“Brother of Jesus” Inscription Is Authentic!

026

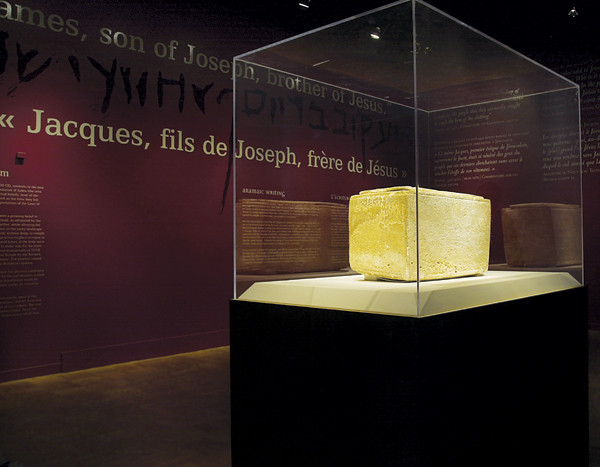

In all the hubbub and flurry of the verdict last March in the “forgery case of the century,” one question—the central question—seems to have gotten lost: Is the ossuary inscription “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” genuine or not? And if it is, does it refer to Jesus of Nazareth? After all, “Jesus” was a common name at the time.

These are enormously important questions to the world of Christianity, as well as to anyone else interested in the material world as it existed at the time Jesus walked this earth.

As to the authenticity of the inscription, while we should not avoid reasons for doubting the authenticity, neither should we dismiss it simply because it is “too good to be true.”

Is the inscription authentic? The court held only that the prosecution failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the inscription was a forgery. But it surely did not find that the inscription was authentic. I have no doubt, however, that it is.

027 028

Why the Inscription Is Authentic

Two world-class experts in paleography (the art and science of authenticating and dating inscriptions based on the shape and stance of the letters) have expressed their view that it is. They are André Lemaire of the Sorbonne and Ada Yardeni of the Hebrew University.

I would like to see any paleographer of any repute get up and state that Lemaire and Yardeni are wrong in their paleographical judgment in this case and then tell us why they believe Lemaire and Yardeni have erred.

I don’t think such a paleographer can be found!

There are scholars who have expressed their doubts about the inscription’s authenticity. The doubter-in-chief is my friend Eric Meyers, professor at Duke University and former president of ASOR (the American Schools of Oriental Research). Read his reaction to the judge’s verdict.1 He is very doubtful, but he gives absolutely no reason for his doubts. In fact, he is not even a paleographer. His position is grounded in the fact that he is against unprovenanced artifacts. It is true that we don’t know where the ossuary was found. It was probably looted from some burial cave. But this doesn’t mean it is forged. If it is forged, tell me why you think so. But don’t tell me it is forged simply because it was looted.

Meyers also objects to the way the ossuary was first presented to the public—at a joint meeting of ASOR and SBL (the Society of Biblical Literature) at their annual convention; the ossuary was exhibited at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto. In Meyers’s view, the inscription should not have been presented in this way. It should have been studied and then published in a scholarly journal, perhaps years after it came to light.

Meyers is quite explicit about why he is doubtful of the inscription’s authenticity. He brags that he was an early objector: “I was among the very first to question the wisdom of such an exhibition [at the ROM] after the artifact had a questionable provenance and had come to the public’s attention with such hoopla.”

What in the world does this have to do with whether the inscription on the artifact is authentic or not?

Professor Meyers goes on: “I also drew attention to aspects of the inscription that seemed questionable at best.” Please tell us what aspects you are referring to and why you find them questionable.

Although Meyers raises no substantive question as to the authenticity of the inscription in his post-verdict 029 reaction, he is more right than he realizes. All the doubts about the authenticity of the inscription arise because of the “hoopla,” to use Professor Meyers’s word, with which it was brought to the public’s attention. To make matters worse, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) learned of the inscription from this “hoopla,” rather than as an insider. The IAA was furious.

The Real Reason for the IAA’s “Doubt”

I first learned of the ossuary and its inscription from Professor Lemaire when we had dinner together at a Jerusalem fish restaurant catty-corner from the King David Hotel. Realizing the potential significance of this ossuary, I arranged (and BAR paid for) a scientific examination of the inscription by the official Geological Survey of Israel (GSI). GSI geologists found no reason to question the authenticity of the inscription. I also arranged for the inscription to be examined by Father Joseph Fitzmyer, the world’s leading expert in Aramaic (the language of the inscription), who gave his imprimatur to the Aramaic. And of course Professor Lemaire had found the inscription paleographically sound. I thought this was enough to publish Professor Lemaire’s article on the ossuary and its inscription, which he wrote at my request.

We announced the find at a press conference on October 21, 2002. The next day the ossuary was on the front page of every newspaper in the world, including The Washington Post and The New York Times. When journalists contacted the IAA for comment, they were embarrassed and furious: They knew nothing about the object.

Within a month of this announcement, thousands of Biblical archaeologists and Bible scholars would be having their annual meetings in Toronto. So I arranged for an exhibit of the ossuary at the ROM. We had a special showing for the scholars and—horrors!—the general public was also allowed to see it. A hundred thousand of them waited in line to do so.

In order to export the ossuary from Israel to Canada, however, we needed the IAA’s permission. I asked Oded Golan, the owner of the ossuary, to ask the IAA for its permission. He did so, informing the IAA of the contents of the inscription and noting that the object had been insured for $1 million. Permission was granted.

If the IAA was furious at the announcement of the ossuary at our press conference, it went bonkers at the fact that it was on display in Canada—and with their permission. (When we asked their permission to extend the exhibit for a few weeks because of the crowds who wanted to see the ossuary, the IAA, awakened to the importance of the inscription, refused. Permission denied!)

This, then, as Professor Meyers explains, is the “hoopla” that is the real reason for the “doubt” about the authenticity of the inscription. And I can prove it:

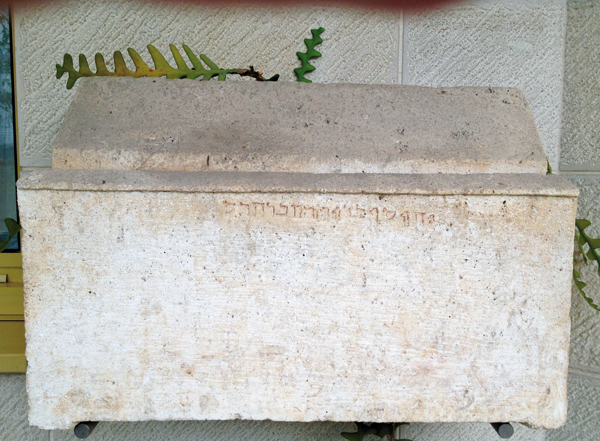

Long after the IAA brought the criminal case against Oded Golan, it seized 030 an unprovenanced ossuary that also had an inscription. The inscription, like the James Ossuary, is in Aramaic and comes from the same period as the James Ossuary. The inscription reads “Miriam, daughter of Yeshua [the same name translated “Jesus” on the James Ossuary], son of Caiaphas [perhaps a member of the family of the high priest by this name who presided at the trial of Jesus], priest of Ma‘aziah from Beth ’Imri.”a

The big difference between this ossuary and the James Ossuary is that the IAA had control of the Miriam Ossuary, unlike the James Ossuary. So the IAA arranged for the Miriam Ossuary to be studied by Tel Aviv University clay expert Yuval Goren, who was to be the government’s chief witness in the forgery trial about the James Ossuary and other artifacts. After a single test involving only himself, Goren reported that he had established the authenticity of the inscription on the Miriam Ossuary. He and Israeli archaeologist Boaz Zissu wrote an article on the Miriam Ossuary in the Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ). This was the way—the proper way—the Miriam Ossuary inscription was made known to the public. The IAA didn’t even consider it necessary to consult a paleographer to make sure the inscription was authentic. Yuval Goren’s scientific test was enough. (No one asked him why he didn’t apply the same test to the James Ossuary.)

No one—yes, no one, not Professor Meyers nor any other scholar—has raised any question about the authenticity of the Miriam inscription. The difference in the way that the IAA (and the scholarly world) has treated this inscription in comparison to the treatment of the James Ossuary inscription is startling. The difference lies not in the inscriptions themselves, but in how they came to (or did not come to) public attention. Professor Meyers tellingly reveals—perhaps unintentionally—the real reason for doubting the authenticity of the James inscription.

Professor Meyers does not pretend to be a paleographer. And he has not specified any aspect of the inscription that is questionable on paleographical grounds. He just has a generalized doubt about seemingly important inscriptions that are unprovenanced and are announced to the public with “hoopla.”

Unlike Professor Meyers, Professor Christopher Rollston is a paleographer of some note. He contributed two pieces to the ASOR blog after the judge handed down his verdict in the forgery trial. In one he talks about past forgeries. In the other, he talks about the motivations of forgers. But he says not a word about the inscription on the James Ossuary. He doesn’t even cast “doubt” on the authenticity of the James Ossuary inscription. 031 He doesn’t like unprovenanced inscriptions—in fact, he hates them—and that’s a reason to be suspicious of all of them. But that’s as specific as he gets.

Why the IAA Lost the Case, According to the IAA

One other point: The IAA would have us believe that it lost the case because it could not get a crucial witness, an Egyptian craftsman or jeweler named Marco, to testify on behalf of the government. His absence from the trial was important enough for the IAA to mention it in its post-verdict press release; that’s why the IAA lost the case: “During the investigation, the involvement of an Egyptian citizen by the name of Marco became apparent, who acted together with Oded Golan. Marco, a craftsman and jeweler by training, created several of the items for Golan. Nevertheless, all attempts by the state [of Israel] to bring the Egyptian to Israel in order to testify in court in Jerusalem were unsuccessful.” If they could only have gotten Marco to testify, they would have won the case.

On the contrary, the report of the team of Israeli police who went to Egypt to interview Marco says that Marco denied that he did anything wrong. And Marco’s denial is consistent with what Marco told an Israeli newspaper. And that is consistent with what Marco told me.

I talked with Marco in his small third-floor walk-up workshop in Cairo’s dense Khan Khalili bazaar. He was very clear that he never helped Oded Golan to forge anything.2 It’s a good thing the prosecution did not call Marco as a witness: He would have hurt their case still more.

In any event, to think that Marco, who makes his living crafting tourist trinkets, could forge “brother of Jesus” so skillfully at the end of the inscription on the side of the James ossuary that it would fool André Lemaire and Ada Yardeni is laughable.

Goren Crumbles; Zias Fibs

There is no question that the IAA wanted to get Oded Golan. And they found two human vehicles for doing so. The first was the aforementioned clay specialist from Tel Aviv University named Yuval Goren. The second is a former IAA employee named Joe Zias who had been let go during a budget squeeze in 1997.

Early in the government’s investigation of the ossuary inscription, Professor Goren discovered a fake patina on the inscription that he said the forger put on it in order to cover up evidence of forgery beneath. Goren cleverly called this fake patina the “James Bond” because, like real patina, it was supposedly bonded to the surface of the ossuary.

Problems quickly developed, but they were just as quickly overlooked. Professor Goren said the James Bond was made of crushed limestone and water, but this mixture wouldn’t bond without the addition of acid, which would easily be detected—and there was none. Besides, the James Bond wasn’t bonded; it could be removed with a toothpick.

Moreover, in his earliest report Professor Goren admitted that the James Bond could have been produced by cleaning the inscription, something antiquities dealers customarily do to inscriptions to make them “show” better.

Finally, one member of the government’s team, a conservationist named Orna Cohen, found original ancient patina in the word “Jesus,” despite Professor Goren’s contention that it was a forgery covered with James Bond.

In its eagerness to prosecute, the IAA ignored all these signs of trouble ahead. The criminal indictment alleged that “Defendant No. 1 [Oded Golan] … disguised the fact that part of the inscription was added recently. Defendant No.1 did so by applying various substances on the ossuary, in order that the inscription, when tested, would appear to be an inscription entirely written during the Second Temple period, by virtue of its being covered with patina which is supposedly from the Second Temple period.”

Under cross-examination at the trial, Professor Goren crumbled. When shown pictures prepared by the defendant’s expert showing original patina under the James Bond, Professor Goren became flummoxed and asked for a recess so that he could examine the ossuary itself as opposed to the expert’s pictures. The next day, Professor Goren returned to the stand and admitted the original patina was there—in the word “Jesus” yet! And if original patina was there, the letters were at least hundreds of years old.

Does this mean Professor Goren now accepts the authenticity of the inscription? Not quite. He has suggested that the forger may have used—as strokes in the forged letters—ancient scratches in which natural patina developed over the centuries. In a post-trial blog posted on the Web site Bible and Interpretation, Professor Paul Flesher of the University of Wyoming notes that “to date [Professor Goren] remains silent about whether he has changed his mind. But now that the trial is over, it is time for 032 him to provide the scholarly community an explanation about whether he has altered his views of the ossuary, of the scientific analysis of patina and varnish or what.” Perhaps by the time these words appear in print, Professor Goren will have obliged.

The second major prop in the government’s case was Joe Zias. What he had said was damning: He had seen the ossuary in a Jerusalem antiquities shop in the mid-1990s without the critical phrase, “brother of Jesus”! If this were true, the addition of these words had to be a modern forgery.

I first learned of Zias’s claim from Zias himself at the 2003 annual meeting of ASOR and SBL in Atlanta. I hesitated to print this claim based on a casual conversation. However, it turned out that Joe also told this story to Eric Meyers, who published Zias’s claim. Once Meyers published Zias’s claim (Meyers obviously believed Zias’s claim, which, if true, was clear proof of forgery), I felt free to publish it in BAR. I called the piece “Lying Scholars?”b

Since the judge’s decision in the case has come out, James Tabor of the University of North Carolina has confirmed that Zias had also told him that he (Zias) had seen the ossuary in an antiquities shop without the phrase “brother of Jesus.” I have talked to a prominent Jerusalem archaeologist who says Zias made this same claim to him. More importantly, Zias apparently also made this claim to the authorities, for they adopted this theory in the indictment; namely, that the ossuary itself is authentic and the first part of the inscription is authentic, but that Oded Golan added the final phrase “brother of Jesus.”

In the words of the criminal indictment: “Defendant No. 1 [Oded Golan] used an ancient ossuary … which bore an engraved inscription of ‘Jacob [James] son of Joseph.’ Defendant No. 1 added to this ossuary, either alone or with the assistance of others, the words ‘brother of Jesus’ in such a manner that these words were made to appear as part of the original inscription which had already appeared on the ossuary for two thousand years.”

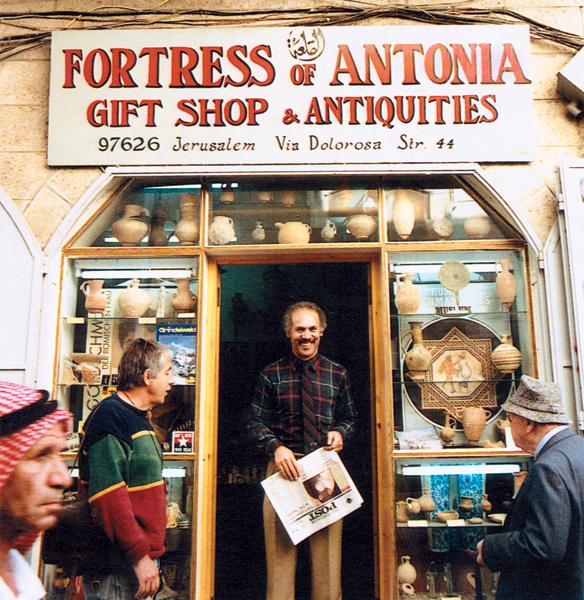

The antiquities shop that Zias identified as the one where he had seen the 033 inscription was on the Via Dolorosa, owned by a man named Mahmoud Abushakra. By the time the indictment was filed, Mahmoud Abushakra had closed his shop and moved with his German wife to a little village in Saxony, Germany. When I finally tracked him down, Abushakra told me that he had never had in his shop an ossuary with the inscription that Zias claimed to have seen there. Licensed antiquities dealers, of whom he was one, must keep an inventory of all items in their shop. To have this in the shop without including it in the inventory would have been illegal, not to say dangerous; the IAA had its inspectors coming around regularly to check his inventory. And this ossuary was not in his inventory.

Not long before the judge handed down his decision, Zias admitted that he was only joking when he told me (and presumably others) that “brother of Jesus” was missing from the inscription when he first saw it at Mahmoud’s shop; “having no sense of humor,” I took him seriously, he wrote in an email.c

At the trial, things turned worse. Zias admitted on the stand that he had never seen the inscription on the ossuary in Abushakra’s shop! Indeed, he could not read it even if he had seen it, he admitted. He explained that he was not an epigrapher; his specialties lie elsewhere. Where then did he learn of the inscription? Abushakra told him. That’s where he learned of the inscription that became the basis of the criminal indictment!

We have recently learned that indeed Abushakra did have an inscribed ossuary in his shop. But it was not the James Ossuary. Like the James Ossuary, however, it included Joe Zias’s first name, “Joseph,” which, alas, Zias could not read. Abushakra kept the Joseph Ossuary, as we may call it, with the inscription side to the wall and would show the inscription only on appropriate occasions. Abushakra originally put a price of $20,000 on it. When he could not sell it, he finally reduced the price to $5,000, perhaps when he was closing his shop. At this price, it was purchased by a private collector.

This was apparently the ossuary that Abushakra mentioned to Zias and that inspired Zias’s false claim that he had seen the James Ossuary without the words “brother of Jesus.”

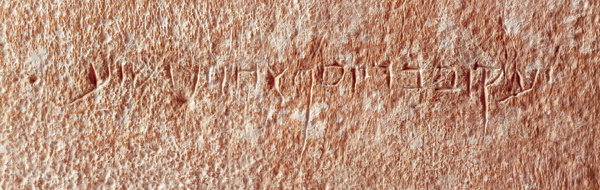

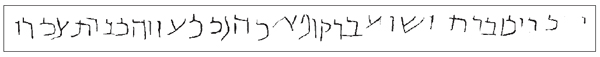

Robert Deutsch, a defendant who was cleared in the forgery case, has traced the Joseph Ossuary to a private collector who does not wish his name to be used. The Joseph Ossuary from Mahmoud’s shop now sits on a Tel Aviv balcony. Deutsch, a leading antiquities dealer and author of several scholarly books on artifacts and inscriptions in private collections, supplied us with a photograph of the Joseph Ossuary, which is being published here for the first time. The drawing of the inscription is by Ada Yardeni.

The inscription on the Joseph Ossuary reads: “Joseph, son of Judah, son of Hadas.”

Is It Jesus of Nazareth?

My bottom line is simply this: There is no reason to doubt the authenticity of the inscription on the James Ossuary. Whether it refers to Jesus of Nazareth remains a question.

A prominent statistician from Tel Aviv University, Professor Camil Fuchs, has attacked this problem,3 but the problem with statisticians is that they never give you a plain or easy answer. They talk only about probabilities expressed in percentages. As Fuchs tells us, a yes/no dichotomy is “beyond the purview of statistics.” He can give us only “an estimate of the ‘likely’ number of such individuals” named James with a father Joseph and a brother Jesus. And even these estimates are based on a number of assumptions.

Let me begin by giving you Fuchs’s (somewhat simplified) answer: There is a 38 percent chance that this is the only 062 instance of a James with a father named Joseph and a brother named Jesus in Jerusalem at this time. There is a slightly smaller chance (32 percent) that there were two such men named James in Jerusalem at this time. What’s the chance that there were three such people? Only 18 percent. Beyond three, there’s only a minute chance. In layperson’s language there were probably one, two or possibly three people with this name at this time. Expressed another way, with a confidence level of 95 percent, we can expect there to be 1.71 individuals in the relevant population named James with a father named Joseph and a brother Jesus.

Fuchs’s methodology is similar to that used in DNA testing: For each site on the DNA, the investigator determines the 063 064 relative frequency of the specific allele in the relevant population.

A number of assumptions underlie Fuchs’s estimates in addition to the size of the population of Jerusalem at this time. First, however, what is “this time”? Based on the published research regarding the period of time in which reinterment in ossuaries was practiced, Fuchs assumes it is the period between 6 and 70 A.D. (He always, as here, assumes “conservative” numbers.)

Fuchs assumes the ossuary came from Jerusalem because almost all known stone ossuaries were found there and Oded Golan says the antiquities dealer from whom he bought the ossuary said it came from Silwan, a village that is part of Jerusalem. The next step is to estimate the population of Jerusalem at this time (38,500 in 6 A.D., growing to 82,500 in 70 A.D.). Fuchs reduces this number because we are interested only in males; none of the women can fit the name profile we are looking for. Next, the James whose bones were placed in this ossuary was obviously a grown-up; therefore eliminate children who will not reach manhood from the population pool. Clearly, the bones belong to a Jew; therefore eliminate the non-Jewish population of Jerusalem (5 percent of the population).

Two other overlapping characteristics are relevant: Someone in the family must have been literate; otherwise why inscribe a name (or three names) on the ossuary? (Fuchs assumes a conservatively high literacy rate of 20 percent, more than the accepted figures in highly urban areas, to reflect the unique status of Jerusalem at that time.) And they must have been fairly well-off to be able to afford an ossuary (and a burial cave in which it would be placed). The distribution of the number of children in the families in that period of time was also factored in the equations.

All these factors figure in Fuchs’s computations of probability, often more subtly and in greater detail than I suggest. Fuchs also depends on some assumptions derived from L.Y. Rahmani’s catalog of ossuaries in the state collection.4 Of the approximately 900 ossuaries in the catalog, only 230 are inscribed. Moreover, as Rahmani points out, this “seemingly high proportion of inscribed ossuaries is, in many respects, misleading since plain, uninscribed ossuaries were either discarded by the excavators or excluded from the catalogue.” Fuchs estimates that no more than 15 percent of all ossuaries bore inscriptions.

A number of reasons account for the inscriptions on ossuaries—to express pride in the social standing of the family or the deceased, to console the bereaved or to allow later burial parties to identify the ossuary of the deceased when placing others in the burial cave. But why include the name of a brother? Only one other ossuary in the catalog lists a brother. Another ossuary inscription mentions the son of the deceased. As Fuchs sensibly observes, “There is little doubt that this was done only when there was a very meaningful reason to refer to a family member of the deceased, usually due to his importance and fame.”

Fuchs’s computations also depend on the frequency of the three names in the inscriptions in Rahmani’s catalog. Among the 241 male names on the ossuaries in the catalog are 88 different names. “James” (Yaakov in Hebrew) appears 5 times or 2.15 percent of the time; “Joseph” (and variations) appears 19 times or 7.9 percent of the time; and “Jesus” (Yeshua in Hebrew) appears 10 times or 4.1 percent of the time. Based on the frequency of these names among the 241 male names on the ossuaries in the catalog, the statistical probability of the three names appearing together is 0.006787 percent.

Fuchs concludes that the estimate for the relevant population includes 7,530 men, and the likelihood of someone named James with a father named Joseph and a brother named Jesus in this population is 0.0227 percent. That is, the estimate of the number of individuals in that population who bear the three names with this relation is 1.71. Expressed another way, there is a 38 percent chance that only one individual had this combination, a 32 percent chance that two individuals had this combination, an 18 percent chance that three individuals had it and an 8 percent chance that four individuals had it. And Fuchs can state this with 95 percent confidence.

That’s about as simple an answer as statistics can give us.

We thank Samuel and Tamar Fishman for translations of parts of the trial transcript and Judge Farkash’s opinion on which parts of this article are based.

In all the hubbub and flurry of the verdict last March in the “forgery case of the century,” one question—the central question—seems to have gotten lost: Is the ossuary inscription “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” genuine or not? And if it is, does it refer to Jesus of Nazareth? After all, “Jesus” was a common name at the time. These are enormously important questions to the world of Christianity, as well as to anyone else interested in the material world as it existed at the time Jesus walked this earth. As to the authenticity of the inscription, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Fudging with Forgeries,” BAR 37:06.

Hershel Shanks, “Lying Scholars?” BAR 30:03.

See Strata: “Joe Zias: ‘Hershel Has No Sense of Humor,’” BAR 38:03.

Endnotes

Eric Meyers, “Eric Meyers’ Reaction to the Verdict in the Forgery Trial in Israel,” ASOR Blog, March 14, 2012, http://asorblog.org/?p=1966.

A segment on 60 Minutes attempted to show that Marco was involved with another artifact that Oded Golan was also accused of forging, the 15-line Yehoash inscription. We questioned whether 60 Minutes accurately reported what Marco said in Arabic, but 60 Minutes refused to give us the transcript of its interview with Marco. See Hershel Shanks, First Person: “The Lion and the Flea,” BAR 37:03 and “

Camil Fuchs, “Demography, Literacy, and Names Distribution in Ancient Jerusalem—How Many James/Jacob Son of Joseph Brother of Jesus Were There?” Polish Journal of Biblical Research 4, no. 1 (December 2005), pp. 3–30.