P. Yadin 11 and P. Yadin 37, pp. 41–46, 130–133. John Hyrcanus and Alexander Jannaeus are perhaps the most famous Jewish leaders with double names.

In a much earlier Aramaic divorce document (Mur 19), the man leaves the woman free to marry a gever jehudi. This document was published in Pierre Benoit, J.T. Milik and Roland de Vaux, Les Grottes de Murabba‘ât: Textes, Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961). Documents from this find are identified by the abbreviation “Mur” plus the number assigned to them on the official excavation list. (They were numbered in the order they were found.) Also appearing in Joseph Fitzmyer, A Manual of Palestinian Aramaic Texts (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1978), no. 40, pp. 138–141, this document dates to the sixth year either of the First Jewish Revolt, thus 71–72 C.E., or more likely, of the existence of the Roman province of Arabia, thus 112 C.E.

In the Ptolemaic period in Egypt, the Greek rulers used terms like “Jew” and “Macedonian” to label the definitive geographical and ethnic origin of a person’s ancestors and to mark certain people as superior in status to native Egyptians, who were identified by their villages (Joseph Mélèze Modrzejewski, The Jews of Egypt from Ramses II to Emperor Hadrian [Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1995], pp. 80–81). However, this usage of Ioudaios is not pertinent here because the Romans abolished such distinctions (pp. 161–165). Jews, Nabateans and other inhabitants of the Dead Sea area were afterward identified by villages.

Ross S. Kraemer, “On the Meaning of the Term ‘Jew’ in Greco-Roman Inscriptions,” Harvard Theological Review 82 (1989), pp. 37–38.

Kraemer, “Inscriptions,” pp. 38–41. The inscription also uses the epithets “proselyte” and “Israelite,” but it is unclear which epithets refer to which people.

Babatha’s Aramaic marriage contract was written by her husband, Judah, who also wrote parts of her other Aramaic documents. See Yadin, Jonas C. Greenfield and Ada Yardeni, “Babatha’s Ketubba,” IEJ 44 (1994), p. 76.

Hannah Cotton, “Guardianship of Jesus Son of Babatha: Roman and Local Law in the Province of Arabia,” Journal of Roman Studies 83 (1993), pp. 94–108, esp. 102–107.

The contract (P. Yadin 10) has been published with commentary in Yadin, Greenfield and Yardeni, “Babatha’s Ketubba.” Just a few phrases and a brief description of the contract are given in the original publication by Yadin, “Expedition D,” IEJ 12 (1962), pp. 244–245. Later Mishnaic law bears some similarities to these early-second-century C.E. marriage contracts, showing both the variety and continuity of Jewish practices. For example, “according to the law of Moses and the Jews” in Babatha’s documents later became “according to the law of Moses and Israel” in Ketubot 26. Hayim Lapin (“Early Rabbinic Civil Law and the Literature of the Second Temple Period,” Jewish Studies Quarterly 2 [1995], p. 171, n. 67) suggests that the Greek equivalent of the Aramaic “according to the law of Moses and the Jews” is in lines 7 and 39 of the Greek marriage contract (P. Yadin 18). There the father, Judah son of Elazar, gives his daughter Shelamzion to Judah Cimber “for the partnership of marriage according to the laws (nomous).” Even if Lapin is correct, “the laws” governing the marriage are amorphous enough or accepted and understood well enough not to require specification.

The end of the line in Mur 20 (Benoit, Milik and de Vaux, Murabba’ât; Fitzmyer, Manual, no. 41, pp. 140–143) is missing, so the full phrase may have been “according to the law of Moses and the Jews.”

The suggestion that the marriage contracts of the younger generation (Judah’s daughter Shelamzion in P. Yadin 18 and Salome in P. Yadin 37), which were in Greek, bespeak a social trend toward gentile ways is very doubtful. See Lewis, Ranon Katzoff and Greenfield, “Papyrus Yadin 18, ” IEJ 37 (1987), p. 231. The time difference is slight, and the interpenetration of Aramaic and Greek in Jewish culture is extensive and long lived. Many other circumstances could have dictated the language of the marriage contract, or it might have been a matter of indifference.

For the expression “Greek custom,” see Lewis, Katzoff and Greenfield, “Papyrus Yadin 18, ” pp. 239–241.

See Yadin, Greenfield and Yardeni, “Babatha’s Ketubba,” p. 94. The other, Galilean custom, allows the widow to remain and be maintained in her late husband’s house unless she remarries. The Palestinian Talmud, Ketubbot 4.15 (29a), approves of the Galilean practice as honorable and disdains the Judean as mercenary.

Flavius Josephus (The Jewish War, 3.3.5) lists the Roman province of Arabia among the toparchies just before the war with Rome. For other references, see Emil Schürer, Geza Vermes and Fergus Millar, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, 4 vols. (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1973–1987), vol. 2, pp. 190–194.

Lewis, Katzoff and Greenfield, “Papyrus Yadin 18, ” pp. 236–247. For a study of marriage contracts, see M.A. Friedman, Jewish Marriage in Palestine: A Cairo Geniza Study, 2 vols. (Tel Aviv and New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1979–1980). A briefer treatment can be found in Léonie J. Archer, Her Price Is Beyond Rubies: The Jewish Woman in Graeco-Roman Palestine, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament supp. ser. 60 (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1990). As P. Yadin 18 and 37, the two Greek marriage contracts, have nothing explicitly Jewish about them, some have disputed their Jewishness, including A. Wasserstein (“A Marriage Contract from the Province of Arabia Nova: Notes on Papyrus Yadin 18, ” JQR 80 [1989], pp. 105–130) and others. Katzoff has responded in “Papyrus Yadin 18 Again: A Rejoinder,” Jewish Quarterly Review 82 (1991), pp. 171–176, and elsewhere.

Gary Porton, Goyim: Gentiles and Israelites in Mishnah-Tosefta, Brown Judaic Studies 155 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988). Gary Porton, The Stranger Within Your Gates: Converts and Conversion in Rabbinic Literature, Chicago Studies in the History of Judaism (Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press, 1994), traces the tensions and paradoxes that the Mishnaic system caused in interactions with gentiles. The rabbis used a variety of strategies for marginalizing all outsiders in favor of an integral, divinely mandated, well-structured Israel. The rabbis’ view of Israel in relation to non-Jews was an ideal seldom experienced. It certainly does not describe, but may have been a response to, the kind of web of relationships mirrored in the Dead Sea documents.

See Yadin, “Expedition D,” IEJ 11 (1961), pp. 38–52, for preliminary publication of some passages and a description. Yadin (Bar-Kokhba, chaps. 10, 12) describes the contents of the letters; Fitzmyer (Manual, nos. 53–60) provides translations for the Aramaic letters. For a list of all the documents from the Bar Kosiba war, see Millar, The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.–A.D. 337 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1993), app. B., pp. 545–552.