BAR Jr.: Digging, Dug, Gone

042

Many people do not realize that archaeology is destructive. Unlike experiments in physics or chemistry, which can be repeated in the lab, once a site has been excavated it cannot be re-excavated. The archaeological remains are gone forever from their position in the earth. Therefore, the key word for the archaeologist is CONTROL. The archaeologist must have total control over all of the information revealed in the excavation, so that later, with the help of this recorded information, it will be possible to interpret the excavated material and learn as much as possible from it.

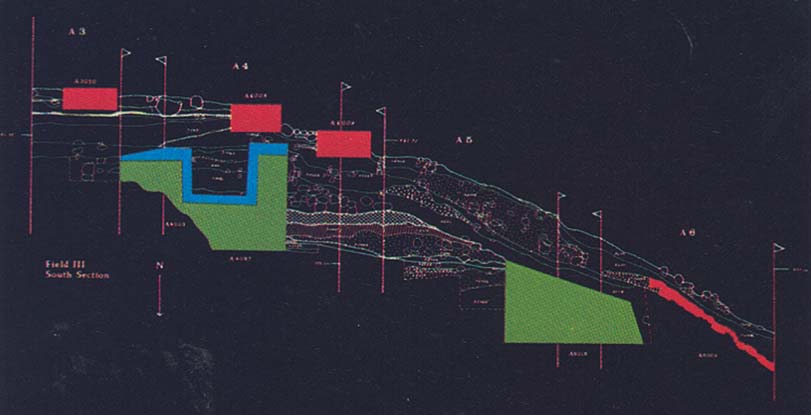

Excavation technique is a sequence of procedures, each one enabling the archaeologist to maintain this control. After selecting a site, the archaeologist first draws a plan of the entire area so that prospective excavation areas and dumps can be plotted on it. The next step is to choose the actual spots to be excavated. On a tell, usually the first area chosen for excavation is a steep slope where it is easy to penetrate and reach different layers. By making a vertical slice into the side of the mound, the archaeologist is able to get a sample of each layer within the slope. This procedure provides the stratigraphy, or the order of layers which make up the tell, and will expose the history of the site. Then the archaeologist chooses other areas for excavation on the basis of visible remains or topographical features suggesting the possible existence of important structures, such as gates, buildings, fortifications or walls.

After an area has been selected, it is marked with stakes and twine into a grid of 5 × 5 meter squares. Excavation in each square is directed by a supervisor who maintains tight control over his small area. Actually, an area of only 4 × 4 meters is excavated at first, leaving a meter of unexcavated soil standing between the squares. This one-meter wall is called a balk. The purpose of the balk, besides providing a catwalk between squares, is to retain a record of what has been excavated. Each layer or feature removed from the square can be related to a layer preserved in the balk. Often the feature, such as a floor or wall, continues from the excavated area into one or more balks. Some features may be entirely contained within a square but the level on which they were found will have its extension in the balk.

043

Each layer of deposit is referred to as a locus (plural, loci). Every three-dimensional feature, like a wall, a floor, a storage pit or an oven, is also a locus. Each locus receives a separate number by which it can be identified for both recording purposes and interpretation. As the square is excavated and the balk gets higher (or the floor gets lower), the archaeologist draws the side of the balk to scale and tries to interpret the material the balk has revealed as well as the relationships among loci. Lines or shapes in the balk will mark walls, floors, destruction layers or pits, and the archaeologist tries to find out how they relate to each other.

At the same time, the archaeologist plots on a plan (the view looking down) whatever is uncovered inside the square. Every feature or object discovered in the square has its elevation taken and is drawn on the plan. Together, the plan and the balk drawing (called a section drawing) provide a permanent three-dimensional record of the excavated square which has now been destroyed.

After the balk is drawn, it can be removed to expose what is buried within it or beneath it. Sometimes it is necessary to remove the balk to find connections between walls. The removal of a balk can also complete the picture of a structure, parts of which would otherwise be hidden in the balk.

Next, the archaeologist may remove part or all of a structure inside the square so that he or she can dig beneath to earlier layers. Such digging is 044possible only after everything above has been recorded on the plan and a complete set of photographs taken. New string lines are then stretched, the same balks re-established, and the process begins once again on a lower level.

The key to dating the different layers and finds is usually pottery. Although pottery is breakable, once it is broken the pieces hardly deteriorate at all. That is why ancient sites in the Near East are covered with so much broken pottery. Pieces of pottery are called sherds. Careful collection of excavation sherds, each with its own datable characteristics, provides the basis for dating other finds associated with this pottery. Pottery collection and interpretation are another phase of the excavation process that archaeologists keep under tight control.

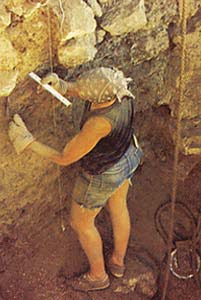

Excavators use various tools, according to the nature of the material being excavated. Large amounts of soil will be loosened by a large pick, then put into a basket with a hoe. The baskets are usually made of tire rubber and are called by their Arabic name, guffahs. Team members pour the contents of the guffahs into a wheelbarrow or a sifter. When work becomes more delicate, excavators will use trowels and a hand pick called a patish.

Brushes of different kinds and sizes are used constantly to clean the excavated area so that the archaeologist can see what is being uncovered. At a dig, as elsewhere, cleanliness is next to Godliness.

When work becomes even more delicate, for example, when a skeleton or jewelry is excavated, the archaeologist will use dental tools and very small, soft, narrow brushes. In addition to these tools, archaeologists use special instruments for level taking, surveying and drawing. Photographs record each step of the excavation.

A modern archaeological staff includes many specialists. Besides the archaeologists, the team includes a photographer, a registrar, a pottery restorer, a surveyor, whose responsibility is to draw maps and large-scale plans and to provide and check elevations, and draftspeople who draw certain features in the field or objects which have been processed by a conservator or restorer. Some excavation teams also include a paleozoologist, who studies ancient animals; a paleobotanist, who studies ancient plants; a physical anthropologist, who studies human skeletal remains; and a geologist, who studies the terrain and provides information concerning rocks and soils.

Any particular excavation will occur only once. Since it is impossible to re-excavate what has already been excavated, we must preserve every possible scrap of information about the site as we destroy it. With that information, we can start to fill in a picture of what life was like in antiquity—a picture to which future archaeologists may add when they return to our data with new understandings derived from their excavations and study.

Many people do not realize that archaeology is destructive. Unlike experiments in physics or chemistry, which can be repeated in the lab, once a site has been excavated it cannot be re-excavated. The archaeological remains are gone forever from their position in the earth. Therefore, the key word for the archaeologist is CONTROL. The archaeologist must have total control over all of the information revealed in the excavation, so that later, with the help of this recorded information, it will be possible to interpret the excavated material and learn as much as possible from it. Excavation technique is a […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username