Christianity is a religion of the book. From the outset, it has stressed specific texts as authoritative scripture. Yet not one of these original, authoritative texts exists today. We have only late copies, dating from the second century to the sixteenth. And these copies vary considerably. Indeed, the 5,700 manuscripts of the Greek New Testament that have been catalogued contain more variations than there are words in the New Testament. Some scholars say there are 200,000 variant readings, others say 300,000, 400,000 or even more!

Some variant readings are simply scribal mistakes. Others are editorial “improvements” intended to make the text easier to understand. Still others are deliberate attempts by the scribes to make the texts more amenable to the doctrines being espoused by Christians of their own persuasion and to eliminate the possible “misuse” of the texts by Christians affirming heretical beliefs.1

Most of the variants are insignificant, of no real importance for anything other than showing that scribes could not always spell or keep focused. But in some instances, the variants have a real bearing on the meaning of the text. Two intriguing examples are found in Mark 1, involving the healing of a man with a skin disease (often translated “leprosy”), and in Luke 22, the account of Jesus’ agony in the garden. In both cases, modern translators have generally opted for what I believe is the wrong variant reading. In other words, almost everyone who reads the New Testament in English has been misreading these key passages.

The surviving manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark preserve verse 41 of chapter 1 in two different forms. Both readings are shown here, in brackets:

39And he came preaching in their synagogues in all of Galilee and casting out the demons. 40And a leper came to him beseeching him and saying to him, “If you wish, you are able to cleanse me.” 41And [“feeling compassion” or “becoming angry”], reaching out his hand, he touched him and said, “I wish, be cleansed.” 42And immediately the leprosy went out from him, and he was cleansed. 43And rebuking him severely, immediately he cast him out; 44and he said to him, “See that you say nothing to anyone, but go, show yourself to the priest and offer for your cleansing that which Moses commanded as a witness to them.” 45But when he went out he began to preach many things and to spread the word, so that he [Jesus] was no longer able to enter publicly into a city.

(Mark 1:39–45)

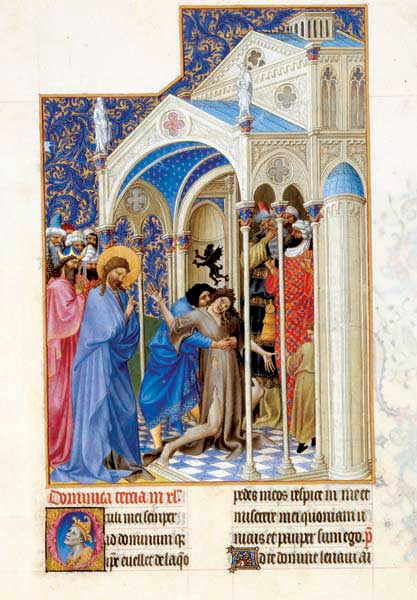

Most English translations render the beginning of verse 41 so as to emphasize Jesus’ love for this poor outcast leper: “feeling compassion” (the Greek used here, SPANGNISTHEIS, could also be translated “moved with pity”) for him. It is certainly easy to see why compassion might be called for in the situation. We don’t know the precise nature of the man’s disease—many commentators prefer to think of it as a scaly skin disorder rather than the kind of rotting flesh that we commonly associate with leprosy.a In any event, he may well have fallen under the injunctions of the Torah that forbade “lepers” of any sort to live normal lives: They were considered unclean, and were to be isolated, cut off from the public (Leviticus 13–14). Moved with pity for such a one, Jesus reaches out a tender hand, touches his diseased flesh and heals him.

The simple pathos and unproblematic emotion of the scene may well account for the fact that translators and interpreters, as a rule, have not considered the alternative text found in some of our manuscripts. The wording of one of our oldest Greek witnesses, the fifth-century Codex Bezae (named after Theodore Bezae, who in 1581 gave the manuscript to the University of Cambridge, where it still resides), supports the alternative reading. And Codex Bezae is supported by three ancient Latin manuscripts. Here, rather than saying that Jesus felt compassion for the man, the text indicates that he became angry (ORGISTHEIS). Because of its attestation in both Greek and Latin witnesses, this alternative reading is generally conceded by textual specialists to go back at least to the second century. Is it possible, though, that this is what Mark himself wrote?

Since most extant manuscripts use the term “compassion,” it is tempting to count noses, so to speak, and give preference to this popular variant. Most scholars today, however, are not at all convinced that the majority of manuscripts necessarily provide the best available text. In part, this is because the vast majority of our manuscripts were produced hundreds and hundreds of years after the originals, and they themselves were copied not from the originals but from other, much later copies. Once a change made its way into the manuscript tradition, it could be perpetuated until it became more commonly transmitted than the original wording.

One other consideration is the age of the manuscripts that support a reading. It is far more likely that the original form of the text will be found in the oldest surviving manuscripts—on the premise that the text gets changed more frequently with the passing of time. This is not to say that one can blindly follow the oldest manuscripts in every instance, of course. This is for two reasons, the one a matter of logic and the other a matter of history.

In terms of logic, suppose a manuscript of the fifth century has one reading, but a manuscript of the eighth century has a different one. Is the reading found in the fifth-century manuscript necessarily the older form of the text? Not necessarily. What if the fifth-century manuscript had been produced from a copy of the fourth century, but the eighth-century manuscript had been produced from one of the third century? In that case, the eighth-century manuscript would preserve the older reading.

The second, historical, reason that one cannot simply look at the oldest manuscript, with no other considerations, is that the earliest period of textual transmission was also the least controlled.

That’s because in the first three centuries of Christianity, most of the copyists of the Christian texts were not professionals trained for the job but simply Christians of this or that congregation who were able to read and write, and so were called upon to reproduce the texts in their spare time. Because they were not highly trained or experienced, they were more prone to making mistakes.

Professional scribes probably began copying New Testament manuscripts only in the fourth century, after the Roman emperor Constantine converted to the faith and Christianity suddenly shifted from being a minor religion of social outcasts to being a major player in the religious scene of the empire.

More and more highly educated and trained persons converted to the faith. They, naturally, were the ones most suited to copying the texts of the Christian tradition. It appears that around this same time Christian scriptoria (places for the professional copying of manuscripts) arose in major urban areas.2 The texts they produced were increasingly clean and consistent.

One factor in favor of the “angry” reading is that it sounds wrong. If Christian readers today were given the choice between these two readings, no doubt almost everyone would choose the one more commonly attested in our manuscripts: Jesus felt pity for the man, and so he healed him. The other reading is difficult to figure out. What would it mean to say that Jesus felt angry?

But the fact that one of the readings makes such good sense and is easy to understand is precisely what makes some scholars suspect that it is the error. For scribes also would have preferred the text to be nonproblematic and simple to understand. The question is, Which is more likely: that a scribe copying this text would change it to say that Jesus became wrathful instead of compassionate, or to say that Jesus became compassionate instead of wrathful? Which reading better explains the existence of the other? When seen from this perspective, the “angry” Jesus is obviously more likely.

There is even better evidence than this speculative question of which reading the scribes were more likely to invent. It comes from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Remember, just twenty years after Mark wrote his gospel (but long before any of our extant gospel manuscripts were produced), Matthew and Luke used Mark’s account as a source for their own stories about Jesus.3 It is possible, then, to examine Matthew and Luke to see what they made of this story.

Matthew and Luke both took over this story from Mark. It is striking that Matthew (8:2–4) and Luke (5:12–16) are almost word for word the same as Mark in the leper’s request and in Jesus’ response in verses 40–41. Which word, then do they use to describe Jesus’ reaction? Does he become compassionate or angry? Neither. Oddly enough, Matthew and Luke omit the word altogether.

If the text of Mark available to Matthew and Luke had described Jesus as feeling compassion, why would each of them have omitted the word? Both Matthew and Luke describe Jesus as compassionate elsewhere, and whenever Mark has a story in which Jesus’ compassion is explicitly mentioned, one or the other of them retains this description in his own account.4

What about the other option? What if both Matthew and Luke read in Mark’s gospel that Jesus became angry? Would they have been inclined to eliminate that emotion? There are, in fact, other occasions on which Jesus becomes angry in Mark. In each instance, Matthew and Luke have modified the accounts. In Mark 3:5 Jesus looks around “with anger” at those in the synagogue who are watching to see if he will heal the man with the withered hand. Luke 6:10 has the verse almost the same as Mark, but he removes the reference to Jesus’ anger. Matthew 12:13 completely rewrites this section of the story and says nothing of Jesus’ wrath (see also Matthew 19:14; Luke 18:16).

In sum, Matthew and Luke have no qualms about describing Jesus as compassionate, but they never describe him as angry. Whenever one of their sources (Mark) did so, they both independently rewrote the term out of their stories. Thus, whereas it is difficult to understand why they would have removed “feeling compassion” from the account of Jesus’ healing of the leper, it is easy to see why they might have wanted to remove “feeling anger.” Combined with the circumstance that the latter term is attested in a very ancient stream of our manuscript tradition and that scribes would have been unlikely to create it out of the much more readily comprehensible “feeling compassion,” it is becoming increasingly evident that Mark, in fact, described Jesus as angry when approached by the leper to be healed.

At what, though, would Jesus be angry? This is where the relationship of text and interpretation becomes critical. Some scholars who have preferred the text that says Jesus “became angry” have come up with highly improbable interpretations. They attempt to exonerate Jesus by making him look compassionate even though they realize that the text says he became angry.5 One commentator, for example, argues that Jesus is angry with the state of the world that is full of disease; in other words, he loves the sick but hates the sickness. Another interpreter argues that Jesus is angry because this leprous person had been alienated from society, but this overlooks the fact that the text says nothing about the man being an outsider and that it would not have been the fault of Jesus’ society but of the Law of God (specifically, in Leviticus). Another argues that, in fact, that is what Jesus was angry about, that the Law of Moses forces this kind of alienation. This interpretation ignores the conclusion of the passage, in which Jesus affirms the Law of Moses and urges the former leper to observe it: “Go, show yourself to the priest and offer for your cleansing that which Moses commanded” (Mark 1:44).

All these interpretations have in common the desire to exonerate Jesus’ anger and willingness to ignore what the text really says. Should we opt to do otherwise, what might we conclude?

First, we should note that in the opening part of Mark’s gospel Jesus does not come off as the meek-and-mild, soft-featured, Good Shepherd of the stained-glass window. Rather, Mark begins his gospel by portraying Jesus as a physically and charismatically powerful authority figure who is not to be messed with. Jesus is introduced by a wild-man prophet in the wilderness (1:4–8); he is cast out from society to do battle in the wilderness with Satan and the wild beasts (1:12–13); he returns to call for urgent repentance in the face of the imminent coming of God’s judgment (1:14–15); he rips his followers away from their families (1:20); he overwhelms his audiences with his authority (1:27); he rebukes and overpowers demonic forces that can completely subdue mere mortals (1:27, 34); and he refuses to accede to popular demand, ignoring people who plead for an audience with him (1:36–38).

It is possible that Jesus is being portrayed in the opening scenes of Mark’s gospel, including the scene with the leper, as a powerful figure with a strong will and an agenda of his own, a charismatic authority who doesn’t like to be disturbed.

There is another explanation, though. As I’ve indicated, Jesus does get angry elsewhere in Mark’s gospel. The next time it happens is in chapter 3, which involves, strikingly, another healing story. Here Jesus is explicitly said to be angry at Pharisees who think that he has no authority to heal the man with a crippled hand on the Sabbath.

In some ways, an even closer parallel comes in a story in which Jesus’ anger is not explicitly mentioned but is nonetheless evident. In Mark 9, when Jesus comes down from the Mount of Transfiguration with Peter, James and John, he finds a crowd around his disciples and a desperate man in their midst. The man’s son is possessed by a demon, and he explains the situation to Jesus and then appeals to him: “If you are able, have pity on us and help us.” Jesus fires back an angry response, “If you are able? Everything is possible to the one who believes.” The man grows even more desperate and pleads, “I believe, help my unbelief.” Jesus then casts out the demon.

In each of these stories, Jesus’ anger erupts when someone doubts his willingness, ability or divine authority to heal. Maybe this is what is involved in the story of the leper as well. As in the story of Mark 9, someone approaches Jesus gingerly to ask: “If you are willing you are able to heal me.” Jesus becomes angry. Of course he’s willing, just as he is able and authorized. He heals the man but, still somewhat miffed, rebukes him sharply and throws him out.

In Mark, Jesus gets angry. In Luke, he does not. In fact, Luke’s Jesus never appears disturbed at all. He is imperturbable. There is only one passage in this gospel in which Jesus appears to lose his composure. And this brings us to our second passage, Luke 22:43–44, the authenticity of which is hotly debated among textual scholars.6

Jesus is praying on the Mount of Olives just before he is betrayed and arrested (Luke 22:39–46). After enjoining his disciples to “pray, lest you enter into temptation,” Jesus leaves them, drops to his knees and prays:

Father, if it be your will, remove this cup from me. Except not my will, but yours be done.

(Luke 22:42)

In a large number of manuscripts the prayer is followed by the account, found nowhere else in the Gospels, of Jesus’ heightened agony and so-called bloody sweat:

And an angel from heaven appeared to him, strengthening him. And being in agony he began to pray yet more fervently, and his sweat became like drops of blood falling to the ground.

(Luke 22:43–44)

The scene closes with Jesus rising from prayer and returning to his disciples to find them asleep. He then repeats his initial injunction to them: “Pray, lest you enter into temptation.” Immediately Judas arrives with the crowds, and Jesus is arrested.

The manuscripts that are known to be the earliest and that are generally conceded to be the best (the “Alexandrian” text) do not, as a rule, include the passage about Jesus’ so-called bloody sweat (Luke 22:43–44). So perhaps they are a later, scribal addition. On the other hand, the verses are found in several other early textual witnesses and are, on the whole, widely distributed throughout the entire manuscript tradition. So were they added by scribes who wanted them in or deleted by scribes who wanted them out? It is difficult to say on the basis of the manuscripts themselves.

Some scholars have proposed that we consider other features of the verses to help us decide. One scholar, for example, has claimed that the vocabulary and style of the verses are very much like what is found elsewhere in Luke: For example, appearances of angels are common in Luke, and several words and phrases found in the passage occur in other places in Luke but nowhere else in the New Testament (such as the verb for “strengthen”). The argument hasn’t proved convincing to everyone, however, since most of these “characteristically Lukan” ideas, constructions and phrases are either formulated in uncharacteristically Lukan ways (for example, all the other angels in Luke speak but this one doesn’t) or are so common in Jewish and Christian texts outside the New Testament that their appearance in Luke’s gospel is not particularly surprising or significant. Moreover, there is an inordinately high concentration of unusual words and phrases in these verses: For example, three of the key words (“agony,” “sweat” and “drops”) occur nowhere else in Luke, nor are they found in Acts (the second volume by the same author). In sum, it is difficult to authenticate these verses on the basis of their vocabulary and style.

Another argument scholars have used has to do with the literary structure of the passage, which appears to be deliberately in the form scholars call a chiasmus. When a passage is chiastically structured, the first statement of the passage corresponds to the last one; the second statement corresponds to the second to last; the third to the third to last, and so on. The purpose of this careful design is to focus attention on the center of the passage, which provides the key to its interpretation. Without the disputed verses, the chiasmus is structured as follows:

Jesus (a) tells his disciples, “Pray lest you enter into temptation” (verse 40). He then (b) leaves them (verse 41a) and (c) kneels to pray (verse 41b). The center of the passage is (d), Jesus’ prayer itself, a prayer bracketed by his two requests that God’s will be done (verse 42). Jesus then (c′) rises from prayer (verse 45a), (b′) returns to his disciples (verse 45b), and (a′) finding them asleep, once again addresses them in the same words, telling them, “Pray lest you enter into temptation” (verses 45c–46).

The mere presence of this clear literary structure is not really the point. The point is how the chiasmus contributes to the meaning of the passage. The story begins and ends with the injunction to the disciples to pray so as to avoid entering into temptation. Prayer has long been recognized as an important theme in the Gospel of Luke (more so than in the other Gospels); here it comes into special prominence. For at the very center of this carefully constructed chiasmus is Jesus’ own prayer, a prayer that expresses his desire, bracketed by his greater desire that the Father’s will be done (verses 41c–42). The prayer at the center supplies the key to the passage’s interpretation. This is a lesson on the importance of prayer in the face of temptation. The disciples, despite Jesus’ repeated request to them to pray, fall asleep instead. Immediately the crowd comes to arrest Jesus. And what happens? The disciples, those who have failed to pray, “enter into temptation”; Jesus is left alone to his fate. What about Jesus, the one who has prayed? When the crowd arrives, he calmly submits to his Father’s will, yielding himself up to the martyrdom that has been prepared for him. Luke is trying to show that only prayer can prepare one to die.

What happens, though, when the disputed verses (verses 43–44) are injected into the passage? The center of the passage, and hence its focus, shifts to Jesus’ agony, an agony so terrible as to require a supernatural comforter for strength to bear it. It is significant that in this longer version of the story, Jesus’ prayer does not produce the calm assurance that he exudes throughout the rest of the account; indeed, after he prays “yet more fervently,” his sweat takes on the appearance of great drops of blood falling to the ground. My point is not simply that a nice literary structure has been lost, but that the entire focus of attention shifts to Jesus in deep and heartrending agony and in need of miraculous intervention.

This may not seem like an insurmountable problem until one realizes that nowhere else in Luke’s gospel is Jesus portrayed in this way. Quite the contrary, Luke has gone to great lengths to counter the very view of Jesus that these verses embrace. Rather than entering his passion with fear and trembling, in anguish over his coming fate, the Jesus of Luke goes to his death calm and in control, confident of his Father’s will until the very end.

That Luke deliberately portrayed Jesus this way becomes clear through a simple comparison with Mark’s version of the story, which Luke used as a source. Luke has completely omitted Mark’s statement that Jesus “began to be distressed and agitated” (Mark 14:33), as well as Jesus’ own comment to his disciples, “My soul is deeply troubled, even unto death” (Mark 14:34). Rather than falling to the ground in anguish (Mark 14:35), Luke’s Jesus bows to his knees (Luke 22:41). In Luke, Jesus does not ask that the hour might pass from him (cf. Mark 14:35); and rather than praying three times for the cup to be removed (Mark 14:36, 39, 41), he asks only once (Luke 22:42), prefacing his prayer, only in Luke, with the important condition, “If it be your will.”

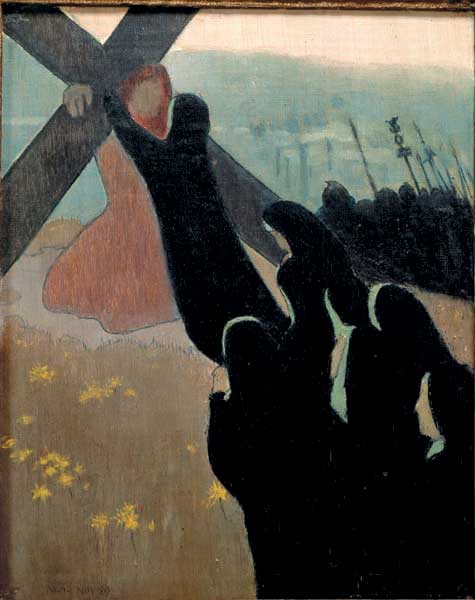

Luke also remodeled Mark’s account of the crucifixion to show that Jesus was calm and in control. Mark portrays Jesus as silent on his path to Golgotha. His disciples have fled; even the faithful women look on only “from a distance.” All those present deride him—passersby, Jewish leaders and the two robbers who are to be crucified with him. Mark’s Jesus has been beaten, mocked, deserted and forsaken, not just by his followers but finally by God himself. His only words in the entire proceeding come at the very end, when he cries aloud, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani” (My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?). He then utters a loud cry and dies.

In Luke’s account, Jesus is far from silent, and when he speaks, he shows that he is still in control, trustful of God his Father, confident of his fate, concerned for the fate of others. En route to his crucifixion, according to Luke, when Jesus sees a group of women bewailing his misfortune, he tells them not to weep for him, but for themselves and their children, because of the disaster that is soon to befall them (Luke 23:27–31). While being nailed to the cross, rather than being silent, he prays to God, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). On the cross, in the throes of his passion, Jesus engages in an intelligent conversation with one of the robbers who is crucified beside him, assuring him that they will be together that very day in paradise (Luke 23:43). Most telling of all, rather than uttering his pathetic cry of dereliction at the end, Luke’s Jesus, in full confidence of his standing before God, commends his soul to his loving Father: “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit” (Luke 23:46).

Luke thus made fundamental changes in his source (Mark) that are key to understanding our textual problem. At no point in Luke’s Passion narrative does Jesus lose control; never is he in deep and debilitating anguish over his fate. He is in charge of his own destiny, knowing what he must do and what will happen to him once he does it. This is a man who is at peace with himself and tranquil in the face of death.

The only anomaly in Luke’s portrayal of Jesus is the account of Jesus’ “bloody sweat,” an account absent from our earliest and best witnesses. Only here does Jesus agonize over his coming fate; only here does he appear out of control, unable to bear the burden of his destiny. Why would Luke have totally eliminated all remnants of Jesus’ agony elsewhere if he meant to emphasize it in yet stronger terms here? Why remove compatible material from his source, both before and after the verses in question? It appears that the account of Jesus’ “bloody sweat” is not original to Luke but is a scribal addition to the gospel.

Why, then, did scribes add these verses to the account? In the first example we discussed, from Mark 1, we saw scribes trying to make sense of a difficult passage. Like many modern readers, they were confused or perhaps even troubled by Mark’s description of Jesus’ display of anger toward the leper, and so they changed the text. In this second passage, we see the scribes altering the text to support their theological viewpoint.

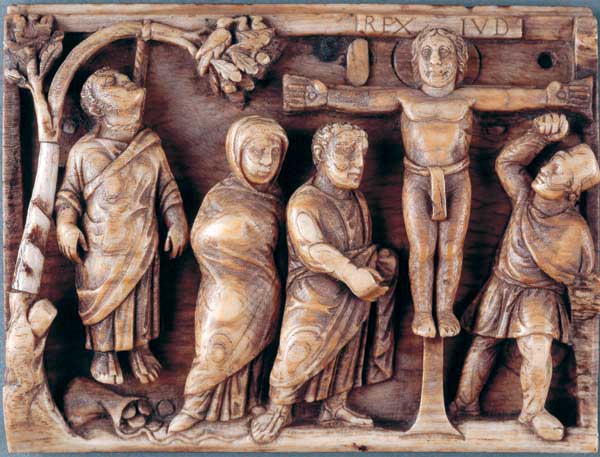

One of the most significant disputes during the second and third centuries involved the nature of Christ. Was he human? Was he divine? Was he both? If he was both, was he two separate beings, one divine and one human? Or was he one being who was simultaneously human and divine? These questions were eventually resolved in the creeds that are handed down even today, creeds that insist that there is “one Lord Jesus Christ” who is both fully God and fully man. Before these determinations were made, however, there were widespread disagreements.7 My contention is that Luke 22 was modified in order to stress the view that Jesus was fully human as well as divine.

The “bloody sweat” verses are alluded to three times by proto-orthodox authors of the mid- to late-second century (Justin Martyr, Irenaeus of Gaul and Hippolytus of Rome). Even more intriguing, each time these verses are mentioned it is in order to demonstrate that Jesus was truly a human being (as well as divine). The deep anguish that Jesus experienced according to these verses showed that he really was human, that he really could suffer like the rest of us. Thus, for example, the early Christian apologist Justin, after observing that Jesus’ “sweat fell down like drops of blood while he was praying,” claims that this showed “that the father wished his Son really to undergo such sufferings for our sakes,” so that we “may not say that he, being the Son of God did not feel what was happening to him and inflicted on him.”8 Justin and his proto-orthodox colleagues understood that the verses showed in graphic form that Jesus did not merely “appear” to be human: He really was human, in every way. It seems likely, then, that since, as we have seen, these verses were not originally part of the Gospel of Luke, they were added because they portrayed so well the genuine humanity of Jesus.

For proto-orthodox Christians like the scribes who amended this text, it was important to emphasize that Christ was a real man of flesh and blood because it was precisely the sacrifice of his flesh and the shedding of his blood that brought salvation—not in appearance but in reality.

Was Jesus an angry man? Yes, according to what I believe is the oldest form of Mark. Did he agonize in the face of death? Yes, says Mark. Never, says Luke. As we get closer to the original gospel texts, ever sharper (and sometimes increasingly different) portraits of Jesus begin to emerge.

The task of a New Testament textual critic is to try to recover the oldest, most original form of the text. For we can’t say what the words mean, if we don’t know what the words were.

This article is based on Bart D. Ehrman’s new book, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005).

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Kenneth V. Mull and Carolyn Sandquist Mull, “Biblical Leprosy—Is It Really?” BR 08:02.

Endnotes

See Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effects of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1993).

For an argument that there is no evidence of scriptoria in the earlier centuries, see Kim Haines-Eitzen, Guardians of Letters: Literacy, Power, and the Transmitters of Early Christian Literature (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 83–91.

See Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004), chapter 6.

On only two other occasions in Mark’s gospel is Jesus explicitly described as compassionate: in Mark 6:34, at the feeding of the five thousand, and in Mark 8:2, at the feeding of the four thousand. Luke tells the first story completely differently, and he does not include the second. Matthew, however, has both stories and retains Mark’s description of Jesus’ being compassionate on both occasions (Matthew 14:14 [and 9:30], 15:32). On three additional occasions in Matthew, and yet one other occasion in Luke, Jesus is explicitly described as compassionate, with this term (SPLANGNIZO) used. It is difficult to imagine, then, why they both independently of each other would have omitted the term from the account we are discussing if they had found it in Mark.

For these various interpretations, see Ehrman, “A Sinner in the Hands of an Angry Jesus,” in New Testmanet Greek and Exegesis: Essays in Honor of Gerald F. Hawthorne, ed. Amy M. Donaldson and Timothy Sailors (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003).

For a fuller discussion of this variant, see Ehrman, Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, pp. 187–194. My first treatment of this passage was cowritten with Mark Plunkett.