You can’t understand Christian origins unless you understand the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. So says Professor James H. Charlesworth of Princeton Theological Seminary, and he is clearly riding the crest of modern scholarship.

Nobody understands the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha better than Charlesworth. He is indeed Mr. Pseudepigrapha—the editor of a massive two-volume collection of these documents published in 1983 and 1985 under the title The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (TOTP). The reviewer for Biblical Archaeology Review called TOTP a “classic” from the day it was published. Volume I was the winner of a 1984 Biblical Archaeology Society publication award; Volume II won a special recognition from the judges for the 1986 BAS publication awards.

Nothing is easy about the Pseudepigrapha, however. Even defining the word can be tricky. According to Charlesworth, the definition given in the distinguished 1971 Encyclopaedia Judaica is “misleading and uninformed … anachronistic and distorted.” I believe him.

Actually, “pseudepigrapha” is plural. The singular is pseudepigraphon. A pseudepigraphic work is a writing (an epigraphon) attributed to some ancient figure who is not actually the author (hence, pseud-)—such as Adam, Enoch, Moses, Abraham, Solomon, Elijah, Ezra, etc. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha consist of Bible-like, Jewish writings mostly from about 250 B.C. to 200 A.D., that were not canonized in the Hebrew Scriptures. The form of these writings varies as much as the books of the Bible themselves. The Pseudepigrapha include apocalypses, prayers, psalms, visionary literature, oracles, apocalyptica and eschatologicalb literature, wisdom literature, philosophy, testaments, odes, and histories, to name just some of the overlapping categories. Charlesworth’s collection of Old Testament Pseudepigrapha contains 52 documents,c of which some are only fragmentary.

The Nag Hammadi Codices and Dead Sea Scrolls stand with the Pseudepigrapha as critical documents for understanding Christian origins.

With this new collection, the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha takes its place beside two other collections of ancient documents that are critical for understanding the origins of Christianity and its early development: the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Codices.d

The Nag Hammadi Codices are a collection of over 50 treatises found by two Egyptian peasants in a pottery jar on the bank of the Nile in 1945 near the village of Nag Hammadi. The Nag Hammadi Codices in their present form date to the mid-fourth century A.D., although of course they incorporate a great deal of older material.

The Nag Hammadi Codices differ from the collection of Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in several respects. For the most part, the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha date to the period 250 B.C. to 200 A.D. (although the extant copies are usually much later). Thus, on the whole the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha are older than the Nag Hammadi Codices. The latter are chiefly important for the study of early church history and the development of early church doctrine, especially in Egypt. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha are more pertinent to a study of Christian origins. Unlike the Nag Hammadi Codices, many of the Pseudepigrapha are contemporaneous with or even earlier than the documents in the New Testament.

The designation “Dead Sea Scrolls” refers to a large collection of scrolls and scroll fragments recovered since 1947 in 11 caves on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea overlooking the Wadi Qumran. Since the community that hid the scrolls in the caves was destroyed by the Romans in 68 A.D., no scroll dates later than this. The earliest community (or sectarian) document in the collection dates to about 150 B.C.

Both the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Codices are narrower collections than the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. The Nag Hammadi Codices are Christian documents committed to gnostice beliefs that differed radically from what emerged as orthodox Christianity. The Dead Sea Scrolls reflect the commitments of a sectarian group of Jews, probably Essenes, who violently opposed the Jewish establishment that controlled the Jerusalem Temple. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, on the other hand, are Jewish documents that must be taken to reflect widespread Jewish attitudes and beliefs inside and outside Palestine both during Jesus’ lifetime and during the early development of Christian doctrine.

All of the Nag Hammadi codices have been published, a superb accomplishment achieved under the direction of James M. Robinson at the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity and the Claremont Graduate School in Claremont, California.f By contrast, the failure to publish thousands of Dead Sea Scroll fragments is a major scholarly scandal that—we all hope—will soon be corrected.g

In contrast to these two collections of documents which were unknown before their discovery in the 1940s and 50s, the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha have long been known and consist of documents preserved in a variety of ways over the millennia.

Whatever interest was shown in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha before the 18th century stemmed almost exclusively from the mistaken belief that they were actually written by the biblical heroes to whom their authorship was attributed. Beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the European Enlightenment brought a new appreciation of man’s intellectual accomplishments in antiquity. In 1722 and 1723 J. A. Fabricius published the first major collection of Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, a two-volume collection of some Jewish documents translated into Greek and Latin.

In the first half of the 19th century—after the Napoleonic defeat at Waterloo in 1815—large crates full of ancient manuscripts and books were sent from the Middle East to the great European libraries. These crates included a number of Old Testament pseudepigrapha previously unknown in the West. Among the most sensational was the Book of Enoch,h which is actually quoted in the New Testament and which reflects a number of conceptual similarities to early Christianity.

In the early 20th century, two great collections of pseudepigrapha were published—one in German in 1900 by C. Kautzsch and the other in English in 1913 by R. H. Charles. Until the Charlesworth collection of the 1980s, R. H. Charles’s collection of 1913 was the standard English reference work on the subject.

Then came the First World War and a period of neglect that continued through the Second World War. The pseudepigrapha were considered sectarian writings on the fringes of a Jewish orthodoxy that ultimately evolved into normative Rabbinic Judaism. As the synagogue and the church both rejected them from inclusion in the canon, long after their composition, so too did the learned elite.

Fruitless search for the biblical theology turned scholars towards historical sources from Jesus’ time.

Prodded by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Codices, scholars have now rediscovered the Pseudepigrapha—or redirected their attention to them. Interest has been heightened by the fact that fragments of several pseudepigraphic works—Enoch, Jubilees, a version of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, and Melkizedek—have been found in the Dead Sea caves. These fragments can thus be confidently dated to before 68 A.D.

Professor Charlesworth contends there is another important cause of the renewed interest in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. It is what he calls the “Bankruptcy of Biblical Theology.” The most influential exponent of the Biblical Theology School was the New Testament scholar Rudolph Bultmann, for whom the proper subject of study for the New Testament scholar was the kerygma, the core redemptive message reflected in the New Testament texts, rather than the actual facts of history. For Bultmann and his school the focus was on the theological understanding of the early Christian communities, not on the tools that the historian provided for understanding the text of the New Testament. After the Second World War, a shift occurred; the search for the biblical theology proved unavailing.i At the same time, a number of prominent scholars independently suggested that history is to be found in the gospels, if properly examined, and that the pursuit of history is theologically legitimate. If the history in the gospels is important, it is a short step to affirming the importance of all sources of historical information to enlighten the period in which Jesus lived and Christian doctrine developed.

By now, as Charlesworth asserts, “almost all biblical scholars recognize that a study of the New Testament must include the sources contemporaneous with it.”

At the same time, the post-World War II period saw a fresh interest in Early Judaism. The Jewish writings in the Pseudepigrapha represent the cherished traditions and beliefs of many early Jews.

In this context, an international team of scholars was ultimately convened to produce a new edition of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. The team of scholars included, as Charlesworth tells us, “white and black, male and female, Christian and Jewish, and even a Falasha. They are specialists who work in the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, Holland, Germany, Poland, Greece, Israel and Australia.” In all, 52 scholars participated in the project, which culminated in the new English edition of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. At the same time translations into other languages either have appeared or will appear—Danish, modern Greek, Italian, German, French, Spanish and even Japanese.j In order to produce these new translations, the scholars must master not simply Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek, but also Coptic, Syriac, Latin, Ethiopic, Old Church Slavonic and Armenian, because these are the languages in which some of the pseudepigrapha have been preserved.

The new English edition of the Pseudepigrapha includes 52 documents, compared with 17 in Charles’s edition of 1913. Moreover, even those documents previously translated in Charles’s 1913 collection are given fresh adornment provided by more recent scholarship and the elimination of emendations too freely introduced by Charles’s translations in an effort to clarify difficult passages.

Since completing his work on the Pseudepigrapha in 1985, Charlesworth has published a short monograph “to assess the significance of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha for a better understanding of Early Judaism, Christian origins and especially the writings of the New Testament.”k Most of the material in this article comes from, or, more accurately, is lifted from, this monograph.

This juxtaposition of Early Judaism and Christian Origins makes it clear that Christian Origins cannot be understood and studied except in the context of Early Judaism. As Charlesworth puts it, “the origins of Christianity are inextricably rooted in Early Judaism.”

By Early Judaism Charlesworth refers to Judaism from about 300 B.C. to about 200 A.D. Early Judaism “denotes the beginnings of synagogue (modern) Judaism,” the transition from Biblical Israelite society and religion to Rabbinic Judaism.

Early Judaism was erudite and sophisticated, full of metaphysical speculations.

Although Charlesworth is ultimately concerned with understanding Christian Origins and Early Christianity, he repeatedly emphasizes the need to study Early Judaism for its own sake—on its own terms—and thus to study the Pseudepigrapha for their own sake, on their own terms. Charlesworth criticizes those who use the Pseudepigrapha “only to illustrate a theme, like the messianic kingdom and its banquet, a term, like the Son of Man, or a concept, like the belief in the bodily resurrection of the individual after death.” He castigates those who treat the Pseudepigrapha as “writings not to be understood, but to be mined.”

Early Jewish literature as reflected in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha “must be read thoroughly, sympathetically and reflectively before any attempt is made to compare them with socalled Christian documents …. any comparison between two very similar ‘religions’—such as Early Judaism and Early Christianity—must compare ideas, symbols and words in their full living context … [E]ach religion [Judaism and Christianity] must be understood holistically and compared as a whole with the other also understood as a whole. Both religions must be treated in precisely the same way, with the same justice and empathy. Each is to be understood on its own terms.”

This means that scholars studying Christian Origins and Early Christianity must intersect extensively with scholars studying Early Judaism per se. Since the dramatic discovery and revelations of the Dead Sea Scrolls, interest in Early Judaism per se has soared concomitantly as the number of texts has increased.

Lest it be thought that Early Judaism—and therefore Early Christianity—can be studied only on the basis of one collection, Charlesworth reminds us not only of collections like the New Testament, the vast rabbinic corpus, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Nag Hammadi Codices, writers like the historian Josephus and the philosopher Philo, and the Pseudepigrapha, but also of documents from the pagan-Hellenistic world. As non-Jewish elements were significant in the development of Early Judaism, so were they significant, both derivatively and directly, in the origin and development of Early Christianity. Both Early Judaism and Early Christianity were extensively influenced by foreign cultures.

The scholarly task is impossibly burdensome. As Charlesworth concedes, “No scholar today can claim to be a master of more than one ancient collection.” Indeed, Charlesworth questions whether it is possible “really [to] digest all that is in the Pseudipigrapha.” Thus are we prepared for the paradox: “Yet limiting oneself to one collection is a fatal flaw.”

Having declared the impossibility of the undertaking, there is no alternative to undertaking the task. Naturally Charlesworth emphasizes the Pseudepigrapha.

His major conclusion is that Early Judaism, especially as reflected in the Pseudepigrapha, was erudite and sophisticated, alive and full of highly developed metaphysical speculations and introspective perceptions into the psychological complexities of being human:

“Early Judaism was characterized by amazing erudition and by brilliantly articulated and highly advanced concepts and perceptions.”

The first-century Jewish historian Josephus described four different Jewish sects—Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots—that are sometimes thought to exhaust the categories of Jewish groupings of the time. The pseudepigraphaic writings bankrupt this notion:

“Seeing Early Judaism through four sectarian windows is myopic and unperceptive. A sensitive investigation of Early Judaism leads to the discernment of other groups; we must include in our description (at least) also the Hasidim, the Hellenists, the Nazarenes, the Samaritans, the Boethusians, the Herodians, the Hemerobaptists, the Masbothei, the Galileans, the mystics, the apocalyptic groups, the baptist movements led by John the Baptist, and others, perhaps including Jesus of Nazareth at the beginning of his public ministry, and the early followers of Jesus.”

Pseudepigraphic writings bankrupt the notion that Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots were the only Jewish sects in the first century.

Moreover, both Philo and Josephus tell us that the vast majority of Jews belonged to no sect. And as Charlesworth notes “Secular Jews probably did not write literature; they wrote legal and economic documents that almost always have not survived.”

Charlesworth concludes:

“I am convinced that our customary sectarian approach to Early Judaism is inappropriate, and that reference to four major sects is no longer adequate if we want to portray sensitively religion and daily life in Early Judaism.”

The increased perception of the complexities in Early Judaism has led to a “corresponding hesitation to attribute any early Jewish document to one of the four great sects.” In Charlesworth’s edition of the Pseudepigrapha, not a single document is assigned, for example, to the Pharisees—or to any other sect.

As Charlesworth observes:

“We know far too little about the sects, The only sources for the Pharisees are the New Testament writings, Josephus, and a few paragraphs in the Mishnah; and certainly we all agree that these are tendentious and heavily edited. The Pharisees were far more latitudinarian than either our publications portray or the debates between Hillel and Shammai convey. A legalistically oriented Pharisee, for example, may have been closer in many ways to a Sadducee than to an apocalyptically-inspired fellow Pharisee. The Essenes likewise were subdivided into separate groups: some were celibate and monastic, others married and raised families. The Zealots, the last sect to appear of the popularly conceived ‘four sects,’ may have arisen only around 66 C.E. and they need to be distinguished from the brigands and the sicarii.”

As we appreciate the complexities of Early Judaism, the concept of “normative Judaism” in this period must be abandoned; nor can we succeed in a search for the “essence” of Early Judaism. The search for an essence “does not allow for the fundamental diversities in Early Judaism.” It is impossible, Charlesworth says, “to extract from the extant documents a systematic theology of Early Judaism.

“The old portrait of a normative Judaism has been shattered by the vast amount of new literary evidence from Early Judaism, especially the documents gathered together in the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha.” As is generally agreed among scholars and as Charlesworth puts it quite succinctly:

“The concept of a normative Judaism result[ed] primarily from a tendency to read back into pre-70 Judaism [before the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.] the ‘religion’ found in much later, heavily edited rabbinic texts, and secondarily from the incorrect impression that Paul inaccurately portrayed a Judaism with a normative system. Most scholars have come to discard the concept of normative Judaism for pre-70 phenomena, but a few scholars linger on with this and other anachronistic models.”l1

We must be careful not to read post-70 circumstances (after the Roman destruction) back into the period of Christian Origins.

“Far too often New Testament scholars have claimed to have painted an accurate picture of Early Judaism, when in fact they have read back into the period before 70 much of the tension and the distasteful anti-Jewish polemic that we have all perhaps reluctantly, come to admit is characteristic of Paul’s polemical utterances, and of the Tendenzen in Matthew and John. If a New Testament scholar wishes to understand Early Judaism he or she must listen sensitively to all of the extant literature.”

Early Palestinian Christianity was never “primitive,” even at its beginnings; many highly developed ideas were transferred to Jesus.

What does all this tell us about Christian origins? Most broadly, it counsels for the abandonment of a concept like “primitive Christianity,” so long favored by scholars to describe early Palestinian Christianity. Charlesworth rejects the term because of what it implies: Christianity, he says, “did not evolve out of a dying mother, but out of a highly sophisticated, and phenomenologically complex Jewish ‘religion’ and culture. Christianity was the heir of over a thousand years of traditions, both written and oral. Christianity arose in a cosmopolitan Jewish culture which was impregnated after the exile repeatedly by influences from Babylon, Egypt, Persia, Syria, Greece, Parthia and Rome.”

In short, Christian theology was capable of highly developed sophistication at a very early time and in Palestine. It is not necessary to posit a later development in the Hellenistic world outside Palestine.

“The first generation of Jews converted to ‘Christianity’ was proficient in developed and sophisticated thoughts; … the earliest followers of Jesus, who were Jews, brought with them into the new Jewish movement that would be called ‘Christian’ this sophistication. The greatest development of thought in Early Christianity would probably have occurred in Palestine and in the decades from 30 to 75 and not elsewhere from 75 to 150.

“Early Christian thought did not have to move outside Palestine to be significantly affected by Greek and Roman ideas.

“Christology did not evolve, with unexpected jumps and mutations, but it developed out of pregnant elements ready for maturation. Without undermining the obvious significant development of Christian thought and Christology from 30 to 150, in the 30s, and even during Jesus’ public ministry, there were highly developed ideas. What was needed was not so much more development, as transference and specification. The transference to Jesus of many of the ideas already highly-developed about the Lord God and his messengers; the specification of Jesus as the one-who-was-to-come; for example, as the Messiah, as the Son of God, and as the Son of Man.”

After the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the burning of the Temple in 70 A.D., Judaism redirected itself; the Judaism—and the Jewish society—that emerged after 70 A.D. was far different from the variegated conditions that prevailed before the Roman destruction. The post-70 period saw the triumph of Rabbinic Judaism. But it is anachronistic to try to understand Christian Origins in terms of Rabbinic Judaism, even though New Testament documents written after 70 A.D. sometimes reflect a monolithic Rabbinic Judaism that did not obtain at the time of Jesus.

A recent study by Columbia University’s Alan F. Segal emphasizes that two new religions emerged in the first century—Judaism, as well as Christianity:

“The time of Jesus marks the beginning of not one but two great religions of the West, Judaism and Christianity. According to conventional wisdom, the first century witnessed the beginning of only one religion, Christianity. Judaism is generally thought to have begun in the more distant past, at the time of Abraham, Moses, or even Ezra, who rebuilt the Temple destroyed by the Babylonians. Judaism underwent radical religious changes in response to important historical crises. But the greatest transformation, contemporary with Christianity, was rabbinic Judaism, which generally became the basis of the future Jewish religion.

“So great is the contrast between previous Jewish religious systems and rabbinism that Judaism and Christianity can essentially claim a twin birth. It is a startling truth that the religions we know today as Judaism and Christianity were born at the same time and nurtured in the same environment.”m

Judaism before 70 A.D. was filled with apocalyptic speculations, reflected in the Pseudepigrapha.

In searching for Christian Origins, we must be careful to seek it in pre-70 Judaism, not in post-70 Rabbinic Judaism. The roots of Rabbinic Judaism can also be found in pre-70 Judaism, but the difference between what Charlesworth calls Early Judaism (pre-70 Judaism) and Rabbinic Judaism as it emerged after the Roman destruction of the Temple are profound.

In the post-70 period, Judaism developed “into a more systematized, organized, so-called normative structure of Judaism.”

“What is missing in the rabbinic writing and so pervasively characteristic in Early Judaism, is the thoroughgoing, categorically eschatological form and function of thought and life.” In short, pre-70 Judaism, or Early Judaism, as Charlesworth calls it, was filled with apocalyptic speculations and apocalypticism, of which there is relatively little evidence in later rabbinic literature, but which is abundantly evidenced in the pre-70 literature—narrowly for the Essenes in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but much more broadly for Judaism in general, in the Pseudepigrapha.

As Charlesworth says, “The Pseudepigrapha opens our eyes to a cosmos full of activity.” The apocalypticism that pervades so many New Testament writings is often paralleled in contemporaneous Jewish literature.

An earlier generation of scholars looked on Christian apocalypticism as sui generis or perhaps related to Hellenistic religion outside of Palestine. Muses Charlesworth: “How odd it is to be told [as a previous generation of scholars told us] that Early Christianity is so different from Early Judaism because the Christian doctrine cannot be extracted from it.” We are just beginning to penetrate this relationship—especially as a result of discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the renewed interest in the pseudepigrapha. The process of understanding is just developing: “We are entering a new phase in research in Early Judaism and Christian Origins.” Christianity’s inheritance from Early Judaism is not only “rich,” it is complex.

At the outset, we are faced with the problem of dating the pseudepigrapha. Dating is not quite so great a problem with respect of the Dead Sea Scrolls; the community that preserved them was destroyed by the Romans in 68 A.D.

This so-called terminus post quem is not available for the Pseudepigrapha. The extant manuscripts are all later—much later (except for the fragments of pseudepigrapha found among the Dead Sea Scrolls). And their compositional history is complex. The objective is to get behind the text that has survived, to strip away the layers, to see by whom and when a pseudepigraph was written and then to determine the textual influences to which it was subjected.

The dating of each pseudepigraphic document must be considered separately—this gives some idea of the task facing scholars.

Sometimes there is simply not enough evidence and the original composition cannot be confidently dated at all. Often it is difficult to determine whether a document is of Jewish or Christian origin. Most early followers of Jesus were Jews. To label them Christians may itself distort our view. Moreover, a Jewish composition may have been edited later and interpolations added from a Christian viewpoint. Yet, on occasion, it may be possible to reconstruct, at least tentatively, the Jewish sub-stratum of the document.

Despite the textual difficulties, scholars have been surprisingly successful in unscrambling the history of many pseudepigraphic works. Charlesworth lists eight works that are “clearly” pre-Christian Jewish documents and ten more that “probably” fit into this category. Another fourteen compositions are later, but contemporaneous with New Testament writings of the second century, so should be helpful in understanding the background of these writings.

1 Enoch, Jubilees and some of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs have been shown to be pre-Christian Jewish documents.

The three principal pre-Christian Jewish documents are 1 Enoch, some of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs and Jubilees.

Jubilees is the clearest case. Fragments from 14 different copies of Jubilees have been found in the Dead Sea caves. It is free of Christian interpolations and redactions and was probably written shortly before 150 B.C., antedating the establishment of the Essene community at Qumran.

1 Enoch is more complicated. Fragments of it too have been found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. These parts of the work are clearly Jewish and pre-Christian, but we have only fragments from so early a date. Since 1 Enoch is a composite document that may combine six separate works including a lost Book of Noah, each part of the work must be assessed separately. Nevertheless, Charlesworth tells us

“The results of labours by scholars throughout the world have moved us far away from a level of exasperation or frustration when working with 1 Enoch … It is now clear that specialists on 1 Enoch at present affirm not only its Jewish character but also its pre-Christian, or pre-70 date; and that Judgment pertains to all segments of this composite work.”

As to the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, there is less consensus. In its present and final form it is a Christian document. Nevertheless, in Charlesworth’s words it is “not a Christian composition, but a Christian redaction of earlier Jewish testaments.” Indeed, fragments of the Testament of Levi and the Testament of Naphtali in Hebrew were found in the Dead Sea caves, assuring us that at least these two of the 12 are Jewish and pre-Christian. (Charlesworth complains that the editor who was assigned publication rights to these fragments, J. T. Milik, has not yet published them so the texts themselves are unavailable to scholars. See the first sidebar to this article.) Charlesworth concludes:

“I have no qualms about stating boldly that it is highly probable that behind each one of the twelve testaments in the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs there is a Jewish substratum which can be reconstructed tentatively once the clearly Christian redactions and interpolations have been identified.”

Thus, pseudepigraphic documents like these can be used in reconstructing Christian origins and the history of Early Christianity. The point is emphasized by the fact that only two collections of ancient Jewish documents are quoted in the New Testament: the Old Testament and the Old Testament pseudepigrapha.

We may close with two examples of how pseudepigraphic writings are used in New Testament research. The letter of Jude is one of the so-called general epistles of the New Testament, not addressed to a particular Christian community. The author of this epistle challenges the reader to contend for the true faith and inveighs against the inroads of heretics who “set up divisions,” perhaps a reference to an early sect of gnostics—and here Jude (verses 14–15) quotes from the Book of Enoch to show that these things had been prophesied.

The Letter of Jude adapts Enoch for a Christian audience.

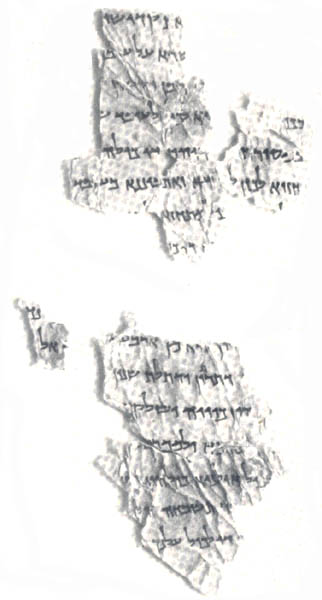

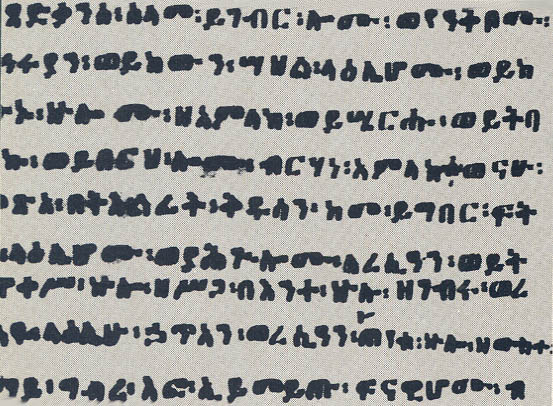

Jude not only says that he is quoting from Enoch, but we have a late Ethiopic version of Enoch with which to compare it. (See second sidebar to this article.) Moreover, we can be confident that this part of Enoch is Jewish and pre-Christian because a fragment of precisely this passage was found in the Dead Sea caves written in Aramaic, not Ethiopic; and the handwriting of this fragment allows us to date it to the first century B.C.

When Jude quotes Enoch, however, he makes some significant changes in the text. Jude alters the text of Enoch so that the prophecy of the coming of the Lord—which Jude takes to be a prophecy of Jesus—has been fulfilled, rather than, as in Enoch, that it will be fulfilled. According to Jude, Enoch prophesied: “Behold the Lord came with his holy myriads, to execute judgements against all.” But Enoch in fact prophesied: “Behold he will arrive with the myriads of the holy ones to execute judgment upon all.” As Charlesworth says, “For Jude, Christ came and accomplished his task; in the light of this he will return, as Enoch had prophesied about God.” Jude freely alters the text he quotes within what was regarded as acceptable bounds to prove his interpretation.

Moreover, not only does Jude change the future tense in Enoch to the past tense,n but “Lord” (Kurios) is used instead of “he” Thus, Jude “has made a decidedly Christian adaptation of 1 Enoch.” By changing “he” to “Lord” (Kurios), Jude may be applying a prophecy of the eschatological coming of God to Christ’s first coming, but also to the Parousia, his anticipated imminent second coming.

In addition, Jude refers to “his” holy ones, while Enoch actually says “the” holy ones. In short, Christ possesses the holy legions; they are “his.”

Charlesworth tells us:

“As most interpolations are alterations by Christians of Early Jewish writings, the alteration is caused by Christology. He—that is Christ—is ‘the Lord’. … In most cases as in Jude 14–15, the alteration of an earlier Jewish quotation is precisely because of the belief in the advent of the one-who-was-to-come The commitment to Jesus as the Christ, the Messiah shifted inherited parallel verbs and nouns according to the light shown upon the text, altering, these traditions like light passing through a prism.”

Thus we see how early Jewish theology was transformed into Christology.

One more point is to be noted: Jude tells us that this passage from Enoch is a prophecy. Hence, “it is certain the author of Jude considered the document [Enoch] inspired.” Charlesworth asks: “How can Christians discard as insignificant, or apocryphal, a document that is clearly pre-Christian, Jewish, and quoted as prophecy by an author [Jude] who has been canonized?”o

The example we have just considered is quite precise and detailed. Our second, and last, example is more general. It simply specifies in one respect the growing recognition of the Jewish background to some terms that took on a significant Christological meaning in early Christian communities. The most prominent of these is the title “son of man,” a title the Early church accorded Jesus (e.g. Mark 8:27, Matthew 16:17, etc.). The term is frequently used in the Old Testament, but without the messianic implications it is accorded in the New Testament, except, most notably, in Daniel. To understand when and why the son of man took on a Christological connotation, we must look not only to Daniel, but equally to Enoch. Although it was once disputed, it is now clear that the phrase as it appears in 1 Enoch is not an emendation, but is part of the original composition. It there refers to a celestial figure. Moreover, as Charlesworth says, the text is clear that Enoch himself is said to be the Son of Man. Just how Enoch influenced the early followers of Jesus is not yet clear, but it seems highly likely that it did. One scholar, George Nicklesburg, has suggested that Luke may have been personally acquainted with the man who translated Enoch into Greek; indeed, it may have been Luke himself who translated Enoch into Greek, so close are some of the similarities. In ways such as these do pseudepigrapha make their impress felt. Modern scholars ignore them at their own peril.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

Gnostic refers to the beliefs and practices of a variety of religious groups that relied on secret knowledge revealed only to a select few. Gnosis is the Greek word for this non-empirical insight.

See The Nag Hammadi Library in English, ed. by James M. Robinson and Marvin W. Meyer (San Francisco: Harper and Row; Leiden: Brill, 1977).

Earlier, in 1773, some manuscripts of Enoch were brought to Europe, but they were translated into English only in 1821 and into German only in 1833.

Surveying New Testament scholarship during the period 1926–1956, Professor Robert Grant observed that the only real advances were made by the critical scholars and historians, not by those scholars who were looking only for the message:“ The permanent achievements [of this period 1926–1956] were made by those whose goal was understanding rather than proclamation. They did not sell their birthright as critics and historians for what has been called a ‘pot of message’ ” (Robert Grant, “American New Testament Study, 1926–56,” Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 87, p. 50 [1968]).

In addition a selection of the major Pseudepigrapha was published in 1984, edited by H.F.D. Sparks, The Apocryphal Old Testament (Oxford University Press).

On the other hand, we should not overlook the fact that in the first century the Romans recognized the Great Sanhedrin (Sanhedrin Gedolah) as the ruling body of Jews in Jerusalem. But as Charlesworth points out “an establishment must be distinguished from a normative theological system.”

It is also true that “without any doubt, the cult in Jerusalem was dominant.” But this went “hand in glove with a rejection of the priestly ruling class—considered by some religious Jews to be illegitimate—and the deep and ancient traditions that the present Temple is but an imperfect model of the future earthly, heavenly, or eschatological (perhaps messianic) Temple … The cult not only proved to be a unifying force in Judaism, it also tended to spawn differences, as the struggles for control, as well as the corruption within the priesthood, produced opposition.”

Rebecca’s Children, Judaism and Christianity of the Roman World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986). (See Bible Books)

Actually, in Greek it is in the aorist tense, signifying an event that was seen holistically as a past time. All the verbs used in Jude are in this aorist tense. The cumulative effect is to denote the end of a whole process.