Elie Borowski Seeks a Home for His Collection

018

Eliechish, his brothers called him. Elie the dreamer. He does not deny it; he is a dreamer. Today he is 71 years old and still dreaming. One of Elie Borowski’s dreams is 20 years old. Whether it will ever be realized is still an open question.

He tries to suppress his anger and frustration, but it spills out all over. “Please, Elie, don’t say it,” his wife pleads. He cannot be stopped; he is a compulsive talker anyway. He has given so much; why shouldn’t others be willing to do even a tiny fraction of what he has done?

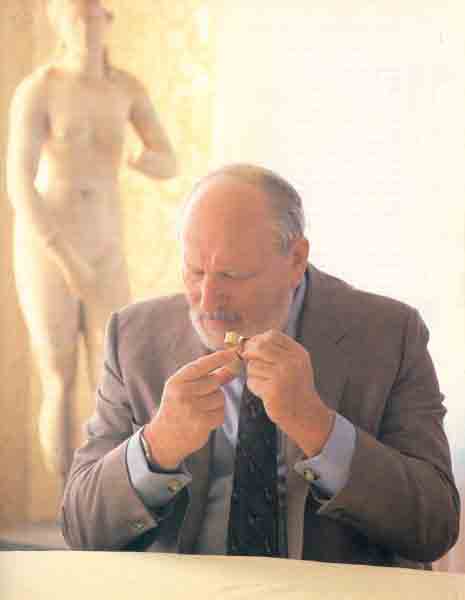

Elie Borowski is one of the last—perhaps the last—of the great scholar-dealer-collectors of Near Eastern antiquities. He has a doctor’s degree from the University of Geneva. He has published a fistful of arcane articles in learned journals. He has shaped collections for a dozen museums and private collectors. But above all, he has created his own collection—the crème de la crème, as he calls it, the finest and the rarest.

At his palatial home in Toronto, we were looking at his vast collection of ancient seals, in many ways the core of his collection. “Do you have any cylinder seal pins that hung on bracelets or necklaces?” I asked. “Don’t ask what I have,” he thundered. “Ask what I don’t have. Ask the Metropolitan what they have.” No one ever accused Elie Borowski of undue modesty.

He has something to be immodest about, major scholars agree. His collection of Achaemenian glyptics surpasses the National Museum’s in Teheran. It may even surpass that of the Hermitage in Leningrad. His Anatolian inscriptions are more varied than those in the Aleppo museum in Syria, which themselves surpass those in the Ankara museum in Turkey in this respect. Borowski has important Sumerian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Phoenician, Elamite, Hittite, Hurrian, Mittanian, Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, Roman and Byzantine pieces. Gorgeous original frescoes from Pompeii grace the walls of his living room. A stele from the child sacrifice cemetery at ancient Carthagea stands beside his indoor swimming pool. An 020important unpublished cuneiform tablet from Ebla lies in a drawer.

In the stilted prose of an official report, Dr. Wilfred G. Lambert, professor of Assyriology at the University of Birmingham, England, who made an independent study of the collection, concluded that “The Borowski Collection has more in quantity and of distinction than the national and other museums of certain Western countries which take an interest in Near Eastern antiquities and have full-time scholars professionally concerned with them.”

Borowski’s collection has a special relation to the Bible. That’s part of the dream. Ever since he started collecting, Borowski has concentrated on pieces that illuminate the Bible, that bring into dramatic relief the lands and cultures neighboring Israel, the area he calls the lands of the Bible. Although other collections may be stronger in a particular Biblical culture or civilization, his, says Borowski, is the most comprehensive collection of artifacts in the world relating to the lands of the Bible as a whole.

This is his dream: He would like his collection to be housed in a museum—his gift to mankind. Not just a building to display the collection, but a study center for scholars, a sponsor of excavations, a publisher of learned books and articles, a living museum that would grow and acquire new pieces to match the quality of the original collection. For this, he is willing to give his collection. No strings attached. No immortalizing the name of Elie Borowski. A gift, pure and simple. If only the world will do the rest. Therein lies the rub.

“The world doesn’t need to help me. The world needs to help itself,” he rages.

Borowski is a large, powerful man, full of energy and enthusiasm. He adores his collection. He knows each piece intimately and lovingly. He is also in a way a mystic. He believes he was marked for greatness from birth.

When he was only a few weeks old, he fell sick. His condition gradually worsened and his parents grew desperate. His father was a pious man, a patriarch, a flour merchant, who lived with his wife and family in a baronial house in Warsaw, the Paris of the east. What his father lacked in learning, he made up in piety, charity and good deeds. He had named his first three sons Avraham (Abraham), Itzchak (Isaac) and Yaacov (Jacob). The latest to be born was named Eliyahu (Elijah), for the prophet who ascended directly to heaven and who would someday return as the forerunner of the Messiah. When other remedies failed and Eliyahu’s condition continued to deteriorate, the elder Borowski decided to take his newborn son to a wonder-working rebbe several days’ journey from Warsaw. The rebbe blessed the child and gave him a second name. Henceforth he would be known in Israel as Eliyahu Chaim (Life). He would live, the rebbe said, because he was meant for a special destiny. The child recovered.

Elie was raised on the Torah and the Talmud. When he was 17 years old, he was sent to the famous Mir Yeshiva, where only the most brilliant students were accepted. His destiny at the time seemed to be that he would become a rabbi.

The Great Depression of the late 20s and 30s was not only an American tragedy. It had its effects even in Warsaw. The Borowski flour business failed. The elder Borowski grew sick and died—of a broken heart, says his son. Elie Borowski remembers the exact date and even the hour of his father’s death—the 23rd of Kislev, November 30, 1930, a Friday afternoon just before the beginning of the sabbath. The dying man called in his family to give his final testament, the patriarchal instructions. Elie had been studying at the Mir Yeshiva. Times would be difficult for the family, but “Elie should not be touched.” Whatever happened, he was to continue his studies. Those were his last words. The old man closed his eyes and died.

By 1932, Elie decided the Talmud was not enough for him. At the age of 19 he prevailed on his mother and older brothers to let him leave the Yeshiva and go to Berlin to study at a rabbinical seminary. He arrived penniless. He stayed with family friends and enrolled at the Orthodox Hildesheimer Seminary,b where he was exposed to extra-talmudic studies. Very soon, however, the Hildesheimer was itself not enough. Elie moved up the street to the Juedische Hochschule,c the Reform rabbinical seminary, where he added Maimonides and such philosophers as Spinoza to his studies with world famous teachers. It was the young scholar’s first taste of a secular education.

By his own account, however, he did not get on well in Germany. Even at this early date, he had a premonition. He somehow knew that Hitler was coming. He argued with his fellow students, but they would not listen.

In October 1932, he left Berlin and went to Florence. There he enrolled in the Collegio Rabbinico Italiana. He still assumed he would become a rabbi. But he also enrolled at the University of Florence, where he studied 021literature, philosophy and science. His average grade, he says, was summa cum laude.

In the summer of 1933, what he calls a spiritual change came over him. He decided he could not be a rabbi. He was not ready for the martyr’s life, as a true rabbi should be. And he didn’t want to be the other kind; he didn’t want to make his living from the Torah. He was on his way to a secular career.

In 1936, he returned to Poland to plead with his family to leave. By this time, at least for him, the writing was on the wall. The Jewish people, he felt, was facing disaster. His elder brothers, now mostly mature men with families of their own, wanted Elie to settle down. After all, he was 23 years old. He should marry well and have a family. Heartbroken, Elie left Warsaw and returned to Florence. Except for one brother who escaped to Russia and another who escaped to Australia, Elie never saw his family again. Some died in the Warsaw ghetto; others in the concentration camps.

Shortly after he returned to Florence, he was offered a fellowship at the Vatican’s famous Pontifical Biblical Institute to specialize in Assyriology. He accepted the fellowship and decided to devote his life to the scientific study of ancient civilizations. He wanted to understand how these civilizations, increasingly documented by contemporaneous texts, related to the culture of the Bible.

Borowski spent two and a half of the most satisfying years of his life at the Pontifical Biblical Institute. He learned to read cuneiform and became a specialist in its languages. He also became an expert in post-Biblical Hebrew.

In August 1938, however, he moved again, one step ahead of the Nazis. This time he went to Paris to study at the Louvre and the Collège de France. With the materials available in Paris, he was hoping to complete his doctoral dissertation.

In August 1939, he volunteered for a special Jewish unit of the French army to fight the Nazis. But France was woefully unprepared. His unit had neither uniforms nor weapons. Within weeks after the war started and Poland fell, Borowski was transferred to a Polish unit under the command of the French army because he was a Polish citizen. The Polish unit fought bravely and held its lines in southern France, but the French did not. On June 14, 1940, France surrendered to the Nazi juggernaut. Armed with World War I weapons, his unit continued to fight and to flee, to fight and to flee, finally reaching the Swiss border.

Neutral Switzerland interned all Allied soldiers crossing its borders. Borowski was one of them. Because he was fluent in Polish, German, Italian, French and English (his Hebrew, Yiddish, Akkadian and Sumerian were less useful), he served as an interpreter and as a janitor. After the battles of Stalingrad and El Alamein, however, when it became clear that the tide was turning in favor of the Allies, Borowski was transferred to Château de Céligny, about 12 miles from Geneva, where the higher echelons of the Polish officer corps were living. In late 1943, in the midst of some of the bitterest fighting of the war, Borowski was given permission to spend one half of each day at the Museum of Art and History in Geneva.

Borowski believes that some mystic force led him by this strange series of events to the Geneva museum. It changed the direction of his life. Until then he had been an epigraphist, specializing in ancient cuneiform languages. But the Geneva museum had few cuneiform tablets. It did, however, have a fine collection of ancient seals produced by the same cultures that had written the tablets. At the Geneva museum, Borowski launched his career as an ancient art historian. There he studied the ancient seals, trying to connect the tiny art on the seals to the texts he already knew so well. Almost instantly, he was captivated by the quality of the art and the stories it told. There too he felt the first faint stirrings of acquisitiveness. Before 1943 was over, he had bought two ancient seals on the antiquities market, one prehistoric and the other containing an ancient Hebrew inscription. The latter is now on exhibition at the Israel Museum, on loan from Borowski.

In 1944, he published a scholarly article in the journal Genava connecting the seals he was studying with the epic saga of Gilgamesh. As a result, he was soon being consulted by dealers and collectors who sought his advice. Then he published the first of a projected four-volume set on seals in Swiss collections. The other three volumes never appeared, but the first one was enough to establish him as an expert. He was inundated by letters from all over the world seeking his counsel. Soon he was assisting collectors who would pay him in kind with pieces from the collections they were buying and selling.

He remembers on one occasion being invited to tea by an elderly woman who, in gratitude, had tied a ribbon around an ancient seal that she set beside his cup—a lagniappe with his tea. It was the now famous ladders-to-heaven seal that became the theme of an exhibit from his collection.

When he established himself as a dealer, his commissions brought him ten percent of all that passed through his hands.

The war ended and Borowski remained in Switzerland. In 1946, he received his doctor’s degree from the University of Geneva. In 1947, he went back to Poland; everything and everyone he had known was gone. To leave Poland he needed the permission of the Polish 022authorities. Permission was granted, but only if he gave up his Polish passport. He agreed—and became a stateless person.

He returned to Switzerland, but in 1949 he sailed to Canada to accept an invitation from the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto to become a Lady Davis Fellow. He stayed and became a Canadian citizen. When Canada allowed him, a stateless person, to become a citizen, it earned Borowski’s eternal gratitude.

In 1958, he moved back to Switzerland, however. He set up a residence in Basel and remained there for 22 years. He became one of the world’s leading dealers and collectors, parlaying one piece into another, one collection into another, establishing links with dealers, collectors and villagers all over Europe and the Near East.

The 1950s and 1960s he describes as a “super-paradise.” Because of the dislocations of the war, old collections were becoming available. And amid the feverish political activity in the Middle East, new pieces were being uncovered. Elie Borowski was at the center of it all. In remote areas of the Middle East, he boasts, they were selling his address. On one occasion, a villager brought him a rare piece for which he simply gave the villager a signed check with the amount blank. He instructed the villager to fill in his own price. Borowski became a legend.

Given Borowski’s background, it is natural to ask, where was Israel in this picture? Elie Borowski loves Israel deeply, but mostly because he can’t help it. He wanted Israel’s museum to have the greatest collection in the world. And he would be the instrument by which this could happen. In the years following the creation of the state, he tried to interest the leaders of the young state in acquiring what was coming onto the market. “Treasures were passing through my fingers,” he recalls. He spoke with Zalman Shazar, who later became president of Israel and Executive of the Jewish Agency. He spoke with Golda Meir, with Moshe David Remez, minister of education—but they had “greater worries.” He pleaded with scholars, but they had no money. He could have built a third temple, he says, “not a real third temple, but a temple of treasures.”

The opening of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem in 1960 included seven special exhibitions. Two of the seven, a selection of Near Eastern antiquities and a selection of ivories and inscriptions, were made up almost exclusively of objects lent by Borowski. He brought some of the world’s most prominent collectors and potential donors to the opening. Somehow he was badly treated, and the occasion was a deep disappointment to him. Part of the trouble arose from the fact that Borowski identified the featured piece of the entire exhibition—a life size head of King Gudea of Lagash—as a fake! Someone suggested that Borowski did this because the Gudea head had been acquired for the museum by another dealer, not by Borowski. It was not a pleasant scene. Borowski concedes he is “a genius at making enemies.” And even his admirers say he is sometimes “too blunt.” But he was right about the Gudea head. Five years later the museum admitted its Gudea head was not genuine and quietly took it off exhibit. Recently, Teddy Kollek told Borowski it is being used as a paperweight in an assistant curator’s office.

In 1976, Borowski created The Lands of the Bible Archaeology Foundation to find a permanent home for his collection in Canada. Borowski allocated to the Foundation more than 1,700 artifacts, consisting of approximately 1,200 of his finest seals and 500 other rare Near Eastern artifacts. Borowski created the Foundation in Canada in gratitude for its having given him, a stateless person, citizenship and a new start in life after the war. As a Foundation brochure stated, Borowski “has special reasons for wishing to locate it [the collection] here.” The Foundation’s president was the chief archaeologist of the Royal Ontario Museum and a scholar of very considerable prominence, Dr. A. D. Tushingham. The Foundation’s board included well-known Canadian politicians, as well as scholars.

The agreed-upon plan was that the Foundation would initially raise $150,000 from private sources to mount an exhibit. It would then create a multi-million-dollar endowment that would provide the Foundation with a $500,000 annual budget for new acquisitions, research, publications and exhibitions, both in Canada and abroad.

Again quoting from a Foundation publication:

“An opportunity has presented itself for Canada to acquire the finest available private collection in the world of Near Eastern archaeological art and artifacts. The collection can be brought to Canada with only modest initial funding.

“At the present time there is no collection of excellence in Canada for scholarly study or public display of Near Eastern archaeological art and artifacts. The Royal Ontario Museum is the only center with even moderate facilities. The acquisition of the Borowski Collection will, however, increase the importance of the Royal Ontario Museum facilities by at least ten times, establishing its augmented collection as one of the “Big Four” in its field in North America after the New York Metropolitan, the Oriental Institute of Chicago and the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania.

“In addition to the general prestige benefit to Canada, the augmented Royal Ontario Museum Collection will be of special importance to Canadian scholars, 024students and the public interested in the heritage of the Bible lands, cultures and civilizations. It will allow them access for the first time to a comprehensive collection of international status.”

The Foundation’s fundraising efforts can only be described as a total failure. Not a single substantial private contribution was received from anyone.

In order to mount an exhibition of about 300 items from the Foundation’s collection, Borowski agreed to the sale of one artifact belonging to the Foundation. For him, selling a piece from the collection is, he says, like committing hara-kiri. He suffers, he says, when he is unable to purchase a new piece that becomes available. Having to sell a piece he has owned and loved for years is worse. He has sleepless nights when, as he puts it, he must “renounce” a piece. He thought the Foundation board would learn the pain of selling and this would motivate them to get the Foundation off the ground. So he agreed to the sale.

The sale took place and the exhibition was mounted. It turned out to be far more popular abroad than it was at the Royal Ontario Museum. In Toronto, a city of 600,000, where Borowski claims it was not properly promoted, only 50,000 people came in 12 weeks. In Cologne, a city of about one million people, 95,000 turned out to see the exhibit in eight weeks.

When the exhibit returned to Toronto in 1982 after its worldwide tour, it was placed partly in a warehouse and partly in storage at the Royal Ontario Museum, where the rest of the Foundation’s collection has now lain for years.

In December 1982, Borowski married—for the third time. Batya is his new wife’s name. It means daughter of God. “Only the daughter of God is good enough for Elie Borowski,” she jokes. She is a warm, articulate, charming woman who laughs easily and heartily. The two of them interact as if they had been married a lifetime. He is still the patriarch, but she is his regulator.

Batya Borowski, too, believes in destiny. Batya’s father was from Yemen. In 1910, at the age of five, he walked with his family from Yemen to Jerusalem. As he later told his daughter, “I went home to Jerusalem.” For a while he became a commercial sailor. At a stop in Marseilles, he met and fell in love with a beautiful Jewish girl from Poland. He never returned to his ship. They married in Paris and went home to live in Jerusalem.

Although she has lived most of her life in the United States, Batya’s ties to Israel are strong, and her love for the country is untainted by Elie’s frustrations and hurts.

It was her destiny, she believes, that she met Elie Borowski at an archaeological exhibit at the Israel Museum. It was her destiny that led her to marry this tempestuous, brilliant, difficult, loving man 16 years older than she.

It is her destiny, she believes, to bring the Borowski collection where it belongs—to Jerusalem.

When the efforts to provide for the collection in Canada foundered, flagged, sputtered and then died, it was Batya who negotiated with Jerusalem’s mayor, Teddy Kollek, to have the collection permanently housed in Jerusalem.

In 1984, an agreement in principle was reached to bring the collection to Israel. “It has been a long road for us all,” Kollek wrote. In a letter to Borowski, Kollek spoke of “our mutual dream, the transfer of your remarkable collection to the only city in the world that can really complement it, Jerusalem.”

It may have been a long road, but the end is still far off.

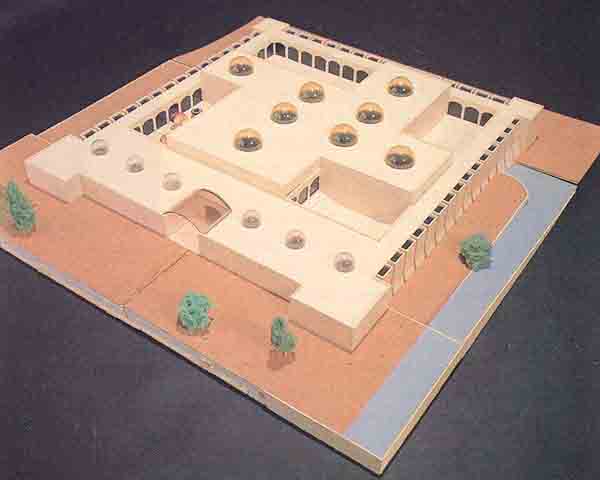

A formal request has been made to the Israel Land Authority for a construction site for a Lands of the Bible Museum. The new museum is planned for a beautiful plot on the other side of the road from the parking lot of 025the Israel Museum.d

But the rest is up to—Borowski!

So far the only contributor has been—Borowski!

He has commissioned an impressive model of the new museum, but where will the funds come from to build it and staff it, to pay its curators and fund the research projects that will make it a living institution?

I asked Borowski why he didn’t supply the funds himself, both to build the museum and to endow it.

His only source of funds is his collection. And he simply will not put on the private market objects that are not duplicated in any other collection and that are therefore irreplaceable at any price. To do so would be more than he can bear emotionally.

Besides, he asks, is it not enough if I give my collection? Shouldn’t others give now? The anger mounts visibly inside him: “If the world is not willing to give a home to this collection, the world does not deserve it.”

Why should it be so difficult to raise money for The Lands of the Bible Museum? One suggestion is that the collection is “caviar to the general.” It may be a collection more for the connoisseur than for the public.

In the words of a Canadian minister of culture, which finally prompted Borowski’s decision to take the collection to Jerusalem, “It does not have enough popular appeal.” That is why museum curators covet a few centimeters of a Picasso painting in preference to another ancient cylinder seal, regardless of its age, its cultural import or its unique characteristics.

In his heart of hearts, Borowski knows this. And it hurts. When he is looking at the pieces in his collection and discussing what can be seen in them and learned from them, he is boyish in his delight. His energy, when it comes to his collection, is inexhaustible. His love is endless. It hurts that the world does not share his enthusiasm.

Yet he knows that the world has changed. Neither the dealers nor the collectors are the same, he says. The traditions of culture and learning are dying. He estimates that no more than three people in the United States would be potential customers for the pieces in his collection.

Today even the curators, he says, are only administrators, serving not culture, tradition and learning, but the public taste.

He knows, too, that many modern curators regard the contents of his collection as plunder. To many, as it was to me, it is sickening to see a mosaic chiseled into chunks to make more pieces. It is sad to see an artifact, however beautiful, whose provenance is described as “somewhere in the eastern Mediterranean” or whose date cannot be fixed within a thousand years.

Yet, Borowski argues, it was the great dealers and collectors like himself, men and women of tradition, culture and learning, heirs of the Medici, who have preserved what we have. Without them, says Borowski, there would be no curators because the museums would be empty.

Today Borowski’s collection lies dormant—in a Toronto warehouse, in the storage rooms of the Royal Ontario Museum, and in the beautiful vitrines of his own home. Today Elie Borowski is still dreaming of “bringing the Bible alive.” He remains an optimistic dreamer. But at age 71, he is also a man of action. If anyone can realize his dream, it is he and Batya. Besides, there is no one else to do it.

Eliechish, his brothers called him. Elie the dreamer. He does not deny it; he is a dreamer. Today he is 71 years old and still dreaming. One of Elie Borowski’s dreams is 20 years old. Whether it will ever be realized is still an open question. He tries to suppress his anger and frustration, but it spills out all over. “Please, Elie, don’t say it,” his wife pleads. He cannot be stopped; he is a compulsive talker anyway. He has given so much; why shouldn’t others be willing to do even a tiny fraction of what he has done? […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

See Lawrence E. Stager and Samuel R. Wolff, “Child Sacrifice at Carthage—Religious Rite or Population Control?” BAR 10:01.

The Hildesheimer Seminary was named after its founder, Azriel Hildesheimer (1820–1899), a Jewish scholar who founded the Berlin Rabbinical Seminary in 1873 to promote neo-Orthodoxy and to counter the growing influence of Reform Judaism.