028

In 1876, Heinrich Schliemann completed a season’s excavation at Mycenae, where his faith in Homer’s text was repaid with spectacular success. Having excavated one of the shafts in grave circle A, close by the Lion Gate, Schliemann had come down on a burial containing the remains of a man whose face in death had been covered by a gold plate, beaten out to form a crude portrait. According to a story widely told, Schliemann claimed that the features of the dead man’s face had remained visible for a split second before crumpling into dust. He cabled the king of Greece and announced that he had discovered the tomb of Agamemnon.

030

In recent years Schliemann’s record at Troy and Mycenae has come under scrutiny, and many of his claims have been shown to be exaggerated, perhaps even to the point of fabrication, but part of his legacy has been a popular and widespread belief that archaeology can affirm stories and historical traditions that otherwise exist only in literary form. Even if Schliemann were discredited utterly and we knew that he had planted the so-called Treasure of Priam, the Bronze Age jewelry that his wife Sophie was famously photographed wearing, we would still like to believe his excavations had proved that Homer’s account of the Trojan War was based on actual historical events. The tumulus containing the many city levels of Troy is vividly real in a way that Homer’s poetry is not. Words are ephemeral, but objects have a tangible reality that is hard to resist. When archaeology is applied to myth traditions like that of the Trojan War, it is hard not to connect the two and to treat the archaeology as a way of amassing evidence proving the myth.

Archaeologists often decry this approach. “Archaeology is archaeology is archaeology,” they proclaim. By this, they mean that archaeology is not the handmaiden of history and does not exist to generate data that proves historical or literary traditions. Archaeology is its own discipline, with its own story of the past to tell. Hissarlik, the mound of Troy, has exposed evidence of a Bronze Age culture (and later cultures as well), and these deserve to be studied on their own.

031

One can understand the frustration of the archaeologist whose work is hijacked in an attempt to prove Homer, but there is also a danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater if we insist on keeping the lines between disciplines entirely separate.

Perhaps what is needed is a different emphasis. After all, if Homer’s epic poetry purports to tell the story of a war set at Troy and if we have located a Bronze Age city in the place where he understood that war took place, it seems almost perverse to keep archaeology and epic poetry neatly compartmentalized from each other. Archaeology and epic may be taught in different university departments, but Homer’s audience lived in a world where there were abundant reminders of a golden age all around them: Mycenae’s Lion Gate was still there in the eighth century B.C. and in the fifth century B.C., too, the Age of Pericles. For them the past continued to affect the present, and their mythology was shaped by a dialogue between past and present.

Instead of combing archaeology for evidence to prove that epic is an accurate reflection of a historic society or, conversely, rejecting any connection between them, what we ought to do is ask if there are correspondences between archaeological materials and mythical traditions that would yield to us a richer understanding of both.

As an example of this, we might consider the case of Theseus, the great Athenian hero. Like many Greek heroes, he is born of two fathers: His divine father is Poseidon; his mortal father, Aegeus, king of Athens. Theseus is raised by his mother, Aethra, at Troizen and is unaware of his royal parentage. Upon reaching manhood Theseus learns his father’s identity after passing a test set for him by Aegeus: He successfully moves a rock covering a pair of sandals and a sword, tokens of his lineage left there by his father. Theseus travels with them to Athens to claim recognition from his father. On the way, he performs various great deeds that eventually will be commemorated in song and on vases. For example, he defeats Procrustes, the bandit who was in the habit of forcing his victims to fit into a bed of specific size. If they were too short, he stretched them on a rack, and if they were too tall, he lopped off any pieces that hung over the edges.

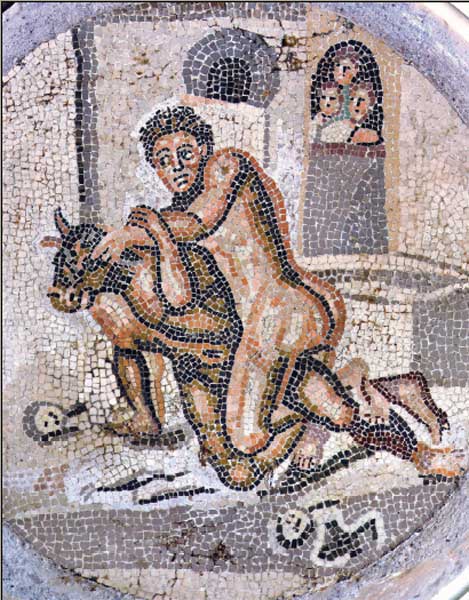

Once in Athens, again following the pattern of many hero-myths, Theseus performs deeds to benefit his people. Perhaps the best-remembered story about Theseus concerns his voyage to Crete. Crete was ruled by King Minos, who controlled a vast empire across the Aegean. His power, nevertheless, had not saved his family from disaster: After refusing to sacrifice a magnificent bull to the gods, he was punished for his impiety. His wife, Pasiphae, fell in love with the bull, mated with it and gave birth to a monster, half bull, half man: the Minotaur. This creature was kept in a labyrinth beneath the palace and fed on the flesh of young men and women who were sacrificed to it. The victims were tribute paid by Athens, which at that time was under the suzerainty of Minos.

032

When the time comes for the Athenians to choose the victims, Theseus offers himself voluntarily and assumes leadership of the expedition. Upon reaching Crete, Theseus meets Ariadne, daughter of Minos. She falls in love with Theseus and helps him to make his way in and out of the labyrinth by means of a thread tied to the lintel at the entrance to the maze. At the heart of the labyrinth Theseus finds the Minotaur asleep and manages to slay him, with his bare fists in some versions. Retracing his steps via the thread, he escapes and flees with Ariadne. On the pair’s arrival at Naxos, Dionysus sees Ariadne and, smitten with her beauty, carries her off. Because of his grief at losing her, Theseus sails on to Athens with a black sail on his ship instead of a white one, the signal intended to show that the Athenians have been successful and that the youths have been saved. Thinking that his son has perished in the labyrinth, Aegeus hurls himself down from the Acropolis and dies, giving his name to the Aegean Sea.

Is there any point at which this story can shed light on the history of the Bronze Age Aegean that has emerged over the last century?

To answer that question we must look at the archaeology of Crete. Since the late 19th century, when Sir Arthur Evans commenced excavations at Knossos, it has become clear that Crete was home to an extraordinary civilization in the second millennium B.C. Based on pottery sequences, archaeologists are now able to chart the growth of Minoan culture on Crete from a prepalatial period during the late third millennium B.C. to the period of greatest power and prosperity in the second half of the second millennium—the First Palatial period, which lasted from approximately 1900 to 1700 B.C., followed by the Second Palatial period, which ran from approximately 1700 to 1450 B.C. and even a third and final phase that centered on Knossos from perhaps 1450 to 1300 B.C. These absolute dates should be treated with caution, but the dates are not central to our story. The terminology, however, does alert us to two important features of Cretan society. We refer to the civilization of Bronze Age Crete as palatial because palaces were at the heart of all economic, political and religious life. The division into successive, discrete periods also serves to remind us that the palaces experienced fluctuating fortunes, at times enjoying enormous prosperity and at other times suffering destruction and abandonment.

The palaces were located around the coastline of Crete at Knossos, Mallia, Zakro, Phaistos and Khania. From here Minoan fleets put out to sea and engaged in trade or raiding throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Shipwrecks from the end of the Bronze Age, such as the Uluburun wreck excavated by George Bass off the coast of Turkey, revealed cargoes of glass ingots, tin, copper, Baltic amber, scarabs of lapis lazuli, and drinking cups. When we add perishable items such as perfumes, textiles, spices and slaves, all of which were certainly among the items circulating around the eastern Mediterranean, it comes as no surprise that the Minoans grew rich on their control of the trade routes that reached Egypt and Syria to the east and south and the Adriatic in the west.

On Crete itself, social organization appears to have been increasingly stratified. It is not difficult to imagine an elite of sophisticated consumers dominating life in the palaces, and, as with any complex society, the complement of this palatial ruling class was the large force of farmers and artisans who produced the food, the pottery, the exquisite jewelry and the artwork that the elite enjoyed. The exact nature of this social stratification and how it worked in practice remains somewhat opaque; for example, we don’t know if kings or queens, or both, sat on the throne. Were they high priests ruling on behalf of the gods or taken as incarnations of the gods? We simply don’t know.

We are also in the dark when it comes to the world of ideas and beliefs inhabited by the Minoans since we do not possess any Minoan literature. No 033hymns or prayers survive to reveal their religious system. Instead we have to rely on mute sources, such as the frescoes decorating their shrines and cult centers, as well as carved gemstones and seals that depict cultic activity. These suggest that the Minoans recognized a powerful goddess who is sometimes shown looming over lesser mortals. Also, many household shrines have revealed bell-shaped figurines showing goddesses, or perhaps the one goddess in various forms, in a characteristic pose with arms open and bent upwards at the elbow. Faience figurines of women wearing the characteristic Minoan flounced skirt with snakes wrapped around their arms may be depictions of goddesses or the priestesses who served them.

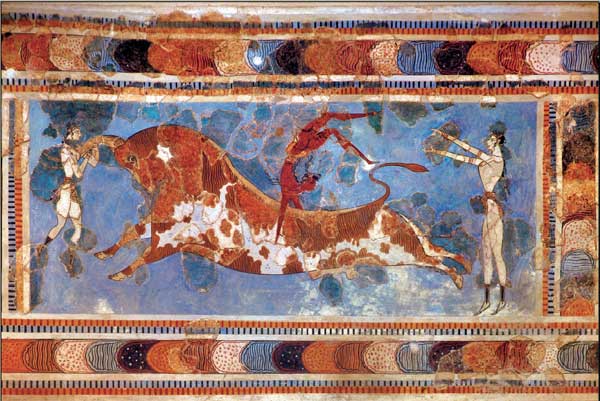

Another deity, or at least a divine principle, worshiped by the Minoans was the bull. Again, we rely on the evidence of frescoes and gems that show how the Minoans practiced an astonishing ritual that consisted of grasping a bull by its horns and leaping over its back. When we add to this the ubiquity of stylized bulls’ horns, so-called “horns of consecration,” as well as the bull’s-head rhyta (drinking vessels; singular, rhyton) and vivid portraits of individual beasts, there can be no doubt that the Minoans treated the bull with deep reverence. To them it was the embodiment of masculine power. The bull may well have represented the young male consort of the goddess of love, a pattern that recurs throughout the ancient near east from Tammuz and Ishtar to Venus and Adonis, although if this is the case we cannot even give names to the Cretan versions of this divine couple.

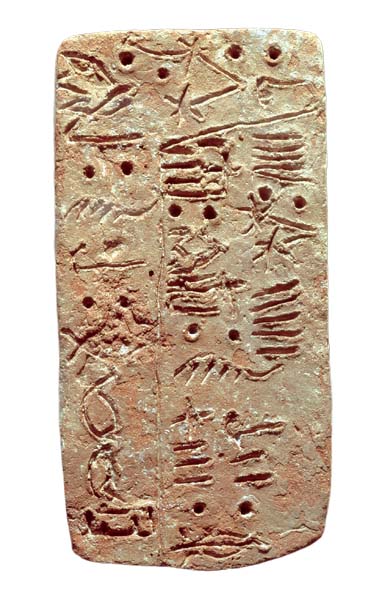

One other aspect of Minoan culture requires mention. The Minoans were literate, or more accurately, their society included a class of scribes who employed a script, Linear A, to record the goods placed in the great storage rooms of the palaces and to mark vessels and objects dedicated in their sanctuaries. Linear A has not been deciphered, but the presence of clay tablets inscribed with this script both on Crete and further afield fits with a general picture of expanding Cretan influence in the Second Palatial period. Some scholars have gone so far as to refer to the Minoization of the Aegean during the Late Bronze Age. Whether this resulted in political domination by Knossos or one of the other Cretan palaces cannot be proved. However, the growth of Cretan power is undeniable. Cretan looms and weights were adopted far abroad, and conical cups popular in Cretan rituals turn up in increasing numbers. Frescoes found on the island of Thera reflect such pervasive Minoan influence that some scholars have interpreted them as evidence for Thera’s origins as a Minoan colony. 034(Minoan frescoes have even been found in Israel and Egypt; see “Minoan Frescoes in Egypt, Turkey and Israel” sidebar.)

Linear A and its successor, Linear B, play an important part in our story. In the final phase of Knossos’s occupation, the writing used to record palace inventories was Linear B. Although some of the ideograms in this script are very close to Linear A, suggesting that the two are related as writing systems, Linear B has been successfully deciphered, unlike its predecessor. The language somewhat awkwardly rendered into the syllabary of Linear B is a form of Greek, while Linear A is not. It seems, then, that the occupants of Knossos in this Third Palatial period were Greek speakers and that they had replaced their Minoan predecessors in control of Cretan society and palatial culture. This shift can hardly signify anything less than an invasion of Minoan Crete from mainland Greece. (Linear B tablets have also turned up in great numbers at Pylos, 035Mycenae, Tiryns and most recently at Thebes.) This is not surprising. In fact, the takeover of the Minoan palaces by invaders from the mainland is the culmination of competition between mainland Mycenaean Greeks and the Minoans that had been brewing for two hundred years.

On mainland sites like Mycenae, the material record shows a taste for Minoan handicrafts in pottery shapes and decoration and in jewelry. The Mycenaean Greeks were in close contact with the Minoans, importing goods and perhaps even craftsmen from Crete. However, the relationship had not been entirely amicable. For all of the appeal of Minoan style to the Mycenaeans, there was genuine competition between them along the trade routes of the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. As the fortunes of the Minoans waned, measured by the shrinking amount of their pottery found beyond Crete, so, too, Mycenaean material increased in volume. It turns up further afield as well. Even if this evidence does not support the notion of a trade war, an anachronistic concept that implies too great a degree of central authority, coordination and organization, it is not too much to imagine the warlords of Mycenae increasingly turning their attention to Crete. The ruling elite of the Mycenaean world buried its leaders with their weapons, finely made blades inlaid with silver and enamel, and marked their graves with stelae adorned with chariots. This was a culture with a warrior ethos. At some point it would have dawned on one of these Mycenaean princes that the palaces of Crete, with all their wealth, were not protected by walls. It seems clear that it was Greeks who ruled at Knossos in its final phase and that the complex, hierarchical organization of palatial culture was brought back to the Greek mainland and applied to Mycenaean states such as Pylos, Mycenae and 037Thebes. By the end of the Bronze Age, Mycenae must have looked like a rougher version of its more sophisticated Cretan cousin at Knossos.

The final phase of both cultures occurred toward the end the 13th century B.C., when the complex social and economic systems of the Palatial period simply collapsed. No single factor explains this collapse. It remains somewhat of a mystery, but an explanation is not significant to our story.

The aftermath of this breakdown brings us back to Theseus. Here we have a hero whose cycle of stories touches upon all sorts of themes. There is the unknown young man who must prove his character is a match for the royal status he is destined to enjoy. There is the adventurer who travels to Hades and the king who saves his people and unites all of Attica. There is also the mainlander who travels to Crete to throw off the oppressive burden of Minoan control.

I am not suggesting that we read this as if the story corresponds strictly to historical events. The popularity of Theseus’s story for hundreds of years is not, in and of itself, sufficient to prove that there was ever an individual who single-handedly saved Athens from foreign domination, whether by Cretans or Amazons. Nevertheless, the preceding summary of Crete and mainland Greece in the second millennium shows that the myth and the story told by archaeology are not entirely divorced from each other. It is not going too far to suggest that the myth may contain a memory, the memory of a great and prosperous earlier age during which the mainland saw Crete as powerful and dominant.

To be sure, the story of Theseus and the Minotaur is hardly the equivalent of scientific archaeology with its ability to test the contents of Minoan storage vessels or to use ground-penetrating radar to find traces of the settlements that surrounded the palace at Knossos. Even so, telling a story set in a mysterious labyrinth, which surely corresponds 041to the many levels, corridors and staircases of Knossos, is, like archaeology, an interpretation of the past, anchored in a specific place and shaped by familiarity with it. Myth serves many functions, but one powerful impetus behind mythology is an overwhelming human drive to tell stories, to take dim memories, confused images, puzzling and half-understood reminders of the past and to put them into some kind of order. If archaeology is our way of understanding the past, mythology was the Greeks’ way of understanding theirs.

Stories have a beginning, middle and end. They repeat motifs, and they reassure us, the audience, by rendering the confusion and unpredictability of life into neat narrative patterns: the hero is set a task, goes on his quest, is victorious and restores order. To the Greeks, the story of Theseus was a cycle of myths that helped them deal with their own past, which was situated in actual places still visible in their landscape. The ancient Greeks could see, touch and feel Knossos and Mycenae. They wondered who had lived there. Were they their ancestors? Had they once ruled the seas?

So what does the story of Theseus on Crete say to the Greeks? It recognizes that Crete was home to a wealthy culture based on naval power. Thucydides, a sober historian who might have rejected these stories as fabrications, has this to say about Minoan sea power:

But as soon as Minos had formed his navy, communication by sea became easier, as he colonized most of the islands, and thus expelled the malefactors. The coast populations now began to apply themselves more closely to the acquisition of wealth, and their life became more settled; some even began to build themselves walls on the strength of their newly acquired riches.

(Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.8.2–3)

For the historian, then, there was no doubt that Crete had been the super-power of an earlier age. In the story of Theseus, poets and mythographers were forging a connection between Athens’s past and that superpower. Where history deals with places, events and processes, mythology could transform this into a story on a human scale: Theseus traveled to Crete. An Athenian prince slew the Minotaur. Does this recall a historic event in which the Mycenaeans forcefully overthrew their Minoan overlords?

Aside from explaining the past and linking it to the present, the story also served to stake a specifically 042Athenian claim to importance in the past, correlating to their status at the time when the stories gained popularity in the fifth century B.C. This was the age when Athens became a mighty naval power, its ships patrolling the Aegean and exacting tribute from its allies. In one sense, then, the story of Theseus resisting the impositions of Minos and his ghastly tribute is an inversion of Athens’s own imperial position. How reassuring, at a time when the Athenians in reality deliberated on the fate of subject peoples, on occasion voting to execute entire populations, that they should have a national myth involving a hero who liberated victims from unjust exactions. This is the kind of mythologizing designed to mask the abuse of power, by casting the powerful as morally superior.

We should not ignore the circumstances in which the story of Theseus became fixed in the imagination of the Athenians. In the period after the Persian Wars, democratic Athens was casting about for stories that glorified its own might; it was, after all, a city that had come to prominence in defending Greece from the Persians. Until now, Sparta had been seen as the unchallenged champion in the field of battle, but at Marathon in 490 B.C., the Athenians had acquitted themselves triumphantly, and at Salamis their navy and their tactics had made the difference between defeat and victory. It is telling, therefore, to find that the Athenian Treasury at Delphi should at this time have been decorated with two sets of metopes: one set commemorates the Dorian hero par excellence, Herakles, while the second set matches his labors with those of the younger, fresh-faced Ionian hero: Theseus. In this way the Athenians staked their claim: We have our (Athenian) hero, just as important and powerful as your (Spartan) hero.

On this reading, no Greek myth is ever likely to have only one meaning. Jungian archetypes arising from a collective unconscious may help us to recognize certain patterns in myth, but the key to myth is its flexibility. It can repeat age-old patterns but can also serve new and particular ends arising at specific times and under specific conditions. The Athenian hero Theseus provided the Athenians with a way of imagining how they fit into a world that included a glorious but distant past (Crete), foreign threats successfully defeated (Persians and Amazons) and fellow Greeks with whom they were in competition (Spartans and Herakles).

For those whose interests are focused on the Bible and Biblical archaeology, the example of Theseus may offer some food for thought. On the model I am suggesting here, it would be a dangerous enterprise to try to employ archaeology to prove the Bible in any literal way, since Biblical traditions and archaeology are fundamentally different kinds of narratives about the past. On the other hand, it is certainly worth trying to read the stories of the Bible with a view to understanding the time and setting in which those stories were generated. Take, for example, the strong bias in the Pentateuch toward desert nomadism. It is Cain, the farmer, whose offerings are not pleasing to the Lord, unlike Abel’s offering of the firstborn from his flock, which is pleasing in the eyes of the Lord. The herder’s sacrifice is preferable to the sedentary farmers. Babel, Sodom and Gomorrah are variations on a theme: the city and civilization are tied to corruption. In the desert lies purification. If Knossos was both a real place and the setting for Theseus’s killing of the Minotaur, then surely Babel is both Babylon and the symbol of human arrogance. “This is but the start of their undertakings,” observes Yahweh, upon seeing “the tower that the sons of man had built” (Genesis 11:5–6). In other words, we are in the fortunate position of having both concrete, or at least 043mud-brick, evidence for the world of the patriarchs, thanks to archaeology, and complementary evidence for the world of the imagination that they inhabited. In that world there was a Babylon, and it was evil.

In a similar way, the story of Exodus lends itself to a reading that moves beyond using archaeology to prove the Biblical narrative. Archaeology identifies a complex and magnificent civilization in second-millennium Egypt, but the stories of the enslavement of the Hebrews in Egypt, their flight from Egypt and the arrival in the Promised Land provide a much richer mytho-poetical viewpoint and a way for the Israelites to address their past (which may well have taken place in Egypt) and their special relationship with their God. As they pass through the desert, they are purified, given laws by Moses, the great culture hero of Israelite tradition, and reunited with God. Their arrival in Canaan puts an end to an exile that began with the expulsion from Eden. Instead of looking for literal confirmation of myth-history in archaeology, or vice versa, we read these narratives to understand the fears, anxieties, hopes and dreams that shaped the Hebrew Bible.

Mythological traditions do not lead us into the same world as archaeology does. The latter is our attempt to win back tangible evidence for the world as it was before us, so that we can reconstruct the look and shape of the past. But the past was inhabited by humans with passions, imagination, fears and prejudices. The avenue to that past, more often than not, passes through mythology.

In 876, Heinrich Schliemann completed a season’s excavation at Mycenae, where his faith in Homer’s text was repaid with spectacular success. Having excavated one of the shafts in grave circle A, close by the Lion Gate, Schliemann had come down on a burial containing the remains of a man whose face in death had been covered by a gold plate, beaten out to form a crude portrait. According to a story widely told, Schliemann claimed that the features of the dead man’s face had remained visible for a split second before crumpling into dust. He cabled the king of […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username