The Persian emperor Cyrus is honored as the only foreigner in the Bible to be identified as the “messiah” or “anointed one” of YHWH, the Israelite God.1 Isaiah tells us that YHWH spoke “to his messiah, to Cyrus, whom I [YHWH] took by his right hand to subdue nations before him” (Isaiah 45:1).

The title messiah means “anointed.” It is an anglicization of the Hebrew meshiach (

Many people are anointed in the Hebrew Bible, and many are referred to as the “messiah” or “anointed one.” The high priest is called the “anointed priest” (Leviticus 4:3, 5, 16, 6:15). God tells Elijah to anoint two different men as kings of their people: Hazael as king of Aram (1 Kings 19:15) and Jehu son of Nimshi as king over Israel. God also instructs Elijah to anoint his own successor, Elisha son of Shaphat, as prophet (1 Kings 19:16). At this point in time, the term “messiah” or “anointed one” did not refer to the apocalyptic savior of humankind.

These people are called “messiah” or “anointed one,” but they aren’t designated “YHWH’s messiah,” as Cyrus is. This much less common phrase (including variants such as “my anointed” or “his anointed”—always referring to YHWH, the God of Israel) appears only 30 times in the Hebrew Bible, and always in reference to the legitimate anointed king of Judah. It is applied to Saul eleven times (1 Samuel 12:3, 5, 24:6 [twice],10, 26:9, 11, 16, 23; 2 Samuel 1:14, 16); to David three times (1 Samuel 16:13; 2 Samuel 19:22, 23:1); and to an unnamed king of either the United Monarchy or Judah (1 Samuel 2:35). It also refers to the Judahite king in Lamentations (4:20); in eight psalms (Psalms 2:2, 18:50, 20:6, 28:8, 45:7, 84:9, 89:20, 38, 51, 132:10, 17); in Habakkuk’s prayer (3:13); and in the prayer of Hannah (1 Samuel 2:10). But in Isaiah 45:1 the phrase refers to Cyrus, a Persian monarch.

The non-Jew Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 B.C.E.), whom Isaiah 45 calls YHWH’s anointed, was the Persian king of Fars, a southern province of present-day Iran. The Greek historians and the chronicle of the last Babylonian king Nabonidus tell us that in 553 B.C.E. Cyrus rebelled against the ruling Medes, then a major power in the Near East. By 550 he had defeated them and imprisoned their king, his maternal grandfather, Astyages.2 He then turned to the west. By 546 he had defeated the wealthy king Croesus of Lydia (in modern Turkey), and the Lydian capital of Sardis fell to him along with all the other cities of Asia Minor. Cyrus then turned his attention to the most powerful kingdom in Central Asia: Babylon. By the end of 539, he had taken Babylon and captured its king, Nabonidus.3 The Persian empire founded by Cyrus extended from the Aegean to Central Asia.

It was probably in the fall of 538 that Cyrus issued a decree permitting the Jews of the Babylonian Exile to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their Temple. According to the Book of Ezra, Cyrus told the Jews:

Thus said King Cyrus of Persia: YHWH God of Heaven has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and has charged me with building Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Anyone of you of all His people—may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem that is in Judah and build the House of YHWH God of Israel, the God that is in Jerusalem; and all who stay behind, wherever he may be living, let the people of his place assist him with silver, gold, goods, and livestock besides the freewill offering to the House of God that is in Jerusalem.a

(Ezra 1:2–4; see also Ezra 1:1–11)4

According to Ezra, Cyrus also refurbished the Temple:

But in the first year of King Cyrus of Babylon, King Cyrus issued an order to rebuild this House of God. Also the silver and gold vessels of the House of God that Nebuchadnezzar had taken away from the Temple in Jerusalem and brought to the temple in Babylon—King Cyrus released them from the temple in Babylon to be given to the one called Sheshbazzar whom he had appointed governor. He said to him, “Take these vessels, go, deposit them in the Temple in Jerusalem, and let the House of God be rebuilt on its original site.”

(Ezra 5:13–15; cf. 6:1–5)

Isaiah also mentions Cyrus in connection with rebuilding the Temple:

Thus said YHWH, your Redeemer, who formed you in the womb: “It is I, YHWH, who made everything, who alone stretched out the heavens and unaided spread out the earth” … The same who says of Cyrus, “He is my shepherd, he shall fulfill all my purposes!; He shall say of Jerusalem, ‘She shall be built,’ and to the Temple, ‘Your foundation shall be found again.’”

(Isaiah 44:24, 28)

Who is this prophet who identifies Cyrus as YHWH’s “shepherd” and “anointed”?

We must be careful at this point to distinguish between two Isaiahs, both in the same book of the Bible. Scholars label them as First Isaiah and Second Isaiah. First Isaiah, who is credited with writing much of Isaiah 1–39, lived in Jerusalem during the reigns of Ahaz and Hezekiah (Isaiah 1:1, 6–8, 36–39). Second Isaiah, author of Isaiah 40–65, probably lived in Babylon during the late Exilic period (late sixth century B.C.E.). We know he wrote after 539 because Isaiah 40–65 mentions Cyrus the Great (see “Who Wrote Second Isaiah?”).

Second Isaiah believed the Jews had completed their punishment for whatever sins they had committed, and he encouraged those exiled in Babylon and Egypt to return home to Judah:5

Comfort, O comfort My people,

Says your God.

Speak tenderly to Jerusalem,

And declare to her

That her term of service is over,

That her iniquity is expiated;

For she has received at the hand of YHWH

Double for all her sins.(Isaiah 40:1–2)

And now YHWH has resolved—

He who formed me in the womb to be His servant—

To bring back Jacob to Himself,

That Israel may be restored to Him.

And I have been honored in YHWH’s sight,

My God has been my strength …

I will make all My mountains a road,

And My highways shall be built up.

Look! These are coming from afar,

These from the north and the west,

And these from the land of Sinim [modern Aswan].

Shout, O heavens, and rejoice, O earth!

Break into shouting, O hills!

For YHWH has comforted his people;

And has taken back his afflicted ones in love.(Isaiah 49:5, 11–13)

What does it mean to be called “YHWH’s anointed,” as Cyrus is called by Second Isaiah? As we have seen, the title always refers to the ruler of Judah. To the biblical writers, however, the term “YHWH’s anointed” is more than a title. It also connotes a theology. “YHWH’s anointed” is the legitimate king appointed and protected by God. In the Psalms, he is idealized, mythical. According to Psalm 2, which has long been recognized as a poem recited at the coronation of a Judahite king, the king is anointed by YHWH during the installation process:

[YHWH says,] “But I have installed6 my king

on Zion, My holy mountain!”7

Let me tell of the decree:

YHWH said to me,

“You are my son,

I have fathered you this day.

Ask of Me,

and I will make the nations your domain;

your estate, the limits of the earth.

You can smash them with an iron mace,

shatter them like potter’s ware.”(Psalm 2:6–9)

YHWH has given to his anointed king all the nations of the earth as his inheritance. This theme of sovereignty over the nations is echoed in Psalm 18. Here, the anointed one is the reigning Davidic king:

YHWH lives! Blessed is my rock!

Exalted be God, my deliverer,

the God who has vindicated me

and made peoples subject8 to me,

…

He accords great victories to His king,

keeps faith with His anointed,

with David and his offspring forever.(Psalm 18:47–48, 51)

As in Psalm 2, this psalm describes YHWH giving the anointed victory and placing him at the head of nations. Similarly, Psalm 20 stipulates that it is not chariots or horses that bring the anointed one victory, but reliance on YHWH:

May we shout for joy in your victory,

arrayed by standards in the name of our God.

May YHWH fulfill your every wish.

Now I know that YHWH will give victory

to His anointed,

will answer him from His heavenly sanctuary

with the mighty victories of His right arm.

They [call] on chariots, they [call] on horses,

but we call upon the name of YHWH our God.

They collapse and lie fallen,

but we rally and gather strength.

O YHWH, grant victory!

May the King answer us when we call.(Psalm 20:6–10)

How then, knowing the full theology associated with the term “YHWH’s anointed,” could Second Isaiah have applied this title to Cyrus, the Persian emperor?

Whenever Cyrus (r. 550–530 B.C.E.), or his son and successor Cambyses (r. 530–522 B.C.E.) or Cambyses’s successor Darius (r. 522–486 B.C.E.) extended the mighty Persian empire, local priests of powerful temples would apply the titles and theologies of their own kings to their Persian conquerors. Second Isaiah appears to have done the same.

After Cambyses successfully invaded Egypt, the local priests hailed him as pharaoh, or “King of Upper and Lower Egypt.”

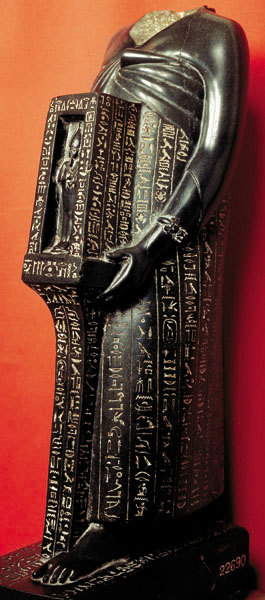

In an autobiographical inscription (photo, above), the priest

The Great Chief of all foreign lands, Cambyses, came to Egypt, and the foreign peoples of every foreign land were with him. When he had conquered this land in its entirety, they established themselves in it, and he was Great Ruler of Egypt and Great Chief of all foreign lands. His Majesty assigned to me the office of chief physician. He made me live at his side as companion and administrator of the palace. I composed his official pharaonic title, to wit his name of King [Pharaoh] of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mesuti-Re (Offspring of Re).9

Another priestly Egyptian inscription identifies Cambyses with a typical combination of pharaonic titles: “The Horus Who Unites the Two Lands, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Son of Re, The Good God, Lord of the Two Lands.”10 This Egyptian sarcophagus shows Cambyses in pharaonic dress kneeling beside an offering table. The accompanying inscription notes that Cambyses is performing the appropriate rites to conduct his “father,” the Apis bull—identified with Osiris, the god of the underworld—to the good land of the West.11

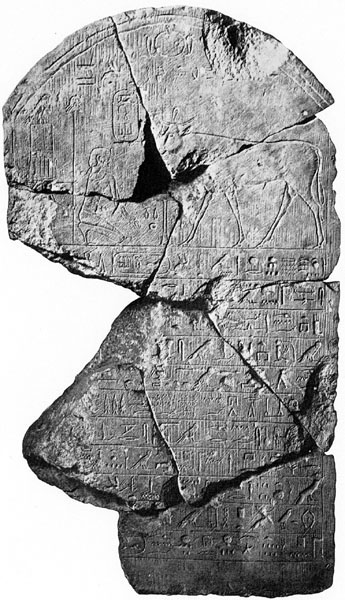

After Darius rose to power, he cut a canal (an early Suez Canal) to connect the Red Sea to the Nile River. The commemorative stelae erected along the route identified12 him as one “born of Neith” (Re’s mother) and as “he whom [Re] placed on his (Re’s) throne in order to achieve what he (Re) had begun.”

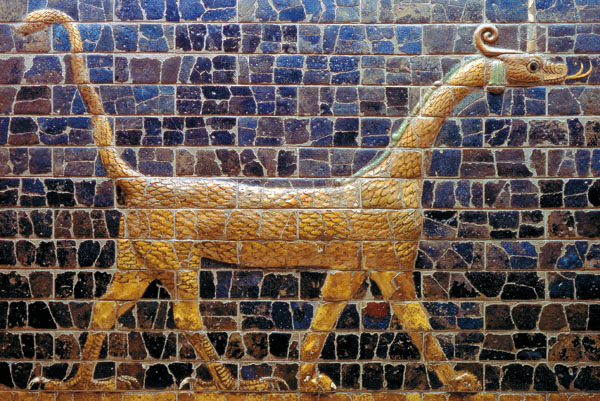

In Babylon, too, Cambyses was hailed as the Babylonian crown prince and, later, as king. The Babylonian Chronicle indicates that during the reign of Cyrus, his son Cambyses assumed the role of the crown prince in the New Year’s Akitu festival, a ceremony reserved for the legitimate Babylonian monarch.13 During the ceremony, Cambyses went to the temple of the god Nabu and prepared to lead him to the sanctuary, called Esagil, of their chief god Marduk. Cambyses was immediately named king of Babylon; several texts from this period are dated to “the first year of Cyrus, king of lands, and Cambyses, king of Babylon.”14

Why did the priests of Marduk allow Cyrus to participate as crown prince in the Akitu festival? Why did the Egyptian priests identify Cambyses and Darius as pharaoh?

First, self-interest. These priests tied their own successes to the success of their conquerors.15 The Egyptian priest

Second, the priests recognized that the restoration of their temples depended on the good will of the Persian leader.

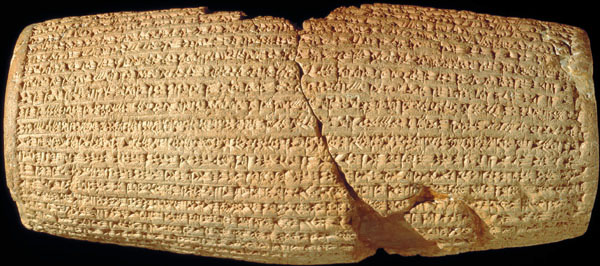

The famous Cyrus Cylinder, a 10-inch-long inscribed clay barrel bearing the story of Babylon’s “liberation” by Cyrus, tells how Cyrus, with the help of the Babylonian god Marduk, restored worship at temples where Nabonidus had removed the cult images and brought them to Babylon.

From [Babylon] up to the city of Ashur and Susa, Akkad, to the land of Eshnunna, to the towns Zamban, Me-Turnu, Der up to the region of the Gutians, I returned to (these) sacred cult-cities on the other side of the Tigris, the sanctuaries of which have been ruins for a long time, the gods who live in them and established for them eternal sanctuaries. I (also) gathered all their inhabitants and returned them to their habitations. Furthermore, I resettled upon the command of Marduk, the great Lord, all the gods of Sumer and Akkad whom Nabonidus has brought into Babylon to the anger of the Lord of the gods, unharmed, in their chapels, the places which make them happy.16

More importantly for the Marduk priesthood located in the city of Babylon, Cyrus removed the stigma of corvée labor:

As to the inhabitants of Babylon, whom he [Nabonidus] against the will [of the gods] made them pull the yoke—which for them was not appropriate—for their exhaustion I provided rest. I removed the yoke.17

Similarly, a generation later,

His majesty [Cambyses] commanded to expel all the foreigners [who] dwelt in the temple of Neith, to demolish all their houses and all their unclean things that were in this temple.

When they had carried [all their] personal [belongings] outside the wall of the temple, his majesty commanded to cleanse the temple of Neith and to return all its personnel to it […] and the hour-priests of the temple. His majesty commanded to give divine offerings to Neith-the-Great, the mother of god, and to the great gods of Sais, as it had been before. His majesty commanded [to perform] all their festivals and all their processions, as had been done before. His majesty did this because I had let his majesty know the greatness of Sais, that it is the city of all the gods, who dwell there on their seats forever.

But

As the British historian Alan Lloyd has noted,

The king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Cambyses, came to Sais. His majesty went in person to the temple of Neith. He made a great prostration before her majesty, as every king has done. He made a great offering of every good thing to Neith-the-Great, the mother of god, and to the great gods who are in Sais, as every beneficent king has done. His majesty did this because I had let his majesty know the greatness of her majesty Neith, that she is the mother of Re himself.18

Cambyses’s willingness and capacity to adopt the Egyptian model of kingship seems crucial to

Similarly, in Babylon, when Cyrus returned the cult statues that had been removed under the last Babylonian king, Nabonidus, and restored the sanctuaries, the local priests could interpret this as a sign of their god’s joy at Cyrus’s rule. The Marduk priests, like

Indeed, throughout the Near East, conquered peoples interpreted their fate similarly: When a town was conquered or destroyed, the devastation was attributed to the god’s displeasure in the citizens. The restoration of order—particularly the restoration of the city to its former glory and the presence of the god’s statue back in his sanctuary—was seen as proof that the local god had participated in the conquest, had negotiated his own return and had restored order.

Might Second Isaiah have been motivated by the same reasons: self-interest, desire to restore the Temple, belief that the Judeans had been conquered because they had been untrue to their God, belief that their term of service was now over, and belief that Cyrus was able to restore the Temple because YHWH favored him and his work on behalf of the Jews?

Like

Just as

With the name went the entire royal Judean court theology associated with it. Second Isaiah applies to Cyrus the same themes associated with YHWH’s anointed in the Psalms: victory over the enemy, nations falling under his feet. In Isaiah 41 and 45, we read of YHWH’s selection of Cyrus as the victor who will subdue nations:

Who has roused a victor

from the East [Cyrus],b

Summoned him to His service?

Has delivered up nations to him,

And trodden sovereigns down?

Has rendered their swords like dust,

Their bows like windblown straw?

He pursues them, he goes

on unscathed;

No shackle is placed on his feet.

Who has wrought and achieved this?

He who announced the generations from the start—

I, YHWH, who was first

And will be with the last as well.

… I have roused him from the north,

and he has come,

From the sunrise, one who invokes

My name;20

And he has trampled rulers like mud,

Like a potter treading clay.

Who foretold this from the start,

that we may note it;

From aforetime, that we might say,

“He is right”

Not one foretold, not one announced;

No one has heard your utterance!(Isaiah 41:2–4, 25–26a)

Thus said YHWH to Cyrus,

His anointed one

Whose right hand He has grasped

Treading down nations before him

Uncovering the loins of kings

Opening doors before him

and letting no gate stay shut:

I will march before you

and level the hills that loom up;

I will shatter doors of bronze

and cut down iron bars.

The very imagery used to describe YHWH’s assistance to the Davidic monarch is now applied to Cyrus. In Second Isaiah, YHWH subdues kings for Cyrus (Isaiah 41:2; cf. Psalm 18:48). He causes Cyrus to trample on rulers like mortar, like the potter treads the clay (Isaiah 41:25; cf. Psalm 2:9).

In Second Isaiah, YHWH makes it clear that it is now Cyrus, and not the Davidic monarch, who will fulfill YHWH’s purposes. The above passage (Isaiah 45:1, 2) concludes as follows:

It was I who roused him [Cyrus]

for victory,

And who level all roads for him.

He shall rebuild My city,

And let my exiled people go

Without price and without payment,

—said YHWH of Hosts.(Isaiah 45:13)

Like

This article is based on Lisbeth S. Fried, “Cyrus the Messiah? The Historical Background to Isaiah 45:1, ” Harvard Theological Review 95:4 (2002), pp. 373–393.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Here and throughout the article, the translation is based on the New Jewish Publication Society version.

Traditional exegetes have taken this passage to refer to Abraham and his encounter with the several kings described in Genesis 14. References to Cyrus by name in the second half of the book of Isaiah have led modern scholars to conclude that this is a description of Cyrus’s activities against the Medes, the Lydians and finally the Babylonians—the great powers of the day. In the passage here, Cyrus is not mentioned by name, but the description of him is the same as in Isaiah 45:1–13, where his name is explicitly stated.

Endnotes

YHWH is the Hebrew name of the God of Israel, the God of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, transcribed into English letters. (The Hebrew letters are yud [Y], heh [H], wow [W], and heh [H].) They spell God’s personal name. Since the Hebrew text uses consonants only—no vowels—scholars are not certain how the name is to be pronounced. The first translation of the Hebrew Bible (which was from Hebrew into Greek) did not employ God’s name, but substituted instead kyrios, “Lord,” everywhere that the name occurs. This custom was followed by nearly every other translation of the Bible, so that in most English versions we have “The Lord” instead of his name. In German we have Der Herr. When translating the biblical texts, I prefer to use God’s name as the biblical writers did.

Diodorus Siculus 9.22; The Nabonidus Chronicle 2.1–4; the Babylonian Chronicle 3.14–15; Herodotus I:123–130.

For a recent history, see Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter Daniels (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), pp. 13–44.

The authenticity of this decree is disputed. For my view regarding its historicity, see Lisbeth S. Fried, “The Land Lay Desolate: Conquest and Restoration in the Ancient Near East,” in Oded Lipschits and Joseph Blenkinsopp, Judah and Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003); and Lisbeth S. Fried, The Priest and the Great King: Temple-Palace Relations in the Persian Empire (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns [forthcoming]). For its date in the fall of 538, see Fried and David Noel Freedman, “Was There a Jubilee Year in Pre-Exilic Judah?” excursus in Jacob Milgrom, Leviticus 23–27, Anchor Bible series (New York: Doubleday, 2001), pp. 2257–2270.

I discuss the date of this Second Isaiah in Fried, “Cyrus the Messiah? The Historical Background to Isaiah 45:1, ” Harvard Theological Review 95:4 (2002), pp. 373–393.

Repointing nesukoti, from suk, to anoint, with Mitchell Dahood, Psalms I (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), p. 10.

His king … his holy mountain. For a discussion of -y as the third pronominal suffix, see Dahood, Psalms I, p. 10.

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. 3, The Late Period (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1980), pp. 36–41, esp. n.9, p. 40.

Georges Posener, La première domination perse en Êgypte (Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1936), p. 31.

Posener, La première domination, nos. 8–10, pp. 48–87, pl. IV-XV. Diodorus claimed Darius did not finish the canal (I.33.9); however, a second stela found 3 kilometers south of Kabret states “ships filled with … arrived in Persia” indicating the canal was completed (line 16; Posener, p. 76). The location of a fourth stela is unknown. See Posener, p. 48, n.3; and C. Tuplin, “Darius’ Suez Canal and Persian Imperialism,” Achaemenid History VI (1991), pp. 237–283.

Pace A. Kuhrt and S. Sherwin-White (“Xerxes’ Destruction of Babylonian Temples,” Achaemenid History II: The Greek Sources [Leiden, 1987], pp. 79–80) who argue there is no evidence that any Persian king ever participated in the Akitu festival. See my Harvard Theological Review article for a discussion.

Stefan Zawadzki, “Cyrus-Cambyses Co-regency,” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 90 (1996), pp. 171–183.

Alan B. Lloyd, “The Inscription of

Hanspeter Schaudig, “Die Inschriften Nabonids von Babylon und Kyros des Grossen samt den in ihrem Umfeld entstandenen Tendenzschriften: Textausgabe und Grammatik,” Alter Orient und Altes Testament 256 (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2001), pp. 550–556; “Cyrus Cylinder,” in The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 316.

Vocalized with the Greek to the niphal, “He is called by my name.” However, if the prophet is describing Cyrus as calling upon YHWH by name, it would not be a problem. The Egyptians described Cambyses and Darius as calling upon the Egyptian gods and the priests of Marduk described Cyrus as calling upon the Babylonian god. These poems do not present Cyrus as he really was, but as at least one Judahite wanted him to be.

The argument presented here does not depend on the accuracy of the Isaianic writer, only that he believed that Cyrus would restore the status quo ante. But see Fried, “‘The Land Lay Desolate’: Conquest and Restoration in the Ancient Near East,” in which I argue that the Temple was indeed rebuilt, the vessels restored, and the people returned under Cyrus. For a full discussion of all the issues, see Ephraim Stern, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, vol. 2, The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Periods (732–332), Anchor Bible Reference Library (New York: Doubleday, 2001), pp. 312–326; Stern, “The Babylonian Gap,” BAR 26:06; Charles E. Carter, The Emergence of Yehud in the Persian Period: A Social and Demographic Study, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supp. Series 294 (Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999), p. 225; David Stephen Vanderhooft, The Neo-Babylonian Empire (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1999); and most recently Lipschits and Blenkinsopp, Judah and Judaeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period.