“Walk about Zion … number her towers, consider well her ramparts, go through her citadels … ” (Psalms 48:12–13)

What distinguished an ancient village or town from a city? One thing, perhaps the most important, was fortifications. Fortifying a settlement reflected the importance attributed to it; fortifications meant that a settlement was worth defending. During the Persian and later periods (from the sixth century B.C. onward), not all cities were fortified. But before that time, in the Bronze and Iron Ages, fortification of cities was almost universal and constituted one of the chief differences between cities and villages or towns.

A settlement was fortified by surrounding it with structures that would keep an enemy out. These structures took different shapes and forms in different periods. They were invented to withstand certain weapons, and when these weapons were improved or new weapons appeared, the fortifications had to be modified to answer the problems created by the new military machinery.

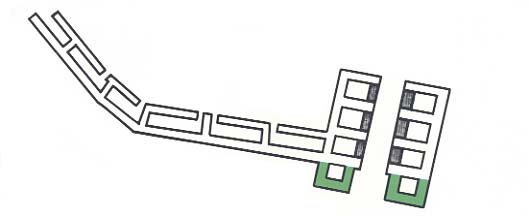

In Biblical times, the primary fortification was the city wall, which surrounded the city on all sides. During the period preceding the Israelite conquest and settlement of Canaan (before 1200 B.C.), cities were surrounded by thick, solid walls. In most cases, these walls had stone foundations with mudbrick superstructures. During the period of the United Monarchy, in the days of David and Solomon (about 1000–920 B.C.), the solid wall gave way to the casemate wall: two walls running parallel to each other. Short dividing walls at right angles to the parallel walls created elongated rooms between the long parallel walls. These rooms served as living quarters or storage areas and could be entered through openings in the inner walls. Some archaeologists suggest that in times of special danger, the casemate rooms could have been filled with rubble to strengthen them. In many cities, private houses attached to the wall incorporated these casemate rooms as living and storage space.

This casemate type of fortification was not limited to cities. It was also used in forts designed to defend trade routes, especially in the Negev. In the Southern Kingdom (Judah), the casemate wall continued to serve as the primary defense system until the fall of the kingdom to the Babylonians (587/6 B.C.).

After the Northern and Southern Kingdoms split apart following Solomon’s death (about 920 B.C.), the Northern Kingdom (called “Israel”) returned to the older method of defense by solid walls. Remains of these walls can still be seen in royal centers such as Dan, Hazor and Megiddo. Although solid, these walls did not follow a straight line. They are called offset-inset walls, a descriptive term indicating that a section of the wall protruded forward, outside the main line of the wall, then the next section was recessed, followed by another section jutting out. This building method gave the defenders a better view and more control of the wall line. The offsets served as turrets—an attacking enemy who reached the wall was vulnerable on three sides to the volleys of the defenders. Offset-inset walls helped protect against approaching battering rams, soldiers with ladders, and wall-undermining activities. The offset-inset system was sometimes combined with the casemate wall, as at Beersheba and other sites.

While the wall was the basic defense structure, it needed protection against scaling by ladders, undermining, or breaching by battering rams. This could be achieved by one or a combination of the following means: glacis, fosse, screen-walls, or towers.

The term glacis refers to a sloping rampart (the slope could be as much as 40 degrees) built of dirt layers, stones and other materials. Because of its slope, it held the enemy back and prevented attack by battering rams. Usually, the glacis was covered with a layer of hard material—stones or beaten earth. Its upper part covered the wall’s foundations and therefore provided protection for the wall against undermining. The glacis also slowed down onrushing enemy soldiers and presented a problem for those who tried to approach the city wall with ladders. In addition, the glacis would stabilize the sides of the mound on which a city was often built. Since the mound was created in large part by continual rebuilding activities, layer upon layer, the mound was sometimes in need of shoring-up, and the glacis served this function as well.

Recent excavations show that glacis-like structures were already in use in the Early Bronze Age (about 2500 B.C.), as for example at Tell Halif, but they became common in the Middle Bronze Age (1750 B.C. to 1550 B.C.).

A fosse is a dry moat or ditch which, when used in combination with a glacis, increased the height of the slope facing an enemy and lengthened the distance from the city wall at which the enemy would stand before initiating an attack. Fosses have been discovered at both Lachish and Beersheba.

Screen-walls were low walls constructed outside the main city wall on the glacis. Defenders could shelter themselves behind the screen-wall while keeping the enemy away from the main defense wall. Screen walls have been discovered at Gezer and other sites.

Towers—round, square, or semicircular—were usually situated at strategic positions, such as corners or vantage points. In most cases, towers were constructed as part of the wall, but projected outside in an offset manner, thus offering a better position for defending the walls. Towers, as part of city defense systems, appeared in the Early Bronze Age (about 2850 B.C. to 2650 B.C.), as the semicircular towers at Arad show.

The weakest point in any city’s defense system was the gate, because it constituted an opening in an otherwise closed system. Military planners in different periods devised many ways to protect this “Achilles heel” of the defense system. The most consistent elements in the defense of the city gate were towers flanking it on both sides. For a long time, archaeologists suggested, on the basis of architectural elements uncovered in excavations, that gateways had been covered structures that could serve as fortresses. At Tel Dan in Israel, recent excavations uncovered a complete gateway for the first time. An arch supported the covered part of this gateway. (See “The Remarkable Discoveries at Tel Dan,” BAR 07:05).

During different historical periods, the size and shape of gateways changed. In the Middle Bronze Age, gateways incorporated large stones (orthostats) that supported the cover or second story of the gateway (those at Gezer, Hazor and Shechem are examples). In the Solomonic period, gateways in royal centers, such as Gezer, Hazor and Megiddo, had three rooms on each side of the gateway, forming an elongated structure. During the period of the Divided Monarchy, most gateways had only two rooms flanking each side of the gateway. Some of the Solomonic, six-room structures were modified to four rooms.

Cities of special importance had more than one wall system and more than one gate. Many cities had fortified sections inside the city—citadels—where a last stand could be made. This section usually housed the city administration.

Unfortunately, history teaches us only one lesson about fortifications: that every fortification system had its vulnerability. In the end, few ancient cities escaped violent destruction.