That Jesus spoke Aramaic there is no doubt.

By Jesus’ time numerous local dialects of Aramaic had emerged. Jesus, like other Palestinian Jews, would have spoken a local form of Middle Aramaic1 called Palestinian Aramaic. Palestinian Aramaic developed along with Nabatean Aramaic (in the area around Petra in modern Jordan), Palmyrene Aramaic (in central Syria), Hatran Aramaic (in the eastern part of Syria and Iraq) and early Syriac (in northern Syria and southern Turkey). Together, these five dialects make up Middle Aramaic.

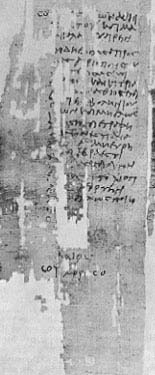

Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (beginning in 1947), Palestinian Aramaic was attested in only a few paltry inscriptions, on tombstones and on ossuaries (bone boxes). But with the discovery of those scrolls, more than a score of fragmentary texts written in Palestinian Aramaic came to light, giving us for the first time a corpus of literary texts from which we can learn something about the form of Aramaic spoken by Palestinian Jews in the centuries prior to Jesus and contemporaneously with him.2

Though Aramaic was the dominant language, it was not the only language spoken in Palestine at that time. The Dead Sea Scrolls reveal that a bilingualism existed in Palestine in the first and second century of the Christian era.3 In addition to Aramaic, some Jews also spoke Hebrew or Greek—or both.4 Different levels of Jewish society, different kinds of religious training and other factors may have determined who spoke what.

Hebrew was used in the sectarian literature of the Essenes, those Jews who settled at Qumran adjacent to the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. They apparently wanted to restore to primary usage what had come to be known as “the sacred language,” because it was the language of the Torah. During the Babylonian captivity (sixth century B.C.) many Jews had been cut off from their homeland; in Babylonia, they had come to use the dominant lingua franca, Aramaic, a sister language of Hebrew. After their return, some of the returnees probably used Hebrew, but the use of Hebrew does not seem to have been widespread.5 Groups like the Essenes, however, seem to have tried to resurrect the use of “the sacred language.” Hebrew would, of course, have continued in use in the Temple and in the emerging synagogues; the Law and the Prophets (the Torah and the Nevi’im) were read in Hebrew. But the majority of the people apparently no longer understood Hebrew, as we know from the custom that gradually developed of having an Aramaic translation of the scriptural reading given after the reading in Hebrew. This translation into Aramaic was done orally by a person called the meturgeman, the “translator.” In time such translations into Aramaic were written down. They are called targumim (singular, targum). Three examples of early targumim were discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.6

Greek, of course, was in widespread use in the Roman empire at this time. Even the Romans spoke Greek,7 as inscriptions in Rome and elsewhere attest. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Greek was also in common use among the Jews of Palestine.a The Hellenization of Palestine began even before the fourth-century B.C. conquest by Alexander the Great.8 Hellenistic culture among the Jews of Palestine spread more quickly after Alexander’s conquest, especially when the country was ruled by the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV Epiphanes (second century B.C.), and later under certain Jewish Hasmonean and Herodian kings.

The earliest Greek text found in Palestine is the bilingual Edomite-Greek ostracon dated to the sixth year of Ptolemy II Philadephus (277 B.C.).9 The Greek names of three musical instruments are recorded in an Aramaicized form in Daniel 3:5, probably imported along with the instruments themselves. But the instances of Greek words that have turned up in Aramaic documents of the first or second century A.D. can almost be counted on the fingers of one hand.10 Oddly enough, it is in the rabbinic writings of the third and fourth centuries A.D. where we find widespread use of Greek words in Aramaic or Hebrew texts; by that time Greek had made heavy inroads into the Semitic languages of Palestine.11

A host of early Jewish littérateurs, however, chiefly historians and poets, wrote in Greek.12 The most important Palestinian Jews in this group were Flavius Josephus (37/38–100 A.D.) and Justus of Tiberias. The latter was Josephus’ bitter opponent during the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 A.D.). Justus had received a thorough Hellenistic education, and after the revolt he wrote his “History of the Jewish War against Vespasian.”13 Josephus composed his own Jewish War to counteract the version of Justus.

Josephus comments on his own knowledge of Greek at the end of his Antiquities of the Jews:

“My compatriots admit that in our Jewish learning I far excel them. But I labored hard to steep myself in Greek prose [and poetic learning], after having gained a knowledge of Greek grammar; but the constant use of my native tongue hindered my achieving precision in pronunciation. For our people do not welcome those who have mastered the speech of many nations or adorn their style with smoothness of diction, because they consider that such skill is not only common to ordinary freedmen, but that even slaves acquire it, if they so choose. Rather, they give credit for wisdom to those who acquire an exact knowledge of the Law and can interpret Holy Scriptures. Consequently, though many have laboriously undertaken this study, scarcely two or three have succeeded (in it) and reaped the fruit of their labors.”14

Josephus thus gives the impression that few Palestinian Jews of his day could speak Greek well. That does not mean, however, that they could not carry on an ordinary conversation in perhaps a broken form of Greek.

Josephus mentions that he acted as an interpreter for the Roman general Titus, who spoke to the Jewish populace toward the end of the war.15 Josephus also tells us that he composed his Jewish War “in his native tongue.”16 This must mean Aramaic, although no copies have survived in this language. Subsequently he translated this history into Greek17 to provide people of the Roman empire with a record of the Jewish revolt. This was not easy for him, and he used “some assistants for the sake of the Greek.”18 He tells how he still looked on Greek as “foreign and unfamiliar.”19

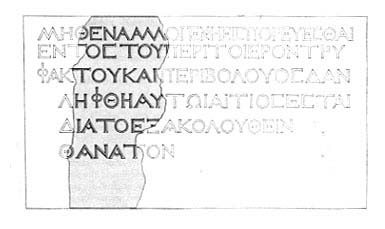

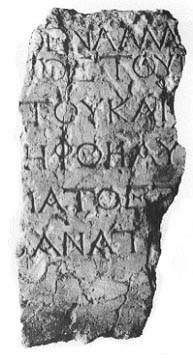

Other evidence of the use of Greek in Palestine includes inscriptions. A good number of these indicate that Greek was used for public announcements. Others found on ossuaries—inscribed in Greek and Hebrew (or Aramaic), or in Greek alone20—from the vicinity of Jerusalem21 testify to the widespread use of Greek among first-century Palestinian Jews at all levels of society.22

The Romans destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple in 70 A.D. Despite their defeat, the Jews again revolted against Rome in 132 A.D.—the Second Jewish Revolt, also called the Bar-Kokhba revolt after its military leader. By 135 A.D., they were again defeated, ending Jewish nationhood for nearly 2,000 years. From the period between the two revolts, numerous papyri written in Greek have come to light: letters, marriage contracts, legal documents, literary texts and some in a Greek shorthand (not yet deciphered).23 Among these texts are even some letters from the leader of the Second Jewish Revolt, Bar-Kokhba himself—written to his lieutenants, surprisingly enough, in Greek.24 One is remarkable, because it bears the name Soumaios, which the editor, Baruch Lifshitz, thinks is a way of writing in Greek the name of S

In Acts 6:1, early Jewish Christians of Jerusalem are spoken of as Hebraioi and Helle

Did Jesus himself speak Greek?

The answer is almost certainly yes. The more difficult question, however, is whether he taught in Greek. Are any of the sayings of Jesus that are preserved for us only in Greek nevertheless in the original language in which he uttered them?

That Aramaic was the language Jesus normally used for both conversation and teaching seems clear. Most New Testament scholars would agree with this.27 But did he also speak Greek? The evidence already recounted for the use of Greek in first-century Palestine provides the background for an answer to this question. But there are more specific indications in the Gospels themselves.

All four Gospels depict Jesus conversing with Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea, at the time of his trial (Mark 15:2–5; Matthew 27:11–14; Luke 23:3; John 18:33–38). Even if we allow for obvious literary embellishment of these accounts, there can be little doubt that Jesus and Pilate did engage in some kind of conversation (compare the independent testimony in 1 Timothy 6:13, which speaks of Jesus’ “testimony” before Pilate). In what language did Jesus and Pilate converse? There is no mention of an interpreter. Since there is little likelihood that Pilate, a Roman, would have been able to speak either Aramaic or Hebrew, the obvious answer is that Jesus spoke Greek at his trial before Pilate.

The same might be suggested by Jesus’ encounter with the centurion (Matthew 8:5–13; Luke 7:2–10; John 4:46–53). Luke gives him the title hekatontarchos, which might well indicate that he was a Roman centurion, or at least in charge of a troop of Roman mercenaries in the service of Herod Antipas (perhaps that is why he is called basiliskos, “royal official,” in John 4:46). In any event, Luke 7:9 implies he is a gentile. In what language did Jesus speak to this first gentile convert? Most probably in Greek.

In Mark 7:25–30 Jesus, having journeyed to the pagan area of Tyre and Sidon, converses with a Syro-Phoenician woman. Though the indigenous population of that area undoubtedly spoke some Semitic language, either Phoenician or Aramaic (sister languages), the Marcan account goes out of its way to identify the woman as Helle

Moreover, if there is any historicity to the incident in John 12:20–22 where “Greeks” (Helle

Such hints in these stories about Jesus’ ministry suggest that he did on occasion speak Greek.

Moreover, these specific instances in which Jesus apparently spoke Greek are consistent with his Galilean background. In Matthew 4:15, this area is referred to as “Galilee of the gentiles.”28 Growing up and living in this area, Jesus would have had to speak some Greek. Nazareth was a mere hour’s walk to Sepphorisb and in the vicinity of other cities of the Decapolis. Tiberias, on the Sea of Galilee, was built by Herod Antipas; the population there, too, was far more bilingual than in Jerusalem.29

Coming from such an area, Jesus would no doubt have shared this double linguistic heritage. Reared in an area where many inhabitants were Greek-speaking gentiles, Jesus, the “carpenter” (

The more difficult question is whether Jesus at times taught the people in Greek.

This question is especially important because, if the answer is yes, this opens the possibility that, in the words of A. W. Argyle, “We may have direct access to the original utterances of our Lord and not only to a translation of them.”31

Although Jesus probably did speak at least some Greek, it is unlikely that any of his preserved teaching has come down to us directly in that language.

Those who argue otherwise often begin by pointing out that no Christian documents are extant in Aramaic. Papias, a second-century bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor, maintained that Matthew had put together the logia, “sayings,” of Jesus “in the Hebrew dialect” (= Aramaic),32 but no one has ever seen them. More important, all four Gospels were composed in eastern Mediterranean areas outside of Palestine. That is why they are in Greek; they are the immediate products of a non-Palestinian Christian tradition, which has, however, many marks of its Palestinian, Semitic (especially Aramaic) roots.

Another point sometimes made by those who contend that Jesus taught in Greek is that a number of Jesus’ disciples had Greek names: Andrew, Philip and even Simon (a Grecized form of Hebrew S

No little part of the problem in maintaining that Jesus’ utterances, preserved for us in the Greek Gospels, are in the language in which he uttered them is that they are not in word-for-word agreement in the Gospels themselves. How then are we to determine which form is original? Did Jesus recite the Our Father prayer with five petitions, as It is preserved in Luke 11:2–4, or with seven petitions, as it is preserved in Matthew 6:9–13? One could naively maintain that he uttered it both ways. But is such a solution, which is always possible, really convincing? The same would have to be said about the different forms of the words of eucharistic institution (Mark 14:22–24; Matthew 26:26–28; Luke 22:17–20). In all three Gospels, Jesus says of the bread that this is his body, but the words are not the same. In Matthew, he says, “Take, eat; this is my body”; in Mark, “Take; this is my body”; in Luke, simply, “This is my body.” In Matthew and Mark, Jesus tells those at the Last Supper to drink of the wine, which is his blood, but the precise words are different. If these utterances of Jesus were preserved in the original language, the first problem would be to decide which of the Greek forms of the sayings were original.

Some scholars have attempted to analyze some of the Greek words in which the sayings of Jesus have been preserved to show that this was indeed their original language. For example, the word

Moreover, the word

A trenchant analysis by G. H. R. Horsley has convincingly shown that the Greek of the Gospels is not “Jewish Greek”;37 and yet it is Semitized enough to reflect a Palestinian matrix of the tradition that it enshrines.38 But there is no real evidence that it enshrines any didactic utterances of Jesus that he addressed to the crowds or to his followers in Greek. As Barnabas Lindars has remarked, “Careful analysis of the sayings shows again and again that the hypothesis of an Aramaic original leads to the most convincing and illuminating results.”39

Just as some scholars have attempted to show that some of Jesus’ teachings were uttered in Greek, others have tried to show—equally unconvincingly—that beneath his utterances is a Hebrew Vorlage (source).40 That Jesus at times used Hebrew is suggested by the Lucan version of his visit to the synagogue in Nazareth (Luke 4:16–19), where he is portrayed opening a scroll of Isaiah and finding a certain passage (Isaiah 61:1–2) and reading it. If that detail is considered historical, and not merely part of Luke’s programmatic scene, then Jesus would have read Isaiah in Hebrew.41 There is no mention of an Aramaic targum in this passage. So Jesus may be an example of a trilingual Palestinian Jew, capable of reading at least some Hebrew and of speaking some Greek, who normally used Aramaic as his dominant language.

It is important to keep in mind the three stages of the Gospel tradition. Stage I consists of what Jesus of Nazareth said and did during the approximate period between 1 and 33 A.D.; stage II consists of what the disciples and apostles taught and preached about him and his words and his deeds during the approximate period between 33 and 66 A.D. Stage III consists of what the evangelists sifted from that preaching and teaching and then redacted, each in his own way and each with his own evangelical purpose and literary and rhetorical style. This last stage occurred sometime between about 66 and 95 A.D. The canonical Gospels reflect stage III of the gospel tradition much more than stage I.

If we fail to keep this in mind, we fall into the danger of fundamentalism, of equating the Greek of stage III of the gospel tradition with its Aramaic stage I.

In short, what has come down to us about Jesus’ words and deeds comes in a Christian tradition that is in Greek. But Greek was not the form in which that tradition was originally conceived or formulated. None of the Gospels even purports to be a stenographic report or cinematographic reproduction of the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. The only thing that we are told that Jesus himself wrote, he wrote on the ground John 8:6–8)—and the evangelist took no pains to record it.

So the answer to the question, “Did Jesus speak Greek?” is yes, on some occasions, but we have no real record of it. Did Jesus teach and preach in Greek? That is unlikely; but if he did, there is no way to sort out what he might have taught in Greek from what we have inherited in the Greek tradition of the Gospels.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

See Pieter W. van der Horst, “Jewish Funerary Inscriptions,” in this issue.

See Richard A. Batey, “Sepphoris—An Urban Portrait of Jesus,” BAR 18:03.

Endnotes

See Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Phases of the Aramaic Language,” in A Wandering Aramean: Collected Aramaic Essays, Society of Biblical Literature Monograph Series 25 (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1979), pp. 57–84.

See Fitzmyer and Daniel J. Harrington, A Manual of Palestinian Aramaic Texts (Second Century B.C.–Second Century A.D.), Biblica et orientalia 34 (Rome: Biblica Institute, 1978).

See Fitzmyer, “The Languages of Palestine in the First Century A.D.,” in Fitzmyer, Wandering Aramean, pp. 29–56. Cf. Jonas C. Greenfield, “The Languages of Palestine, 200 B.C.E.–200 C.E.,” in Jewish Languages: Theme and Variations: Proceedings of Regional Conferences of the Association for Jewish Studies Held at the University of Michigan and New York University in March–April 1975, ed. H.H. Paper (Cambridge, MA: Assn. for Jewish Studies, 1978), pp. 143–154; J.M. Grintz, “Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language in the Last Days of the Second Temple,” Journal of Biblical Literature (JBL) 79 (1960), pp. 32–47; Robert H. Gundry, “The Language Milieu of First-Century Palestine: Its Bearing on the Authenticity of the Gospel Tradition,” JBL 83 (1964), pp. 404–408; Shmuel Safrai, “Spoken Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 4 (1991), pp. 3–8, 13.

Since Palestine was under Roman domination after the conquest of Pompey in 63 B.C., Latin was also used at times, as inscriptions in that language that have been discovered show. However, Latin seems to have been confined more or less to official use by Romans and for Romans or other visitors from the Roman empire. See further Fitzmyer, Wandering Aramean, pp. 30–32.

On triglossia, see J.T. Milik, Ten Years of Discovery in the Wilderness of Judaea, Studies in Biblical Theology 26 (London: SCM, 1959), pp. 130–133. Whether, however, Hebrew in a form approaching Mishnaic Hebrew “was the normal language of the Judaean population in the Roman period,” as Milik claims may be questioned. Cf. Pinchas Lapide, “Insights from Qumran into the Languages of Jesus,” Revue de Qumran (1972–1975), pp. 483–501.

Grintz (“Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language”) tries to argue that it was, but neither his arguments nor his evidence are rigorous enough to establish his point. Cf. John A. Emerton, “The Problem of Vernacular Hebrew in the First Century A.D. and the Language of Jesus,” Journal of Theological Studies 24 (1973), pp. 1–23.

The targum of Job from Qumran Cave 11 (J.P.M. van der Ploeg and A.S. van der Woude, Le targum de Job de la grotte xi de Qumran [Leiden: Brill, 1971]); the targumim of Leviticus and Job from Qumran Cave 4 (Milik, Qumran Grotte 411:1. Archéologie; II, Tefillin, mezuzot et targums [4Q128—4Q157]), Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 6 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1977), pp. 86–90.

See J. Kaimio, The Romans and the Greek Language, Commentationes humanarum litterarum 64 (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 1979).

See Martin Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in Their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974). For a later period, see Baruch Lifshitz, “L’Hellenisation des juifs de Palestine: A propos des inscriptions de Besara (Beth Shearim),” Revue biblique 72 (1965), pp. 520–538; “Du nouveau sur l’hellenisation des Juifs en Palestine,” Euphrosyne, new series 4 (1970), pp. 113–133.

Discovered at Khirbet el-Kom in 1971. See Lawrence T. Geraty, “The Khirbet el-Kom Bilingual Ostracon,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 220 (1975), pp. 55–61.

Four examples can be found in Fitzmyer, Wandering Aramean, p. 41. Some others could now be added to that list. Cf. A.W. Argyle, “Greek among the Jews of Palestine in New Testament Times,” New Testament Studies (NTS) 20 (1973–1974), pp. 87–89.

See Saul Lieberman, Hellenism in Jewish Palestine: Studies in the Literary Transmission, Belief and Manners of Palestine in the I Century B.C.E.–IV Century C.E., Texts and Studies of JTSA 18 (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1950; 2nd ed., 1962); “How Much Greek in Jewish Palestine?” in Biblical and Other Studies, ed. A. Altmann (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1963), pp. 121–141; Greek in Jewish Palestine: Studies in the Life and Manners of Jewish Palestine in the II–IV Centuries C.E., 2nd ed. (New York: Feldheim, 1965).

A list of them can be found in Carsten Colpe, “Judisch-hellenistische Literatur,” Der Kleine Pauly: Lexikon der Antike 2 (Stuttgart: Druckenmiller) (1967), pp. 1507–1512; cf. Carl R. Holladay, Fragments from Hellenistic Jewish Authors: Volume 1: Historians, Society of Biblical Literature Texts and Translations (SBLTT) 20, Pseudepigrapha Series (PS) 10 (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1983); Volume II: Poets (SBLTT 30, PS 12 [Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989]). Not all these Jewish authors, however, lived in Palestine.

Some of these are found in Fitzmyer and Harrington, Manual of Palestinian Aramaic Texts, others in Jean-Baptiste Frey, Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaicarum, 2 vols. (Vatican City: Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1950–1952), vol. 2, § 882–883, 887–891, 899–961, 964–970, 972, 983–986, 991–1000. Cf. Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum vol. 6, § 849; vol. 8, § 179–186, 197, 201, 208–209, 221, 224; vol. 17, § 784; vol. 19, § 922; vol. 20, § 483–492; L.H. Kant, “Jewish Inscriptions in Greek and Latin,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt II. 20/2 (1987), pp. 671–713.

See H. J. Leon, The Jews of Ancient Rome (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1960), pp. 75. Cf. Henri Leclercq, “Note sur le grec neotestamentaire et la position du grec en Palestine au premier siecle,” Les Etudes Classiques 42 (1974), pp. 243–255; Gerard Mussies, “Greek as the Vehicle of Early Christianity” NTS 29 (1983), pp. 356–369; “Greek in Palestine and the Diaspora,” in The Jewish People in the First Century; Historical Geography, Political History, Social, Cultural and Religious Life and Institutions, ed. S. Safrai and M. Stern, Compendia rerum iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 1–2 (Assert, Neth.: Van Gorcum; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1976), pp. 1040–1064.

Eric M. Meyers and James F. Strange (Archaeology, the Rabbis & Early Christianity [Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1981], pp. 62–91) go so far as to say, “It appears that sometime during the first century BCE Aramaic and Greek changed places as Greek spread into the countryside and as knowledge of Aramaic declined among the educated and among urban dwellers … Aramaic never died, though it suffered a strong eclipse in favor of Greek.” This eclipse was not characteristic, however, of the first century A.D.

See Pierre Benoit et al., Les grottes de Murabba‘at, Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 2 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961), § 89–107, 108–112, 114–116, 164; cf A.R.C. Leaney, “Greek Manuscripts from the Judaean Desert,” in Studies in New Testament Language and Text: Essays in Honour of George D. Kilpatrick on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday, ed. J.K. Elliott, Novum Testamentum Supplement (NovTSup) 44 (Leiden; Brill, 1976), pp. 283–300.

See Lifshitz, “Papyrus grecs du desert de Juda,” Aegyptus 42 (1962), pp. 240–256 (+ 2 pls.); Yigael Yadin, “New Discoveries in the Judaean Desert,” Biblical Archaeologist 24 (1961), pp. 34–50; “More on the Letters of Bar Kochba,” ibid., pp. 86–95. See also Naphtali Lewis, The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters: Greek Papyri, Judean Desert Studies (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1989).

C.F.D. Moule, “Once More, Who Were the Hellenists?” Expository Times (ExpTim) 70 (1958–1959), pp. 100–102. Cf. J.N. Sevenster, Do You Know Greek? How Much Greek Could the First Jewish Christians Have Known? NovTSup 19 (Leiden: Brill, 1968), p. 37.

See W. Sanday, “The Language Spoken in Palestine at the Time of Our Lord,” Expositor 1/7 (1878), pp. 81–99; “Did Christ Speak Greek?—A Rejoinder,” Expositor 1/7 (1878), pp. 368–388; A. Meyer, Jesu Muttersprache: Das galiläische Aramäish in seiner Bedeutung für die Erklärung der Reden Jesu (Leipzig: Mohr [Siebeck], 1896); Gustaf Dalman, The Words of Jesus Considered in the Light of Post-biblical Jewish Writings and the Aramaic Language (Edinburgh: T & T. Clark, 1902); Jesus-Jeshua: Studies in the Gospels (London: SPCK, 1929; repr. New York: Ktav, 1971), p. 1037; Friedrich Schulthess, Das Problem der Sprache Jesu (Zurich: Schulthess, 1917); Charles C. Torrey, Our Translated Gospels (New York: Harper & Row, 1936); André Dupont-Sommer, Les Araméens (Paris: Maisonneuve, 1949) 99, Matthew Black, “The Recovery of the Language of Jesus,” NTS 3 (1956–57) 305–13; Aramaic Approach to the Gospels and Acts, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1967); A. Diez Macho, La lengua hablada por Jesucristo, 2nd ed., Maldonado 1 (Madrid: Fe católica, 1976); Paul Kahle, “Das zur Zeit Jesu gesprochene Aramaïsch: Erwiderung,” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft (ZNW) 51 (1960), p. 55; E.Y. Kutscher, “Das zur Zeit Jesu gesprochene Aramaisch,” ZNW 51 (1960), pp. 46–54; H. Ott, “Um die Muttersprache Jesu: Forschungen seit Gustaf Dalman,” Novum Testamentum (NovT) 9 (1967), pp. 1–25; J. Barr, “Which Language did Jesus Speak?—Some Remarks of a Semitist,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 53 (1970–71), pp. 9–29; Barnabas Lindars, “The Language in Which Jesus Taught,” Theology 86 (1983), pp. 363–365.

However, in Isaiah 9:1 the phrase (gelîl haggôyim) is used as a description of “the land west of the Jordan,” northern Galilee, inhabited by pagans even in the time of the eighth-century prophet. Whether that is a stringent argument for that area in first-century Palestine is not apparent. J.M. Ross, who maintains that Greek was widely used in lower Galilee, doubts that it was true of northern Galilee (Irish Biblical Studies 12 [1990], p. 42).

See Sean Freyne, Galilee from Alexander the Great to Hadrian 323 B.C.E. to 135 C.E..: A Study of Second Temple Judaism (Notre Dame, IN: Univ. Of Notre Dame; Wilmington, DE: Glazier, 1980), pp. 101–154.

See J.A.L. Lee, “Some Features of the Speech of Jesus in Mark’s Gospel,” NovT 27 (1985), pp. 1–36. The abundance of parataxis in this early Gospel is often invoked as evidence of the influence of Aramaic.

See my commentary, The Gospel According to Luke, Anchor Bible 28, 28a (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981, 1985), pp. 904–906.

G.H.R. Horsley, “The Fiction of ‘Jewish Greek,’” New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity, 5 vols. (North Ryde, N.S.W., Australia: Macquarie Univ., 1981–1989), 5.5–40. But that fiction is often repeated; e.g. Ben Zion Wacholder, Eupolemus: A Study of Judaeo-Greek Literature (Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College, 1974), p. 256: “In the Gospels Jesus speaks Judaeo-Greek.”

See Klaus Beyer, Semitische Syntax im Neuen Testament: Band I, Satzlehre Teil 1, 2nd ed., Studien zur Umwelt des Neuen Testaments (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968); A. Ceresa-Gastaldao, “Lingua greca e categoric semitiche del testo evangelico,” Storia e preistoria dei Vangeli (Genoa: Universita di Genova, Facolta di lettere, 1988), pp. 121–141; Elliott C. Maloney, Semitic Interference in Marcan Syntax, Society of Biblical Literature Dissertation Series 51 (Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1981).

See Harris Birkeland, The Language of Jesus, Avhandlinger utgitt av Det Norske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo II. Hist-Filos. Klasse 1954/1 (Oslo: Jacob Dybwad, 1954). Cf. Jean Carmignac, The Birth of the Synoptic Gospels (Chicago: Franciscan Herald, 1987); Claude Tresmontant, The Hebrew Christ: Language in the Age of the Gospels (Chicago: Franciscan Herald, 1989). These claims have been adequately refuted by Pierre Grelot, L’Origine des evangiles: Controverse avec J. Carmignac (Paris: Cerf, 1986).