039

As children we learn that A is for Apple, B is for Boy and C is for Cat, and that CAB is the machine we use to travel downtown. We also sing the alphabet song, whose words are the alphabetic signs sung in a sing-song rhythm that helps us to remember them all. We cannot imagine easily that pre-Greek systems of writing do not work that way at all. They do not tell us what words sound like. We do not know, for example, how Hebrew sounded in the days of Jesus, because the ancient Semitic system of writing simply does not tell us how to pronounce the words. You have to know already, just as we are taught to pronounce “A rough cough ploughed through a hiccough.”

To understand writing on Crete, and its place in history, we need to know something about the theory and history of writing, because we constantly run aground in thinking that writing in the ancient world worked in the same way that writing works for us. We also stumble over confusing terms applied unhistorically. For example, we often use the word “alphabet” to describe Phoenician writing, but this obscures the fact that an earth-shattering change took place around 800 B.C. when someone, either Greek or Semite, modified the Phoenician system to create the world’s first writing system that tells the reader what words sound like.a

Writing consists of markings of some kind on a material substance. These markings sometimes represent speech or parts of speech, but they may also communicate information through a raw symbol, like an arrow, or through a picture, like a handicapped-parking sign. What we most often think of as “real” writing, however, is phonetic writing, which refers to systems of writing in which at least some marks represent sounds of human speech.

When and where did phonetic writing first appear? On the best current evidence, it arose in Mesopotamia toward the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Mesopotamians had long been using small clay tokens of different shapes to represent commodities; for example, a token in the shape of a cone represented a small measure of grain. In the late fourth millennium B.C., they began representing tokens graphically (so the symbol for a small measure of grain became an inscribed triangle-like shape). Some ingenious person understood that the sounds of the shapes could be separated from their meanings in order to reproduce elements of human speech.b (For example, as I once noted in these pages, the sign for “bear” plus the sign for “reed” would give a pronounceable form of 040my first name: Barry. It is possible to make phonetic use of the entire sign, as in “bear,” or only a part of the sign, as in “reed.”) This discovery—that marks could be used to encode sound alone, without necessarily designating a thing or a quantity of things—was probably made to record personal names, which are essential to economic transactions.

Although phonetic writing is now attested in Egypt from around 3300 B.C., the Egyptian system, unlike the Mesopotamian system, had no local antecedents; the Egyptian writing must be derived from the still older Mesopotamian writing.

Writing on Crete and the outlying islands emerged around 1800 B.C., also under the influence of Mesopotamian traditions. Mesopotamian influence is evident not only in the ancient Cretans’ use of writing itself, but in the practice of writing on clay tablets. (The structuring of Minoan society around a central palace that controlled agricultural production and the distribution of commodities also closely parallels Mesopotamian models, as does the use of writing to serve this economic structure.) Nonetheless, the Cretans broke from older traditions of writing developed in Mesopotamia and Egypt. They may even have invented the first writing system consisting solely of phonetic signs.

Several scripts have been found on Crete, all of them belonging to the second millennium B.C. The oldest seems to be the so-called Cretan hieroglyphic script, found mostly on seal stones and seal impressions dating between 1800 and 1600 B.C. Arthur Evans, the British excavator of Knossos, called this semi-pictographic script “hieroglyphic” because it reminded him of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, but it has no evident connection to Egyptian writing. No doubt the writing encodes personal names, and it is probably a syllabic script, for the signs appear to follow one another in regular sequence.

The Cretan hieroglyphic script also appears on several clay tablets in a linear form, though it is a different form of writing from the so-called Linear A script, also found on Crete. The relationship between Linear A and Cretan hieroglyphic script is not clear; they appeared on Crete around the same time, but after about 1650 B.C. Cretan hieroglyphic script disappears. Many scholars assume that Linear A derives in some way from the hieroglyphic script, but there is not enough evidence to establish this connection to a certainty.

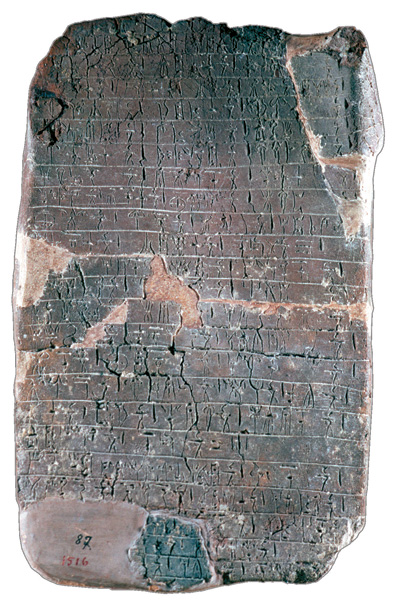

Neither the hieroglyphic script nor Linear A has yet been deciphered. We have about 200 examples of Linear A writing—mostly small, neatly inscribed clay tablets from southern Crete, many of them from the important center of Ayia Triadha. We assume—but do not know—that the script is syllabic, because of its similarity to a third and later script, Linear B, which has been deciphered.

Working backward from our knowledge of Linear B, we can draw some conclusions about Linear A documents. The document shown, for example, is an accounting tablet that reads from left to right. A vertical stroke represents “1” and a dot represents “10.” A check-mark sign (see the very last sign at the bottom right of the tablet) means “½,” and a circle means “100.” The top four signs on the tablet may designate a place-name. The first sign of the second row means “wine” in Linear B, which probably adopted the sign from Linear A. The second sign in the second row is preceded and followed by a dot. After that, we have six groups of signs, each followed by a numeral. It is therefore possible that the second sign in the second row (the sign with the dots on each side) means something like “paid out,” 041and that the following six groups of signs represent names of people or places receiving shipments of various quantities of wine. (For example, the signs opening the third line may mean something like: “Daidalos: 56 units.”) The writer is happy to break a name at the edge of the tablet and run it on to the next line (see the fifth line, for example). At the end of the tablet, the first two signs must mean something like “total” because the number “130½”—a circle, three dots and a check mark—is the correct total for the above tallies.

Curiously, then, we can thus offer a plausible interpretation of this unusually well-preserved tablet, but we cannot decipher it. To decipher a language you need one of three things: abundant comparative material, knowledge of the underlying language, or a bilingual inscription in which one of the languages is known (for example, the inscription on the Rosetta Stone—written in Egyptian hieroglyphic, Egyptian demotic and the Greek alphabet—allowed Jean-François Champollion to decipher hieroglyphics).

In the case of Linear A, we have none of the above. All we seem to know about its underlying language is that, unlike that of Linear B, it is not Greek. Take, for example, the word for “total,” which may well be meant by the first two signs in the last line of the inscription. In Linear B, the word for “total” has the phonetic value of to-so. In the Linear A inscription, however, the two signs for “total” have the phonetic value (determined by working backward from Linear B) of ku-ro, which cannot be explained as a Greek word. The signs very likely mean “total,” but in what language?

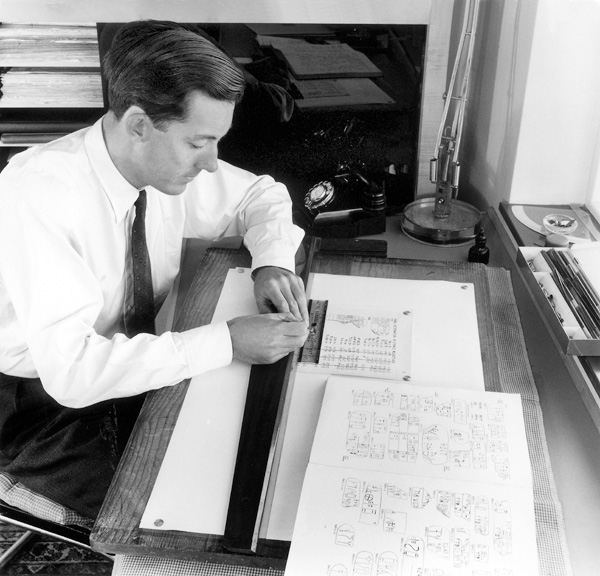

How, then, was Linear B deciphered? Although there is no bilingual text for Linear B and the underlying language was not known at the time, there was an abundance of comparative material—with more 042than 20,000 tablets surviving from Crete and the Greek mainland. In the 1950s, the brilliant English architect Michael Ventris, working with a repertory of signs established by the American scholar Emmett L. Bennett, Jr., and drawing on the American classicist Alice Kober’s work on variations in word endings, was able to construct a grid with vowels across the top and consonants down the side. Astutely guessing that certain place-names were the same in the classical period as in the Bronze Age, Ventris achieved real phonetic values for several signs. Plugging these values into the grid, the writing began to yield its secrets. To his and everyone’s astonishment, the writing proved to encode Greek.

Linear B was in use from about 1550 to 1200 B.C. Apparently the mainland Mycenaean Greeks occupied Crete and adapted local Cretan writing (Linear A) to record their own language. We can now read Linear B writing almost with facility. It is a syllabic script (meaning that its signs stand for syllables) of 59 signs; five of these signs stand for vowels and 54 stand for consonant-vowel combinations.

043

Linear B shares about 50 of its signs with Linear A, and all attempts to decipher Linear A have proceeded by substituting values of Linear B signs for Linear A signs. Although this is a reasonable starting point, it has not produced results, and there is no guarantee that it will. When signs from one linguistic context (Linear A) are used in another linguistic context (Linear B), they often change value, that is, acquire different meanings or functions. Whoever adapted Linear A to encode Greek most likely tried to preserve the sounds of the signs. But since we don’t know the underlying language, we cannot tell whether these phonetic groupings make linguistic sense. The method has not led to decipherment and is unlikely ever to do so.

Linear B, and apparently Linear A, also has a large repertory of sematographic signs, which are signs that stand for objects but do not have phonetic value and are never used as word signs in writing a sentence. In both Linear A and Linear B, these signs are used only as headings, so they are easy to discern. About 40 of the 60 sematographic signs in Linear A are also found in Linear B.

Linear B, like Linear A, is written from left to right, but it uses ruled lines to divide each line of text. Words are separated by a dot or a space, or by a change in size. It is important to emphasize that transcriptions of Linear B signs into Roman alphabetic characters (such as to-so, the word for “total” in Linear B) are entirely conventional and do not represent the real sounds such signs may have carried in ancient times. For example, the r-series of sounds—ra, re ri, ro, ru—simply represents a liquid consonant plus a vowel, however such a combination might have sounded on the lips of a Mycenaean Greek.

The table gives a transcription of some Linear B words. The first column gives Linear B signs; the second column provides the conventional transcription according to Ventris’s grid; the third column offers a reconstruction of how the word might have sounded in the Bronze Age; the fourth column gives the classical Greek word transliterated into Roman script; and the fifth column gives the meaning of the word.

042

|

Sign Sequence |

Transliteration |

Mycenaean Greek |

Classic Greek |

Word Meaning |

|

ku-mi-no |

kuminon |

kuminon |

cumin |

|

ku-na-ja |

gunaia |

gune |

woman (gynecology) |

|

ku-ru-so |

khrusos |

khrusos |

gold (chrysanthemum) |

|

pa-te |

pater |

pater |

father |

|

pa-ma-ko |

pharmakon |

pharmakon |

medicine (pharmacy) |

|

to-so |

toso |

tosos |

so many |

|

to-ra-ke |

thorakes |

thorax |

thorax |

|

qo-u- |

gwuo- |

bou- |

cow |

|

i-qo |

hikkwoi |

hippos |

horse |

|

re-u-ka |

leuka |

leukos |

white (leukemia) |

|

re-a |

rea |

rhis, rhino- |

nose (rhinoplasty) |

043

Some scholars have suggested that Linear B writing was abandoned around 1200 B.C. because it was unsuitable for the Greek language. However, it seems that all three of the Cretan scripts were used successfully for a very long period of time to manage the distribution of commodities. For this purpose two things were necessary: written signs for the names of those who exchanged a commodity (phonetic syllabic signs) and written signs for the kinds (and quantities) of commodities exchanged (sematographic signs). Linear B, and no doubt its predecessors, was very well designed to serve this function.

Casting away the non-phonetic elements that are so important to Mesopotamian writing, the inventor of Cretan writing fashioned a purely phonetic syllabary capable of recording the important sounds in the name of any person, place or thing. It is true that this syllabic system made use of sematographic signs designating commodities, but such signs were not part of the syllabic system itself. We moderns often combine phonetic and non-phonetic signs, too, as when we manufacture a red, octagonal street sign and write “STOP” on it as a phonetic clarification. In this respect, 060Linear B (and possibly Linear A) was superior to its cuneiform model, which was a complex mixture of phonetic and non-phonetic signs. Cretan syllabic scripts therefore represented a great advance in the technology of writing: a coherent, self-contained system of recording language.

What is striking is that a second such system of phonetic writing appeared around the same time (c. 1800 B.C.) in the Levant: the West Semitic family of scripts, which includes Phoenician, Hebrew and Aramaic. It seems likely that there is a connection between the Semitic and Cretan syllabic scripts, but we do not yet have any hard evidence.

None of the Cretan scripts lasted into the first millennium B.C. on Crete, though a related syllabic script was used on Cyprus until the fourth century B.C.c The Greek adaptation of West Semitic writing, on the other hand, has indeed been passed down to us, a form of which appears on the page you see before you. But West Semitic writing is based on the Egyptian writing system, which omits all information about qualities of vibration in the vocal chords—that is, it does not provide signs for vowels and therefore cannot be pronounced without oral instruction from a native speaker. In the early first millennium B.C., a Greek or Semitic scribe modified West Semitic writing, apparently to encode the sounds of Greek verse (perhaps even the sounds of Homer’s epics), by adding signs for vowels and the spelling rule that a sign for a consonant must be accompanied by a sign for a vowel.

Thus was born the first writing capable of representing a facsimile of the sound of the human voice: the Greek alphabet, matrix of Western culture.

As children we learn that A is for Apple, B is for Boy and C is for Cat, and that CAB is the machine we use to travel downtown. We also sing the alphabet song, whose words are the alphabetic signs sung in a sing-song rhythm that helps us to remember them all. We cannot imagine easily that pre-Greek systems of writing do not work that way at all. They do not tell us what words sound like. We do not know, for example, how Hebrew sounded in the days of Jesus, because the ancient Semitic system of writing […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See the exchange “Who Invented the Alphabet?” in Archaeology Odyssey, Premiere Issue, 1998: Barry B. Powell, “The Greeks”; P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., “The Semites.”

See Denise Schmandt-Besserat, “Signs of Life,” Origins, Archaeology Odyssey, January/February 2002.

See Pamela Gaber and William G. Dever, “The Birth of Adonis? Cyprus Excavation Suggests a Connection Between the Greek God and the Hebrew Adon,” Archaeology Odyssey, Spring 1998.