Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?

026

Since 1960, the Armenian, the Greek and the Latin religious communities that are responsible for the care of the Holy Sepulchre Church in Jerusalem have been engaged in a joint restoration project of one of the most fascinating and complex buildings in the world.

In connection with the restoration, they have undertaken extensive archaeological work in an effort to establish the history of the building and of the site on which it rests. Thirteen trenches were excavated primarily to check the stability of Crusader structures, but these trenches also constituted archaeological excavations. Stripping plaster from the 028walls revealed structures from earlier periods. A new, modern drainage system was put in place, but the work itself was also used for archaeological research. Elsewhere, soundings were made for purely archaeological purposes.

The results of all this excavation and research have now been published in a three-volume final report by Virgilio C. Corbo, professor of archaeology at the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum in Jerusalem.a Father Corbo has been intimately involved in this archaeological work for more than 20 years, and no one is better able to report on the results than he.b

Although the text itself (Volume I) is in Italian, there is a 16-page English summary by Stanislao Loffreda. Father Loffreda has also translated into English the captions to the archaeological drawings and reconstructions (Volume II) and the archaeological photographs (Volume III). So this handsome set will be accessible to the English-speaking world as well as to those who read Italian.

During the late Judean monarchy, beginning in about the seventh or eighth century B.C., the area where the Holy Sepulchre Church is now located was a large limestone quarry. The city itself lay to the southeast and expanded first westward and then northward only at a later date. The high quality, so-called meleke-type limestone has been found wherever the excavations in the church reached bedrock. Traces of the quarry have been 030found not only in the church area, but also in excavations conducted nearby in the 1960s and 1970s—by Kathleen Kenyon, in the Muristan enclave of the Christian Quarter, and by Ute Lux, in the nearby Church of the Redeemer. This meleke stone was chiseled out in squarish blocks for building purposes. The artificially shaped and cut rock surface that remains reveals to the archaeologist that the area was originally a quarry. Sometimes the workers left partially cut ashlars still attached to the bedrock (Corbo photo 62). In one area (east of St. Helena’s Chapel in the Holy Sepulchre Church), the quarry was over 40 feet deep. The earth and ash that filled the quarry contained Iron Age II pottery, from about the seventh century B.C.; so the quarry can be securely dated.1

According to Father Corbo, this quarry continued to be used until the first century B.C. At that time, the quarry was filled, and a layer of reddish-brown soil mixed with stone flakes from the ancient quarry was spread over it. The quarry became a garden or orchard, where cereals, fig trees, carob trees and olive trees grew. As evidence of the garden, Father Corbo relies on the fact that above the quarry he found the layer of arable soil.2 At this same time, the quarry-garden also became a cemetery. At least four tombs dating from this period have been found.

The first is the tomb traditionally known as the tomb of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea (No. 28 in Corbo’s list). The Gospel accounts (John 19:38–41; Luke 23:50–53; Matthew 27:51–61) report that Joseph took Jesus’ body down from the cross; Nicodemus brought myrrh and aloes and, together, he and Joseph wrapped Jesus’ body in linen and buried him in a garden in Joseph’s newly cut, rock-hewn tomb.

The tomb traditionally attributed to Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea is a typical kokh (plural, kokhim) of the first century. Kokhim are long, narrow recesses in a burial cave where either a coffin or the body of the deceased could be laid. Sometimes ossuaries (boxes of bones collected about a year after the original burial) were placed in kokhim.

In the course of restoration work in the Holy Sepulchre Church a hitherto unknown passage to this tomb was found beneath the rotunda.

Another type of tomb, known as an arcosolium (plural, arcosolia), was also common in this period. An arcosolium is a shallow, rock-hewn coffin cut lengthwise in the side of a burial cave. It has an arch-shaped top over the recess, from which its name is derived. The so-called tomb of Jesus (Nos. 1 and 2 in Corbo’s plates) is composed of an antechamber and a rock-cut arcosolium. Unfortunately, centuries of pilgrims have completely deformed this tomb 032by pecking and chipping away bits of rock as souvenirs or for their reliquaries. Today the tomb is completely covered with later masonry, but enough is known to date it as an arcosolium from about the turn of the era.

A third, much larger tomb, probably of the kokh type was found in front of the church (in the Parvis). This tomb was greatly enlarged in Constantine’s time and was used as a cistern. Very little remains of it, but Corbo’s study reveals its original function as a tomb.

Finally, although not mentioned by Corbo, in the late 19th century another tomb of the kokh type was found in the church area under the Coptic convent.3

Obviously many other tombs that existed in the area were destroyed by later structures. But the evidence seems clear that at the turn of the era, this area was a large burial ground.

The tomb in front of the Church was actually cut into the rock of what is traditionally regarded as the hill of Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified. It is possible that the rocky outcrop of Golgotha was a nefesh, or memorial monument.c However, this hypothesis needs more study before it can be advanced with any confidence.

The next period for which we have archaeological evidence in the Holy Sepulchre Church is from the period of the Roman emperor Hadrian. In 70 A.D. the Romans crushed the First Jewish Revolt; at that time they destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple. Less than 70 years later, in 132 A.D., the Jews again revolted, this time under the leadership of Rabbi Akivah and Bar Kokhba. It took the Romans three years to suppress the Second Jewish Revolt. This time, however, the victorious Roman emperor Hadrian banned Jews from Jerusalem and trenched around it a pomerium, a furrow plowed by the founder of a new city to mark its confines. To remove every trace of its Jewish past, Hadrian rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman city named Aelia Capitolina. (For the same reason, he also changed the name of the country from Judea to Palaestina or Palestine.)

On the site of the former seventh-century B.C. quarry and first-century B.C. orchard-garden and cemetery, where the Holy Sepulchre Church was to be built, Hadrian constructed a gigantic raised platform—that is, a nearly rectangular retaining wall filled with earth. On top of the platform, he built a smaller raised podium, and on top of the podium, he built a temple. Although the 033remains of the Hadrianic wall enclosing the platform are scant, its existence is clear.

Because the area had been dug as a quarry and because it had also been honeycombed with tombs and was left with depressions and protrusions of uncut rock, the building of this platform was necessary to create a level construction site.

Many of the ashlarsd used by Hadrian for the retaining wall of the platform were actually old Herodian ashlars—034left after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and Herod’s temple in 70 A.D. They are identical in size and facing to the Herodian ashlars in the retaining wall of the Temple Mount. Hadrian’s wall therefore looked like a Herodian wall—much like the famous Western Wall of the Temple Mount which is, even today, a focus of Jewish reverence.

Although not mentioned by Corbo, the upper part of Hadrian’s retaining wall even had slightly protruding pilasters or engaged pillars along the outer face of the upper part of the wall, thereby creating the appearance of regularly spaced recesses. The Hadrianic enclosure thus duplicated the Herodian Temple Mount enclosure, although unfortunately the latter did not survive to a height that included these pilasters, except in traces. This style can be seen, however, in the Herodian wall enclosing the traditional tomb of the patriarchs (the cave of Machpelah) at Hebron.e

The fact that Hadrian appears to have deliberately attempted to duplicate the Herodian enclosure at the Temple Mount has special significance. Instead of a temple to Yahweh, however, Hadrian built on his raised enclosure an elaborate temple to the goddess of love, Venus/Aphrodite.

Corbo refers to Hadrian’s temple as Capitolium, that is, dedicated to Jupiter the Capitoline. For this, he relies on the fifth-century testimony of Jerome who mentions a Jerusalem temple dedicated to Jupiter. However, Eusebius in the fourth century tells us Hadrian’s temple at this site was dedicated to Venus/Aphrodite. There is no reason for Corbo to choose Jupiter over Venus/Aphrodite, 035especially because Dio Cassio in the third century fixes the site of the temple of Jupiter on the site of the former Jewish Temple, that is, on the Temple Mount. That is the temple Jerome is referring to. A number of other ancient writers from the fifth century on refer to a temple of Venus/Aphrodite on the site where later the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built.

To support his attribution to Jupiter, Corbo claims to have found in the rotunda of the church two fragments from a triple cella that would have accommodated statues of the Capitoline triad, Venus, Minerva and Jupiter. There is no basis, however, for suggesting that these fragmentary remains are part of a triple cella—or even that they are part of the pagan temple itself. As so often in this report, Corbo’s assertion as to the date of walls is merely that—pure assertion. No evidence is given.

Parts of Hadrian’s enclosure wall have survived. According to Corbo, fragments of other walls, found in cisterns and in what was the first-century B.C. garden, belonged to the substructure of Hadrian’s temple. But for this, as before, we must rely solely on Corbo’s assertion. He presents no evidence on which his conclusions can be tested. In any event, nothing of the visible parts of Hadrian’s temple has been discovered. As we know from historical sources, it was razed to the ground by Constantine, so there is no hope of recovering it. Likewise, the small podium on which the temple sat, on top of the enclosure-platform; the podium too has vanished without a trace.

Corbo’s reconstruction of the Hadrianic temple is thus completely speculative—and unsatisfactory. In the first place, he assumes it was a three-niche structure pursuant to his mistaken theory that it was dedicated to Jupiter the Capitoline rather than Venus/Aphrodite.f But, in any event, there is no known parallel to Corbo’s plan.g

Queen Helena, Constantine’s mother, was shown the site on her visit to Jerusalem in 326 A.D. We do not know in what condition the site was at this time. Perhaps the pagan temple constructed by Hadrian was already in ruins—destroyed by zealous Christians.

After Queen Helena’s visit, the Christian community proceeded to remove whatever was left of the Hadrianic temple, as well as the Hadrianic enclosure and the fill it contained. For the Christian community, this fill, intended by Hadrian to create a level surface for building, represented Hadrian’s attempt to obliterate forever not only Jesus’ tomb, but the adjacent rock of Golgotha where he had been crucified.

According to literary sourcesh Constantine built a rotunda around Jesus’ tomb. In front of the rotunda was the site of the crucifixion (Golgotha or Calvary), in what is referred to in ancient literary sources as the Holy Garden. On the other side of the garden, Constantine 037built a long church in the shape of a basilica, consisting of a nave and side aisles separated from the nave by rows of columns. Here the faithful could offer prayers. Between the rotunda and the basilica lay the hill of Golgotha.

Was the Constantinian rotunda actually built over the true site of Jesus’ burial?

Although we can never be certain, it seems very likely that it was.

As we have seen, the site was a turn-of-the-era cemetery. The cemetery, including Jesus’ tomb, had itself been buried for nearly 300 years. The fact that it had indeed been a cemetery, and that this memory of Jesus’ tomb survived despite Hadrian’s burial of it with his enclosure fill, speaks to the authenticity of the site. Moreover, the fact that the Christian community in Jerusalem was never dispersed during this period, and that its succession of bishops was never interrupted supports the accuracy of the preserved memory that Jesus had been crucified and buried here.

Perhaps the strongest argument in favor of the authenticity of the site, however, is that it must have been regarded as such an unlikely site when pointed out to Constantine’s mother Queen Helena in the fourth century. Then, as now, the site of what was to be the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was in a crowded urban location that must have seemed as strange to a fourth-century pilgrim as it does to a modern one. But we now know that its location perfectly fits first-century conditions.

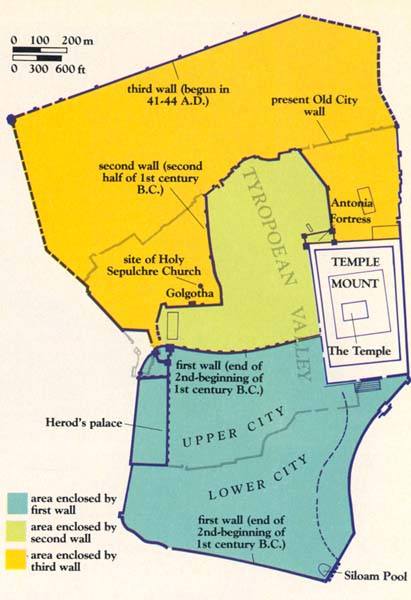

In the fourth century this site had long been enclosed within the city walls. The wall enclosing this part of the city (referred to by Josephus as the Third Wall) had been built by Herod Agrippa the local ruler who governed Judea between 41 and 44 A.D. (see map). Thus, this wall was built very soon after Jesus’ crucifixion—not more than 10 or 15 years afterward. And that is the crucial point.

When Jesus was buried in about 30 A.D., this area was outside the city, in a garden, Corbo tells us, certainly in a cemetery of that time. These are the facts revealed by 038modern archaeology. Yet who could have known this in 325 A.D. if the memory of Jesus’ burial had not been accurately preserved?

The Gospels tell us that Jesus was buried “near the city” (John 19:20); the site we are considering was then just outside the city, the city wall being only about 500 feet to the south and 350 feet to the east. We are also told the site was in a garden (John 19:41), which is at the very least consistent with the evidence we have of the first century condition of the site.

We may not be absolutely certain that the site of the Holy Sepulchre Church is the site of Jesus’ burial, but we certainly have no other site that can lay a claim nearly as weighty, and we really have no reason to reject the authenticity of the site.

The basilica Constantine built in front of the tomb was typical of its time. It consisted of a center nave and aisles on either side of the nave separated from the nave by rows of columns. At the far end of the nave was a single apse. Unfortunately hardly a trace of Constantine’s basilica church remains. From the sections of wall discovered, we can only confirm its location and former existence.

Behind (west of) Constantine’s basilica was a large open garden on the other side of which, in the Rotunda, stood 040the tomb of Jesus. The apse of the basilica faced the tomb. Two principal scholars involved in the restoration disagree as to when the tomb was enclosed by a large, imposing rotunda. Corbo takes one view; Father Charles Coüasnon takes another. Coüasnon, who died in 1976, had been the architect of the Latin community in connection with the restoration work. In 1974 he published a preliminary report of the excavations, entitled The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, (London: Oxford University Press).i

According to Coüasnon the tomb was set in an isolated square niche annexed to the Holy Garden. Coüasnon believed the tomb remained exposed to the open air until after Constantine’s death, at which time the rotunda was built around it, leaving the Holy Garden between the rotunda and the back of Constantine’s basilica church.

This view is rejected by Corbo who is probably correct. According to Corbo, the rotunda was part of the original Constantinian construction and design. Unfortunately, from the nature of Corbo’s excavation methodology and the limited archaeological evidence in this report, it is impossible to check his dating of walls.

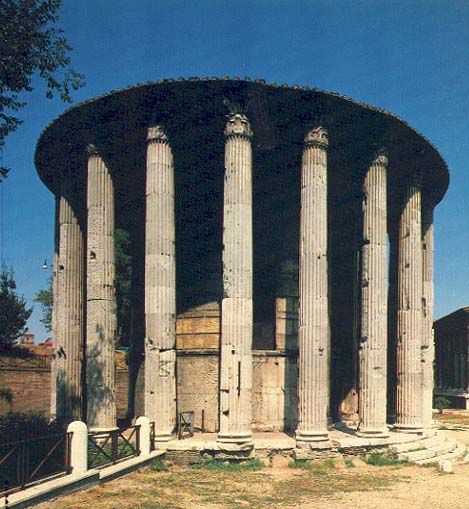

There is one argument Corbo fails to make, however, that might well support his position; many temples to goddesses (like Venus/Aphrodite) are round, in the form of rotundas. If it is true, as Eusebius says, that Hadrian had built a temple to Venus/Aphrodite here, it was quite probably a round temple. The Christian rotunda may well have been inspired by this pagan rotunda. (The phenomenon of a holy site from one religion being maintained as holy by subsequent religions was a common one throughout the ancient world.) If the architecture of Hadrian’s pagan rotunda inspired the rotunda around Jesus’ tomb, it is more likely that the later rotunda was built by Constantine himself, not by a later ruler who would not have known the pagan rotunda.

Two original columns of the rotunda built around Jesus’ tomb have been preserved. Father Coüasnon suggested they were two halves of what was once a single, tall column. According to Coüasnon, this column had previously served in the portico of the Hadrianic temple; the two halves were later reused in the rotunda. In this, he is probably correct.

043

On the side of the niche that marked Jesus’ tomb, a drain had been cut in the rock, apparently to allow the flow of rain water from the tomb. This might indicate that at least for some time the tomb stood in the open air. How long we cannot know.

In any event, a rotunda was soon built around the tomb where the current reconstructed tomb—the focus of the present church—now stands. This rotunda is often referred to, both now and in historical records, as the Anastasis (“resurrection”).

Between the rotunda and the basilica church was the Holy Garden. According to Coüasnon, the Holy Garden was enclosed on all four sides by a portico set on a row of columns, thus creating a colonnaded, rectangular courtyard. Beyond the porticoed courtyard, on the rotunda side, was a wall with eight gates that led to the rotunda. Corbo, on the other hand, reconstructs columns on only three sides. (Thus, he calls the garden courtyard the triportico.) Corbo would omit the portico on the rotunda side, adjacent to the eight-gated wall. He is probably right.

Thus the complex of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre stood until the Persian invasion of 614 A.D. At that time it was damaged by fire, but not, as once supposed, totally destroyed. When the Persians conquered 044Jerusalem, they destroyed many of its churches, but not the Holy Sepulchre.

The situation was different, however, in 1009 A.D. On the order of the Fatimid Caliph of Cairo, El Khakim, the entire church complex—the basilica, the rotunda, the tomb inside the rotunda and the portico between the rotunda and the basilica—was badly damaged and almost completely destroyed.

The basilica was gone forever, razed to the ground. Only the 1968 discovery of the foundation of the western apse of the basilica allows its placement to be fixed with certainty (although previous reconstructions had fixed its location correctly).

The rotunda, however, was preserved to a height of about five feet. Between 1042 and 1048 the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus attempted to restore the complex. He was most successful with the rotunda, which was restored with only slight change (see plan). Where the Constantinian rotunda had three niches on three sides, Monomachus added a fourth. This new niche was on the east side, the direction of prayer in most churches. The new niche was the largest of the niches and was no doubt the focus of prayer in the rotunda.

In front of the rotunda, Monomachus retained the open garden. One of the old colonnades (the northern one) was rebuilt by him and has been preserved to the present time, thus enabling us to study the character of Monomachus’s restoration.

Instead of a basilica, Monomachus built three groups of chapels. One group, consisting of three chapels, abutted the old baptistery; a second group, also consisting of three chapels, was built near the site of the apse of the destroyed basilica (this group is known from historical documentation only); and the third consisted of a chapel north of the rotunda.

In the course of his reconstruction, Monomachus discovered a cistern where, according to tradition, Queen Helena had discovered the True Cross. Corbo believes, probably correctly, that this tradition originated only in the 11th century. (On archaeological grounds, the cistern dates to the 11th or 12th century.) Moreover, nothing was built to commemorate Helena’s supposed discovery of the True Cross here until even later, in the Crusader period. Coüasnon, on the other hand, believed the tradition that Queen Helena found the True Cross here dated from Constantinian times. According to Coüasnon, Constantine built a small crypt in the cave-cistern. Coüasnon recognized, however, that the current chapel of St. Helena dates to the Crusader period. At that time, the famous chapel of St. Helena, which is a focus of interest even now, was constructed partially in and partially adjacent to the cistern.

The Crusaders, who ruled Jerusalem from 1099 to 1187, also rebuilt the church, essentially in the form we know it today. The rotunda (or Anastasis) enclosing the tomb was maintained as the focus of the new structure. In the area of the porticoed garden in front of the rotunda, the Crusaders built a nave with a transept, forming a cross, and installed a high altar.

The traditional rock of Golgotha, where Jesus had been crucified, was enclosed—for the first time—in this church. In Hadrian’s time, the rock of Golgotha had protruded above the Hadrianic enclosure-platform. According to Jerome, a statue of Venus/Aphrodite was set on top of the protruding rock. This statue was no doubt removed by Christians who venerated the rock. When Constantine built his basilica, the rock was squared in order to fit it into a chapel in the southeast corner of the Holy Garden. As noted, in the Crusader church the rock was enclosed in a chapel within the church itself. The floor level of this chapel, where the rock may still be seen, is almost at the height of the top of the rock. Because of this, a lower chapel, named for Adam, was installed to expose the lower part of the rock. This lower chapel served as a burial chapel in the 12th century for the Crusader kings of the Later Kingdom of Jerusalem. These tombs were removed after the great fire of 1808.

Father Corbo’s book may well be the last word on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for a long time to come. Despite its monumental nature, it is, alas, not beyond criticism. It is in no sense an archaeological report, despite the reference in the title of Corbo’s book to the “archaeological aspects” of the site. Almost no finds are described and it is impossible to understand from Father Corbo’s plates and text why a particular wall is ascribed to one period or another. This is a pity. Precise descriptions of these finds and their loci would have increased our knowledge significantly, not only with respect to the history of the church, but also with respect to the study of medieval pottery, coins and other artifacts. It is also 045important that scholars be able to check for themselves the attribution of walls and other architectural elements. In photograph No. 207, for example, we are shown a fragment attributed by Corbo to Baldwin V’s tombstone, but it is almost impossible to understand where it was found, as only a general location is mentioned.4 Unlike many archaeological reports, Corbo gives us no loci index. Thus anyone who wishes to study thoroughly a particular locus, its contents, location and attribution to a particular period is completely stymied.

Corbo has provided no plans superimposing various periods. There is no grid where one can reconstruct the continuity of the various walls and their relation to one another. One must rely solely on the author’s assumptions. He apparently justifies his attribution of walls and floors to particular periods principally on his concept of the shape of the church in a particular period.

There are other shortcomings: The meaning of the shading in some of the plates is not always given in the legend, so it is not always clear what the shading refers to. The location of the sections is not always shown on the plans, so, for example in plate 52, it is not clear where the section of the cistern in plate 53 is located.

No heights are marked on the plans. Thus, for example, when we examine the author’s extremely important reconstruction of the pagan structure that preceded the rotunda, we cannot know whether a certain wall is a retaining wall, which it probably was, or a free-standing wall.

From the archaeological point of view, the book under review is definitely unsatisfactory. There is not even a discussion of the stylistic development of the building—the rotunda, for example, or the Crusader church as part of the development of the Romanesque European church. Nevertheless, no student of this great structure can afford to be without these volumes.

Since 1960, the Armenian, the Greek and the Latin religious communities that are responsible for the care of the Holy Sepulchre Church in Jerusalem have been engaged in a joint restoration project of one of the most fascinating and complex buildings in the world. In connection with the restoration, they have undertaken extensive archaeological work in an effort to establish the history of the building and of the site on which it rests. Thirteen trenches were excavated primarily to check the stability of Crusader structures, but these trenches also constituted archaeological excavations. Stripping plaster from the 028walls revealed structures […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme, Aspetti arceologici dalle origini al periodo crociato. Parts I–III (Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press, 1981–1982).

In 1960 he was appointed archaeologist for the Latin community on the project; in 1963, for the Greek and Armenian communities as well.

Nefesh literally means “soul.” In rabbinic literature, it also refers to a monument constructed over a grave as a memorial to the deceased. In contemporaneous Greek inscriptions, the equivalent term is stele.

See Nancy Miller, “Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years,” BAR 11:03.

Moreover, in the reconstruction itself, Wall T 62 C has no function. Wall T 10 G with two angles makes no sense at all.

If Corbo intended as his model the Maison Carée in Nîmes, France, or the Temple of Fortuna in Rome, both of which were contemporaneous with Hadrian’s temple on the site of the future Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Corbo failed to follow his models. The staircase should not occupy the whole breadth of the structure; behind the six interior columns there should be two additional columns enclosed in two antae, arm-like walls that extend from the main walls of the structure; and the lateral columns should not be freestanding, but only half columns attached to the side walls.

Especially Eusebius, Life of Constantine (Palestine Pilgrims Texts Society, Vol. I, 1891), pp. 1–12.

See J.-P. B. Ross, “The Evolution of a Church—Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre,” BAR 02:03.

Endnotes

See Magen Broshi, “Recent Excavations in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre,” Qadmoniot, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1977, pp. 30ff (in Hebrew). More recently, see Magen Broshi and Gabriel Barkay, “Excavations in the Chapel of St. Vartan in the Holy Sepulchre,” Israel Exploration Journal 35, Nos. 1–3 (1985), pp. 108ff.

Broshi and Barkay do not mention this layer of arable soil; instead they found an Iron Age II floor of beaten earth above the quarry fill. Based on this floor and the large quantities of Iron Age B pottery found below, in and above this floor, they conclude this area was residential from the late eighth century to the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem. They date the quarry mainly to the ninth-eighth centuries B.C. before the city expanded into this extramural area in the late eighth century. Corbo contends that this floor cannot be dated to Iron Age II.

Conrad Schick, “Notes from Jerusalem,” Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, 1887, pp. 156–170.