Destruction of Judean Fortress Portrayed in Dramatic Eighth-Century B.C. Pictures

Stunning new book assembles evidence of the conquest of Lachish

048

In the late eighth century B.C., Lachish was the second most important city in the kingdom of Judah. Only Jerusalem surpassed it.

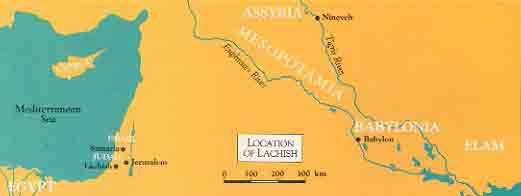

At that time, Assyria had risen to unprecedented power, dominating the known world. On the eve of Sennacherib’s accession to the Assyrian throne in 705 B.C., the Assyrian empire extended from Elam and Babylonia on the south, to Anatolia on the north, and to the Mediterranean Sea and the border of Egypt on the west.

Each year the Assyrians expanded their kingdom by a military expedition, often commanded by the king himself. Toward the end of the eighth century, the Assyrians began deporting subjugated peoples in order to blur their national identities.

Assyrian domination of the Land of Israel—then composed of the kingdom of Israel in the north and the kingdom of Judah in the south—proceeded step by step. By 732 B.C., Assyria had annexed the northern part of the kingdom of Israel. In 721/720 B.C., Assyria conquered the city of Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom, and annexed the rest of the kingdom of Israel, bringing a permanent end to its existence. The kingdom of Judah in the south would in all probability be the next target.

Soon after Sennacherib ascended the throne in 705 B.C., an anti-Assyrian alliance was formed by Egypt, the Philistine cities of the coastal plain and Judah, hoping to take advantage of the temporary weakness attendant on a change of monarchs. Judah at that time was ruled by one of the most prominent kings of the House of David, King Hezekiah.

By the time Sennacherib was ready for his third annual campaign—in 701 B.C.—he was able to direct his attention to the defiance of these three powers.

Many details of Sennacherib’s third campaign remain unclear, but two things are certain: although he laid siege to Jerusalem, for some reason or other, he was unable to conquer it; as a result, Judah remained a nation-state for more than a century afterward—until the Babylonians, who had destroyed the Assyrian empire, conquered Jerusalem in 587 B.C. Second, in his third campaign of 701 B.C., Sennacherib devastated much of Judah and utterly destroyed its second most important city, Lachish. As a result, King Hezekiah paid enormous tribute to Sennacherib, and Judah became to a large extent an Assyrian vassal state.

The destruction of Lachish is important not only historically, but also because it is uniquely documented. For no other ancient event of comparable significance is so much, and so many different kinds of, source material available. The events surrounding the conquest of Lachish, the destruction of the city and the deportation of its inhabitants are documented (or evidenced) in at least four independent contemporary sources: (1) in the Bible; (2) in Assyrian cuneiform accounts of the same events; (3) in archaeological excavations at the site of Lachish; and (4) remarkably, in monumental pictorial reliefs uncovered at Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh.

In a stunning new book by David Ussishkin, director of the most recent (and continuing) excavations at the mound of Lachish, material from these four sources is brought together to illuminate, as the title proclaims, The 049Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib.a

The text is not only lucid (it is written for the layperson as well as the scholar), it is also vivid and even dramatic. The book is superbly designed—it won first prize for design at the 1983 Jerusalem Book Fair—in a large format that permits the photographs and drawings to be displayed so that the viewer can see even small details without squinting. A special bonus is that the royal Assyrian reliefs depicting the battle of Lachish and the deportation of the Judean refugees have been rephotographed (by Avraham Hay) and redrawn (by Judith Dekel) from the originals in the British Museum. Dekel and another artist, Gert le Grange, have also reconstructed Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh as well as views of Lachishb and the 050battle waged against it in drawings based on all the available evidence.

From the Bible, we learn that during most of King Hezekiah’s reign (which began in 727 B.C.), Judah enjoyed a period of great prosperity, despite the fact that the kingdom of Israel to the north fell to the Assyrians (see 2 Chronicles 32:27–28). Hezekiah is also known for his important religious reforms. He strengthened Jerusalem and centralized worship in the Jerusalem Temple, abolishing all shrines and sanctuaries outside Jerusalem. Recent excavations in Jerusalem have shown that the city expanded greatly during his reign.1

The Bible also describes Sennacherib’s campaign in Judah, which ended with his unsuccessful siege of Jerusalem. To bring water into Jerusalem during the Assyrian siege, Hezekiah dug the famous tunnel that still bears his name. This tunnel may well have saved the city. According to the Bible, however, the siege was broken when the Lord killed 185,000 Assyrian soldiers in a single night, thus wiping out the bulk of Sennacherib’s army (2 Kings 19:35).

But before he foundered at Jerusalem, Sennacherib had been successful elsewhere. From the Bible we learn that he attacked “all the walled cities of Judah” (2 Kings 18:13; Isaiah 36:1). Three cities are mentioned by name 051in connection with this campaign—one of them is Lachish. In 2 Chronicles 32:9, we are told specifically that Sennacherib laid siege to Lachish. The conquest of Lachish obviously emboldened Sennacherib to try to overcome Jerusalem.

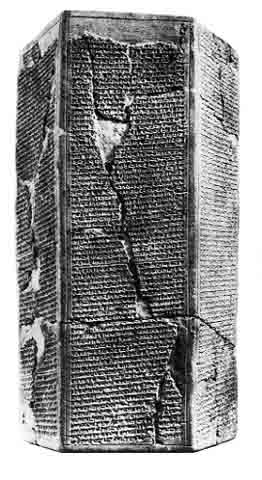

An Assyrian version of these events from Sennacherib’s own annals is contained on a 15-inch-high baked clay prism of six sides covered with Akkadian cuneiform. Three complete prisms with this text have been found. One, at the Israel Museum, is illustrated in this volume. The others are at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute and the British Museum. None was recovered in a controlled excavation.

In these annals, Sennacherib claims to have besieged and conquered 46 walled cities of Judah. Although he does not mention it by name, Lachish was surely one. Sennacherib describes his military strategy as follows: “I besieged and conquered by stamping down earthramps and then by bringing up battering rams, by the assault of foot soldiers, by breaches, tunneling and sapper operations.” Much of this strategy has been confirmed by excavations at Lachish and by the reliefs at Nineveh. Sennacherib claims that over 200,000 refugees came out of these cities, “Young and old, male and female … the spoils of war.”

Sennacherib also recounts how “Hezekiah the Jew … [was] shut up like a caged bird within Jerusalem, his royal city.” Pointedly enough, Sennacherib does not claim to have conquered or destroyed Jerusalem.

The first major excavations at Lachish were conducted between 1932 and 1938. The expedition came to an abrupt end, however, when its director, J. L. Starkey, was murdered by Arab marauders after his car was ambushed on the way from Lachish to Jerusalem. Starkey had been on his way to the opening ceremonies of the Palestine Archaeological Museum (now the Rockefeller Museum).

For many years after this excavation ended, the archaeological community did not agree on which level at Lachish represented Sennacherib’s destruction. Except for a small excavation in the 1960s, the mound remained untouched until 1973, when Ussishkin’s continuing excavations, sponsored by Tel Aviv University and the Israel Exploration Society, began. These excavations have now settled, to the satisfaction of almost all scholars, that Level III at Lachish represents the city destroyed by Sennacherib (see “Answers at Lachish,” BAR 05:06).

From the archaeological evidence, it is clear that during Hezekiah’s reign Lachish was a large garrison city, a formidable royal citadel that boasted a huge palace-fort as 052well as residences. The city was surrounded by a massive wall with towers and battlements.c A great gate complex consisting of an outer gate and an inner gate controlled access to the city. The inner gatehouse, as uncovered by the archaeologists, is a massive structure, the largest of its kind ever found in Israel. It is approximately 75 feet square and consists of four piers on either side. In the ashy debris left from Sennacherib’s destruction—near the outermost pier—the excavators collected numerous pieces of bronze that had once been part of the bronze fittings on the large wooden doors of the gatehouse. Chunks of carbonized wood were all that could be found of the doors themselves.

Several long narrow buildings in the city can be interpreted either as storehouses or as stables for government cavalry. The scholarly world is still divided as to the correct interpretation of these buildings (see “Megiddo Stables or Storehouses?” BAR 02:03). Ussishkin himself takes no position on this subject.

The Assyrians mounted their siege of the city from the southwest. Topographically this makes sense: The mound is most vulnerable at a “saddle” at its southwest corner where the city gate was located. (See “News from the Field: Defensive Judean Counter-Ramp Found at Lachish in 1983 Season,” in this issue, by excavator Ussishkin.)

The Assyrians made their camp on a hillock opposite the gate, near enough for Sennacherib himself to direct the battle but far enough away to be out of range of the defenders’ missiles. The southwest corner of the mound of Lachish has revealed ample evidence of a ferocious battle, although the stratigraphy is not clear enough to allow the archaeologists to attribute all this evidence to Sennacherib’s attack.

053

To clear the ancient roadway leading up to the gate, the expedition in the 1930s removed immense quantities of stone—“many thousands of tons,” according to Starkey. In 1973, Yigael Yadin visited the site and suggested that these heaps of stones might be the remains of the Assyrian siege ramp. Ussishkin checked the possibility by further excavation and, in 1977, concluded that “the only convincing and logical interpretation of these stones is that they were used to build a siege ramp.” The siege ramp was relatively wide, fanning out at the base and narrowing at the top where it reached the city wall. The stones in the upper layer of the siege ramp were cemented together with mortar. Although such siege ramps were no doubt common in antiquity, this is the only Assyrian siege ramp to have been identified in an archaeological excavation. Indeed, it is the oldest siege ramp found anywhere in the Near East.

The city of Level III at Lachish was burned to the ground by the conquering Assyrians. Ussishkin believes that the Assyrians first looted the city and forced all the inhabitants to leave. Excavators found the floors of the burned buildings strewn with smashed pottery vessels, but there were no valuables or human skeletons. The people must have left before the Assyrians put the city to the torch. In that conflagration, the buildings’ sun-dried mud-bricks were baked by the fire and turned red. In some places, the piles of burned bricks were six feet high and were covered by ashes from the roofs. We can easily imagine Assyrian soldiers brandishing their torches and lighting whatever would burn—a wooden roof beam, a straw mat, a storage jar full of oil.

Hundreds of arrowheads were found in the excavation, especially where the battle raged, although not all can be said to have come from Level III. Some of the 054arrows shot by the Assyrians stuck in the superstructure of the inner gate; the arrowheads were found still stuck in place amid the destruction debris.

Slingstones, another type of ammunition, were also found in large quantities. The slingstones are mostly round balls of flint about 2.4 inches (6 cm) in diameter.

More than 20 pieces of scale armor, mostly bronze but some iron, were also uncovered.

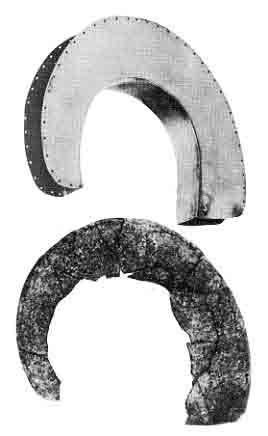

Among Starkey’s unique finds was a bronze crest mount from an Assyrian helmet. Attached to the crest were remnants of cloth and leather fastenings and the rivets that held the mount in place. Ussishkin allows himself to ruminate: “Is it possible we have here the helmet of an Assyrian spearman who was killed while attempting to ascend the walls?” He allows also for the possibility, suggested by fellow archaeologist Gabriel Barkay, that the crest might have been part of the finery of a chariot horse.

Finally, we come to the evidence from the Assyrian reliefs. Here we have the battle of Lachish depicted in what must be the closest thing to an ancient movie—scene after scene carved into stone—from the phalanxes prepared for battle to the deportation of the conquered Judeans.

056

The reliefs were found in the ancient city of Nineveh, located on a tell that rises nearly 50 feet above its surroundings on a plain opposite Mosul, Iraq. Nineveh is described in the book of Jonah as “that great city with more than 120,000 people who cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle” (Jonah 4:11).

Although it had been settled since the fifth millennium B.C., Nineveh became the capital of the Assyrian empire only after Sennacherib’s accession to the throne. In Sennacherib’s day, the massive walls that encircled the city extended for nearly eight miles (13 km) and contained 15 magnificent gateways. Inside, Sennacherib built a variety of wide avenues lined with stelae, large public squares, streets, public buildings and palaces. A remarkable canal 48 miles (80 km) long with a 1,000-foot aqueduct (which is still standing) supported on five pointed arches carried water from the Gomel River to maintain the city’s luxuriant gardens of rare and exotic plants.

Shortly after his conquest of Lachish, Sennacherib decided to build himself a new palace. He completed the project in 694 B.C. As we learn from Sennacherib’s annals, the palace was built with forced labor gangs composed of foreign captives and deportees, those from Judah—very possibly including people from Lachish—among them. In his annals, Sennacherib calls his new palace the “Palace Without a Rival.” Its construction was undoubtedly a major architectural enterprise.

Unfortunately, the palace was partially burned and destroyed in the internal disorders that followed Sennacherib’s death in 681 B.C. (The conqueror of Lachish was murdered by his own sons; see 2 Kings 19:37, Isaiah 37:38, 2 Chronicles 32:21.) The empire then began a slow decline, which soon developed into a rapid disintegration. Finally, in 612 B.C. Nineveh was conquered and destroyed by the Babylonians and the Medes, and Sennacherib’s palace was again burned. In 609 B.C. the Assyrian empire, once the ruler of the world, collapsed.

With the decline of Assyria, Lachish once again be came part of the Land of Israel and was rebuilt, probably by King Josiah (639–609 B.C.). Nineveh, by contrast, remained an abandoned ruin forever, as prophesied by Nahum and Zephaniah (2:13): “He will make Nineveh a desolation and dry like a wilderness.”

057

“Is this the gay city

That dwelt secure,

That thought in her heart

‘I am, and there is none but me’?

Alas, she is become a waste,

A lair of wild beasts!

Everyone who passes by her

Hisses and gestures with his hand.”

(Zephaniah 2:15, NJPS translation)

Thus Nineveh.

Nineveh was first excavated by the famous 19th-century English archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1846 and 1847. A few days after he began his second season, Layard came upon a room in the “Palace Without a Rival” that was lined with reliefs. Within a month, he discovered nine such rooms. By 1849, the extensive cuneiform inscriptions in the palace had been sufficiently deciphered to identify the name of Sennacherib. In that same year, Layard returned to the mound. Excavating the palace was a gigantic task that Layard accomplished by digging tunnels along those walls decorated with reliefs. Although this method would be unforgivable today, it was effective for its time. Layard continued excavating at Nineveh until 1851 and succeeded in unearthing large sections of the palace.

Layard himself described the work:

“In this magnificent edifice, I had opened no less than seventy-one halls, chambers and passages, whose walls, almost without exception, had been paneled with slabs of sculptured alabaster recording the wars, the triumphs, and the great deeds of the Assyrian king.”

In 1853 most of the reliefs were removed from Nineveh and sent to the British Museum in London, where they are now displayed.

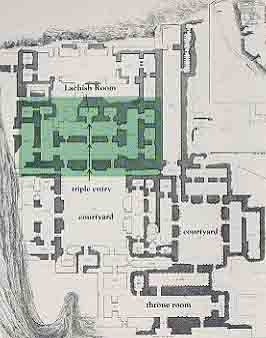

The “Palace Without a Rival” was of course the most important building in Nineveh. Its most magnificent feature was a large ceremonial suite whose focal point was a single room approached through three monumental portals built on a straight axis. Colossal statues of winged bulls stood at each portal, but the statues were successively smaller, thus conveying the impression to someone standing at the outer entrance that the focal room was much further away than it actually was.

The reliefs that lined the wall of this focal room commemorated the conquest of Judah and Sennacherib’s victory at Lachish. We may properly call it the Lachish Room. The section of the reliefs portraying the storming of Lachish was placed on the wall opposite the entrance, making this section the focal point of the entire work and giving some idea of the importance Sennacherib attached to his conquest of this great Judean stronghold. It was apparently the crowning military achievement of his entire career.

In Ussishkin’s book the reliefs are magnificently presented in long pullout pages, in photographs and in drawings, in extenso and in detail. Without doubt, they can be more easily and more understandably studied here than 059from the originals in the British Museum.

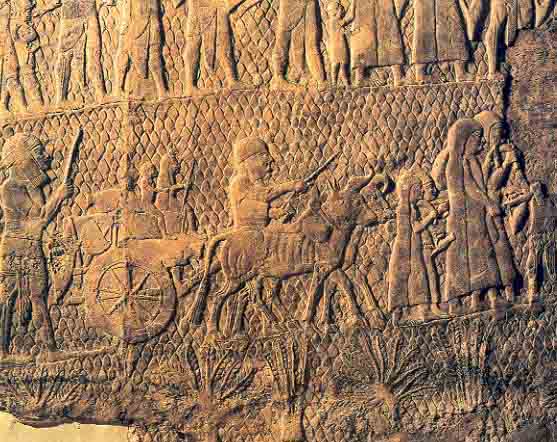

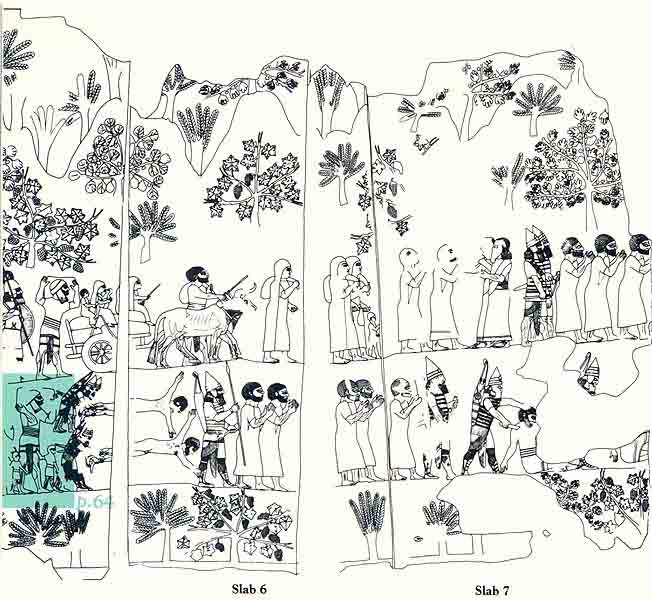

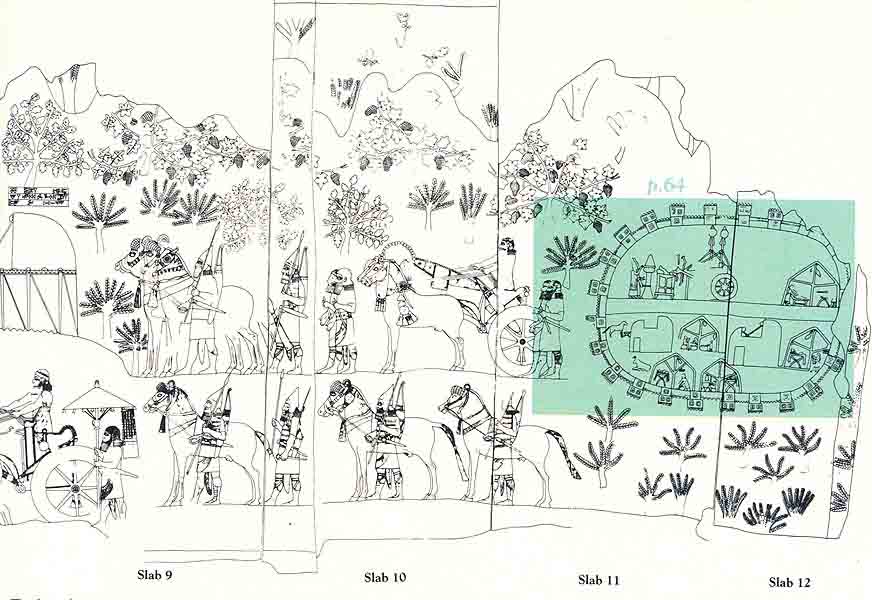

The uniform background of the reliefs is a pattern of overlapping wedges resembling scale armor or fishscales. Ussishkin interprets it as representing the stony landscape of the Lachish region. Against this backdrop, the battle unfolds in a magnificent panorama that moves through space and time.

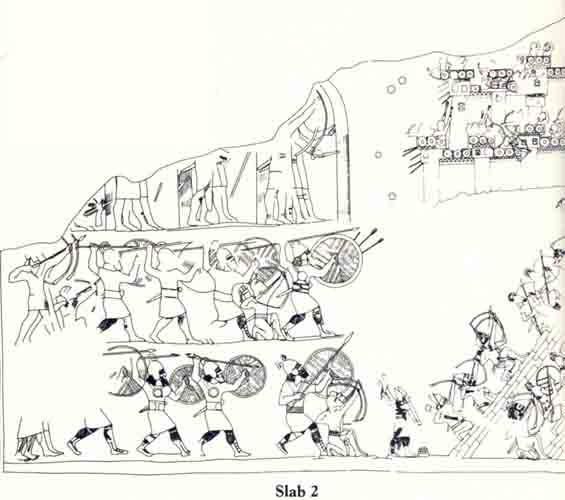

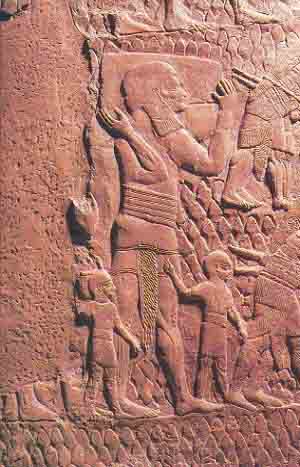

Beginning on the left, three lines of Assyrian soldiers march two abreast, approaching the city of Lachish. In front are the archers with their composite bows. At the rear are pairs of slingers, whirling their slings around their heads. Heaps of slingstones lie at the feet of the slingers in the upper row. Each contingent of soldiers is dressed distinctly. Some have beards and long hair held in place by headbands or scarves. Sometimes a fringed edge hangs down and covers the cheek. Some soldiers wear short skirts and wide belts. These distinctions in dress probably identify different ethnic divisions of the Assyrian army.

Further to the right (on the second slab) we see the Assyrian spearmen, each with a round shield in his left hand. The spearmen have long curly hair, long beards and wear pointed helmets with earflaps. Each has a sword thrust through his wide belt. Arrows from the city’s defenders are stuck in the shield of the foremost spearman in the upper row. The battle for Lachish has begun.

The portrayal of the besieged city extends over three slabs, beginning with the right side of the second slab. In this scene the city walls are depicted at a higher level than the advancing troops. The besieged city is approached by a steep incline emphasizing the city’s elevation.

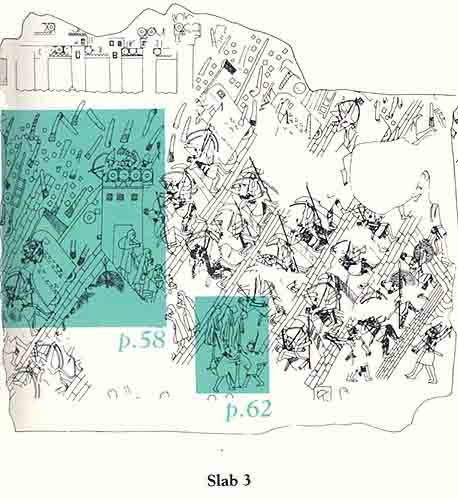

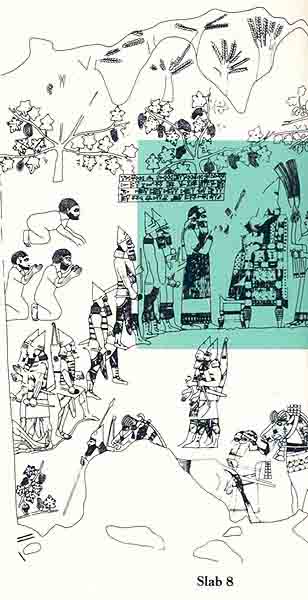

The focal point of the third slab is the city gate, which is being stormed. From the archaeological excavation of 063the Assyrian siege ramp, we would not know it, but from the reliefs at Nineveh we see quite clearly that the ramp is covered with log tracks. Several such tracks are pictured leading up to the walls of Lachish. On some are formidable Assyrian battering rams or siege machines, in effect mobile assault towers. The most clearly depicted battering ram appears on the third slab. The ram approaches the city gate on spoked wheels that are partly covered by the body of the machine. The machine was apparently constructed of prefabricated parts assembled on the site with securing pins. The body of the siege machine has a turret with a window. The ram itself, resembling a large spear, extends from the front of the machine. The shaft of the ram must have hung from ropes inside the machine. Men on the floor of the machine would push the ram forward in great strokes, waiting for it to swing back before repeating the action. Thus the ram would pound systematically against a carefully selected weak point in the wall until eventually the ram broke through.

The Judean defenders of Lachish—on the walls of the city—can be seen attempting to set fire to the entire machine, which was probably made of flammable leather and wood, by showering it with firebrands. As a countermeasure, an Assyrian soldier standing in the back of the machine, partly exposed and partly protected by the turret, pours water over the machine and the shaft of the ram using what looks like an enormous ladle.

At least seven battering rams attack Lachish, the largest number of battering rams shown in any Assyrian relief of an attack on a single city.

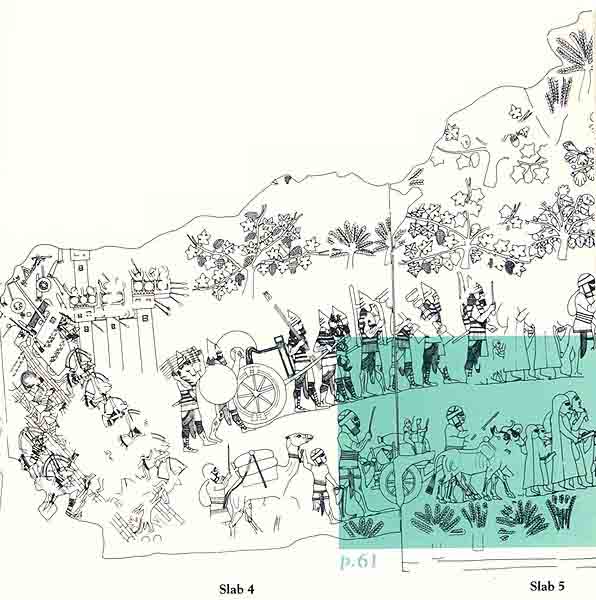

In what must have been intended as a later scene, we see a line of Judean refugees coming out of the city gate after the surrender of Lachish. In this and the following scenes, we have the only surviving pictures of eighth-century B.C. Judeans—men, women and children.

Closest to the city gate are two Judean women wearing long dresses. Shawls cover their heads. A bag with belongings hangs over the shoulder of each woman. They may hold jugs of water in their right hands. Ahead of them are two Judean men clad in short tunics with belts. They wear headscarves that hang down.

At the bottom of the siege ramp in front of the gate, three Judean prisoners, stripped naked, have been impaled on stakes. The heads of the men sag forward, indicating they are already dead. Two Assyrian spearmen wearing helmets with crests—like the one Starkey found in the Lachish excavations—secure the stake on which the slain Judean defender at the right has been impaled.

Beginning on the fourth slab are two columns of people to the right of the city. In the upper row, Assyrian soldiers carrying booty walk behind some Judean deportees. The 064spoil of war carried by the first Assyrian soldier in the back group is a scepter or mace pointing, probably deliberately, downward—a symbol of authority conquered. The fourth soldier in the group carries a chair with rounded top and armrests. This must have been the seat of state of the governor of Lachish. Behind this, several Assyrian soldiers pull what must have been the official chariot of the royal governor of Lachish. This is the only documented depiction of a Judean chariot. It closely resembles Assyrian chariots of the period.

Further forward in this row and in the bottom row are touching scenes of Judean deportees—men, women and children. In one family in the upper row, we see the father leading a cart drawn by two oxen. The ribs of the oxen are emphasized, perhaps to indicate their malnutrition. The cart is laden with household goods. On top sit two women and two children, one in arms. Both men and women are barefoot. Other small children, both behind and in front of this scene, are walking to exile, one child’s hand held in that of a parent walking alongside.

Beneath this scene, in the bottom row, as well as in front of this scene in the top row, is a group of guarded Judean prisoners who have been identified by the-prominent British scholar, Richard D. Barnett, as “Hezekiah’s men,” the king’s soldiers who may have led the resistance at Lachish. Hence, they are treated more harshly. They have curly hair and short, curly beards. They walk, also barefooted, with their hands upraised in a plea for mercy. 065Some kneel and crouch as they approach Sennacherib on his battle throne. Others are being tortured. Two Judeans in the bottom row are portrayed lying on the ground, stripped naked with outflung arms, while Assyrian archers hold their ankles. Apparently the Judean prisoners have just been flayed alive. In the upper row an Assyrian soldier holds a Judean captive by his hair and stabs him in the shoulder with a dagger or short sword.

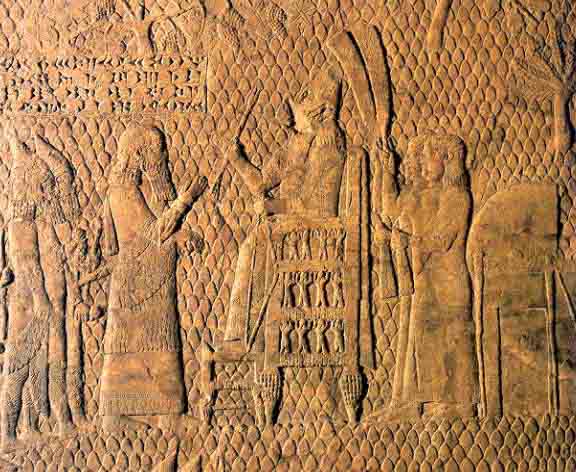

The two lines of Assyrian soldiers and Judean captives lead to the seated figure of Sennacherib himself. The monarch sits on his battle throne in front of his personal tent, facing the now conquered city. A cuneiform inscription just in front of and above the king reads: “Sennacherib, king of all, king of Assyria, sitting on his nimedu-throne while the spoil from the city of Lachish passed before him.” (The king’s face has been deliberately mutilated by those who came after him, presumably his murderers.)

Further to the right, the Assyrian camp is depicted as an oval. Today an Israeli moshav, or cooperative village, is situated where the Assyrian camp once stood. Ussishkin believes it was from this vantage point that the Assyrian artist who created the reliefs watched the battle that destroyed Lachish in 701 B.C.

In the late eighth century B.C., Lachish was the second most important city in the kingdom of Judah. Only Jerusalem surpassed it. At that time, Assyria had risen to unprecedented power, dominating the known world. On the eve of Sennacherib’s accession to the Assyrian throne in 705 B.C., the Assyrian empire extended from Elam and Babylonia on the south, to Anatolia on the north, and to the Mediterranean Sea and the border of Egypt on the west. Each year the Assyrians expanded their kingdom by a military expedition, often commanded by the king himself. Toward the end of the […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Publications of The Institute of Archaeology No. 6, 1982, 135 pp., 13 × 13 inches, $72.

One or two scholars still question the identity of Lachish. See, most recently, G. W. Ahlström, “Tell ed-Duweir: Lachish or Libnah?” Palestine Exploration Quarterly (July–December 1983). Ussishkin finds the identification for the site of Lachish “weighty.”

From the reliefs and the excavations, it has been assumed that two walls surrounded Lachish. Ussishkin believes only one wall protected the city. The supposed outer wall was, in his view, a strong revetment retaining the bottom of a glacis, which in turn supported the base of the city wall itself. What appears in the reliefs to be the outer wall, Ussishkin suggests, are battlements and parapets erected on the revetment wall to provide additional positions for soldiers manning the first line of defense.