049

A few years ago the archaeological world, not to mention the popular press, was abuzz with news that an early Christian church had been discovered on the grounds of an Israeli prison at Megiddo. As BAR reported in an article by archaeologist Vassilios Tzaferis, the structure featured mosaics with Christian symbols such as fish and, most exciting, a dedicatory inscription “to God Jesus Christ.”a Excavator Yotam Tepper of the Israel Antiquities Authority and Hebrew University paleographer Leah Di Segni dated the building to around 230 A.D., making it one of the earliest, if not the earliest, known churches and inscriptional references to Jesus. Even more recent excavations in Israel, Turkey and Egypt have produced amazing new church discoveries that are illuminating the early Christian communities at important sites, including Laodicea, one of the seven churches of Revelation, and Horvat Midras, which may be the hometown of the prophet Zechariah.

050

Earlier Christian gathering places—from before the fourth century—are more difficult to identify because at that time Christians met together mostly in private homes to pray, sing, share the Eucharist, and discuss matters of importance to the community. The Greek word for church—ekklesia, which means “assembly” or “congregation”—referred simply to groups of Christians in the same community or as a whole. Eventually, however, the word came to mean also the buildings in which Christians gathered to worship. Even as Christian populations grew, distrust and persecution by their Roman rulers forced the early church to stay out of the public eye. Indeed, even the impressive prayer hall found at the Megiddo prison appears to have been built as part of a larger residential and administrative building for Christian members of the Roman military.

The situation changed in 313 when the emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, making Christianity a licit religion of the Roman Empire. With this acceptance came the construction of large public buildings, or churches, to serve the worship needs of Christians throughout the empire.

In early February 2011 the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) announced that its archaeologists had uncovered a large Byzantine Church at Horvat Midras about 15 miles southwest of Jerusalem. But this was no simple story of archaeological digging and discovery.

051

Scholars had known about archaeological remains at the site since at least the 19th century. In the 1980s a decorated lintel was found there that was almost an exact duplicate of one found in an ancient synagogue. On this basis, archaeologists Amos Kloner and Zvi Ilan theorized that an ancient synagogue might be buried there. The spot remained untouched for decades, however.

Only in 2010, following an attempted antiquities robbery by looters at the site, did the IAA begin an official excavation of the monumental building to which the lintel belonged. The project was directed by Amir Ganor and Alon Klein of the IAA’s Unit for the Prevention of Antiquities Robbery.

The excavations revealed a sizable Jewish settlement dating from the Second Temple period to the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (132–135 A.D.). During that time a large public compound was built here, as well as a sprawling subterranean complex that included rooms, water installations, and storerooms that likely served as rebel hiding places during the two Jewish revolts against Rome in 66–70 and 132–135 A.D. Coins, stone vessels, lamps and other pottery confirm the dates and Jewish character of the underground passageways.

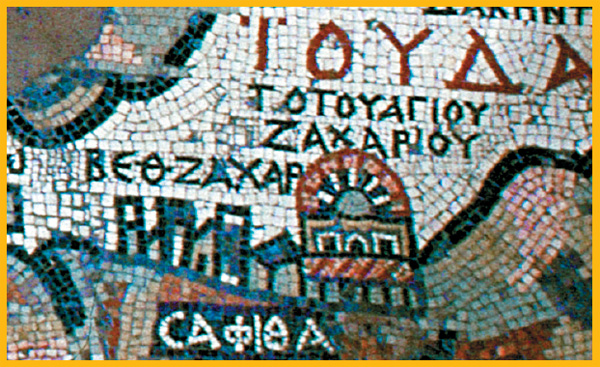

The Byzantine structure, which was used as a church in the fifth–seventh centuries, is located inside the earlier Jewish compound. It is a basilica with a large flagstone courtyard leading to the main entrance. The nave, which featured eight marble columns with capitals specially imported from Turkey, was flanked by a wide aisle on either side and ended in a raised bema with a semicircular apse. Behind the bema are two rooms, one of which led to a vacant tomb. Some experts believe this may be the site early Christians identified as the burial place of the sixth-century B.C. prophet 052 053 Zechariah.1 The famous sixth-century A.D. Madaba map refers to a village called Bethzachar (“the house of Zechariah”) and a structure there called the “Sanctuary of Zechariah.” Byzantine travelers’ descriptions and the approximate location of the site on the map fit with that of the Horvat Midras church. This church therefore may have been built to mark Zechariah’s tomb, but more study is needed to confirm the theory.

The highlight of the basilica is the mosaic carpeting. The colorful geometric patterns and images of fish, peacocks, lions and foxes are rare in both the level of craftsmanship and the state of preservation when they were unearthed, according to excavator Ganor. The exquisite mosaics underwent preliminary preservation treatment, after which the IAA planned to cover them to protect them until the site could be more fully conserved and prepared for the public.

But the story doesn’t end there.

Rather than re-covering the mosaics, the IAA decided to keep them open for a while longer to accommodate the flow of visitors coming to see the extraordinary artwork.

Then disaster struck. On the morning of March 24, 2011, project director Alon Klein arrived at the site to discover that someone had attacked the mosaic with a hammer. Klein described it as “heart-breaking … The mosaic looks like it has been hit by mortar shelling.” In the wake of the vandalism, the IAA finally covered the mosaics, stating that they hoped the mosaics could be mostly preserved, although it will now require significantly more time and money.

Given the importance of Asia Minor to the apostle Paul and other early followers of Jesus, it should come as no surprise that a church from the fourth century was discovered recently in western Turkey. Turkey announced at the end of January 2011 that a large, well-preserved church had been found at Laodicea using ground-penetrating radar. According to excavation director Celal Şimşek of Pamukkale University, the church was built during the reign of Constantine (306–337) and destroyed by an earthquake in the early seventh century. There are 11 apses—one facing east and five each on the northern and southern sides. Floral and geometric mosaics as well as opus sectile pavement cover the floors. The cross-shaped marble baptistery, located at the end of a long corridor on the north side of the church, is one of the oldest and best-preserved ever discovered.

Laodicea is mentioned several times in the New Testament, in both Paul’s letter to the Colossians (2:1, 4:13–16) and the Book of Revelation, in which it is one of the seven churches in Asia [Minor] to receive the message revealed to John that the “time is near” (Revelation 1:3, 11, 3:14–22). Paul’s letter suggests that Laodicea had a very early Christian community with close ties to the one in Colossus (11 mi away), possibly having been evangelized by Paul’s disciple Epaphras, who is mentioned by name in the epistle.

In the Book of Revelation, however, the Laodiceans are chastised for being “lukewarm, neither cold nor hot” and for failing to recognize their spiritual want in the midst of their material wealth and prosperity (Revelation 3:16–17). The ruins of ancient Laodicea indicate that its residents were indeed fairly well-to-do, no doubt benefiting from their position on a bustling trade route.b According to first-century Greek historian Strabo, Laodicea was also home to a well-known medical school.2 The Seleucid king Antiochus II of Syria founded Laodicea ad Lyceum (as it is more properly called) between 261 and 253 B.C. and named it in honor of his wife, Laodice. Remains 054 from the Hellenistic and Roman periods include two theaters, a stadium and a nymphaeum, a monumental fountain that continued in use into the Byzantine period (fourth–seventh centuries), when it was walled off and converted into a Christian structure.

A bishop’s seat was located at Laodicea very early on, and it remains a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church today, although the city is uninhabited and the bishop’s seat has been vacant since 1968. In 363–364 A.D., clergy from all over Asia Minor convened at the regional Council of Laodicea to discuss issues of clerical and lay conduct and to specify the authoritative texts of the Biblical canon. The council included the Book of Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah in its canon of the Old Testament but did not include the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. (The later ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 and the Quinisext Council of 692 confirmed all the decisions of the Laodicean Council, although the Biblical canon differs somewhat today.c) It is possible that the newly discovered church is the very same building where Asia Minor’s clergy met to hold the influential Council of Laodicea, but certainly much remains to be revealed and studied here.

The Monastery of St. Apollo in Bawit, Egypt (located south of Amarna near the Nile), was founded in the late fourth century by the Coptic Christian monk Apollo. In the early 20th century, French excavations exposed much of the monastery complex including two churches. Many of the finds were transported to the Louvre in Paris, where they are now on display.

In April 2010, a third church was discovered at the monastery, using geomagnetic equipment. Near the church was a hermitage and a vaulted room with paintings. Although the architectural details of the church are still unclear, archaeologists say that the large structure dates before the Islamic conquest of 641 A.D. and is more than double the size of one of the previously unearthed churches.

Beneath the floor of the church were several burials. The excavators believe they are most likely monks from the monastery, but the archaeologists had to stop digging until the human remains could be analyzed by an expert. Some have wondered if the burials might include the remains of St. Apollo himself, but only further excavation can reveal inscriptional evidence that might make such an identification possible.

Then in May 2010, Egyptian archaeologists working on the Avenue of Sphinxes project, which restored the recently reopened ancient 1.7-mile processional way that connects the great temples of Luxor and Karnak, announced that they had excavated another fifth-century Coptic Church, as well as a nilometer (a stepped structure used to measure the level of the Nile during floods).

According to director Zahi Hawass in a statement released by Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, the 1,600-year-old church was built using recycled limestone blocks from ancient Egyptian temples that once stood along the avenue. Some of the stones of the church bear depictions of Ptolemaic and Roman kings offering sacrifices to the Egyptian gods.

Since the political and archaeological upheaval of early 2011, the continued excavation and study of these two great churches in Egypt are uncertain. Not only was there a danger of looting,d but Coptic Christians, who constitute about 10 percent of Egypt’s population, have come under increased attacks this year. Targeted by extremist Islamist factions, Coptic churches have been the scene of murder, mayhem and destruction by explosives and fire.

As Copts live in a state of fear in Egypt, the ancient history of their churches waits to be fully revealed.

A few years ago the archaeological world, not to mention the popular press, was abuzz with news that an early Christian church had been discovered on the grounds of an Israeli prison at Megiddo. As BAR reported in an article by archaeologist Vassilios Tzaferis, the structure featured mosaics with Christian symbols such as fish and, most exciting, a dedicatory inscription “to God Jesus Christ.”a Excavator Yotam Tepper of the Israel Antiquities Authority and Hebrew University paleographer Leah Di Segni dated the building to around 230 A.D., making it one of the earliest, if not the earliest, known churches and […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Vassilios Tzaferis, “Inscribed ‘To God Jesus Christ,’” BAR 33:02.

See Katharine Eugenia Jones, “Expeditions,” BAR 25:01.

For more on the development of the Biblical canon, see Roy W. Hoover, “How the Books of the New Testament Were Chosen,” Bible Review 09:02.

See “Revolts, Robbers and Rumors,” sidebar to “Egypt’s Chief Archaeologist Defends His Rights (and Wrongs),” BAR 37:03.