Bedouin Find Papyri Three Centuries Older Than Dead Sea Scrolls

Subsequent excavations in bat dung by American archaeologist confirms original location of the papyrus scrolls; diggers find hundreds of additional small fragments in Jordan Valley caves.

016

Nineteen-sixty-one was the third winter of drought. In the Old City of Jerusalem there were long queues at the water spigots. Tribes of Ta‘âmireh bedouin were drifting north past Jerusalem. Whole families and clans were moving together, at times afoot, at times by donkey train with an occasional camel. They tramped up the tortuous central spine of Palestine, their flocks and herds consuming the sparse greenery. This year they had to move much farther north than usual, an added hardship in their spartan existence. It was nothing new. The Bible long ago celebrated long droughts as “seven years of famine.”

Many able-bodied Ta‘âmireh were absent from this northward trek. Some of the men had temporary or even permanent jobs and were beginning to adapt to village life. Most of the rest were searching for scrolls or other antiquities. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947 by two Ta‘âmireh shepherds produced more changes in the life of the tribe than it did in the text of the Old Testament. Even the pittance that finally reached their hands, out of the vast sums paid for the scrolls, was enough to stir the enterprising Ta‘âmireh. The trend of the times among the bedouin is toward sedentarization, but if one has to work, the freedom of a treasure hunt, with its promise of gold, is much more attractive than any other job. As a result, many of the men were off digging tombs in Tekoa, exploring caves in the Wâdi Murabba‘ât, and combing ruins in the wilderness of Judea. Every week or so they took a taxi up the Jordan Valley road to see their families on the northern trek, and then returned.

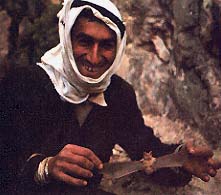

The Ta‘âmireh are tall and slender, and there are few cracks and crevices in the rock around Jericho and southward through which they have not squirmed. The trek northward early in 1942 provided occasion to investigate some new holes in the 019rock. While the exploration was anything but systematic, there was one area with high priority north of Jericho. This was the vicinity of the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh in the central hill country about halfway between Samaria and Jericho. That it was one of the most remote in central Palestine and accessible only by rugged footpaths was, of course, no problem for the Ta‘âmireh. Natural processes had hollowed out even larger and more labyrinthine caverns in this area than in the rest of the central ridge; in addition, the bedouin were attracted by the fact that a hoard of silver coins had been discovered in a cave here a couple of years before. This was the one area north of Jericho where treasures might be found. As the Ta‘âmireh pushed northward in pursuit of pasture, the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh was a magnet. Here able-bodied men could spend some time in pursuit of treasures.

For the bedouin the chronology of past events is linked to their great feasts. It was the beginning of Ramadan (early in February, 1962) when the Ta‘âmireh began encamping at Khirbet Fasâyil. Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim year, is the month of fasting. Not even a drop of water or a cigarette touches the lips of the pious from sunrise to sunset during that month. Khirbet Fasâyil is about fifteen miles up the Jordan Valley from Jericho and five miles east of the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh. The trek from Fasâyil to the wadi was uphill all the way, either up the canyon, or along the more circuitous path by which donkeys brought water from the Fasâyil spring to the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh.

Wâdi in Arab place names designates everything from a tiny gully to a rift of Grand Canyon proportions. The Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh best fits Webster’s definition of a ravine: “a small narrow steep-sided valley that is larger than a gully and smaller than a canyon and is usually worn down by running water.” Down the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh the winter rains tumble on their way to the Jordan River. It made a sharp gash into the eastern rim of Palestine’s central hill country, with sheer cliffs a hundred feet high and more. A prominent cascade divided the wadi into upper and lower portions.

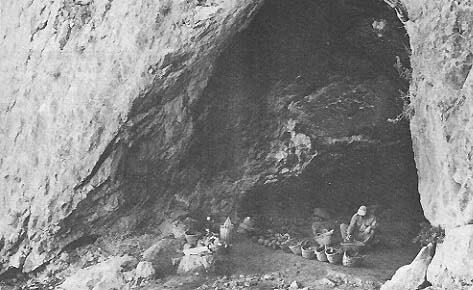

The cliffs on both sides of the wadi were honeycombed with caves. Many of them were small. Some of them were large and labyrinthine, with thousands of feet of passageways.

It was these labyrinthine caves that were the special object of Ta‘âmireh investigations as they moved northward during the winter of 1962. Two of the largest caves were located in the heart of the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh. Above the cascade on the north side of the wadi was the entrance to the “Caverns of the Sleepy One.” Just below the cascade on the south bank of the wadi, was the “Cave of the Father of the Dagger.”

Ta‘âmireh cave investigation is not an exact science, but it is not merely aimless rummaging either. Père Roland de Vaux, amazed at the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in Cave 11, asked the Ta‘âmireh discoverers how they had known to dig through such a depth of bat excrement to discover them. They replied that the cave was dry and, accordingly, a scroll discovery was possible. “Where did you learn this?” he asked. “You told us,” was their reply.

This meant that most of the obvious caves and holes in the rock which might look tempting to an uninitiated hunter were quickly dismissed by the Ta‘âmireh. They also knew that ancient caverns and passageways were frequently sealed by the buildup of guano (bat excrement) or other debris, by the rotting and collapse of limestone, or by the building up of lime deposits.

With this knowledge, the Ta‘âmireh employed primarily two methods of investigation in their search for scrolls. The first, and more obvious, was the exploration of passage upon passage in the labyrinthine caves, with test pits into the guano in promising chambers. Chambers eluding discovery by intensive exploration could be located by the tapping method. During the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh clearance on one occasion I noted several Ta‘âmireh precariously perched halfway up the steep rockface of the wadi. At first I thought they were trying to rescue a stranded animal. No, they had picks in their hands, and it looked as if they were carving graffiti. When I questioned them later, I discovered that they were pursuing their tapping exploration.

It was the hollow thud they heard while tapping on the rocky facade behind Qumrân that led to the discovery of Qumrân Cave 11, and it was the same hollow thud that led to the discovery of the Samaria papyri at the back of the main corridor of the “Cave of the Father of the Dagger”. About 60 feet back inside the cave, tapping suggested that there might be something beyond. Sledges and crowbars were brought for a massive assault on the limestone. After a couple of days of strained effort, a thin Ta‘âmireh was able to squirm through a tiny passage to the cavern on the other side. He drew back in dismay to report that there were signs that Ta‘âmireh had already been there. It was soon discovered that this spot was readily accessible from other passages of the cavern. The earlier Ta‘âmireh visitors had apparently been on a tapping mission and had not made a serious probe into the guano beneath their 020feet.

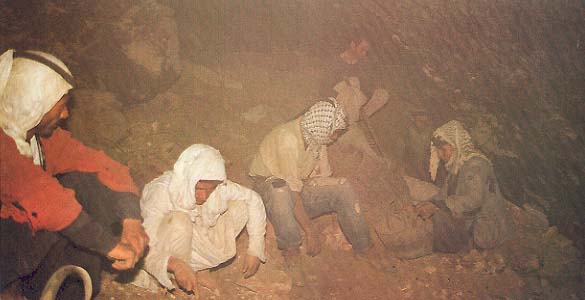

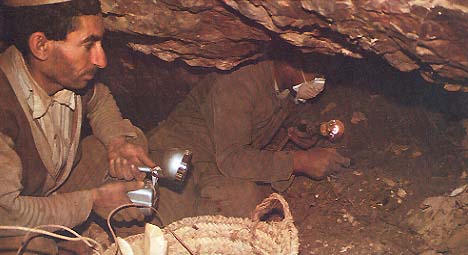

Burrowing into the stinking powder began in earnest. It was no pleasant task. The pungent smell of excrement still lingers in Dead Sea Scroll caves cleared over a decade ago. It is so loosely packed that a foot plunges two to three feet into it before stopping. Each footstep raises clouds of fine dust which soon obscures the faint torchlight in the cave. There is a high incidence of cancer among those who work for longer periods in guano, but this is of no concern to the Ta‘âmireh, when the lure of treasure is strong. The spot being dug was the inside end of two of the main cave passages. Beyond this were tiny crevices accessible only to the bats. The bat dung was unusually deep. The hole had to be continually expanded, and the excrement had to be pushed farther and farther away as it was dug to a depth of nearly six feet.

Six feet down something intriguing appeared. In the dim light it looked and felt like scrolls. The digger immediately rushed it out to the light of day. It proved to be nothing but fragments of matting. Continuing below the matting, the diggers turned up bone after bone—all human bones, as they immediately recognized. Then someone spied a gold ring and the hunt was on!

At this point a careful archaeologist would try to set up a foolproof surveillance while he planned a strategy for recording and recovering this piece of history; not so the Ta‘âmireh. Seven men had not much more than a square meter apiece as they dug feverishly through the night. Breaks in the work came only when disputes arose about lines between claims and how best to keep from throwing dung in each other’s faces. In their frenzy they tore ancient mats, trampled fragile ancient garments to bits with their feet, and smashed old pots to get at the gold they hoped was inside. Empty pots were smashed in disgust. After they had worked through the night, all they had to show was another gold ring and a few curious stamped lumps of clay (which they did not recognize as bullae—seal impressions—which would be of great value to scholars), some of which had human figures on them. Convinced that there was no real treasure they left the cave in disgust to look more closely at their finds. Everything looked the same in the early morning light outside the cave except that a few of the pieces of matting seemed to have been written on.

At this point our sources become as confused as were the finds in the cave. One reliable source disagrees with another, and both disagree radically with a third. All the accounts were given in confidence, and that confidence must be honored. What follows is what seems to me to be a plausible reconstruction. It is not unlike the problem of attempting to reconstruct a series of events from three or more literary sources, and the conclusions are no more reliable. It seems that two of the seven diggers went to Bethlehem that day with the fragments of what looked like scrolls. They showed them to a fellow-tribesman who had recently become active as a middleman between Ta‘âmireh diggers and antiquities merchants in Jerusalem. The middleman made a trip to Jerusalem late that afternoon and returned in the early morning. He told the two Ta‘âmireh that the two fragments they had were worth very little but he thought that there must be more which would be quite valuable.

Early the next morning the two headed south from Bethlehem to a Ta‘âmireh encampment near Tekoa where they consulted with a member of the tribe who was much experienced in scroll matters. He declined to become involved in the search but agreed to help out if scrolls were discovered. With that assurance, the two returned to the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh.

That evening around the campfire they discussed their strategy and traded stories about pots of gold and scrolls. The next morning they began a rather systematic search through the mixture of excrement, cloth, matting, bones, and potsherds. Soon after they had begun, women appeared with some rather primitive sieves. After they had sifted through the debris, they pushed it back into the passageway they had blasted through the rock, effectively blocking it again. As they sifted, they recovered a few beads, a small silver coin, and more clay sealings. After a couple of hours they found a small roll of papyrus. A quick view at the mouth of the cave confirmed their guess in the shadows. They rushed back, forgot about the sieves, and began ransacking the debris with their hands. Soon they had a dozen papyrus rolls, most of them only a few inches long, but one or two a foot long, still sealed with clay sealings. 021By mid-afternoon they felt that they had retrieved all the scroll material from the recess of the cave, and they began looking more carefully at other parts of the labyrinthine cave.

The next day two of their number went off with the scrolls to negotiate while the other five went to probe other promising areas of the cave and begin tapping for concealed chambers. The pair went off directly to their friend near Tekoa. The Tekoan took a sample roll and spent the next several days attempting to find a buyer in Jerusalem and even in Amman. He apparently received a fairly attractive offer for he was prepared to offer the seven something under five hundred dollars for the scrolls.

While the two were cooling their heels, word of the find began to spread and of course one of the first to hear was Khalil Iskander Shahin, commonly called Kando, the notorious middle man for the Dead Sea Scrolls. Before the Tekoan returned with his offer, an intermediary from Kando had persuaded the two Ta‘âmireh that Kando should be permitted to make a bid, and no one ever out-bids Kando for scrolls. The Tekoan was apparently somewhat taken back when his friends did not accept his generous offer and suggested that they would like to see how much Kando was willing to pay.

The Tekoan soon recovered his composure and agreed to serve as an intermediary with Kando. After consultations, he returned with word that Kando was willing to pay about seven hundred dollars for the lot; it seems safe to presume that Kando made a fairly handsome payment to the Tekoan. The next morning the transaction was quickly completed; Kando had the scrolls and the two Ta‘âmireh returned to the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh loaded with Jordanian dinars.

The five Ta‘âmireh who had remained back at the wadi probably had spent more of their time discussing the mission of their two friends than in further cave exploration. The five reported that their search had been fruitless, but all disappointment was forgotten with news of the successful negotiations. Their new riches occupied their attention for the next several days. A joint trip to Amman brought new watches and transistor radios to the Ta‘âmireh encampment. One of the group increased his holdings in a Bethlehem bus company. To another, it was the end of a long hard struggle to accumulate a bride price. After these delightful days, they were ready to search for more treasure.

Each followed his own intuition, and as the days passed, more and more tribesmen forsook their explorations to the south as they learned of the discovery in the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh. Spring found some seventy Ta‘âmireh tapping the rock and digging test pits in the caves around Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh. Much of the effort was undoubtedly duplicated, but even so there are few caves or rock-hollows in that area that have not been examined by the practiced eye and pick of a Ta‘âmireh. These investigations produced nothing except a few more bullae and a couple of silver coins. In disappointment, the Ta‘âmireh gradually drifted away from the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh.

Kando kept the scrolls for some two months before informing the Curator of the Palestine Archaeological Museum, Yusef Saad. Most of the pieces were undoubtedly kept under lock and key, but under conditions which did not prevent further deterioration. Meanwhile, Kando may have been exploring the possibility of disposing of the papyri through some Near East antiquity dealers. He is known to have been in Beirut during this time and it is not wholly speculative to suggest that he might have had a sample role with him. If he had made successful efforts in this direction, the discovery of the papyri might still have remained unknown. Who knows how many important groups of documents may yet come to light when the heirs of private collectors donate such finds to scholarly institutions. But fortunately, the Wâdi ed-Dâliyeh finds were brought to our attention in Jerusalem.

Late one afternoon in April, 1962, Père R. de Vaux of the École Biblique and Mr. Yusef Saad, Curator of the Palestine Archaeological Museum, paid a visit to the American School of Oriental Research [now the William F. Albright School of Archaeological Research], where I was serving as Director. They were excited about the contents of a tiny box they brought with them. In it was a small piece of worm-eaten papyrus with Aramaic written on both sides. I spent most of the night consulting our palaeography notes and charts and combing Aramaic dictionaries. The next morning I reported to Père de Vaux that the script belonged to about 375 B.C., that the fragment was part of an official document probably having to do with military administration, and that, although the fragment was too small to make continuous sense, the city of Samaria was clearly mentioned.a Thus the Samaria Papyri became known to the scholarly world.

This papyrus sample was part of the larger find consisting of many more fragments, some small 022rolls of papyrus, one still sealed with seven sealings, a collection of several dozen sealings bearing distinct Persian and Greek figures, and a few coins. Attempts on all sides to raise funds and negotiate a reasonable purchase price went on into November.

By November 19 negotiations were complete. The agreement enabled the Palestine Archaeological Museum to purchase the papyri with exclusive rights of publication, and I agreed to undertake the excavation of the discovery site.

Of course we were all anxious for a closer look at the purchases. That first night my wife Nancy and I watched with bated breath while Professor Frank M. Cross cut the seven seals of the prize piece. The fragile papyrus became pliable again when water was applied with a fine brush and the unrolling began.

The flattened roll was unwound six turns and still no writing appeared!

The next turn revealed that the original document had been wider, had had several more sealings, and on the missing portion signatures could be expected at the bottom where our piece was blank.

When the top line was reached, Professor Cross immediately read: The twenty-first of Adar, year two, the Accession year of the reign of Darius. The reference was to the second year of Arsames and the first of Darius III, 336/5 B.C.

On December 2 a Ta‘âmireh guide led Mr. Saad to the find site. Mr. Saad brought back some Iron II (eighth century B.C.) sherds and report of the long, difficult, and adventuresome walk to the cave from a point about a kilometer west of Khirbet Fasâyil. Having gone in the afternoon, he did not have time to explore the cave interior but hurried back to reach his car before nightfall.

Mr. Saad engaged a Ta‘âmireh guide to lead Père de Vaux, Nancy and me to the cave on December 11. When the Ta‘âmireh failed to appear, we left for Fasâyil with Mr. Saad as our guide. Driving west over the trackless waste west of Fasâyil we were unable to locate any Ta‘âmireh tribesmen. The few shepherd boys in the neighborhood ran off when we called them.

Finally, one man appeared to greet us, but he persisted in his ignorance about the cave until Mr. Saad was able to assure him we were not spies. He then led us on an hour-and-a-half walk to the cave area. It was honey-combed with caves, and in most of them heaps of sifted earth testified to the industry of the Ta‘âmireh diggers. The first cave we examined had a large mouth with a tiny passage about large enough for a slender Ta‘âmireh to squirm through at the back. Here we collected Middle Bronze I (20th century B.C.) and Early Roman sherds.

Then Mr. Saad led us to another group of caves where the manuscripts had been found. While we ate our lunch at the entrance we noticed pieces of human skulls and picked up Middle Bronze, Iron II, and Early Roman pottery.

After lunch, we prepared our lamps and crawled on all fours as far as our lamps could reach—some 210 feet, as we later measured. Walking, crawling, bobbing our heads to avoid bats and overhanging rocks, and covering our faces to avoid as much of the excrement dust as we could, we reached the far end of the cave, the place later confirmed as the manuscript find-spot. Noting the vast amount of sifted debris and picking up the first pottery that was clearly of the fourth century B.C., we took another passage and climbed a rather steep ascent. Here was a large cavernous room with at least six longer passages leading from it. Its ceiling was covered with layers of screeching bats. We followed one of its passages some 65 feet and found the same human bones and early Hellenistic pottery (4th century B.C.) that we saw at the manuscript find-spot and the passage leading to it. By then we were ready for some fresh air.

Our discussions of plans for sounding in the caves became less and less excited and more and more sober as we trudged back to the Land-Rover. Logistics would be the chief problem. How could we get camping gear to the site over paths impossible for donkeys? What arrangements could be made to supply the site with water from five miles away? Could we get workers when the drought was driving the Ta‘âmireh farther north? Where could a camp be placed when there was no flat land nearby? What kinds of masks and goggles could be obtained immediately for work in the dust, and what kind of lighting would be satisfactory for the caves? Would the bats present problems? Just what could be done with the small amount left in our archaeology budget?

Then, too, the visit indicated that prospects for results were only fair. The pottery, which might provide an important key to Late Persian and early Hellenistic pottery chronology, would probably be mixed. The large amounts of sterile debris sifted by the Ta‘âmireh would take much time to sift through, with prospects for perhaps nothing more than a few tiny pieces of papyri if we were lucky. Yet there were some places that seemed untouched by digging, and, in any case, the job had to be done.

023

Having decided to postpone work until after Christmas, we set January 7, 1963 as the first day of digging and decided to dig two—and if the circumstances demanded it three—weeks. We pitched some of our tents in the mouths of caves on both sides of the wadi and others nestled against the bases of the sheer cliffs of the wadi after terraces were constructed. (Those of us living within shadows of the cliffs tried to forget what might happen if rock above became dislodged or if it rained.)

Faithful Ali agreed—for a price—to supply us with water by a circuitous path his donkeys could negotiate, and he persuaded about ten of his friends to stay on and work—for a price. But no wage seemed unreasonable for climbing wadis five miles each way in order to work seven hours and a half in choking dust every day.

At the opening of the dig, we were delighted to find that fourteen Ta‘âmireh had appeared for work. Our plan was to start one crew working in the purported manuscript area and to divide the remaining workers into two crews which would begin a trench from the mouth of the cave to the manuscript area.

This trench would serve three purposes it would make it possible to reach the inside of the cave without the tiring crawl and squirm; it would reveal any openings or passages in the rock that might have been missed by the treasure-hunters on one side or the other of the passage; and, most important, it would provide a key to the history of the cave’s occupation.

We were amazed that by the end of the first day the two crews extended the trench inward almost 50 feet from the mouth of the cave and that the trench was already over 3 feet deep in spots. Meanwhile the manuscript area was producing 14 full baskets of pottery, human bones and skulls, cloth and sticks.

By the second day we were up to 26 workers. On our third day of digging, came the first papyrus fragments, which confirmed the find spot of the manuscripts. By now the number of skulls from that spot had increased to about 35, including those of men, women, and children of all ages, and we had found large quantities of cloth (some beautifully embroidered), wood, olive and date pits, and balsam nuts.

On the fourth day, the trench was nearing completion, much of it dug in undisturbed debris, and many more baskets of pots, bones and other materials (including papyri) continued to come from the manuscript area.

By Friday we were all ready for a rest. Finding our largest piece of papyrus with six Aramaic letters on it buoyed our spirits. The trench was completed, and it was now easy to get to the manuscript area. We paid the workers, hired two watchmen, and left for the weekend.

Our work had been handicapped by a lack of good lighting, so I spent Saturday in Jerusalem and Amman trying to locate a small generator that could be transported to the site and some batteries for floodlights. I could find neither, so we increased the number of our wick lanterns and had to continue working with them.

024

After an uneventful trip back and a good night’s sleep we were prepared for a rather uneventful week, but exciting finds continued. In fact, Monday was probably our most exciting day. In the manuscript area we found a clay sealing like those purchased with the papyri and a beautiful small scarab. On Friday, the sounding ended quietly with no necessity to consider a third week.

A word must be said about the unbelievable Ta‘âmireh who worked for us. Their strength was amazing. They worked at least twice as hard as any workmen I have ever seen on any previous dig. From the first day we could see that their working code disgraced any slacker, and the lack of a foreman to curb their fiercely independent spirits was a distinct advantage. They scrambled up rocky slopes in less than two minutes like goats, when it took the best of us fifteen minutes of cautious climbing to do the same. There were no misgivings on the part of our best men when faced with the task of carrying out heavy pots a meter high and nearly as wide to the car five kilometers away. One of these was the famous Muhammed edh-Dhib Hassan, who began the search for Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts by throwing a stone into Qumran Cave 1 in 1947.

Our second clearance operation took place in February 1964. We undertook limited clearance operations along the trench to the Manuscript Area to probe for cavities in the cave wall, but our main task was sifting through the remaining debris in the Manuscript Area. This tedious operation produced few surprises: more of the sherds, broken bones, tatters of cloth, sticks, pits, and seeds we had become so familiar with last season—and the pieces seemed even smaller! We were somewhat encouraged by the few beads which turned up almost daily, a fibula, two bullae, and almost daily papyrus bits with hints of a letter or two. As we were nearing the end, we made our prize find: a larger papyrus fragment with six lines of text containing as many as eight letters in a line, apparently the only larger fragment missed by the Ta‘âmireh.

With our objectives nearly accomplished, it appeared that we would be able to get away a day or two earlier than planned. Several of our Ta‘âmireh friends did not like the prospect of losing a good job so soon, and Muhammed Musa undertook the job of trying to convince me that there were still many potential treasure spots which had not yet been explored. Several of these I already knew about, but they did not seem especially attractive. They were too damp for manuscripts; there were very few sherds (but, of course, a coin hoard might be found).

Then the two of us squirmed on our bellies into a small room through a passage too small for the other member of our group to come along. This room had a good scattering of sherds from the second century A.D. We repeated the squirming process, entering a second room with similar pottery. A passage led to another room with the same sherds and no exit, but another passage led to a larger room, then to a fifth and sixth room each increasing in size. The sixth was a fairly large cavern in which we could walk around to explore its nooks and crannies. We did not linger long here, for Muhammed found a shaft which led to an underground wadi which extended as far as our spotlights penetrated in either direction. The bats were hanging in layers on the walls, and Muhammed and I alternated shrieks when they landed on us. After what seemed like a kilometer but was only a couple of city blocks the passage narrowed, and we passed through a tiny opening into a cavern in which one might have placed a football stadium. The air was warm and humid enough to keep the rocks slippery. We began to explore the passages off the cavern, but were afraid to go too far in any of them.

When we were ready to go back, Muhammed had lost his sense of direction and rushed about frantically searching for the tiny exit. Finally, when he slipped and hurt his leg, he became more composed, and I was able to make a systematic search, which led to the exit in a few minutes.

We had not made a new discovery. There were scattered evidences of recent diggings. A few sherds and bones here and there told us that this underground labyrinth was known in the second century A.D.

By now we were only concerned with getting out It was quite a relief to get back to the familiar part of the cave after over two hours of exploring.

Far from luring me to more work, this adventure convinced me that, aside from clearing the first few small rooms, we should turn the whole thing over to the Ta‘âmireh or anyone else whose spirit of adventure would be less easily dampened than mine. So we left the caves open when we left. We were not sure that all important finds had been made, but we were convinced that it would be much safer and more sensible to pay off a lucky adventurer than to continue the search.

(For further details see Discoveries in the Wadi Ed-Dâliyeh, edited by Paul W. Lapp and Nancy L. Lapp (Cambridge, 1974), Chapters 1 and 2, from which this article has been excerpted.)

Nineteen-sixty-one was the third winter of drought. In the Old City of Jerusalem there were long queues at the water spigots. Tribes of Ta‘âmireh bedouin were drifting north past Jerusalem. Whole families and clans were moving together, at times afoot, at times by donkey train with an occasional camel. They tramped up the tortuous central spine of Palestine, their flocks and herds consuming the sparse greenery. This year they had to move much farther north than usual, an added hardship in their spartan existence. It was nothing new. The Bible long ago celebrated long droughts as “seven years of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username