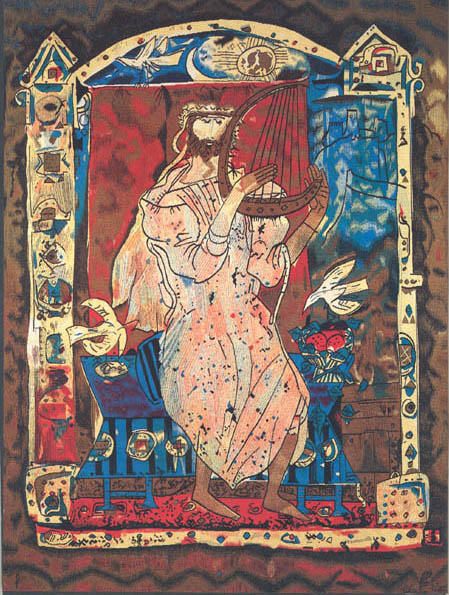

But Did King David Invent Musical Instruments?

He composed Psalms and played the lyre…

048049

While the dividing line between poetry and prose in the Hebrew Bible is imprecise, and the two types tend to blend into each other, especially in the prophetic writings, certain features that occur in both are more frequent and prominent in poetry than in prose. One of these is ellipsis, or the use of fewer words in poetry to say essentially the same thing that is said with more words in prose. In poetry, certain words, especially particles such as prepositions, conjunctions and the definite article, tend to be omitted whereas in prose they would be used. Put another way, there is parsimonious use of various words and particles in poetry (and less so in prose), so that some do double, instead of single, duty. The same term may be understood to qualify both parts of a clause or the halves of a typical line of Hebrew poetry. The possible presence of such double-duty terms in the text is a challenge to readers and scholars to ferret out the correct, or at least the more plausible, rendering of many passages in the Hebrew Bible.

In the last issue of Bible Review, I discussed an instance of a double-duty word in Isaiah. Commonly, in Hebrew as in English, the double-duty word is explicit in the first parallel word-unit and implicit in the second. In Hebrew poetry however the explicit use of a double-duty word may be found in the second word-unit and be implied in the earlier unit. If the translator misses this, he is in trouble, as I tried to show with the example from Isaiah.

Double-duty words can be and often are verbs adjectives, nouns or adverbs. But even more commonly, as I indicated above, they can be prepositions—and that is the case in the instance I want to focus on here.

The passage is from the eighth-century prophet Amos. Amos is condemning the wanton and dissolute behavior of government leaders in both Samaria 050and Jerusalem, and at the same time warning them solemnly that there is a day of reckoning in the immediate future for them and for the nations they rule and represent before God.

Chapter six is one of the “woe” passages, so-called because its predictions of disaster and devastation are introduced with the words “Woe to those who…” The “woe” form and formula are used by practically all the prophets, beginning with Amos and extending through both Old and New Testaments. The most elaborate examples are to be found in the prophecy of Isaiah (5:8–23) and in the Gospel of Matthew (23:13–36). This category or genre reflects the prophet in his role as a spokesman for God as judge of a rebellious nation or community, especially its leaders who are more culpable and blameworthy than ordinary citizens. Needless to say, human behavior over the centuries and millennia has always provided the prophets with ample material to justify the continued and extended use of this category of judgmental oracle.

Modern translations often abandon the use of “woe” For example, chapter six of Amos begins in the New Jewish Publication Society translation, “Ah, you who are at ease in Zion,” in contrast to the Revised Standard Version’s translation, “Woe to those who are at ease in Zion.” I like the latter better.

The New English Bible translates the line “Shame on you who live at ease in Zion.” “Shame” does not seem to me a satisfactory translation of the Hebrew hwy (pronounced

The prophet’s message is clear: Woe to Israel because of the dissolute, uncaring way it is living, without regard to the commands of the Lord; in the end, Israel will pay for its profligacy:

“Woe to those who are at ease in Zion, and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria…

“Woe to those who lie upon beds of ivory, and stretch themselves upon their couches, and eat lambs from the flock, and calves from the midst of the stall; who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp, and like David invent for themselves instruments of music; who drink wine in bowls, and anoint themselves with ther finest oils, but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph! Therefore they shall now be the first of those who go into exile, and the revelry of those who stretch themselve shall pass away” (Revised Standard translation, Amos 6:1–7).

Let us look more closely at verse 5:

“[Woe to those] who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp, and like David invent for themselves instruments of music…”

The first half of the verse (or colon, as the scholars call it) is relatively straightforward, although a few comments about it may be worthwhile. The instrument referred to (Hebrew: nabel) is not a harp—this is an archaic translation. It is really a lyre, as we know from many ancient depictions.a The Hebrew word translated “sing” (

Now let us turn to the second half of the verse:

“And like David invent for themselves instruments of music…” This is strange indeed. David is famous as a musician, specifically as one who played and sang. He also composed many psalms (and other songs). But where in any tradition is it ever suggested that he “invented” an instrument of music?

Some scholars have suggested that the phrase “like David” is secondary; that is, it was inserted by a later editor, but was not part of the original text.

To delete the reference to David seems to be an artificial way of solving the problem, but it is not a solution anyway: The first half of the verse makes it clear that the prophet is condemning orgiastic parties. The people addressed by this “Woe” are making music, either purely instrumental or accompanying their songs on a stringed instrument. But has it ever been shown that musical instruments were invented at parties, wild or otherwise? It is conceivable that some object or gadget might be used to produce musical sounds, but such contrivances would be trivial, transitory and entirely unsuited to the meaning intended here. And why would the prophet heap scorn on those who invent instruments of music? It is much more likely that his abuse is aimed at something else that they are doing, namely, at the words of the songs they are singing, since there is ample evidence that such songs were often obscene and even worse, blasphemous. The context shows that these people are eating and drinking to excess, behaving abominably, so the danger of committing some offense against the deity is really quite great, but inventing a new instrument would hardly qualify.

In pagan traditions, musical instruments are invented by gods or demi-gods, such as titans. In the Bible, credit is assigned to antediluvian patriarchs, for example, the descendants of Cain in Genesis 4:21. There is no other biblical tradition about the invention of musical instruments.

Despite the difficulty, almost every Bible translation sticks with what we might call this literal translation. None really understands the verse correctly. The New Jewish Publication Society translation footnotes the verse with the observation “meaning of Heb. uncertain.”b

The key to understanding the second colon of the verse lies in identifying the double-duty preposition that is explicit in the first colon and only implicit in the second. Strangely enough, this seems not to have been noticed before.

In the first colon, the people are condemned for strumming (literally) on or upon the mouth of the lyre. The preposition “on” or “upon” (Hebrew: ‘al) is implied, though unstated, in the same position in the parallel line in the second colon. It is a double-duty word.

Thus I would translate the second colon as follows: “and like David improvise [instead of invent] for themselves on or upon instruments of music.”

In short, Amos is charging the people with inventing or devising new songs, with instrumental accompaniment; and I think the implication is clear that the new songs are scurrilous, obscene or blasphemous, and possibly all three. Moreover, by recognizing the double function of the preposition, we restore balance and harmony to the verse, and come up with a picture of what is very likely to have happened at these parties and celebrations so much condemned by the prophet.

Both Hosea and Isaiah refer to similar drunken parties indulged in by the leadership in Samaria and Jerusalem (Isaiah 28:1–22, especially 1–13; Hosea 7:3–7), so the phenomenon is well attested. But nowhere to my knowledge is anyone in the whole history of Israel charged with inventing a musical instrument, least of all, David. Inventing songs is one thing, and quite common; inventing instruments is quite different, and when it happens, the context is hardly that of a drunken party.

Since the argument is based on the absence rather than the presence of something, the case can’t be proved, but by recognizing the use of a device, that is, the deliberate omission of a preposition, we may be closer to the intention of the prophet-poet, and thus better able to clarify an otherwise obscure and difficult saying. It may also save us from suppositions and presumptions about what was going on at the party in question, and even about David, the famous musician, that were never intended by the author. We do assume that the contemporary hearers and readers of these words understood very well what the prophet meant by his words, and if we can put ourselves in the place of those hearers and readers, then we have accomplished a principal purpose of translation and interpretation of the biblical text.

Since writing the above, Professor Freedman has discovered that there is a modern translation that renders the verse as proposed in this article. It is the American Bible Society translation called The Bible in Today’s English Version (1976), more popularly known as the Good News Bible. However, it is quite possible, Bible Review has learned, that Professor Freedman himself may have been the source of this translation. The first draft of the translation of Amos was prepared for the American Bible Society by Dr. Herbert G. Grether who recalls discussing problems in the translation of Amos with Professor Freedman, and “it is quite possible the suggestion came from him.” This is also Professor Freedman’s recollection.—Ed.

While the dividing line between poetry and prose in the Hebrew Bible is imprecise, and the two types tend to blend into each other, especially in the prophetic writings, certain features that occur in both are more frequent and prominent in poetry than in prose. One of these is ellipsis, or the use of fewer words in poetry to say essentially the same thing that is said with more words in prose. In poetry, certain words, especially particles such as prepositions, conjunctions and the definite article, tend to be omitted whereas in prose they would be used. Put another […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Bathja Bayer, “The Finds That Could Not Be,” BAR 08:01.