Can Archaeology Help Date the Psalms?

Footnotes

Ze’ev Meshel, “Did Yahweh Have a Consort? The New Religious Inscriptions from the Sinai,” BAR 05:02; Harvey Minkoff, “As Simple as ABC: What Acrostics in the Bible Can Demonstrate,” Bible Review 13:02.

Endnotes

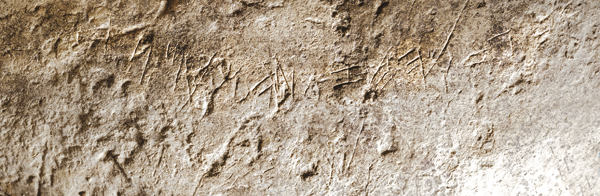

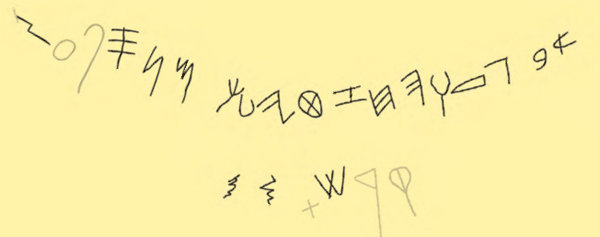

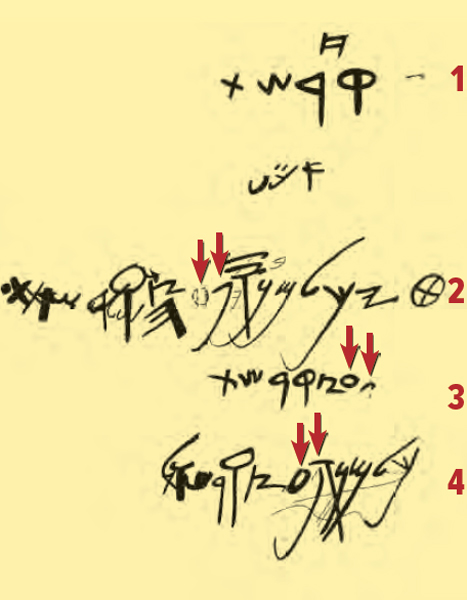

The Tel Zayit inscription is just an alphabet. The Izbet Sartah inscription comprises five lines. The first four are probably gibberish, a scribal exercise. The last line is an alphabet.

The following verses serve as divisions: 41:14 (English, v. 13), 72:18–20, 89:53 (English, v. 52), and 106:47–48.

The pe and ayin are not as clear in the Tel Zayit inscription as they are in the Izbet Sartah inscription. But the prevailing view is that there is a pe and an ayin in this order in the Tel Zayit inscription.

The suggestion that these verses need to be reordered was made long ago. See, for example, S.R. Driver, An Introduction to the Literature of the Old Testament, 4th ed. (New York: Meridian, 1892), p. 346.

With regard to chapter 25, this chapter parallels chapter 34 in that both chapters lack a verse for the letter vav (the sixth letter) and both add an extra pe verse at the conclusion of the acrostic. This makes it very likely that chapter 25 originally paralleled chapter 34 in its pe/ayin order as well.

With regard to chapter 37, this is an acrostic where the ayin section is missing. But the section for samekh (the previous letter) has an unusually large number of words and spans three verses, 37:27–29, while the sections for all the other letters span only one or two. Moreover, the Septuagint (the ancient translation of the Bible into Greek) has an additional phrase here, not found in the Hebrew. The most likely explanation is that there was once an ayin verse here, some of which has been picked up in the samekh section. Of all the 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet, why is it that the textual problem arises in the context of the ayin verse? Probability suggests that this is not mere coincidence, but that it has something to do with the issue of the pe/ayin order. Perhaps something went wrong in the course of the re-ordering of the original pe/ayin order to ayin/pe. Or perhaps at some point, a scribe accustomed to the later ayin/pe order was copying from a text which had the pe/ayin order, and jumped to the wrong line. I strongly believe that if the correct text of this chapter is ever established, it will end up being one in which the pe preceded the ayin.

Although many scholars have argued for an original pe/ayin order in chapters 9–10 and 34, none that I have seen have taken the next step and argued, as I am, that chapters 25 and 37 originally followed the pe/ayin order as well. Of course, without the archaeological evidence of the recent decades, they had no reason to suspect that this might be the case.

Émile Pueche claims that a certain eighth century B.C.E. inscription from Lachish follows the ayin/pe order. But André Lemaire rejects Pueche’s readings as unsubstantiated. See David Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994), vol. 4 (Tel Aviv: Yass Publications in Archaeology, 2004), pp. 2116–2117.

The acrostics of chapters 2, 3 and 4 of the Book of Lamentations follow the pe/ayin order. Although the acrostic in the first chapter in the received text follows the ayin/pe order, the text of the first chapter found in the Dead Sea texts follows the pe/ayin order. Surely the Dead Sea text reflects the original order.

The Book of Lamentations was likely composed between 586 and 538 B.C.E. None of the hope engendered by the proclamation of Cyrus is reflected in it.

In the two earliest manuscripts of the Septuagint of Proverbs 31:10–31 (Vaticanus and Sinaiticus), the translation of the pe verse precedes the translation of the ayin verse. These manuscripts were copied long ago, in the fourth century C.E. This suggests that there was a very old Hebrew text with the pe/ayin order.

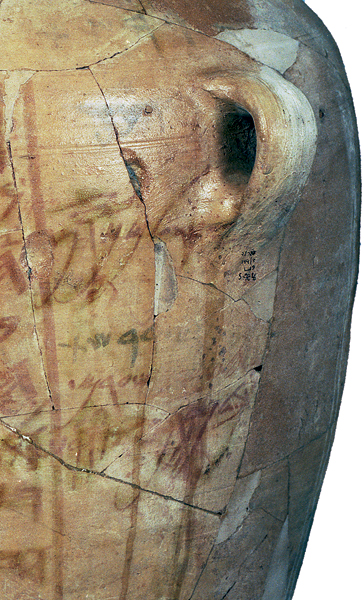

See Martin Heide, “Impressions from a New Alphabetic Ostracon in the Context of (Un)Provenanced Inscriptions: Idiosyncracy of a Genius Forger or a Master Scribe?” pp. 148–182, in Meir Lubetski, ed., New Seals and Inscriptions, Hebrew, Idumean and Cuneiform (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2007). Although the ostracon is unprovenanced, the prevailing view is that it is genuine. Allegedly, it came from the debris of the Temple Mount.

The acrostic that runs through chapters 9 and 10 is missing seven of the 22 letters; the acrostic of chapter 25 is missing kof, and includes resh twice; and the acrostic of chapter 37 is missing ayin.

In contrast, the acrostics in the fifth book are almost perfectly preserved. The acrostics of chapters 111 and 112 are complete, and the acrostic of chapter 119 is complete, with every letter repeated eight times! The lone possible imperfection is chapter 145 which lacks a nun verse. But the fact that all the other acrostics in the fifth book are complete suggests that the nun verse is not missing here, but was omitted intentionally. The nun verse found in the Dead Sea and Septuagint texts of Psalm 145 should be considered a later addition. The nun verse found in these sources is suspicious for other reasons as well.

That there was a reordering of chapter 145 also seems unlikely because the ayin and pe lines of chapter 145 seem to have a parallel at Psalms 104:27–28.

In the surviving provenanced Hebrew inscriptions from the eighth through sixth centuries B.C.E., it has been observed that when samekh is immediately followed by pe, the two letters are consistently written the same way. Based on this, it has been suggested that Israelite scribes in this period were trained in an order in which samekh was followed by pe See Ryan Byrne, “The Refuge of Scribalism in Iron I Palestine,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 345 (2007), pp. 4–6. Thus, the pe/ayin order may now be supported by a different line of evidence.