The familiar, the quotidian, the unexalted—these are the subjects of George Segal’s most famous sculptures. The American artist’s best-known works may be mentally arranged as a walk through a typical small city—out the front door of a diner onto the street corner, down the road past the gas station, the dry cleaner and the park bench, up a narrow staircase to a cramped apartment, along the corridor into the bathroom, and eventually into the bedroom. There is a Segal work for each of these places.

But what happens when Segal’s mind and eye are turned loose on the most mythological, the most exalted, the most timeless of all texts—the Book of Genesis?

In the past half century, while working on his now-famous scenes of American life, Segal produced a series of much less familiar works based on the first book of the Bible—dramatic scenes inhabited by plaster figures of Adam and Eve, Abraham and Isaac, and other figures from Genesis.

The point of contact between George Segal and the Book of Genesis is anonymity, the point at which a nameless nobody can stand for a nameless everybody. In Segal’s sculptures, this anonymity derives from his signature artistic style. Segal’s work is dominated by life-size white plaster and bronze figures arranged in real-world settings. In The Diner, from 1964, perhaps his most familiar work, a plaster cast of a man slumps on a stool, waiting for the waitress behind the counter to pour his coffee (see George Segal’s The Diner). The sculpture reverses the standard relationship in Western portraiture between figure and ground. With most portraits, the figure is full of color, detail and personality, while the background is a distant landscape, a generic interior or a simple plane of color. Think of the fantastic landscape behind Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, the sedate generic interior in which Whistler’s mother is seated or the deep blue monotone behind the resplendent Henry VIII in Hans Holbein’s portrait. Henry VIII is definitely somebody; the tone behind him is nothing.

In contrast, Segal makes the ground, or setting, specific and the figure generic. It is the diner that is real, with its real counter, real circular stool, real stainless steel coffee urn, real sugar jar and real napkin dispenser. We focus on these inanimate objects as we would not do in everyday life. In contrast, the man and woman separated by the counter are colorless and shapeless, with their features blurred to the point that they are nobody—and therefore can represent anybody. By stripping identity from the animate subjects in The Diner, Segal invites us to project ourselves upon the figures in a way that would be impossible were they individually recognizable.

When you gaze at Whistler’s painting of his mother, you don’t imagine what it would be like to be sitting in her black rocking chair, knowing that you had given birth to the famous artist. But when viewing Segal’s The Diner, you do, if you happen to be a man, imagine yourself looking at that woman. And if you are a woman, you imagine yourself being looked at by that man. Through his reversal of the usual relationship between the color and concreteness of figure and ground, Segal draws us subtly but irresistibly into his work.

But what happens when the setting is not a modern city, but the world of the Bible, and the characters are no longer contemporary nobodies, but the cast of Genesis?

As critics starting with Erich Auerbach have observed, Genesis is a drama set on a stage without scenery and performed by actors without costumes. An offstage narrator provides the audience a few basic facts. Thereafter, everything is done by lighting—different actors having, successively, their moment in the spotlight—and by dialogue.

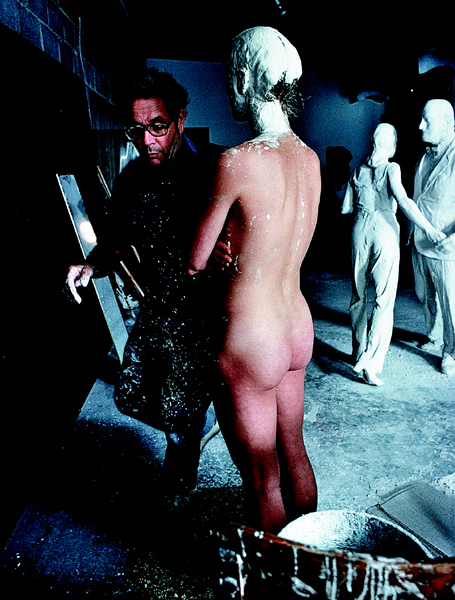

Segal is a director of sorts, who casts his characters in two senses of the word. First, he casts them by choosing them for the roles he wants them to play. Second, he literally casts them in plaster. After or perhaps while casting them in both these ways, he blocks them theatrically—that is, he decides who will stand at what distance from whom, who will look at whom, who will touch whom and—far from least important—who will be illuminated by spotlights and how the light will fall on the figures. Segal’s very sparsely furnished, spotlighted and more or less monochromatic realizations of scenes from Genesis evince a deep, natural sympathy with comparable features in the biblical text.

In almost all of Segal’s biblical works, the human figures have been produced by his singular method of wrapping models in plaster-saturated cloth and allowing the cloth to harden while still on the model. This technique yields figures that are undeniably individuated and yet must be described as realized rather than idealized. They are somebodies, but they are nobody you or I know. Segal does not wrap the famous. His models are actors of a special sort, to be sure, lending their faces and poses for the purposes of his artistic tableaux, but they are amateur actors. In Segal’s nonbiblical works, they usually portray themselves. In his biblical works, by contrast, these same plain folks are called on to portray the legendary or mythical figures of Genesis.

How well do they succeed in their portrayals? In my opinion, they fail, but their failure becomes a deeply affecting aesthetic effect in its own right. The fail when they fall out of character—but Segal wants them to fall out of character and trusts them most when they do. Describing the effect of plaster-wrapping on his models, he once said:

The discomfort to the person is of such a nature that they can’t pretend with me; they have to relax, and they’re just as stoic and brave, or screaming and hysterical as they really are. It’s very hard to be a fake with that kind of wet discomfort over such a long period of time. Maybe I’m a sadist, I don’t know. But then I’ve also done the same person over six or seven times, and I’ve been absolutely amazed to find that even slight differences in state of mind come through that I can’t control in the finished sculpture.1

Now, models who cannot pretend, to use the word Segal uses, also cannot perform. But if they cannot perform, then they cannot portray. They cannot stay in character as Adam or Eve or Abraham or Isaac. They can only be themselves posed as Adam or Eve or Abraham or Isaac. However, that very distance between the real person and the posed personage creates a pathos all its own. This is the effect produced by a passion play in a Mexican village where a humble campesino is given the impossible role of Jesus on the cross. The peasant’s failure to be equal to the role becomes an act of homage, almost an act of worship. So it is also with the failure of Segal’s models, even when frozen into sculpture, to disappear into the characters whom they represent. They become everyman and everywoman humbled by the power of the myth.

In his work The Expulsion (1986–1987), Segal seizes upon a moment described in Genesis 3:24 in which the Lord God “drove the man out, and stationed east of the garden of Eden the cherubim and the fiery ever-turning sword, to guard the way to the tree of life” (see George Segal’s The Expulsion). (The text says that the Lord God drove the man out but doesn’t mention the woman; a few verses later she is found in bed with him, so evidently she followed dutifully after. Subordination of wife to husband is a part of what can with full justice be called the fall of woman.) The scene is, of course, a familiar one in Western religious art. What distinguishes Segal’s expulsion from all others that I know of is the blocking: Adam and Eve walk not past us but directly toward us, hiding their shame from us with fig leaves and implying by their direction that we are already in the exile to which they have just been banished. Once again, the statues in the foreground are stone gray and the color is found in the background. Segal has made their paradise seem itself a kind of inferno by turning the fiery sword that prohibits their return to Eden (Genesis 3:24) into an entire wall of flame. Are they escaping a heaven that was actually a hell?

Segal produces a subtler effect, however, through his use of our cultural familiarity with this story. We may not know all of Genesis quite as well as we know American diners, but we know this part of it. The artist need not explain why this couple has such a downcast air. We know why. We recognize these sad sinners. They are our parents.

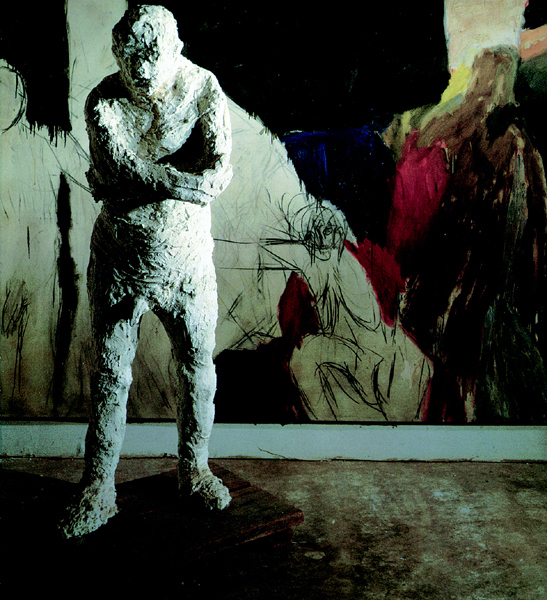

The Legend of Lot, a work completed in 1958, captures a much less familiar moment—a moment that the Bible passes over in silence, although it must have occurred (see photo, above). After the destruction of Sodom, the Book of Genesis recounts, Lot and his two daughters settle in the hill country. Fearful that they will be left childless, the daughters secretly plot to commit incest with their father. The elder sister urges the younger: “Our father is old, and there is not a man on earth to consort with us in the way of all the world. Come, let us make our father drink wine, and let us lie with him, that we may maintain life through our father” (Genesis 19:31–32). On two successive nights, the daughters commit incest with their father. Each time, the text says, “he did not know when she lay down or when she rose” (Genesis 19:33, 35). The offspring of these incestuous unions are the Moabites and the Ammonites, Israel’s neighbors across the Jordan River. The story of their origin in depravity and sin may well have been written to express the contempt that the Israelites felt for their cousins. But if that is the political meaning of the story, there is also a painful psychological meaning, for the story of Lot and his daughters is a story about the sexual aggression of young women and the sexual vulnerability of old men.

This is not a pretty subject in art—or a popular one. Nor is it a polite or correct subject—not in 2000 or, for different reasons, in 1958, when it was made. Therein lies the audacity of the artist.

The Book of Genesis does not trouble to tell us what Lot said or did when he came to, how he felt when he staggered into the daylight, hung over and struggling to remember what he had done or what had been done to him during those dark nights. This is the dreadful awakening that Segal dares to portray. His work is thus visual midrash, in the Jewish tradition of commenting on and revising the biblical text by selectively expanding it. Portrayed in this moment, Segal’s Lot is, to be sure, a harshly simplified old man, but then the Lot of Genesis is morally and psychologically simplified with equal harshness. The one work of art, as a result, brilliantly confronts the other.

In a later, more literal, and to my eyes less successful sculpture, Segal chooses to portray the act of incest in progress. But the earlier sculpture shown here consists of just one sculpted figure, a crude white plaster statue of the stooped old man standing nude, bewildered and ravaged. His daughters and their crime are suggested rather than portrayed in the semi-abstract, boldly colored canvas behind him.

The powerful effect of this work depends on the moving anonymity—the identity erasure, as we might put it—of its central figure. Lot, unlike Adam and Eve, is not a well-defined plaster cast of a man, but a coarse mannequin. Of the works pictured on these pages, only The Legend of Lot has this kind of anonymous, half-formed, half-deformed, utterly de-individualized figure at its center.

I recently called a friend, a Jewish man about 65 years old, and happened to get his visiting brother on the telephone. A moment later, when my friend took the phone, I said, “You and your brother sound amazingly alike.” “Yes,” he said, “and you know what? We’re getting to look alike too. You ask me, young Jews all look different, but old Jews settle into about six physical archetypes. Sam and I are sinking into the same one.”

I think my friend understates the matter. All old people of whatever ethnicity grow more alike over time. Old blacks and whites look more alike than young blacks and whites. Old men and women look more alike than young men and women. The men get breasts; the women lose them. The women get deeper voices; the men get higher voices. The male beard slows; the female beard speeds up. This conformity by slow collapse, about which we laugh in public and cry in private, I think of as the anonymity of the aged.

And as for the sexuality of the anonymous aged, well, I am reminded of a poignant phrase from Saul Bellow: “That shaggy nudity we know so well,” he called it in Humboldt’s Gift. In Segal’s The Legend of Lot, it is surely not by accident that the penis of the title figure has more definition than the face. Lot’s daughters were not interested in Lot because he was Lot, their father, but because he was male. His penis defined him for them.

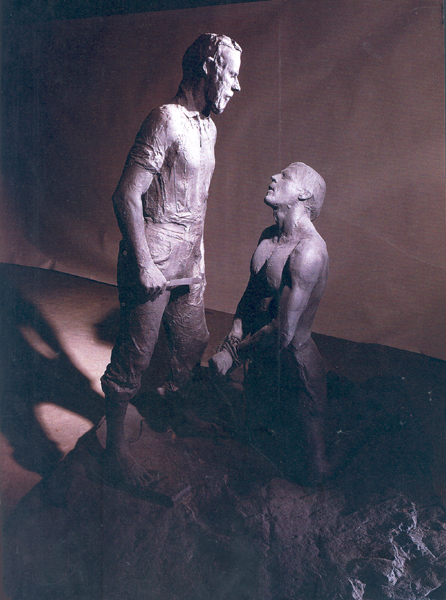

Two chapters after the story of Lot, in Genesis 22, God demands that Abraham sacrifice his beloved son Isaac, and Abraham goes so far as to bind Isaac on the sacrificial altar as an animal would be bound whose throat is to be slit before the ritual burning. Abraham has his knife drawn, apparently ready for the slaughter, when the voice of an angel—in effect, the voice of the Lord—is heard from heaven telling him to desist: “Do not raise your hand against the boy, or do anything to him. For now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your favored one, from me” (Genesis 22:12).

In 1978, when a Cleveland foundation, the Mildred Andrews Fund, commissioned Segal to sculpt a memorial to the four students killed during the infamous Kent State massacre of 1970, Segal chose to freeze the action at the moment just before the angelic voice is heard (see photo, above). When the work was completed, Kent State University officials refused to install it. As one of them later explained to a reporter in the September 11, 1978, issue of Newsweek: “An apparent act of violence [is] inappropriate to commemorate an act of violence…We’re trying to do what we can to establish a tranquil atmosphere.” Though Kent State had originally supported the artist’s choice of theme, the school’s officials proposed after the fact—that is, after Segal had completed this sculpture—that he sculpt the figure of an armed soldier: “Facing [the soldier] in gentle opposition [would be] a female contemporary. She could be nude or semi-nude to suggest vulnerability.” Needless to say, Segal rejected this sappy suggestion. To its great credit, so did the Mildred Andrews Fund, commenting, “The kids are dead, and you can’t spread honeyed wings over that.”

Today some viewers continue to have a negative reaction to this work. What they object to in it is evidently what the Kent State officials also objected to—namely, that Isaac, rather than Abraham, seems to be the hero of the piece. To the university officials, Isaac seems something of an affront to Jewish tradition. Segal’s Abraham does not seem to be “our father, Abraham,” ’Avraham ’avinu, with the streaming beard, massive physique, flowing robes and noble bearing that become a patriarch. The unidealized, unidentified, yet undeniably contemporary man seems small (if Segal’s Isaac stood up, he would be inches taller than his father). He even seems a pinched man, and perhaps—though who can tell?—an angry man.

The truth is, however, that Segal’s casting of Isaac as the hero of the episode, though it does change the emphases of Genesis 22, is fully in accord with postbiblical Jewish tradition and at odds only with Western iconographic tradition, which is to say Christian tradition. Jon D. Levenson, a professor at the Harvard Divinity School, has brilliantly demonstrated how Jewish attention—as evidenced in midrash and commentary—shifted over time from Abraham and his faith in God to Isaac and his trust in both his father and his God, not to speak of Isaac’s courage in facing death by the will of the one and the hand of the other.2

Levenson believes that this episode began as a legend about an actual child sacrifice, presumably in honor of the Phoenician deity Molech,a and was rewritten to imply Israel’s later ban on child sacrifice. But the central moral of the story was not that ban. Rather, it was a warning that unless Israel kept faith with the Lord as Abraham had done, the Lord might indeed turn on them. The story thus fit the dominant Israelite interpretation of the Babylonian conquest as a punishment for Israel’s breach of faith. In later centuries, however, beginning under Greek rule, Israel was made to suffer precisely because the nation had indeed kept faith with the Lord. Under religious persecution, Israel recognized itself more in Isaac’s plight than in Abraham’s. The challenge was to believe that God was not punishing them for their sins. Over the centuries, as virtually every generation (bekol dor vdor) faced this challenge, the stature of Isaac in the interpretation of the Akedah loomed ever larger. Isaac, in these later Jewish texts, is an adult, and he willingly lays himself on the altar.

The common iconographic representation of Abraham as a larger-than-life father is a revisioning of the near sacrifice in terms of the Christian account of another Father who is willing to sacrifice his Son. Reading the crucifixion through the Akedah, Christianity identified Isaac with Jesus, an identification that had the secondary effect of fusing Father Abraham with God the Father. Yet, as Levenson points out, in the Christian story God the Father actually completes the awful sacrifice. To an extent, then, we may say that whenever Abraham looms huge and godlike in the imagination, the imagination is Christian, while whenever he shrinks somewhat and Isaac grows larger, the imagination is Jewish.b In this sense, Segal’s imagination is thoroughly Jewish.

But is Segal’s tense, somewhat wiry Abraham an angry man?c The sculpture does not answer that question, but, I stress, neither does the text. In Genesis 22, Abraham gives no formal assent to God’s command, “Take your son…and offer him as a burnt offering.” Abraham never says “yes, my lord, if it please you” or the equivalent. From the beginning to the end of the story, Abraham never addresses a single direct word to God, and we cannot infer from his silence what his mood may be as he prepares for the sacrifice. Nor can we infer whether Abraham would actually have performed the final action had the angel not stopped him.

This riveting ambiguity in the text is wonderfully mirrored in the posture of Segal’s Abraham. The man seems at least stern and perhaps angry, but with whom? Surely not with Isaac, whom God himself has described as Abraham’s “favorite,” whom he “loves.” If Abraham were in fact about to proceed with the sacrifice, would there not be anguish on his face, mirroring the dismay we see on Isaac’s face? If there is anger on his face, is the anger not more plausibly directed toward God? And is Abraham about to plunge the knife into his son’s body, or is he rather about to fling the weapon defiantly to the ground? In the Bible, God steps in and ends the trial hastily at just this point, praising Abraham for his willingness to do what Abraham has never declared himself willing to do. By stopping the action at the same point and posing the father and son as he does, Segal captures just the subversive and suspenseful ambiguity of the original.

The ambiguity of Segal’s Abraham and Isaac contrasts strikingly with the fearsome clarity of Rembrandt’s 1635 The Angel Stopping Abraham from Sacrificing Isaac to God. In that iconographically influential masterpiece, Abraham is a giant of a man. With his huge left hand, he has wrenched his son’s chin up and back as a butcher does when slitting an animal’s throat. Clearly the ritual murder is well in progress, and Isaac has been saved only by the physical intervention of the angel of the Lord, who has just stricken the knife from the murderer’s hand. Rembrandt portrays the knife in mid-air and Abraham’s wrist still in the angel’s arresting grip. Isaac, pale of body and naked but for a loincloth, resembles no one more than he does the slain Christ.

I believe that the same young model who portrays Isaac in Abraham and Isaac portrays Jacob, sleeping under the stars on his first night away from home, in Segal’s Jacob and the Angels, from 1984–1985 (see photo, above). Having cheated his brother, Esau, out of his birthright, young Jacob is en route to Paddan-Aram, where he is to find himself a wife. Lying beside the road, with only a rock as his pillow, Jacob dreams of a ladder reaching to heaven: “A stairway was set on the ground and its top reached to the sky, and angels of God were going up and down on it. And the Lord was standing beside him and He said, ‘I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac: the ground on which you are lying I will assign to you and to your offspring…Remember, I am with you; I will protect you wherever you go and will bring you back to this land’” (Genesis 28:12–15). In Segal’s rendition, a single blue angel, in the shape of a voluptuous young woman, represents the heavenly figures ascending and descending the ladder.

In a 1996 interview with Nancy Berman, director of the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles, Segal said that he was attracted to the Jacob’s Ladder story because it is the story of a materially rich man who “all of a sudden has an aesthetic experience, a dream of spirituality.”3 But Jacob’s wealth actually comes much later, after many years of labor on his uncle Laban’s lands. I believe that this early dream is actually the dream of a religiously cynical young man who unexpectedly has a genuine vision of God.

Why do I call Jacob religiously cynical? When Jacob masqueraded as his brother, Esau, and offered goat meat to his father, Isaac, claiming that it was game that he had bagged, Isaac, deceived, asks Jacob: “How did you succeed [in the hunt] so quickly, my son?” The cynical Jacob answers, “Because the Lord your God granted me good fortune” (Genesis 27:20). “Your” God, not “my” God.

Jacob builds his entire early career upon such deceits, and yet he is not beyond redemption. Whatever his faults, Jacob is open to religious experience. Awakening from his dream of a ladder to heaven, he cries out, alone and with no one but himself to impress: “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the abode of God, and that ladder is the gate of heaven.” He calls the place Beth-El, “the House of God,” and erects his stone pillow as a witness to his covenant with God (Genesis 28:17–22).

And so, Segal leads us from the nightmare of the expulsion from Eden to a stairway to Heaven. This sculptor, so unflinching in his portrayals of loss, depravity and anger, shows us his ability to dream a cosmic dream of beauty and glory. His sculptures allow us to wonder just as Jacob’s dream made Jacob wonder.

This article is based on a lecture delivered on May 1, 1997, during an exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, which brought together for the first time five of George Segal’s biblical works.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

The deity Molech is thought to be related to the Phoenician cult of child sacrifice. See Lawrence E. Stager and Samuel R. Wolff, “Child Sacrifice at Carthage—Religious Rite or Population Control?” BAR 10:01.

On the Akedah in Jewish and Christian art, see Robin M. Jensen, “The Binding or Sacrifice of Isaac—How Jews and Christians See Differently,” BR 09:05; and Jack Riemer, “The Binding of Isaac: Rembrandt’s Contrasting Portraits,” BR 05:06.

For more on Abraham’s character, see the following articles in BR: Lippman Bodoff, “God Tests Abraham—Abraham Tests God,” BR 09:05; Philip R. Davies, “Abraham & Yahweh—A Case of Male Bonding,” BR 11:04; and Larry R. Helyer, “Abraham’s Eight Crises,” BR 11:05.