020

021

News of our exclusive cover story in the last issue about the bone box inscribed “James, the son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” has reverberated around the globe. The day after we released the issue of BAR, the bone box, or ossuary, was featured in color on the front page of the New York Times. Articles about the ossuary appeared on the front page of the Washington Post, the International Herald Tribune (with a picture of BAR’s cover) and almost every other newspaper in the world. The Jerusalem Post ran an extensive question-and-answer interview with the editor of BAR. We were on ABC, NBC, PBS, CNN, etc., etc. Lengthy stories appeared in Time, Newsweek and U.S. News and World Report.

With the permission of the Israeli owner of the ossuary (who was then still nameless), the Biblical Archaeology Society (the publisher of BAR) arranged to have it exhibited at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum in November, when our Fifth Annual Bible and Archaeology Fest would be held in Toronto. A number of other societies would also be holding their annual meeting there at the same time—the Society of Biblical Literature, the American Academy of Religion, the Near East Archaeological Society and the American Schools of Oriental Research. The ossuary’s owner asked the Israel Antiquities Authority for permission to send it to Canada for the exhibit, which was quickly granted.

Then tragedy struck.

The ossuary arrived in Canada cracked. The reaction we all had was summed up in the headline that blared in 72-point bold-face type from the front page of the Sun, Canada’s leading tabloid: “Oh, My God!”

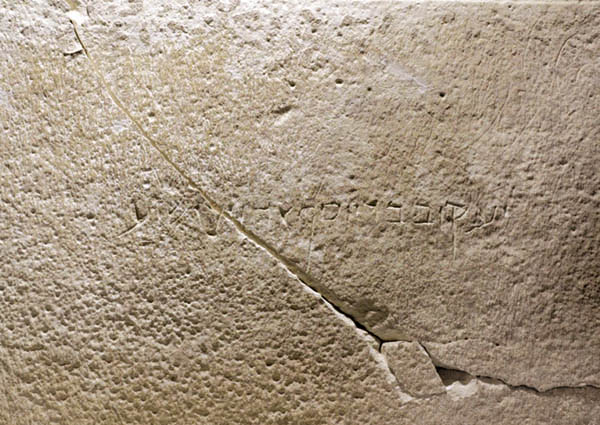

One of the new cracks ran directly through the inscription—just before the name of Jesus.

How did it happen? Some at the Royal Ontario Museum and elsewhere felt it was poorly packed—in bubble wrap and a cardboard box. The owner of the ossuary, who had arranged for the shipping of the ossuary, insisted that he had engaged the leading company in Israel for such purposes (Atlas/Peltransport Ltd.), a company with extensive experience in packing museum objects. Others wondered why Brinks, which handled the transit, sent the ossuary first to New York, where it was unloaded and then loaded onto another plane, then to Hamilton, Ontario, where it was unloaded from the plane and loaded onto a truck, and then transported to Toronto, instead of shipping it on a non-stop plane to Toronto. Others wondered whether the new cracks in the limestone box had developed because of the sudden drop in temperature in the hold of the plane as it climbed 30,000 feet into the air.

The good news was that the Royal Ontario Museum had on its staff an expert in the conservation and restoration of stone objects, Ewa Dziadowiec, who could conserve and restore it in a matter of days—in time for it to go on exhibit, as planned, on November 16.

The bad news was that the insurance company for five long days would not get an adjuster out to examine the damage and permit the conservation and restoration process to begin. Finally, however, an adjuster from New York was flown in; he examined the damage and permitted the ossuary to be conserved and restored. Dziadowiec completed the restoration in several days. The cracks were barely visible and the ossuary was structurally sounder than it had been when it left Israel.

The ossuary itself may have been damaged, but not its significance. If it truly once held the bones of James, who is identified in the New Testament as the brother of Jesus, it is the earliest archaeological attestation of three important figures—Jesus, James and Joseph—in the history of Christianity. Indeed, it is the first—and only—appearance of Jesus in the archaeological record of the first century A.D.

But the story continued to develop.

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) was reportedly disturbed because it had issued an export permit for the ossuary without realizing its significance. The owner had called attention to the content of the inscription on the ossuary and gave the ossuary a value of $1 million, 022but the officials at the IAA nevertheless failed to realize that the inscription might refer to Jesus of Nazareth (just as the owner had failed to realize it in the many years he had owned it). Indeed, no one realized its significance until the owner showed a picture of the inscription to Sorbonne paleographer André Lemaire, who wrote the BAR article. (“Burial Box of James the Brother of Jesus,” BAR 28:06)

Erroneous stories soon appeared in the papers that the Israeli police had called the owner in for questioning regarding his ownership of the ossuary. Then an Israeli newspaper, Ha’aretz, published a story revealing the owner’s name, with a paparazzo photograph of the owner outside his apartment. Instantly, the whole world knew his identity—Oded Golan, a 51-year old Tel Avivian whose cherished privacy has now been lost forever.

Lengthy articles about Golan soon appeared in Ha’aretz and another Israeli newspaper, Ma’ariv, as well as in such papers as Canada’s Globe and Mail.

Golan describes his collection as “most probably the largest and most important privately-owned collection of its kind in Israel.” He has been collecting for more than 40 years. When he was only nine years old, he discovered a cuneiform tablet in an archaeological dump. As a youngster he developed a relationship with the illustrious Israeli Biblical archaeologist Yigael Yadin, who invited the then-11-year-old boy to participate in Yadin’s dig at Masada. Today, Golan is a successful engineer, entrepreneur, businessman and a near-professional pianist. A white baby grand piano surrounded by wall cases of stunning ancient artifacts sits in his apartment in a middle-class Tel Aviv neighborhood.

According to Israeli law, if the owner of an antiquity purchased it before 1978, there is no legal problem regarding his right to own it. But if he purchased it after that date, he must be able to show a receipt for the item from a licensed antiquities dealer (who in turn must have a record of where the piece came from). If the owner cannot produce such a receipt, the piece is subject to confiscation. A question was soon raised as to when Golan acquired the ossuary.

At this point, BAR became involved. Based on what Golan had told us, we told the press that he had had the ossuary for about 15 years. Golan now maintains that he gave this as the number of years he had had the ossuary in his apartment—it was there for about 15 years. Perhaps, when we initially talked to him in his apartment, we asked him how long he had had the ossuary there. He states that he actually purchased the ossuary in the early-to-mid-1970s, when he was a young man living with his parents. When he moved into his own apartment, he took the ossuary with him. That was about 15 years ago. When his collection became so large that all of it could not be accommodated in his apartment, he placed part of the collection in storage. As he told the reporter for the Globe and Mail, “At the age of 23, it was an important piece, but at the age of 43 it was one of the least important pieces, 023and it went into storage.” It was in storage when André Lemaire first visited Golan. He showed Lemaire only a photograph of the ossuary and its inscription. When Lemaire saw the photograph, he immediately recognized its potential significance and asked to see the stone box itself.

If Golan acquired the ossuary only 15 years ago, the state may have a claim to it. If he purchased it more than 25 years ago—in the mid-1970s—the purchase would go back to before the critical 1978 date. Golan claims that many people—his old girlfriends and friends of his parents—saw the ossuary in his parents’ apartment and that they can testify to its being there at the earlier date. The Globe and Mail story found the explanation a bit bizarre, but added that “he related it with such unrestrained enthusiasm and lack of defensiveness” that it was entirely believable.

Another emerging legal problem involves the insurance. How much has the monetary value of the ossuary been reduced as a result of the alleged negligent handling of it during packing and transit? The legal test requires a determination of how much a willing buyer would pay a willing seller before and after it was damaged. The difference between the before-and-after fair-market value is the amount of the damage. There is some indication that the insurance company may claim that there was no monetary damage. This is not like a beautiful painting that has been damaged, it is said. The ossuary is valuable because it is a historical relic. As such, it is priceless and worth just as much with the cracks as it was in Golan’s apartment. An extended lawsuit may be required to settle these questions.

Ethical questions also arise. Two academic associations—the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) and the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR)—have 024policies urging their members to ignore any artifact that surfaces via the antiquities market. Such artifacts are unprovenanced; that is, we don’t know where they came from. They have no context. No article may be published in the professional journals of these societies concerning an unprovenanced artifact. No paper may be presented at their meetings concerning an unprovenanced artifact. And members are encouraged to ignore any exhibit of such an artifact. ASOR’s policy statement on the subject provides that “ASOR members should refrain from activities that enhance the commercial value of [unprovenanced] artifacts, for example, publication, authentication, or exhibition. ASOR publications and its annual meeting will not be used for presentations of such illicit material.”

The Society of Biblical Literature (SBL), in contrast, held a special session on the James ossuary at its annual meeting in Toronto, featuring scholars from France, Australia, Canada and the United States (we will give a full report on that session in our next issue). ASOR met in Toronto just before SBL, but took no official notice of the ossuary, although many of its members took a peek at it in the museum.

BAS’s position on looting and the antiquities market is quite different. We, too, despise looters and abhor the damage they do. We quite agree that much is lost when an object has no context. But not everything is lost. Unlike ASOR and AIA, we believe in a variety of market-based strategies to reduce, if not eliminate, looting, rather than simply vilifying collectors, antiquities dealers and museums that display such artifacts in the vain hope that this will eliminate the antiquities market. Market-based solutions that we favor include selling some of the thousands of duplicates of such low-value items as pots and oil lamps, thus putting some looters out of business. Who would buy an illicitly excavated pot (which might be a forgery) when he or she could buy a government-authenticated pot with a legal permit to export it? Another strategy would be to employ local peasants under the supervision and direction of professional archaeologists to excavate sites that are being looted when the looting cannot be otherwise prevented. In short, the looting problem is really a variety of problems that require a variety of strategies to address them. These strategies should at least be explored.

The strategies of the AIA and ASOR haven’t worked. Looting is worse than ever. The effect of the policies of these organizations has been only to drive the market underground so that we don’t even hear about some extremely important artifacts.

We also believe that it is absurd to ignore important artifacts—like the James ossuary—simply because they came to public attention via the antiquities market. It is far better to encourage collectors to allow scholars to study and publish their significant artifacts and to allow their treasures to be exhibited in museums so that the public can share in them than to pretend that these artifacts don’t exist. Frankly, we cannot understand anyone who would argue that we should ignore the Dead Sea Scrolls because most of them were looted or that we should avert our eyes to avoid acknowledging the existence of the James ossuary.

025

In some cases, there will be arguments about whether an item is a fake or not (although there is not much question about the authenticity of the James ossuary inscription). The question of forgery should indeed be part of the discussion. In the same way, there will be arguments about artifacts that are professionally excavated—their date, what they are and what their significance is. In archaeology uncertainty is often part of the game, regardless of whether an object is unprovenanced or excavated professionally.

The position taken by ASOR and AIA also makes it difficult on some of their colleagues who are leading scholars. You cannot be a paleographer and ignore the market. All great paleographers—André Lemaire of the Sorbonne, Frank Cross of Harvard, the late Nahman Avigad of Hebrew University, Kyle McCarter of Johns Hopkins University, Dennis Pardee of the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute—deal with and publish unprovenanced inscriptions. You cannot be a numismatist if you ignore the antiquities market. Probably more than 90 percent of ancient coins come to scholarly attention via the antiquities market; this was true even before the ubiquity of the metal detector. In many cases, you cannot even be an historian if you ignore the antiquities market. The moral posturing of ASOR and the AIA unfairly leaves an ethical taint on some of their most illustrious colleagues. And younger scholars are fearful of dealing with unprovenanced objects, lest some colleague in ASOR or AIA blackball them for tenure at the institutions where they teach.

The James ossuary is likely to open a public discussion of these important issues beyond the pages of BAR and its sister magazine, Archaeology Odyssey. A recent article in the National Review (“In a Box,” November 25, 2002) observed that “there’s no easy way to suppress [the antiquities market]—and the hope that it might be eliminated is not realistic. The notion that a scholarly boycott can have an impact is sheer fantasy.” The article suggests a number of strategies similar to ours.

Finally, from the halls of academe to the internet, an enormous amount of scholarly discussion is taking place regarding the James ossuary inscription and its implications. The Institute for Advanced Study of Hebrew University devoted a session to it and one participant wrote us: “Nobody at all cast doubt on the authenticity of the ossuary and of the inscription written on it. Ada Yardeni [who drew the inscription for BAR] was there and no one challenged at all her assertion that the writing is authentic.”

On the other hand, the doubters are also coming out of the woodwork. One marginalized scholar (his own word) with little, if any, experience as a Hebrew/Aramaic paleographer has attacked the authenticity of the inscription saying that it is “just too pat,” without further specification. Another scholar claims that the last part of the inscription (“brother of Jesus”) is in a different hand from the first part of the inscription. This is a legitimate question, but that is as far as the scholars we have talked to are willing to go. They continue to believe that there is only one hand in the inscription, despite the fact that some letters in the second part are more difficult to read and are in cursive or semi-cursive, rather than in formal script. In any event, it is unclear what it would mean if two hands did engrave the inscription. One person suggested that a forger in about 300 A.D. added “Brother of Jesus” to the inscription. But this seems a bit far-fetched. The person who is most certain and vociferous in claiming that different hands were responsible for the first and second parts of the inscription is also certain that the inscription is excised, rather than incised; that is, the space around the letters has been carved out leaving the letters protruding in relief. It is difficult to understand how she could have been so certain when she had never seen the ossuary itself. The experts who have seen the ossuary and studied the inscription continue to maintain that the inscription is plainly engraved—incised, not excised.

Mainstream scholars, on the other hand, are also debating the theological implications of the inscription—assuming it is authentic and that it refers to the three New Testament personages. What does it suggest about the relationship between James and Jesus (full brother, half brother, step-brother, kin, cousin)? What does it imply about the virginity of Mary, either her perpetual virginity or her virginity at the time Jesus was born?

At this point the story is still growing. More to come.

News of our exclusive cover story in the last issue about the bone box inscribed “James, the son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” has reverberated around the globe. The day after we released the issue of BAR, the bone box, or ossuary, was featured in color on the front page of the New York Times. Articles about the ossuary appeared on the front page of the Washington Post, the International Herald Tribune (with a picture of BAR’s cover) and almost every other newspaper in the world. The Jerusalem Post ran an extensive question-and-answer interview with the editor of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username