Ephesus: Key to a Vision in Revelation

024

025

A careful study of the archaeology of Ephesus will, I believe, deepen our understanding of one of the visions in the Revelation of John, perhaps the most difficult book of the New Testament.

The last book of the New Testament canon, Revelation records the fantastic heavenly revelations received by a certain John. Known as the Revelation of John or the Revelation to John, the book is also called the Apocalypse, which is simply the Greek word for revelation. The book begins, “The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants what must soon take place and he made it known by sending his angel to his servant John” (Revelation 1:1).

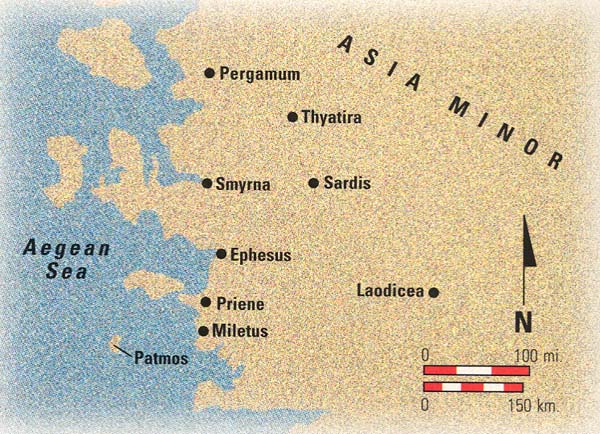

The so-called seven letters to the churches of Asia follow, the first of which is to the church at Ephesus. For this reason, some commentators suggest that the book was written in Ephesus, although John himself says only that at one time he was “on the island called Patmos” (Revelation 1:9). The other six letters were written to churches in Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia and Laodicea; all seven of these cities are in western Asia Minor and belonged to the Roman province of Asia in the first century C.E.

Despite the difficulties in understanding Revelation generally, most scholars agree that the book is intended to condemn the Roman empire, its leaders and its culture.1 The bestial, chaotic images apply to Rome. We will be focusing here on chapter 13, which is part of that pattern. In chapter 12, we are told of a dragon who fought a war in heaven against Michael and the angels. The dragon is defeated and thrown down to earth:

“And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him … Rejoice then, O heaven and you that dwell therein! But woe to you, O earth and sea, for the devil has come down to you in great wrath, because he knows that his time is short!” (Revelation 12:9, 12).

In chapter 13, a beast with seven heads rises out of the sea (Revelation 13:1), and the dragon of chapter 12 gives its power to this beast (Revelation 13:2). Then a second beast appears and exercises all the authority of the first beast (Revelation 13:11–12). A fuller description of this grisly pair of beasts is given in the sidebar “Revelation 13: The Vision of the Two Beasts.” The second beast “deceives those who dwell on earth” (Revelation 13:14). “[T]hose who will not worship the image of the beast [will] be slain” (Revelation 13:15). The beast causes all to be marked on the forehead (or the right 026hand) with his name or the number of his name,a 666, presumably to control them better (Revelation 13:16–18).

This may seem an unlikely passage for archaeology to illuminate. I hope to show not only that it can, but that it can do so in the way that archaeology illuminates best—not by identifying this or that fact, but by fostering (or gaining) a better understanding of the broad social conditions of the time.

Before we embark on this quest, we need to consider two other elements: First, the date Revelation appeared, and second, the generally agreed significance of the two beasts.

According to the second-century Christian writer Irenaeus, Revelation first appeared in Asia near the end of the Roman emperor Domitian’s reign, roughly 90–96 C.E. The majority of scholars have accepted this date.

Most scholars agree that the book is vehemently anti-Roman. There is even general agreement that chapter 13 is a sarcastic, visionary description of worship of the Roman emperors in western Asia Minor.2 The first beast—the beast from the sea—represents the authority of Rome. It is empowered by Satan, the source of all evil; thus Rome rules through deception and military power. The second beast—its local ally—comes from the land. This second beast does two things: it exercises Rome’s authority and it causes the people to worship Rome. Anyone who does not take part in this worship is subject to capital punishment. In short, the Book of Revelation is a stridently dissident depiction of a common institution in the Roman imperial world: the worship of emperors.

And this is where archaeology comes in. Archaeology can tell us a great deal about Roman emperor worship—especially at Ephesus; it can tell us what the author of Revelation was inveighing against and can thereby deepen our understanding of his vision.

During the Hellenistic period (third-second centuries B.C.E.), Pergamum, not Ephesus, served as the capital of western Asia Minor. It was ruled by an independent dynasty, the Attalis (283–133 B.C.E.). When Attalus III, the last ruler of this dynasty, died in 133, he bequeathed his realm to the Romans, who had once prevented the Seleucids to the east from taking the area.

In 31 B.C.E. Augustus (Octavian) routed Mark Antony in a naval battle at Actium, finally putting an end to the wars that had convulsed the eastern Mediterranean. A thorough restructuring of many Roman territories followed. Asia was reorganized, and Ephesus became the new governmental center of the province. Although Augustus left no record of why he chose Ephesus over Pergamum, the reasons are not difficult to appreciate. Pergamum was about 25 miles inland; Ephesus, on the other hand, was a port city with access to major sea and land routes. Another reason may have been that Pergamum was already so developed—with palaces, temples, fortifications and gymnasia left from the days when the city was the capital of an independent dynasty—that there was no room in the city center for the monumental building projects that characterized the early imperial period (c. 27 B.C.E.–100 C.E.). Ephesus, however, had plenty of room for development, and from the archaeological 027remains, we can learn a great deal about Roman emperor worship, the context of Revelation 13.

After Augustus’ victory at Actium, Ephesus experienced tremendous growth and was thus well positioned to reap the economic benefits of the Pax Romana of the early imperial period. There was no need to station Roman legions in the province, and the proconsulship of Asia became the fitting culmination of the most distinguished senatorial careers.

By the time Revelation was written in the late first century C.E., Ephesus was an established city of international importance and renown. Significant developments in the life of the city during the reign of Domitian (81–96 C.E.) provide a window onto the social setting of Revelation.

After a brief introduction to the city of Ephesus, I will focus specifically on two Ephesian monuments constructed in Domitian’s reign that reflect significant developments in imperial cults during the very period when, and in the very region where, Revelation was produced: the Temple of the Sebastoi and the bath-gymnasium complex near the harbor.

By Domitian’s time the city had already been well developed. The cult of Artemis had a venerable history. Modern scholars have traced its origins to the second millennium B.C.E. An earlier temple of Ephesian Artemis was rebuilt after a fire in the mid-fourth century B.C.E. In Domitian’s time the temple was a source of great civic pride and a major economic center.

From the Temple of Artemis, an ancient processional way made a loop around Mt. Pion, through the city and back to the temple. This processional way ran south along the eastern side of Mt. Pion to the gate at the upper end of the city. Inside the gate was the state agora, or gathering place, developed during the Augustan reorganization of the city. This agora was devoted especially to governmental buildings. Another, the Tetragonos Agora, near the harbor, was devoted mostly to economic activity. Other buildings in the state agora area were dedicated to the city’s publicly supported cults, such as the mysteries of Artemis. A double-cellab temple (founded about 29 B.C.E.) on the north side of the state agora was most likely dedicated to the cults of Rome and of the deified Julius Caesar.

As the ancient processional way led out of the state agora, it intersected the city’s main street, now called Curetes Street. Just south of this intersection lies the remains of the Temple of the Sebastoi. From the Temple of the Sebastoi, the processional way led down Curetes Street to the harbor area.

Curetes Street was lined on either side with wealthy residences and a variety of monuments and stores. Some large homes on the hillside south of the street have been excavated and are referred to as the Slope Houses. Across the street from the houses is a late first-century urban bathing establishment. Walking down the street, the modern visitor passes several monumental tombs, including the famous second-century library built over the last resting place of Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaianos, the first Asian to serve as the proconsul of his home province (106 C.E.).

Further on, the processional way skirts the Tetragonos Agora and passes by the Ephesian theater mentioned as the site of the riotous gathering in Acts 19:23–41031. A left turn onto Arkadian St. brings us to the second complex we will look at more closely, the bath-gymnasium complex in the harbor area.

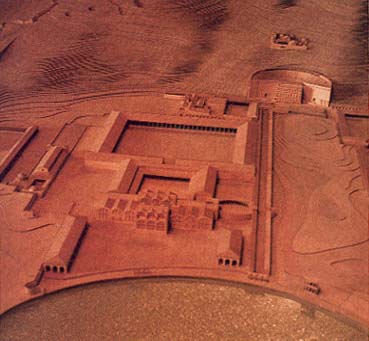

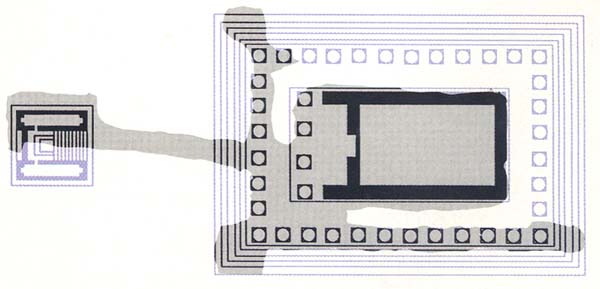

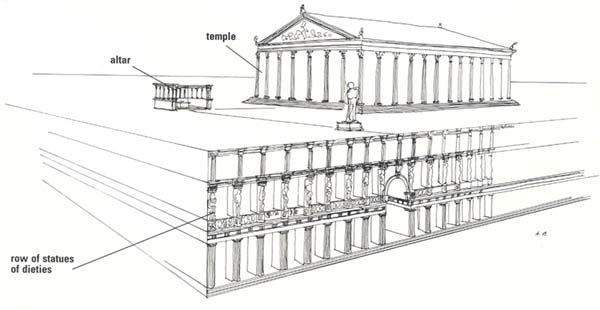

The Temple of the Sebastoi was built on an artificial platform that created a level space for the temple and its precinct. This artificial platform provided a precinct nearly 300 feet long and over 200 feet wide. On the north side of the platform, where the bedrock sloped down, was a three-story stoa which rose nearly 35 feet above the plaza at the base of the platform. The first-story colonnade of the stoa was executed in Doric half-columns. Behind this colonnade was a sheltered walkway in front of a series of shops. The second-story colonnade was ornamented with engaged figures of deities on each column, creating an array of gods and goddesses below the temple. The symbolism was powerful: The deities of the empire supported and protected the emperors who were worshiped in the temple above. Conversely, the emperors were the unifying element that brought the gods and goddesses together. In this sense, the emperors had become the focal point in the relationship between the human 032and divine realms.3

The temple was by no means grandiose. With internal measurements of 42 feet by nearly 25 feet, it would be considered a medium-size temple. The building itself was set near the middle of the precinct in the Greek style, rather than near the back wall according to Roman fashion. Only the foundations of the temple are left today, but they reveal that a specifically Asian design was chosen for the building, with four columns in front and a ring of columns around the outside.

In front of the temple was the altar on an axis with the temple. The altar was raised on a platform and enclosed within a U-shaped colonnade 30 feet on a side, with the open end toward the temple. These also were a common feature of Hellenistic temples in Asia. The Temple of Ephesian Artemis had a much larger version of this kind of altar platform, but the most famous example is the monumental Altar of Zeus and Athena in Pergamum.

Only one piece of sculpture has survived from the Temple of the Sebastoi—a statue of the emperor Titus (79–81 A.D.). In 1930 when the statue was found among the vaulted substructures of the temple platform, the excavators identified it as Domitian. More recent examination has shown, however, that the face is that of Titus, Domitian’s older brother and predecessor as emperor. The statue was not executed according to the official Roman portrait of Titus but rather in a more idealized style called “Asian baroque.”4

Another mistaken idea about the statue was that it stood outside the temple, overlooking the plaza below. True, a statue nearly 25 feet tall would certainly have made an impression on viewers below, but an examination of the statue itself shows that it must have stood indoors. The statue was akrolithic—that is, the body was made of wood and the extremities of stone. This kind of statue could not have been placed outside because the wooden parts would have quickly deteriorated in the rain. Moreover, the back of the head was not completely finished, and a large groove was carved there to reduce the weight of the stone. The statue could only have been displayed in front of a wall where visitors were not expected to go behind it. The statue of Titus must have been displayed inside the temple.

Up to this point, we have simply assumed the Temple of the Sebastoi was dedicated to the cult of the emperors. Now it is time to face the question directly: To whom was this temple dedicated?

Because of the statue, some scholars have suggested that the temple was devoted to the worship of Titus, although he reigned only two years. This is an important issue because it touches on the nature of the imperial cult and its significance for Asia in the late first century. Ultimately, it bears on the interpretation of Revelation 13.

That the temple was not devoted exclusively to Titus is shown by several inscriptions that unfortunately have been too often ignored. At least 13 of the inscriptions from Ephesus relate directly to this temple.5 The 13 inscriptions were commissioned by various cities in Asia for the opening of the temple. These inscriptions consistently refer to the temple as “The Temple of the Sebastoi.” Sebastoi (“revered” or “worthy of reverence”) is plural, the Greek translation of the Latin Augusti (singular Augustus). Since these inscriptions were official documents on public display, we have to conclude that the temple was dedicated to 033more than one emperor.

In determining which emperors were included in the cult, it will be helpful to bear in mind the following emperors and their dates: Nero (54–68 C.E.), Vespasian (19–79 C.E.), Titus (79–81 C.E.) and Domitian (81–96 C.E.).

Just to give a little background, Vespasian led the Roman armies that were called upon to suppress the First Jewish Revolt against Rome (66–70 C.E.). When Nero was assassinated, Vespasian returned to Rome before finishing the job with a final attack on Jerusalem—this he left to his son Titus. The famous Arch of Titus, depicting Roman soldiers carrying aloft the sacred relics from the destroyed Jewish temple, was erected in Rome to celebrate this victory. It is still one of Rome’s most popular tourist sites. Upon his death in 81 C.E., the Senate immediately deified Titus. He was succeeded by his younger brother Domitian, who reigned until he was assassinated in 96 C.E. Because Domitian alienated Rome’s elite during his rule, the Senate in Rome promptly denounced Domitian after his death, voted a damnatio memoriae and ordered that his name be removed from inscriptions throughout the empire.

Returning to the inscriptions commissioned by various cities in Asia, they originally began with a reference to the emperor Domitian, which means that they were executed during his reign. Later, in 96 C.E., the personal names of Domitian were carefully chiseled our of the inscriptions in accord with the decree of the Roman Senate. Most of the 13 inscriptions were then rededicated to Vespasian, who was called theos (god)

Since the reigning emperor was always included in the emperors’ cult, we can safely conclude that Domitian was a part of the original temple cult. The statue of Titus indicates that his older brother would also have been a part of the cult.

Even though two emperors is enough to explain the plural Sebastoi in the name of the temple, I would argue that at least one more person was included. It would have been unusual for the two brothers to have been venerated without their father, Vespasian, especially since Vespasian died an honorable death and was reasonably well thought of in the succeeding years. The rededication of the inscriptions to Vespasian supports this suggestion. Moreover, even after Domitian’s name was removed, the plural Sebastoi was still used. The name of the temple was not changed to the “Temple of Sebastos [singular],” even though Domitian was no longer included in the cult. The temple was thus originally dedicated to the cult at least of Domitian, Titus and Vespasian.

We can also easily exclude some emperors. Augustus and Tiberius (Augustus’s adopted son, who reigned from 14 to 37 C.E.) already had provincial cults; a second cult for them in Asia would have been superfluous so long after their deaths. Caligula (37–41 C.E.) and Nero were clearly unsuitable candidates for cultic honors because their reigns were so disastrous for the Roman aristocracy. Claudius (41–54), the only other emperor before Domitian, would not have been offered a cult nearly 30 years after his death.6

So the Temple of the Sebastoi was dedicated to a 034cult of the Flavian emperors Domitian, Titus and Vespasian. Since other members of the imperial family were often included in imperial cults, it is possible that Domitian’s wife, Domitia, and Titus’ daughter, Julia, may also have been so honored; they both appear on Ephesian coins at this time.

What can all this tell us about Revelation 13? It provides background material on the imperial cult that is the subject of John’s denunciation. It indicates that the subject of the denunciation is not, as some commentators have suggested, Domitian alone. The usual background given for this chapter is that John was inveighing against Domitian because of his persecution of the church and because he ordered his subjects to give him divine honors. Recent research has shown that Domitian’s persecution was episodic and not significantly different from other emperors in the late first and early second centuries. Indeed, the image of Domitian as despotic and blasphemous is now an outdated evaluation. More important for our purposes here, however, is that confining the subject of John’s condemnation to Domitian alone—supposedly a single, perverse emperor—misses the profundity of John’s political theology. Imperial cults were not an aberration of Domitian’s reign. The worship of the emperor was in fact a characteristic feature of Greco-Roman life. John was not criticizing a particular emperor; he was denouncing the cultic system that provided the backbone of the social order.7

One other item is important: The temple is identified in the inscriptions as a provincial temple; it was not built as a municipal or individual project. This means it was established by the provincial council of Asia (the koinon) after approval by the Senate in Rome. That is why the other cities of the province set up inscriptions when the temple was dedicated in Ephesus. The cities would also have sent delegations to the dedication ceremonies, and may even have helped finance the project. Thus the Temple of the Sebastoi in Ephesus provides us with information about socio-religious developments in the late first century in the province of Asia as a whole, not just in the city of Ephesus. In short, in the 80s wealthy families from various cities and towns in Asia made a cooperative effort to honor the Flavian imperial family with a temple and cult dedicated to them. They were able to gain approval from Rome for this provincial cult even though the province of Asia already had two provincial cults—one in Pergamum for Augustus and for Rome, founded in 29 B.C.E.; and, one in Smyrna for Tiberius, Livia and the Senate, founded in 26 C.E. This was a remarkable achievement. No other province is known to have had more than one provincial cult of the emperors at this time, and several provinces appear to have had none. Clearly, Asia was on the cutting edge of imperial cult activity. And John was denouncing the entire institution as coming from the devil.

The bath-gymnasium complex in the harbor area, to which we now turn, was the largest building project of the Domitianic period. My research suggests that this complex was built by the Ephesians in honor of Domitian at about the same time the province built the Temple of the Sebastoi for Domitian’s family. Most bath-gymnasia in Asia at this time integrated two elements: a Roman-style bath building and a palaestra (a square complex with rooms that open to an inner courtyard and used for athletic purposes, lectures and occasionally for cultic sacrifice). Bath-gymnasia complexes, not only in Ephesus but also in Priene and Miletus, tend to form a rectangular complex. They are also smaller. The Ephesian complex, however, was unique in that it consisted of three adjoining elements: a bath building with bathing facilities near the harbor; a palaestra with rooms surrounding a courtyard; and a gymnasium with an extremely large courtyard completely enclosed by stoas. The entire complex was immense—nearly 1,200 feet long. The widest element was the gymnasium, at nearly 800 feet.

The inclusion of the gymnasium was important not only for its size. It represented a specifically Greek style of urban life, emphasizing both mental and physical exercise. Here athletes trained and philosophers 036taught. More important for our interest, the complex appears to have been built to honor Domitian as Zeus Olympios with his own “Olympic” festival.

We know that the Ephesians established their own games in the Domitianic period from an inscription found on the island of Iasos that commemorates the victory of Metrobius at the Ephesian Olympics in about 90 C.E.8 Although the Ephesians had established their festival in honor of Domitian, they had to discontinue the games when he was assassinated.9 They were reinstituted, however, about 30 years later, this time in honor of Hadrian as Zeus Olympios.

The unusual combination of bathing facilities, palaestra and gymnasium was apparently modeled on analogous facilities at Olympia itself, the home of the venerable Panhellenic Olympic games. Olympia provides the only comparable conjunction of palaestra and gymnasium in the late first century C.E. The Ephesians took this general plan, made it rectilinear in accordance with early imperial urban planning, and drew the bathing facilities directly into the plan—another Roman-period fashion.

Thus while Asia expressed its reverence for the Flavian emperors by constructing a temple for the cult of the emperors in Ephesus, the Temple of the Sebastoi, the Ephesians established an Olympic festival in Domitian’s honor. To do this, they created a monumental platform for the temple in the upper city area and remodeled a large Section of the city’s harbor area along the lines of the Panhellenic facilities at Olympia. Even though their Olympic festival had to be cancelled on Domitian’s untimely death, the facilities continued to function on a daily basis as an important urban institution.

Together the Temple of the Sebastoi and the bath-gymnasium complex near the harbor reflect significant trends in late first-century Ephesus. The worship of the emperors altered two major areas of the city—the intersection of Curetes St. and the state agora with its new temple; and the harbor area with its new bath-gymnasium complex. Equally important, the worship of the emperors gave a new coherence to the city by creating a link between these two areas. The imperial cult in effect provided a fresh unity to the entire city. In its own way, Asia was integrating its contemporary social realities through reverence for Roman authority, and that reverence was expressed in the vocabulary of the region’s local religious traditions of sculpture, sacred architecture and festivals.

It is important to understand that these changes were to be found not only in Ephesus. These same processes were at work throughout the province at various levels. The whole province was involved to some extent in the construction of the Temple of the Sebastoi. Later, in the second century, similar cults proliferated throughout the province. Ephesus is 037simply the place where these developments in emperor worship are most in evidence, partly because of the leading role Ephesus played in the province, but also because Ephesus has been extensively excavated—indeed, it is the most extensively excavated city in the region.

Revelation presents a dramatic critique of this situation. John’s vision declared that Rome—the beast from the sea—was not ruled by divine emperors. Its authority came from Satan. Roman rule was simply smoke and mirrors—deception enforced by its known ability to wage war.

The local aristocracy—the beast from the land—led the way in veneration of the emperors. Increasingly urban life in Asia was organized around emperor worship. The benefactions of this aristocracy built temples and monuments, its patronage paid sculptors and its support provided the inscriptions that publicly extolled the Roman order. In this way the elite mediated the authority of Rome.

John’s vision excoriated this system. It declared invalid the increasingly successful social contract of late first-century Asia. That contract, according to Revelation, was based on blasphemy, maintained by violence and dedicated to the destruction of those who sought to live a godly life. To those of like mind, John’s visions were prophetic. To most of the inhabitants of Asia, however, they would have seemed like sedition.

A careful study of the archaeology of Ephesus will, I believe, deepen our understanding of one of the visions in the Revelation of John, perhaps the most difficult book of the New Testament. The last book of the New Testament canon, Revelation records the fantastic heavenly revelations received by a certain John. Known as the Revelation of John or the Revelation to John, the book is also called the Apocalypse, which is simply the Greek word for revelation. The book begins, “The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants what must soon […]

You have already read your free article for this month. Please join the BAS Library or become an All Access member of BAS to gain full access to this article and so much more.

Already a library member? Log in here.

Institution user? Log in with your IP address or Username

Footnotes

Hebrew and Greek letters have numerical values; thus the numbering of the beast (666) is the sum of the letters of his name.

Endnotes

An important, recent exception to this position is Leonard L. Thompson, The Book of Revelation: Apocalypse and Empire (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990).

See, for example, Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, Revelation: Vision of a Just World (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1991), pp. 82–87 and 117–139.

In Rituals and Power The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor (Cambridge: Cambridge, UK Univ. Press, 1984), p. 233. Simon Price described the emperors as the focal point between human and divine, but the exact meaning of the phrase in that context is not completely clear to me. I use the same phrase here, and try to articulate the meaning as I understand the evidence.

Max Wegner in George Daltrop, Ulrich Hausmann and Max Wegner, Die Flavier Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Nerva, Julia Tit, Domitilla, Domitia (Berlin: Mann, 1966), pp. 26, 38, 86. See also Jale Inana and Elisabeth Rosenbaum, Roman and Early Byzantine Portrait Sculpture in Asia Minor (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1966), p. 67.

Hermann Vetters, et al. (Bonn, Germany: Rudolf Habelt, 1979–1984), IvE (Die Inschriften von Ephesos) 2.232–242; 5.1498; 6.2048.

The inscriptions also enable us to date the Temple of the Sebastoi more precisely than the fifteen-year Domitian reign. The two formulas used in the 13 inscriptions include the name of the then-current Roman proconsul of the province, as well as other officials. The three proconsuls named in the inscriptions served between 88 and 91 C.E. and, starting in 89/90, a prominent administrator of the temple (the neokoros) is also named. Since these inscriptions were commissioned for the dedication of the Temple of the Sebastoi, we can conclude that the cult became functional between 88 and 91, most likely in the year 89/90. The documentation of the argument for the dating can be found in chapter 2 of my study Twice Neakoros: Ephesus, Asia, and the Cult of the Flavian Imperial Family (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming 1993).