Debunking the Shroud: Made by Human Hands

027

When the Shroud of Turin went on display this spring for the first time in 20 years, it made the cover of Time magazine with the blurb “Is this Jesus?” In BAR, we summarized the controversy that has enshrouded this relic, venerated for centuries as the burial cloth of Jesus (“Remains to Be Seen,” Strata, BAR 24:04).

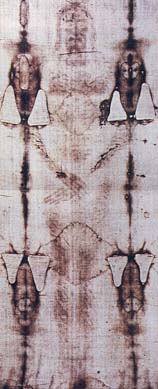

Following Time’s lead, we reported that although radiocarbon tests have dated the shroud to 1260–1390 A.D., no one has been able to account for the shadowy image of a naked, 6-foot-tall man that appears on the shroud. With bloodstains on the back, wrists, feet, side and head, the image appears to be that of a crucified man. The details—the direction of the flow of blood from the wounds, the placement of the nails through the wrists rather than the palms—display a knowledge of crucifixion that seems too accurate to have been that of a medieval artist.

But two of BAR’s savvy readers have objected to our assessment. The following articles suggest there is no reason to doubt that the image, as well as the cloth, was produced in the Middle Ages.—Ed.

Nothing puzzles and intrigues the sindonologist—the student of the Shroud of Turin—more than the supposed mystery of how the image on the shroud was made. “It doesn’t look like any known work of art,” they say. The implication is that its creation was somehow miraculous, perhaps caused by a sudden burst of cosmic energy as the cloth came into contact with the dead body of Jesus. But in fact, it is simply historical ignorance of what the shroud really is (or at least, what it purports to be) that leads these people to wrongheaded notions. The Shroud of Turin is not, by definition, a work of art but instead belongs to the long and revered tradition of sacred objects that are at once relics and icons.

Such objects first appeared during the sixth century, in the Holy Land; in Greek they are called acheiropoietai (singular, acheiropoietos), which means “not made by human hands.” They are called this because they are (apparently) contact impressions of holy bodies. They have become relics through physical contact with the sacred, and they are icons because of the resultant image; but in neither case is there (by definition, at least) any intervention by an artist.

Among the earliest acheiropoietai is the Column of the Flagellation, in Jerusalem. This relic (the column) appears for the first time in fifth-century historical sources, which describe its location in the Church of Holy Sion; but it is only in the sixth century that pilgrims began to see the image of Jesus’ hands and chest impressed into its stone surface, left there, presumably, as Jesus was bound in place for the flagellation.

The most characteristic form of acheiropoietos, however, is the holy cloth. According to legend, St. Veronica stepped forward to wipe the sweat from Jesus’ brow as he stumbled toward Calvary, and her towel—already transformed into a relic through that holy contact—miraculously retained the image of Jesus’ face. Known as Veronica’s Veil, the relic became one of the most famous acheiropoietai of the Middle Ages.a Another such cloth image (also generated by perspiration) was produced on the night of the betrayal, as Jesus prayed intently at Gethsemane. And then there is the Shroud of Turin, seemingly produced by blood, blood plasma and sweat absorbed from Jesus’ dead body at the time of entombment (see the sidebar “The Shroud Painting Explained”).

Several reputed examples of each of these holy-icon cloths have surfaced over 028the centuries. At least three dozen cloths have been identified as Veronica’s Veil, the Holy Shroud, and the like. In 12th-century Constantinople alone, there were two iconic burial shrouds and one Gethsemane towel, each of which was eventually destroyed. What sets the Shroud of Turin apart is not what it is, but rather how it, almost alone among its object type, has survived more or less intact to modern times.

But the more important point is this: The Shroud of Turin is not and never was a “work of art” in the conventional sense of that term. And in fact, were it in any way to look like a work of art—something made by human hands—this would immediately disqualify it from being what it is supposed to be: an acheiropoietos.

This is the catch-22 that sindonologists fail to appreciate: For the shroud to be the shroud, it more or less has to look the way it looks. Furthermore, the shroud is in no way unique in appearance among its object type. The single salient quality that these sacred objects share is that very quality that is so striking about the shroud—namely, a faint and elusive image seemingly produced by bodily secretions.

How is it, finally, that we know for certain that the Shroud of Turin is a fake? Without prejudicing the possibility that one or more among history’s several dozen acheiropoietai may be genuine, we can be positive that this one cannot, since, according to its carbon 14 dating, it could not possibly have come into contact with the historical Jesus. Yet it would be incorrect to view the Shroud of Turin as just another icon, because it was very clearly, very self-consciously doctored in order to become what millions, until recently, have taken it to be: an image not made by human hands. And these, unlike icons, can only be one of a kind.

The Shroud of Turin was created to deceive. It was manufactured at a time, in western Europe especially, when relics meant pilgrimage and pilgrimage meant money. The competition for both, among rival cities and towns, was intense. And stealing and forgery were both part of the business.

It was also a time when the material remains of Jesus’ Passion were very much in vogue, when St. Louis would build Ste. Chapelle solely to enshrine the Crown of Thorns (which had recently been stolen from Constantinopole).

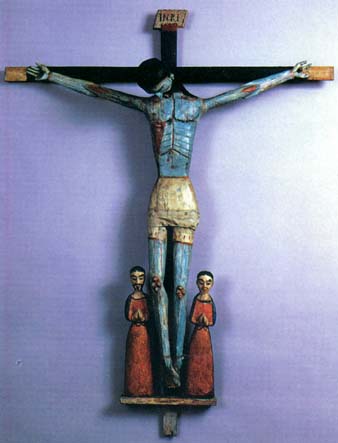

A contemporary model will help us understand this culture in which the blood and gore of Jesus’ death carried intense spiritual power. Although Emperor Constantine outlawed crucifixion in 315 A.D., the practice—as a form of piety—was never completely abandoned. To this day, some members of a lay confraternity of Spanish 029American Catholics in northern New Mexico, called the Penitentes, are said to practice various forms of extreme body mortification during Holy Week, including self-crucifixion. Thus, the Penitentes understand the physical reality of crucifixion as few before them have. The Penitentes are also known for their artwork; most characteristic are their carved wooden crucifixes, painted blue, which incorporate their firsthand knowledge of crucifixion—specifically, the knowledge that the body eventually turns blue from suffocation.

The carbon 14 dating of the shroud to 1260–1390 A.D. brings us into the world of the Penitentes’ patron saint, Francis of Assisi (who died in 1226), to his stigmata (the miraculous wounds on his hands, feet and side) and, especially, to the lay brotherhoods that his piety and his cult of self-mortification engendered. These Christians appreciated and understood Jesus’ wounds in a very physical way.

This is the world of the holy shroud; these are the people for whom it would have held special meaning; and these, certainly, are the people for whom it was made. Just as the Penitentes understand the significance of blueness, these medieval Christians would have understood that the nails must have gone through Jesus’ wrists in order to hold the body to the cross (although in medieval art these wounds are invariably in the palms). And their cult images would match this physical understanding of crucifixion, even to the point of adding human blood, much as the Penitentes add human hair and bone to their cult images. All of which is to say that the indication of nail holes in the wrists and what some claim is the presence of blood on the linen need not add up to a miracle.

Knowing both this and the shroud’s carbon 14 dating of 1260 to 1390 A.D., it is worth returning, finally, to the place and time of the shroud’s first appearance in historical documents. It is the year 1357, and the shroud is being exhibited publicly to pilgrims. It belongs to a French nobleman, Geoffrey de Charnay, and is being displayed in his private chapel in Lirey, a village near Troyes, in northeastern France. The Bishop of Troyes, Henri of Poitiers, is upset because he believes the shroud is a fake; in fact, he has been told this by a man who claims to have painted it. Thirty years pass. It is now 1389, and Henri’s successor, Pierre d’Archis, writes a long letter of protest about the shroud to Pope Clement VII. He recalls his predecessor’s accusation and then goes on to state his own conviction “that the Shroud is a product of human handicraft … a cloth cunningly painted by a man.” He pleads with the Pope to end its public display. The Pope’s written reply is cautious but clear; the shroud may still be displayed, but only on the condition that a priest be in attendance to announce to all present,

in a loud and intelligible voice, without any trickery, that the aforesaid form or representation [the shroud] is not the true burial cloth of Our Lord Jesus Christ, but only a kind of painting or picture made as a form or representation of the burial cloth.

This was the true verdict—the correct verdict—from the Pope, issued less than four decades after the shroud was painted. And isn’t it ironic that it has taken 600 years to get essentially the same answer—but this time from the offices of an international team of scientists?

When the Shroud of Turin went on display this spring for the first time in 20 years, it made the cover of Time magazine with the blurb “Is this Jesus?” In BAR, we summarized the controversy that has enshrouded this relic, venerated for centuries as the burial cloth of Jesus (“Remains to Be Seen,” Strata, BAR 24:04). Following Time’s lead, we reported that although radiocarbon tests have dated the shroud to 1260–1390 A.D., no one has been able to account for the shadowy image of a naked, 6-foot-tall man that appears on the shroud. With bloodstains on the back, […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username