“Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised on the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.” So said God to Abraham, establishing the covenant of circumcision, a covenant “between me and you and your descendants after you” (Genesis 17:10, 14).

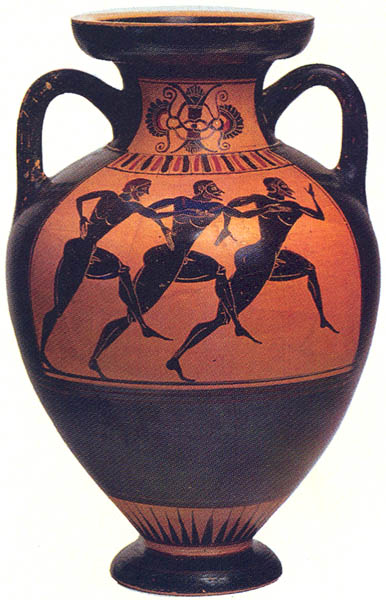

For centuries, Jewish boys have regularly been circumcised when they are eight days old (Genesis 17:12). An unusual challenge to circumcision developed, however, in the Hellenistic period (after about 133 B.C.E.a). Hellenistic and Roman societies widely practiced public nakedness. But they abhorred baring the tip of the penis, called the glans. To expose the glans was considered vulgarly humorous, indecent or both. This combination of attitudes could be—and often was—devastating for circumcised Jews. Enjoying oneself in a Greek gymnasium or Roman bath, where nudity was de rigueur, was a popular and stylish pastime. Here politics was discussed and business deals concluded. Athletic contests and exhibitions were also conducted in the nude. Participation in athletics was often a prerequisite for social advancement. Yet a circumcised penis effectively precluded this participation.

Consequently, for hundreds of years some Jews underwent a surgical procedure known as epispasm—an operation that “corrected” a circumcised penis. Some might call it circumcision in reverse. From references and allusions to the procedure in classical and rabbinic literature, it appears that epispasm reached the peak of its popularity in the first century C.E.

The New Testament reveals bitter conflicts over circumcision among the followers of Jesus, conflicts expressed also in attitudes toward epispasm practiced by Jews. Paul, who thinks circumcision useless, nevertheless forbids epispasm: “Was any one at the time of his call already circumcised? Let him not seek to remove the marks of circumcision,” he advises the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 7:18).

Numerous written sources from the second century B.C.E. to the early sixth century C.E. speak about epispasm and attitudes toward it.

During these centuries, foreskins assumed an importance they have rarely had before or since. The Roman emperor Hadrian (117–138 C.E) loathed circumcision as much as castration—both were unnatural, an offense against the Greek idea of the natural beauty of the human body—and outlawed both.1

Males who wished to conceal an exposed glans had several options. Dioscorides, a first-century C.E. physician to Nero’s troops and master of herbal lore, helped those who, though not circumcised, had a defectively short foreskin. He suggested applying thapsia, an herb that causes swelling.2 This would not work, Dioscorides recognized, for those who were circumcised.

Soranus, author of a second-century C.E. medical text prescribed a different method for correcting defectively short foreskins in infants: The baby’s nurse should pull the foreskin over the glans and tie it with thread. “For if gradually stretched and continuously drawn forward, it easily stretches and assumes its normal length and covers the glans and becomes accustomed to keep the natural good shape.”3

A simple surgical procedure, called infibulation, was another option for a defectively short foreskin. A surgeon would pierce the foreskin to receive a light wooden pin called a fibula.4 With the fibula inserted the foreskin was held neatly closed. Infibulation purported to improve the voice and health of adolescent boys, but Celsus, the author of a medical text from the first century C.E., doubts the therapeutic value of infibulation for this purpose.

Infibulation could also be used by those who had been circumcised. Some circumcised Jews concealed their circumcision by drawing the skin around the penis forward and securing it with a fibula—or with twine. Martial, the Roman poet, ridiculed an infibulated Jewish slave5 and derided another Jew whose fibula fell out at the bath.6

The Cadillac of correctives, however, was clearly epispasm: “If the glans is bare and the man wishes for the look of the thing to have it covered, that can be done,” Celsus assured his readers.7 It was a variation of an operation recommended for congenitally short foreskins. For congenitally short foreskins, the surgeon would tie forward the foreskin, as Soranus recommended, and cut the sheath of skin around the penis just in front of the pubic bone. When the wound healed, the surgeon would remove the twine.

Epispasm on a circumcised penis required a somewhat more difficult operation: The surgeon would cut around the glans freeing the sheath of skin surrounding the shaft of the penis, pull the skin forward and dress the wound carefully so that the skin would reattach to the glans, leaving a foreskin. At a time before any effective anesthesia, a man inclined to try this surgical procedure nevertheless had Celsus’s assurance that it was “not so very painful.”8

Epiphanius, the fourth-century C.E. churchman, tells of a man who was circumcised twice, once as a Samaritan and again as a Jewish proselyte. In the course of the discussion, Epiphanius mentions a spouthisteros, a special implement for performing epispasm. He tells us, “If you can make circumcision uncircumcision, do not marvel at some being circumcised twice.”9

Some Jews probably submitted to epispasm because they shared the common Greek and Roman revulsion toward circumcision. Even if they did not, however, societal institutions and attitudes exerted strong pressure against remaining circumcised. Jews of means naturally wished to participate in gymnasium and bath. Not only were these a chief means of recreation, they also functioned as hubs for business. If Jews exercised or bathed while circumcised, they offended their gentile neighbors and submitted themselves to incredulous ridicule; if they did not attend, everyone knew why—and talked about it. Either way their business would suffer.

Other factors also encouraged epispasm.

Athletics constituted a chief avenue of social advancement for underclass boys. Greek cities competed with each other to grant citizenship to promising boys and to sponsor them at the games. Since athletes exercised and competed without clothes, this avenue was denied to those who were circumcised. What city would sponsor an obscenity?

After the Jewish revolt against Rome in 66–70 C.E., punitive measures against Jews were more easily enforced against those who could be identified because they were circumcised. Suetonius tells of an old man claiming exemption from the most hated of these measures, a two drachma tax to fund the worship of Jupiter. The judge stripped the old man in court, found him to be circumcised, and fined him.10 A Jewish man could escape such oppressive measures and the stigma attached to them by submitting to epispasm.

Obstacles to citizenship in Greek cities like Alexandria also encouraged Jews to undergo epispasm.11 In Alexandria and perhaps in other cities formed on the Greek model, citizenship and the important privileges that went with it were granted only to ephebes, those trained for citizenship in the ephebaion. Since local law forbade Jews from becoming citizens and since ephebes regularly exercised naked in the gymnasium, a Jew who appeared naked with a circumcised penis was unable to circumvent the law. Some Jews did evade the law, however; a Greek delegation from Alexandria complained about this to the emperor.12

Greek and Roman abhorrence of circumcision produced a variety of predictable reactions among Jews. Those who stood vigorously against Greek culture asserted the necessity of circumcision in stronger terms than ever. The Jewish author of Jubilees interpreted Greek culture as the product of the demonic world; circumcision, he tells us, lifts Jews out of the evil realm and places them directly under God’s rule.13

Other Jews who accepted Greek culture attempted to explain circumcision to the Greeks and to themselves. A certain Jew named Artapanos (third to second centuries B.C.E.) took a novel approach: Moses founded the religion of Egypt and gave circumcision to Ethiopia.14 If Egyptians and Ethiopians in following their ancestral practices still keep the teachings Moses, why should Hebrews not keep them as well?

The first-century C.E. Jewish philosopher Philo defends circumcision in Greek terms by listing physical and allegorical advantages. Circumcised men are more fertile, less vulnerable to disease and, being cleaner, are more fittingly set apart as a nation of priests. In addition, the heart begets the thought, which is the highest human excellence; therefore penises should be circumcised to resemble the godly heart. Moreover, circumcision represents the excision of the pleasure of sex, which bewitches the mind.15

Some Jews, faced with overwhelming societal repugnance toward circumcision, probably neglected it. Many of these Jews simply ceased to practice Judaism at all and quietly faded into the surrounding culture. Others neglected circumcision but actively claimed their Jewish heritage. The evidence for uncircumcised yet practicing Jews is indirect but unequivocal.

For example, Ananius, after successfully convincing Izates, prince of Adiabene, to become a Jew, argued that he should not become circumcised.16 The Jewish author of the Fourth Sibylline Oracle urged gentiles to repent and immerse themselves in water but found no need to mention circumcision. Rabbis debated whether circumcision or immersion in water really made a proselyte.17 Philo tells us that the real proselyte circumcises not his foreskin but his passions.18 Such statements are readily explained if some authorities were contending that a person could be or become a Jew without being circumcised.

Philo rebuked Jews who allegorize the law to, abolish Sabbaths, feasts, the Temple and circumcision.19 These Jews interpreted the Torah to justify their neglect of circumcision, which suggests that in their own eyes they remained observant Jews.

Both confirming that many Jews neglected circumcision and affirming the rabbinic commitment to it, the Talmud tells us that Jerusalem fell to the Romans and the Temple was destroyed because Jews “broke the covenant by failing to circumcise their sons.”20

Some Jews practiced a form of circumcision that did not show. The reaction can be seen in the Mishnah’sb requirement that valid circumcision must bare the glans.21 The need for this ruling implies that some Jews practiced a form of circumcision—perhaps by simply nicking the foreskin—in a way that did not bare the glans. Removing only a little of the foreskin might obviate the need either for infibulation or epispasm. Jews who circumcised in this manner did not set out to abrogate the covenant of circumcision; they merely tried to keep the covenant without offending their gentile neighbors by baring the glans.

That epispasm was fairly widespread among Jews also seems evident from 1 Maccabees 1:11–15, where we are told that some built a gymnasium in Jerusalem and “made themselves uncircumcised.”

As might be expected, the rabbinic references to epispasm condemn it (while at the same time reflecting that it must have been a fairly widespread phenomenon).

In Pirkei Avotc 3.16, we are told: “The one who voids the covenant of Abraham has no portion in the world to come.”

According to the Talmud,d even Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, cannot eliminate the transgression of epispasm.22

In various midrashime several notorious biblical sinners, such as Jehoiakim,23 Achan24 and Adam,25 are said to have submitted to epispasm. As late as the 12th century, the Rambam (Moses Maimonides) stated that “anyone who elongates his foreskin [to conceal his circumcision]” is denied a share in the world to come.26

On the other hand, some talmudic rabbis are less harsh. They consider whether one who has undergone epispasm (a mashuk) should be recircumcised when rejoining the rabbinic fold:

“Rabbi Judah says, ‘One who has his prepuce drawn forward [i.e., who has submitted to epispasm] should not be recircumcised because it is dangerous.’ They said to him, ‘Many were circumcised [after epispasm] in the time of Ben Koziba and they had children and did not die.’”27

The reference to epispasm cited here date from the second century B.C.E. to early in the sixth century C.E. As we have seen, however, epispasm was only one reaction to the Greco-Roman abhorrence of circumcision. Some Jews who rejected Greek culture heightened the religious and social importance of circumcision: Circumcision delivered one from evil. Others, like Philo, impressed by Greek philosophy, used arguments consonant with Greek presuppositions to support the practice of circumcision. Still others thought their religious obligation was fulfilled if only a minute part of the foreskin was removed. Those who interpreted the Torah by Greek methods and sensitivities, argued that the law, when properly understood, did not require literal circumcision. Such a wide spectrum of views allowed plenty of room for Jewish men to practice epispasm while still living as Jews. Many of these men never thought they had violated the covenant. They only wanted to live in both worlds. They had received circumcision; the second operation only made their circumcision less conspicuous.28

Readers of BR will remember how central the debates over circumcision were to the development of early Christianity.f Since the early church was part of the Jewish community, the Christian debate can be seen as part of the Jewish discussion about circumcision. Like the Jewish community at large, the church was divided between those who required circumcision and those who did not. Many Christians despised the arguments of those who in their view sought to gain the approval of their gentile neighbors by neglecting the covenant of Abraham. If circumcision defines the sphere where God acts on behalf of his people and uncircumcision defines the sphere of demonic control, then Jesus must act among the circumcised; circumcision is required.

When Paul in Galatians (6:15) claims that circumcision is irrelevant or when Luke asserts that gentiles entering the people of God need not circumcise themselves (Acts 15:19–29), they enter a debate that has already solidified. All the arguments have already been made and answered; the two sides glower at one another across an unbridgeable gulf. Merely repeating well-known arguments would hardly convince anyone. Paul and Luke can persuade only by transcending the former arguments; they can obtain a hearing only from the party whose arguments they adopt.

Paul enters the fray accepting the arguments of the circumcision party. Paul agrees that the world has been divided into two spheres, the sphere of the circumcised where God has acted, and the sphere of the uncircumcised “gentile sinners” where demons rule (cf. Galatians 2:15). But for Paul the world where this distinction rightly applies is passing away: “[Christ] gave himself for our sins to deliver us from this present evil world according to the will of God the Father” (Galatians 1:3–4). Distinctions between circumcised and uncircumcised, proper to the old world, do not apply in the new. Since in Christ Christians are leaving the old world, circumcision has no relevance for them: “But far be it from me to glory except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me and I to the world. For neither circumcision counts for anything nor uncircumcision, but a new creation” (Galatians 6:14–15).

Luke also begins by accepting circumcision: he carefully depicts the circumcision of both John the Baptist and Jesus (Luke 1:59, 2:21). But after the resurrection Jesus reveals a new plan of God to a very puzzled group of disciples (Luke 24:36–49), a new plan that, includes gentiles (Luke 24:47). In Acts, Luke works out the consequences of this plan and chronicles the revelation to the disciples that under the new plan gentiles do not require circumcision (chapter 15).

By accepting as valid the arguments of the circumcision party, Paul and Luke could hope that their argument would be heard. By tying their conclusion that circumcision is no longer necessary to the new thing Christ has done, they could hope that they might convince Christians of the circumcision party who, of course, agreed that God had done something new in sending the Messiah. By denying the necessity of circumcision they could expect to attract gentiles to belief in Jesus. How well Paul, Luke and others like them succeeded appears from the result: Eventually the Church abandoned circumcision. The ancestors of modern Judaism did not; the wide variety of Jewish views on circumcision evidently died with the Hellenistic civilization that gave them birth, and Jews returned to the almost universal practice of the ritual of circumcision.

All Talmud citations are from the Babylonian Talmud.

MLA Citation

Footnotes

B.C.E. (Before the Common Era) and C.E. (Common Era), used by this author, are the alternate designations corresponding to B.C. and A.D. often used in scholarly literature.

See Jack T. Sanders, “Circumcision of Gentile Converts—The Root of Hostility,” BR 07:01.

Endnotes

See E. Mary Smallwood, The Jews under Roman Rule from Pompey to Diocletian (Leiden: Brill, 1976), p. 429.

Gynecology 2.34, in Soranus, Gynecology, transl. by O. Temkin (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1956), p. 107.

Celsus, De Medicina 7.25.1, W.G. Spenser’s translation, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press/London: Heinemann, 1938).

Celsus, De Medicina 7.25.1, W.G. Spenser’s translation, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press/London: Heinemann, 1938), p. 421.

See Maccabees 2:30–31, 3:21, 7:10–15. See also Victor A. Tcherikover, Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1959), pp. 311, 313.

Claudius, “Letter to Alexandria,” in Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum, ed. Tcherikover and A. Fuks (1957–1964), p. 153.

Jubilees 15:25–34. Similar ideas underlie the metaphorical use of circumcision at Qumran (CD 16.4–6; 1QS 5.5) and perhaps a traditional Jewish blessing used at circumcision (Shabbat 137b and parallels). So David Flusser and Shmuel Safrai, “Who Sanctified the Beloved in the Womb?” Immanuel 11 (1980), pp. 46–55.

Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica 9.27.4, 10; J.J. Collins, “Artapanus,” The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. by J.H. Charlesworth (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985), vol. 2, pp. 896–899.

Tosefta Shabbat 15.9, transl. by Jacob Neusner, in The Tosefta: Moed (New York: Ktav, 1981), p. 59; see also Yevamot 72a.