052

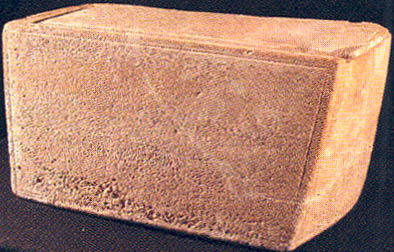

“By accident most strange,” Shakespeare reminds us in The Tempest, can come “bountiful Fortune.” So, it might be argued, was the case with the tragic accident in which the now-famous ossuary (bone box) inscribed “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” broke last fall on its way from Israel to Toronto for exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM).a It arrived in a cardboard carton encased only in layers of bubble wrap, which, when removed, revealed a soft limestone bone box that had broken into five pieces.

Now restored, the ossuary is more structurally sound than before. And the accident provided our team at the ROM with an opportunity to study the bone box and its inscription in ways that would have been impossible had the box not broken. The studies we conducted have convinced us that the ossuary and its inscription are genuinely ancient and not a modern forgery. This conclusion, of course, is consistent with the findings of leading Semitic paleographers and Aramaic linguists, as well as the Geological Survey of Israel, and contradicts those who assert that the inscription must be a forgery simply because it is “too good to be true” or because it surfaced on the antiquities market rather than having been found in a professional archaeological excavation.b

When we opened the carton and removed the bubble wrap, the pieces of the ossuary were still loosely held together. Once we received permission from the ossuary’s owner, Israeli antiquities collector Oded Golan, to mend the ossuary, Ewa Dziadowiec, our stone conservator, proceeded to lift the pieces apart so that the box could be reconstructed.

We were able to examine minutely the small shards that had broken away from the ossuary’s inside walls. These shards consist mostly of fragments of the thick encrustation that had built up in the bottom quarter of the ossuary, along with surface soil stains. The top of this encrustation was level with the markedly pitted surface on the lower exterior face of the inscription side of the ossuary, reflecting extremely damp, if not wet, conditions where the ossuary was once housed.

Even before shipment, the ossuary had a large crack that started below the inscription and ran around the side of the ossuary. The stresses of travel significantly 053extended this crack. This original crack on the inscribed face of the ossuary was also filled with encrustation. The deposit included tiny fossilized root fibers, an indication of damp conditions suitable for plant growth. (The root fibers were too tiny for plant identification, which might have given a clue as to the burial setting. Moreover, petrified roots contain no organic remains that can be dated by radiocarbon analysis.)

We used two different analytical techniques to look at the shards from the interior deposits. With Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), we examined the chemical composition of the encrustation. It was rich in phosphate, at a level much higher than that recorded for the exterior patinac as cited by the Geological Survey of Israel.d Phosphate is particularly characteristic of bone. Given the evidently damp condition of the ossuary’s interior, the original bones in the ossuary likely leached and the phosphate migrated, through capillary action, to the walls of the ossuary, where it re-crystallized as the phosphate mineral called apatite. This could also have occurred if someone had used the ossuary as a flower planter, as sometimes happened. Plant fertilizer is often high in phosphate. But the leached bone deposit is a far more likely explanation.

We subjected another tiny shard from the interior crust to a light-polarizing microscope examination. This involves embedding the sample in resin, cutting a thin sliver, and mounting this on a glass slide so that one can shine light through it and observe its composition. The sample had a small bit of the stone itself adhering to it where it broke away from the casket. The encrustation was built up in thin layers, each one slightly differently colored. The various colors likely reflect a different ratio of iron minerals present, but the amount was so negligible that the standard SEM analysis failed to register the difference. However, the distinct layering was quite visible under the polarizing light. The suggestion that the encrustation on the outside could have been artificially induced can be largely discounted. It is scarcely credible that anyone would exert so much effort even on the inside of the casket. And an artificially induced encrustation would normally be much more homogeneous in character (instead of layered, like this sample).

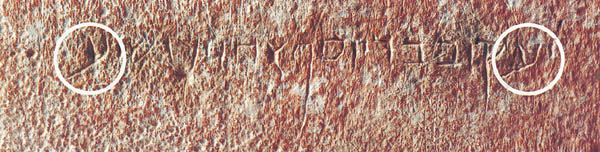

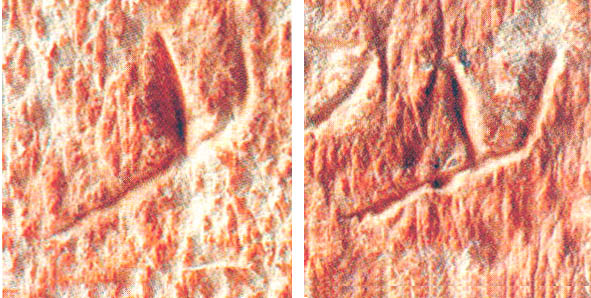

The ossuary was exhibited at the ROM for seven weeks last November and December, when nearly 100,000 people came to see it. After it came off display, the ROM team had an additional day to examine it. With a simple hand-lens magnifying glass, and a 60x microscope, we were able to show that the so-called “two-hand” 054theory was baseless. This theory maintains that the last two words of the ossuary, “brother of Jesus,” were added by a second hand to an already existing inscription that read “James, son of Joseph.”

Our examination showed that part of the inscription had been recently cleaned, a little too vigorously, with a sharp tool. And for some reason whoever did it cleaned the beginning of the inscription, but not the end. The cleaning had removed some of the surface encrustation from down inside the letters, but not all of it. Those letters on which a sharp tool had been used may even be judged to be slightly “enhanced”—they look sharper than those of the other part of the inscription. The end of the inscription looks softer and less angular—more like a cursive script, and therefore of more recent date. But the soft look is due to the survival of the encrustation on the part that had not been cleaned.

Daniel Eylon, an engineer from the University of Dayton, in Ohio, who is experienced in metal-fatigue analysis in the airline industry, has recently attained some notoriety on the Internet by claiming that what he calls “service marks” are interrupted on the first part of the inscription, thereby revealing the inscription to be a modern forgery. Eylon tells us that if something has been around for a long time, it gets scratched or nicked by being touched or moved. If someone deliberately adds something to the object, these scratch lines are interrupted. He finds support for his contention that the inscription is a modern forgery by the interrupted “service marks” or scratch line in the first part of the inscription. There, the marks stop at the edge of the letters. Therefore, this part of the inscription must be a forgery. (His claim, incidentally, is just the opposite of the “second-hand” contenders, who see the last part of the inscription, as 055opposed to the first part, as a forgery.) Eylon’s error, however, is that he did not take into consideration the differential effects of the recent partial cleaning of the first part of the inscription. The cleaning was done quite carefully and rigorously, with the result that the so-called “scratch lines” in the incisions of the letters in the first part were scrubbed away.

The last two words in the inscription have not been touched. On the Internet there has been some discussion as to what appears to some as a difference in the length of the letters at the two ends of the inscription. They may appear to be different, but the reality is that some of the letters were tampered with inadvertently.

Through a simple hand lens, our ROM team was also able to observe signs of the natural aging of the inscription. Minute lines run through the stone like very fine veins. This is because the stone is formed mostly of a dense and homogeneous mass of dead microscopic shell organisms (Foraminifera) so typical of a soft limestone chalk. But the deposits tend to be layered, allowing what can be called a “vein” to form in the matrix. These veins are formed of calcite crystals that are harder than the surrounding calcium carbonate. When exposed (as on the surface of the ossuary), the surrounding area erodes at a faster rate than the hard crystals in the vein, which is left as a “proud” line. Under magnification, the veins run consistently across the surface of the ossuary and through the incised letters of the inscription.

Though the hard parts and the soft parts in the stone have eroded differently, the weathering has nevertheless 070occurred at a uniform rate.

The clear implication is that (apart from the over-cleaning of part of the inscription) the inscription has weathered naturally, at the same rate as the adjacent parts of the ossuary.

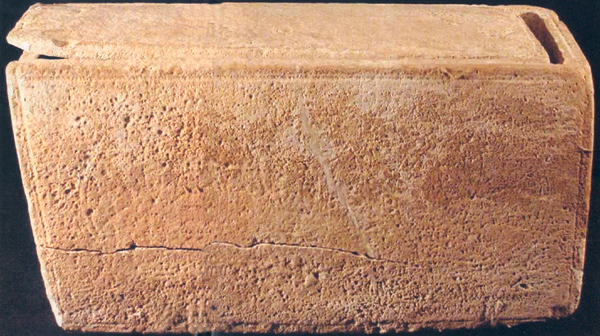

Originally—2,000 years ago—the ossuary was sanded smooth. Only on the inside can one see the faint, weathered traces of the chiseling used to cut the ossuary from a block of stone. Each side of the ossuary has been prepared with a groove around the edge that acts essentially as a frame. Similar grooves run along the raised lips that accommodate the sliding lid. Nothing in the frame tells us which is the back and which is the front of the ossuary. However, we were able to detect flecks of red paint on the side opposite the inscription and on the lid, indicating that these two surfaces had once been covered with red paint. In addition, on the side opposite the inscription, we found traces of a decorative design, typical of many other red-painted ossuaries. The design consists of three concentric incised circles containing compass-drawn, six-pointed stars, often called rosettes. Their traces are so faint, however, that they can be seen only when illuminated at an angle.

Some have suggested that the weathered design on one side and the comparatively sharp inscription on the other indicate a modern forgery. But there is no indication in the inscription itself or its weathering that would lead us even to suspect a modern forgery. The differential weathering may be accounted for by several other possibilities. The likeliest is that the build-up of encrustation and the comparatively well-preserved outline of the inscribed letters result from the fact that the ossuary was partly protected by being housed in a niche in the burial cave in which it lay. In this scenario, the inscription was on the back of the ossuary, protected from weathering by virtue of being covered in fallen dirt (but dirt that was damp at the bottom, where pitting occurred on the stone). Another possibility is that the ossuary had been previously used before the inscription was added. In this scenario, the ossuary with the bones of a family member housed in it may have lain for half a century or more in the damp conditions of a cave. This would have been enough to cause the surface of the ossuary to weather and the bones to disintegrate. The ossuary was then reclaimed and resold. At this point a new inscription was added on the undecorated “back” of the ossuary, and the bones of James were interred in it. But in either event it is clear that the inscription is not a modern forgery.

“By accident most strange,” Shakespeare reminds us in The Tempest, can come “bountiful Fortune.” So, it might be argued, was the case with the tragic accident in which the now-famous ossuary (bone box) inscribed “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” broke last fall on its way from Israel to Toronto for exhibit at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM).a It arrived in a cardboard carton encased only in layers of bubble wrap, which, when removed, revealed a soft limestone bone box that had broken into five pieces. Now restored, the ossuary is more structurally sound than before. And the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Hershel Shanks, “Cracks in James Bone Box Repaired,” BAR 29:01.

See André Lemaire, “Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus,” BAR 28:06, and Hershel Shanks and Ben Witherington III, The Brother of Jesus (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2003).

In archaeometry, “patina” refers to a surface appearance that develops from a reaction of the object itself to the environment; “encrustation” implies a deposit that settles on a surface through migration of soluble minerals, either from within the object itself or from elsewhere.

See “Epigraphy—and the Lab—Say It’s Genuine,” BAR 28:06.