In putting together this issue’s article on the Antiquities Problem (“The Great MFA Exposé”), our thoughts turned to unprovenanced objects that can now be studied by scholars because they were bought on the market. If these important remnants of the past had not been purchased—perhaps, in some cases, illegally—they would have disappeared from view for decades or perhaps forever. A good example is the Dead Sea Scrolls (see photo of the Isaiah Scroll), almost all of which were bought from antiquities dealers. Among the most exciting archaeological finds of the 20th century, the Dead Sea Scrolls contain biblical manuscripts (among other documents) a thousand years older than our earliest copy of the Hebrew Bible, providing fascinating new insights into how the biblical text developed. Who could reasonably prefer that the scrolls, because they were not found in a legal, controlled excavation, remain untouched by responsible scholars? In the following section, we have assembled a group of similar finds, which have checkered histories and yet illuminate the past: a clay prism mentioning the mysterious

Cuneiform Prism

This umprovenanced prism may tell us who the Hòabiru were.

8½ inches high

clay

early 15th century B.C.

King

The origins of this baked clay prism are equally obscure: No one knows where, when and how the prism was discovered. It now belongs to a collector, who has allowed the distinguished Italian scholar Mirjo Salvini to publish it.

The cuneiform text consists of 438 masculine names written in eight columns, two on each of the four sides. At the bottom, a colophon notes that these are workers who served the king.

The king’s name and many of the workers’ names are Hurrian. Several of the other names are Semitic, and some are of unknown origin. All 438 are identified as

Ivory Pomegranate

Where this ivory pomegranate was found and who sold it to the Israel Museum for $550,000 remains a mystery.

1½ inches tall

ivory

late 8th century B.C.

Looming large in the world of biblical archaeology is this diminutive ivory figurine. Carved in the shape of a pomegranate, a common fertility symbol in the ancient Near East, the ivory probably served as the decorative head of a ceremonial scepter. A wooden rod would have been inserted in a small hole bored into its bottom.

The fragmentary inscription has been reconstructed as “Holy to the priests, belonging to the H[ouse of Yahwe]h”—indicating that the scepter was once carried by priests in the Jerusalem Temple, dedicated to the Israelite god Yahweh. (A few scholars, however, argue that it is equally possible to reconstruct the name as “Asherah,” the Canaanite fertility goddess.) The Old Hebrew script dates to around the time of King Hezekiah (727–698 B.C.), who attempted to centralize Israelite worship in the Jerusalem Temple. No other artifact from the Temple built by Solomon has survived.

In July 1979, the French paleographer André Lemaire wandered into the shop of a Jerusalem antiquities dealer, who invited Lemaire to return another day to see a small inscribed ivory. Over a cup of tea, the dealer showed Lemaire this tiny pomegranate, which had either been found accidentally or illegally excavated. Lemaire photographed the ivory and published it in the French journal Revue biblique.

Biblical Archaeology Review published an English version of Lemaire’s article in 1984, and the pomegranate instantly attracted worldwide attention. Three years later, a well-known tour guide visited the Israel Museum with a copy of the BAR article under his arm. Claiming that he had been approached by intermediaries, the guide asked if the museum would like to purchase the pomegranate for $600,000. Meanwhile, the pomegranate had been smuggled out of Israel and was on exhibit in Paris’s Grand Palais.

The Israel Museum immediately began trying to raise the money. In 1988, the museum received word through an agent that an anonymous donor in Basel planned to give the museum one million Swiss francs, about $675,000. The museum asked the agent whether the money could be used to purchase the pomegranate. The donor agreed.

According to our sources, the pomegranate was originally purchased from a Jerusalem antiquities dealer for $3,000. The Israel Museum paid $550,000. Now on display in the Israel Museum, the ivory pomegranate was exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in November 1993 in an exhibit sponsored by the Biblical Archaeology Society.

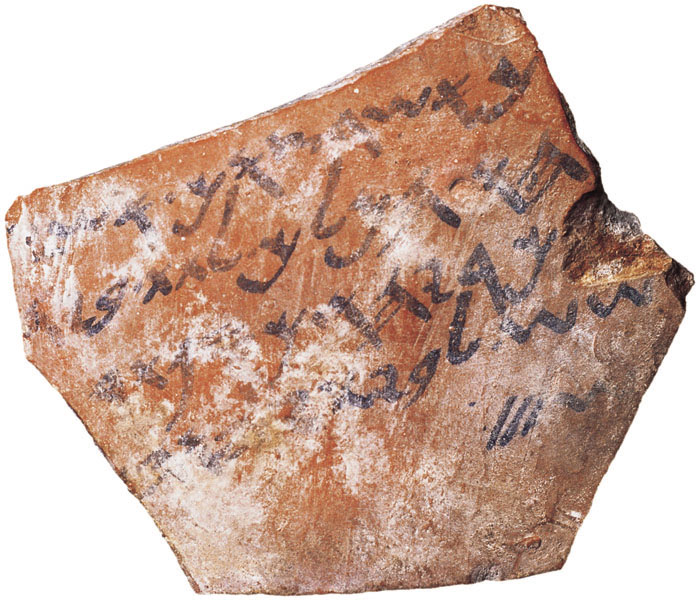

Three Shekel Ostracon

The oldest reference to King Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem appears on this ancient receipt.

3½ inches tall

terracotta

late 8th century B.C.

This mundane-looking pottery sherd is an ancient receipt for a three-shekel donation to the Jerusalem Temple. The Old Hebrew inscription reads, “As Ashyahu the king commanded you to give into the hand of [Ze]chariah silver of Tarshish for the House of Yahweh: shekels /// (three).”

Although the Bible never mentions King Ashyahu, this name may be a transposed form of Joash or Jehoash. If so, the inscription probably dates to the early years of King Jehoash, who ruled the southern Israelite kingdom of Judah from 835 to 801 B.C. Zechariah is the name of a prominent priest from that time (2 Chronicles 24:20).

The young king Jehoash proclaimed that all contributions to the Temple be turned over to the priests for repairs to the building. But Jehoash later observed that the silver received by the priests was not being used to repair the Temple, so he arranged for the funds to be deposited directly with the workmen (see 2 Kings 12).

Several lab tests conducted on this ostracon, which was purchased on the antiquities market and belongs to the collector Shlomo Moussaieff, confirmed the antiquity of both the pottery and the ink.

Hezekiah Bulla

“There was no one like him among all the kings of Judah” (2 Kings 18:5).

½ inch in diameter

clay

late 8th century B.C.

Deciphering the name impressed on this bulla, above, proved to be impossible even for Nahman Avigad, the late dean of Israeli epigraphers: Simply too few of the letters have survived. But when a more complete impression, below, of the same seal surfaced in the London collection of Shlomo Moussaieff, the mystery was solved: The better-preserved inscription clearly reads: “Belonging to Hezekiah (son) of Ahaz, king of Judah.” Hezekiah ruled the southern Israelite kingdom of Judah from 727 B.C. to 698 B.C.

This is only the second Judahite royal seal impression to come to light; coincidentally, the first belonged to Hezekiah’s father and predecessor, the Ahaz mentioned on the impression. Hezekiah’s seal bears the image of a winged scarab beetle pushing a circular ball of dung, which represents the movement of the rising sun and symbolizes the deity bringing salvation. Winged scarabs and sun disks have been found on hundreds of inscriptions dating to the reign of Hezekiah—who is highly praised by the biblical authors for his kingship and religious reforms.

Baruch Bulla

The faint whorls of a fingerprint on the upper edge of the bulla may have been left by Jeremiah’s scribe.

½ inch in diameter

clay

late 7th century B.C.

Get a scroll,” the Lord commanded Jeremiah just before the Babylonians attacked Jerusalem, “and write on it all the words that I have spoken to you.” So “Jeremiah called Baruch son of Neriah; and Baruch wrote down in the scroll, at Jeremiah’s dictation, all the words which the Lord had spoken to him.” The prophet then instructed Baruch to read the scroll aloud in the Temple. And “Baruch son of Neriah did just as the prophet Jeremiah had instructed” (Jeremiah 36:2–8).

This clay seal impression, called a bulla, belonged to that very Baruch, Jeremiah’s scribe. The inscription reads “Belonging to Berekhyahu, son of Neriyahu, the scribe.” The Hebrew script dates the bulla to the late seventh century B.C., the time of Jeremiah. The faint whorls of a fingerprint on the upper left edge may have been left by Baruch himself.

Papyrus scrolls were commonly tied with string and then sealed with a lump of clay. A scribe would press a seal into the clay, making the document official. Two clay bullae impressed with Baruch’s personal seal have come to light. The gray bulla shown here is owned by the London collector Shlomo Moussaieff; a second bulla, without a fingerprint, is in the Israel Museum.

The museum’s bulla was part of a large collection of bullae published in 1986 by the late Nahman Avigad, then the leading Israeli authority on ancient Hebrew seals and sealings. For several years, similar bullae had been appearing in the shops of antiquities dealers in Bethlehem and Jerusalem. Although Avigad never discovered where the bullae were coming from, he determined that they belonged to a single hoard. Apparently Arab villagers had somehow got hold of the archive and sold the pieces to dealers.

Jerusalem collector Yoav Sasson acquired 200 of the bullae, and Reuben Hecht of Haifa obtained about 50, which he donated to the Israel Museum. All 250 were made available to Avigad for publication. But some pieces from the hoard, including the Moussaieff bulla, never came to Avigad’s attention.

Baalis Seal

A biblical murderer was the original owner of the first Ammonite royal seal to come to light.

½ inch in diameter

brown agate

early 6th century B.C.

A muscular sphinx—symbol of royalty—dominates the central register of the first seal of an Ammonite king ever to come to light. The partially damaged Ammonite inscription reads:

“Belonging to Ba’alis, King of the Sons of Ammon.” The seal, bought on the antiquities market, is now owned by an anonymous collector.

The Ammonites lived east of the Jordan River. The remains of their capital lie beneath Amman, Jordan, a city that preserves the name of the ancient people. According to the Book of Jeremiah 40–41, after the Babylonians destroyed Judah in the early sixth century B.C., the Ammonite king Ba’alis dispatched an assassin to murder Gedaliah, the Babylonian-appointed governor of Judah.

Gold Libation Bowl

As vases for the gods, phiales were made of precious materials—glass, onyx, silver and, rarely, gold.

9 inches in diameter

22 karat gold

4th century B.C.

Nuts and bees—representing fertility—decorate this Greek libation bowl, called a phiale, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The photo shows the vessel’s bottom; the hammered-gold bowl bears three concentric circles of 33 acorns and one of 33 beechnuts. A central boss representing the world’s navel (in Greek, omphalos) lends the bowl its technical name: phiale mesomphalos. Between the acorns in the outer circle are bees, recalling the Greek poet Hesiod’s description of the good life: “The earth brings forth livelihood aplenty, and the oak in the mountains bears acorns on top and in the middle bees.”

Libations involved offering wine or precious oil to a deity. From Greek vase paintings, we know that wine was poured from a jug into a bowl such as this phiale, which then was tipped to spill the liquid onto the ground.

A partial Greek inscription (“Pausi ”) scratched into the gold at the bottom of the bowl may be the beginning of a personal name. Another inscription, in Carthaginian script, can be dated to the fourth century B.C. by the form of its letters; this inscription appears to record the weight of the bowl as 180 drachmas—a Greek measure of weight, suggesting that the bowl was produced in a Greek community. Nonetheless, as the Metropolitan Museum has reported, “Nothing precise is known of its provenance.” The bowl may have been found in the Mediterranean: Before cleaning, it was heavily encrusted with the remains of marine invertebrates.

Ancient temple inventories record that phiales were made of various precious materials—glass, terracotta, onyx, bronze, tin, silver and, rarely, gold. One of the few other gold phiales known today—bought on the market in the early 1990s by Wall Street investor and art collector Michael Steinhardt—bears so striking a resemblance to the Metropolitan bowl that the two vessels are thought by some to have been made in the same workshop. The Steinhardt phiale has concentric circles of 36 (rather than 33) acorns, bees and beechnuts, and it is made of 24 karat (rather than 22 karat) gold. An inscription on the Steinhardt bowl records that it was dedicated to the gods by Achyris, who is identified as a “demarch,” a high political office in Greek colonies on Sicily.

Steinhardt purchased the bowl for $1.2 million from an American dealer. The U.S. Customs Service seized the bowl from Steinhardt in 1995, after the Italian government claimed that the vessel had been stolen. A federal judge ruled in 1997 that the bowl, which had passed through several hands before reaching Steinhardt, had been imported under false pretenses and in violation of Italy’s antiquity protection laws. Although the court noted that Steinhardt was “entitled to a full refund” of the purchase price, he has appealed the decision. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit is expected to rule within the next few months. While the case is pending, the bowl is being held by the court.

Isaiah Scroll

The price tag on the most sensational archaeological discovery of the century: $14.

24½ feet long

sheepskin

late 2nd century B.C.

If it is genuine,” John C. Trever wrote to his wife when he first saw this scroll of the Book of Isaiah (below), “it may prove to be a sensational discovery.”

It was authentic, and the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls—from several caves near Qumran, on the northwest coast of the Dead Sea—dazzled the world.

This well-preserved scroll, containing all 66 chapters of Isaiah, was among the first scrolls discovered. In 1947, a Bedouin shepherd saw a small cave opening in the rock. Inside were narrow pottery jars containing scrolls. The shepherd snatched a few and left; among the spoils was this scroll, known as 1QIsaa, shown open to Isaiah 58:6–65:18.

The Bedouin sold some of their scrolls—for about $14, according to at least one report—to a Bethlehem dealer named Kando. Eventually the Isaiah scroll and three other scrolls were resold to the Metropolitan Samuel, the Syrian Orthodox Archbishop of Jerusalem. These scrolls were later bought by the State of Israel for a $250,000.

The Dead Sea caves held over 800 manuscripts—almost all were mere fragments, and most were bought on the antiquities market from Bedouin. The scrolls date from the second century B.C. to the first century A.D. They include biblical manuscripts, Bible-like hymns and other sacred texts, and sectarian documents. The cache contained 18 manuscripts of Isaiah, in varying states of preservation. The photo above shows the scroll on display in the Shrine of the Book, in Jerusalem.

Ennion Cup

Ennion’s glassware outshone the works of the masters of Alexandria.

4½ inches in diameter

glass

1st century A.D.

Ennion made it.” The signature of the first-century glassmaker from the Phoenician city of Sidon is impressed, in Greek, on this glass wine cup belonging to London collector Shlomo Moussaieff. Around the turn of the millennium, Phoenician artisans revolutionized glassmaking, surpassing their rivals—the master glassmakers of Alexandria. While the Alexandrians kept to old methods of cutting and molding glass, the Phoenicians began to refine the art of glassblowing; their earliest pieces were made by blowing glass into molds impressed with decorations. Vessels made in the early decades of the first century A.D. and stamped with the names of glassmakers from Sidon, in modern Lebanon, have turned up throughout the Roman world.

Of these glassmakers, Ennion was the most prominent. The cup shown above, which is the only piece from its mold known to have survived, has Ennion’s name and four pairs of animals: a bull taking on a lion, a hound confronting a hare, and two pairs of fighting birds.

An amphora-shaped vessel with Ennion’s name was found in the excavations of the Old City in Jerusalem. A similar piece, now on display in New York’s Metropolitan Museum, may have been used at one of the three Jewish pilgrimage festivals celebrated at the Jerusalem Temple; each side of the vessel depicts a ritual object associated with the Temple, such as the menorah. Many of the Phoenician glass vessels found in the outposts of the Roman world may have been brought from Jerusalem by Jewish Diaspora residents who made pilgrimages to the Holy Land.